Diving Safety

Everything You wanted To Know About PFOs and Decompression Illness, But Were Too Busy Decompressing to Ask

Though your chances of getting bent are relatively low, your risk increases five to 13-fold in the presence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO), which may enlarge and become problematic with age. Skin bends anyone? Here cardiologist and rebreather instructor Doug Ebersole explains the latest research, whether you should be tested, and what it may mean for your diving.

by Doug Ebersole M.D.

Header image courtesy of Virginie Papadopoulou. Remaining images courtesy of Doug Ebersole.

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is an important topic in diving as the appreciation of its relationship to decompression illness (DCI) grows within the community. More than 1200 scuba divers from around the world are affected each year by DCI. Although the incidence of DCI is relatively low, ranging from about 1 episode per 10,000 dives (0.01% per dive) to about 10 episodes per 10,000 dives (0.1% per dive), depending on the nature of the dive, the presence of a PFO is felt to increase the risk five to 13-fold (1, 2, 3). As a result, an understanding of the link between PFO and DCI, as well as various treatment options, is vitally important to divers, and the health professionals who treat them.

Incidence and Anatomy

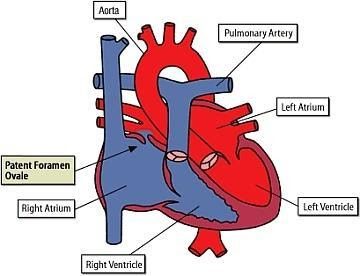

A PFO is an integral part of the normal fetal circulation. Normally, a portion of the blood from the inferior vena cava passes from the right atrium to the left atrium through the PFO during fetal life, bypassing the lungs. At birth, pulmonary blood flow increases greatly, increasing left atrial pressure. The resulting atrial pressure differences compress the septum primum against the septum secundum, functionally closing the PFO. Anatomic closure of the PFO occurs later in infancy in most people but is incomplete in approximately 25% of the population (4, 5), leaving these individuals at risk for right to left shunting.

PFO diameters are quite variable in size ranging from 1-19 mm/0.04-0.75 in, with the average size being larger in older adults (4), suggesting PFOs may continue to enlarge during life. The cause of this is unknown, but in part may be due to known elevations in right heart pressures with aging causing the pressure difference between the left atrium and right atrium (which keeps the PFO closed) to lessen. This may result in “larger” PFOs in older adults.

The Relationship of PFO to DCI

In 1986, it was first suggested by Wilmhurst and colleagues that a cardiac right to left shunt may be important for a paradoxical gas embolism in scuba divers (6). Subsequently, the importance of PFO for DCI in divers has been further investigated (1,7, 8, 9). As mentioned above, the risk of DCI in sport divers is quite low but is increased by at least five-fold in the presence of a PFO (1, 2, 3). Additionally, the average number of ischemic brain lesions as seen on MRI in experienced divers with PFO has been reported to be twice as high as in divers without PFO (11). The etiology and clinical significance of these findings are unclear but may represent multiple subclinical paradoxical embolic events across the PFO.

The Diagnosis

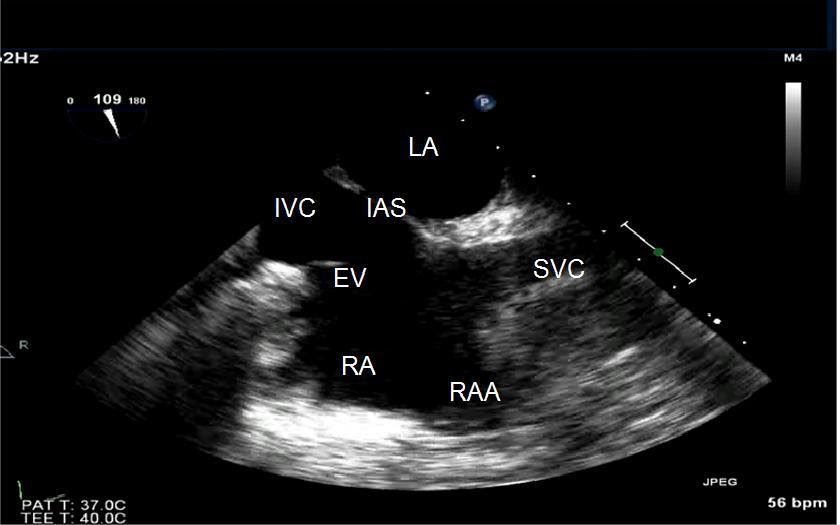

Both transthoracic echo (TTE), a cardiac ultrasound performed from the chest wall, and transesophageal echo (TEE), a cardiac ultrasound performed from the esophagus, have been used for the diagnosis and assessment of PFO. TTE is considered the preferred diagnostic test of choice as it is noninvasive. However, given its better visualization of the atrial septum, TEE, while more invasive, is much more accurate than TTE and can be used if, despite a negative TTE, there is still a high index of suspicion that the patient has a PFO.

Including a “bubble study” with the echocardiogram, either TTE or TEE, will increase the likelihood of diagnosing a PFO if it is present. This is done by connecting two syringes of saline with a small amount of air with a stopcock and then “swishing” the two syringes back and forth to “agitate” the saline, making small “microbubbles” that will be seen on ultrasound imaging. Visualization of microbubbles passing from the right to left atrium through the visualized foramen ovale is diagnostic of a PFO. In clinical practice, the actual site of right-to-left shunting may not be convincingly visualized or recorded for technical reasons. If the echo demonstrates microbubbles appearing in the left atrium immediately after arriving in the right atrium, then the presence of a PFO can be presumed. If bubbles appear in the left atrium more than five beats after they appear in the right atrium, then the possibility of shunting from another cardiac source (such as an anomalous pulmonary vein) or from a pulmonary source (such as a pulmonary arteriovenous malformations) must be considered.

Of note, while the injection of “agitated saline” is routinely done via an arm vein due to convenience, it has been shown that using a femoral vein in the leg is more accurate (12-13).

Therapeutic Options

No specific guidelines exist for PFO closure in people who have decompression illness, but the options are to stop scuba diving, decrease the depth and/or time of dives to limit the inert gas load, or undergo percutaneous PFO closure. Some divers decide that they have many other interests and diving is not that important to them. These divers will frequently give up the sport.

Other divers who enjoy the sport but dive infrequently often opt for diving “conservatively” to limit their bubble-load. This might involve no-decompression diving, limiting depths to less than 30m/100ft, diving nitrox on air profiles, making prolonged safety stops (greater than the recommended 3-5 min) at approximately 4-6m/15-20 ft at the end of their dives, and limiting the number of dives per day to one or two. Tech divers could also opt to dive more conservatively depending on their risk tolerance.

People who make their living through scuba diving—instructors and divemasters, for example—and tech divers who enjoy more aggressive types of diving such as deep wrecks, cave diving, rebreather diving, and mixed gas diving often elect percutaneous closure of the PFO. This also holds true for divers who have had recurrent “unexpected” DCI events despite diving conservatively as defined above.

The types of decompression illness that appear to be associated with PFO include cerebral (stroke-like symptoms), spinal (paralysis or urinary retention), cutaneous (skin bends), and inner ear (vertigo). DCI manifested by joint pain is felt NOT to be associated and, therefore, should not prompt evaluation for PFO.

Treatment Results

A recent study reported the results of conservative diving practices after an episode of DCI (14). Eighteen divers in this study had a right-to-left shunt, nine were small and nine were large. Mean follow-up was 5.3 years (range 0-11 years). Four of these divers had undergone PFO closure and had no episodes of DCI in follow-up. The absolute risk of suffering DCI before examination for the remaining 14 divers with right-to-left shunt and no closure was 23.5 DCI events per 10,000 dives for those with a small shunt compared to 71.6 events/10,000 for those with a large shunt.

After following the recommendations for conservative diving practices, the DCI risk at follow-up fell to 6.0 per 10,000 dives in the small shunt group and zero in divers with the large shunt. The major limitation to this study is its small sample size, but the results suggest a need for more studies of conservative diving practices for divers with right to left shunts.

When DCI has occurred, especially after so called “undeserved” cases of DCI, divers are often encouraged to seek screening for a shunt and some diving medical societies classify these divers as ineligible to return to diving (15). There are also several diving medical specialists who recommend that divers with a history of DCI and a positive right-to-left shunt, undergo closure if it turned out to be a PFO, even though there is no clear evidence to indicate that this intervention reduces the risk of DCI or neurologic events (16-19).

However, in a 2011 study of 83 scuba divers with a history of DCI and a follow-up of 5.3 years, 28 divers had no PFO, 25 had a PFO closure, and 30 continued diving with a PFO without closure (20). At the beginning of the study, there were no significant differences between the groups in the number of dives, dive profiles, diving depth, or cumulative dives to more than 40 meters of salt water (msw).

After follow-up, while there were no differences between the groups with respect to minor DCI events, the risk for major DCI was significantly higher in the divers with PFO and no closure than in divers with PFO and closure or divers without PFO. Although this offers new evidence that PFO closure reduces the risk for major DCI, the authors do not recommend closure in all divers with a history of DCI but rather recommend further studies to confirm these results.

A recent Divers Alert Network (DAN) funded study from our institution (21) also suggested selected divers with recurrent decompression illness may benefit from PFO closure. Seventy-seven patients with recurrent decompression illness and documented patent foramen ovale were enrolled. Please note this was not a randomized trial. Patients themselves decided whether to have PFO closure or to dive conservatively after the PFO diagnosis was made. This obviously imparts some bias into the trial. Fifteen patients were excluded for various reasons, leaving 62 patients who were followed prospectively for 5-6 years.

The baseline demographics which included age, gender, years diving, total number of dives, and number of dives per year were very similar in the two groups as was the number of divers who stopped diving or dived less after suffering decompression illness. A greater proportion of divers in the “PFO Closure” group had “large” PFOs. The follow up in the PFO closure group was six years and in the Conservative group was 5.5 years.

The 42 subjects in the PFO closure group had an incidence of decompression illness of 12.9 episodes per 10,000 dives prior to PFO closure and then had a statistically significant (p<0.05) reduction to 2.7 episodes per 10,000 dives after PFO closure. The 20 participants in the Conservative group had an incidence of decompression illness of 13.4 episodes per 10,000 dives. After 5.5 years of diving conservatively without PFO closure, the incidence of decompression sickness was 3.4 episodes per 10,000 dives, but this did not meet statistical significance given the small number of subjects.

Percutaneous PFO Closure

The closure procedure for a patent foramen ovale is relatively painless and is done nonsurgically using a needle stick into a femoral vein. Imaging during the procedure is done with a combination of fluoroscopy and ultrasound imaging, either TEE or intracardiac echo. The most common device in use in the United States is the Amplatzer PFO Occluder [see photo above]. This is a wire mesh made out of nickel and a titanium alloy. The device is filled with securely sewn polyester fabric to help close the defect. It is deployed through a small catheter which has been placed across the PFO. The procedure takes about an hour and patients are usually discharged home the same day or the following morning.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS), the United Kingdom Sports Diving Medical Committee (UKSDMC), and the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS) have all weighed in with formal recommendations on patent foramen ovale and decompression illness. Their recommendations are:

- A routine screening for PFO at time of dive medical fitness assessment is not necessary

- Consideration of investigating for PFO should be for divers with:

- History of DCI with cerebral, spinal, cutaneous or inner ear symptoms

- Current or past history of migraine with aura

- History of cryptogenic stroke

- History of PFO or ASD in first-degree relative

- If screening is performed:

- It should be performed in centers well practiced in the procedure

- Transthoracic echo (TTE) with agitated saline is the preferred first test

- Provocative maneuvers (Valsalva, sniff) should be performed

- In the case of positive tests: A large shunt or unprovoked shunt is associated with certain forms of DCI (cerebral, spinal, inner ear, and cutaneous). Small shunts are associated with a lower but poorly defined risk of DCI

- If a PFO is demonstrated, options include:

- Stop diving

- Dive more conservatively

- Close the PFO

- The diver should not return to diving after PFO closure until satisfactory closure has been confirmed

My final thoughts:

Should all divers be screened for a PFO?

No. There is approximately a five-fold increased relative-risk of DCI in patients with PFO, but the absolute risk is still quite small

Should all divers with DCI be screened for a PFO?

No. Twenty-five percent of the population has a PFO so one would expect a similar percentage of divers with DCI to have a PFO. Not all scuba dives have the same risk of DCI. To paraphrase James Carville’s famous quote from the first Clinton presidential campaign, “It’s the bubbles, stupid”. The issue with decompression sickness is the inert gas “bubble load”, not the PFO. However, episodes of DCI in “low-risk” dives (especially neurologic, inner ear, or “skin bends” events) or multiple “undeserved” DCI events should prompt investigation for PFO.

Should all divers with DCI and PFO have a PFO closure?

No. Options for divers with PFO and DCI include discontinuing diving, instituting more conservative diving practices, or PFO closure. Recommendations should be made on a case-by-case basis based on the DCI event(s), the type of diving being performed by the diver involved, and the risks of PFO closure.

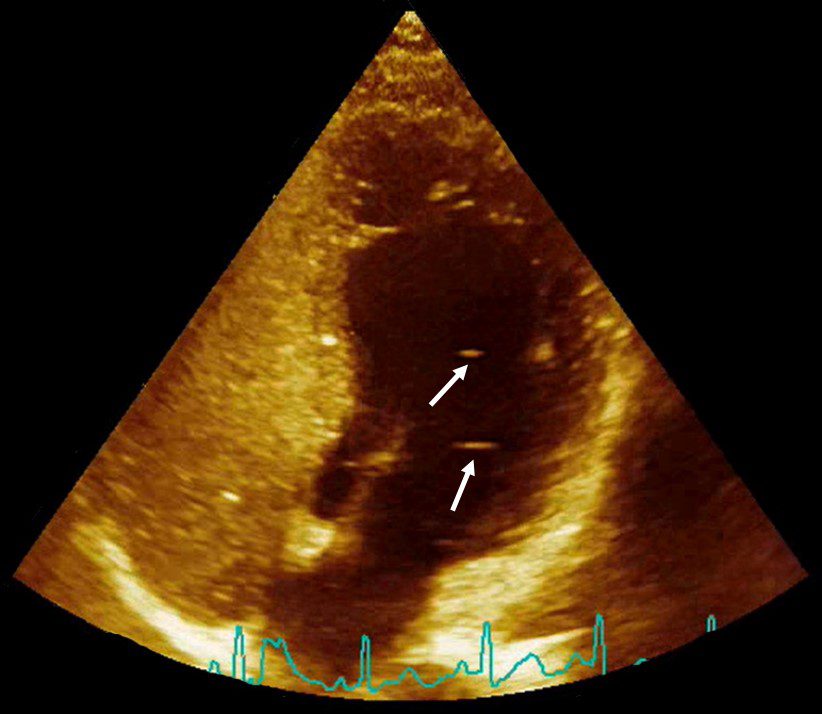

What does the header image (above) depict?

It is an image of a heart with a PFO. Clinical bubbles were injected in the vein of the person for diagnosing the PFO, you can see that they completely fill the venous chambers (left side of the image), and because there is a PFO a few bubbles can also be seen in the arterial chambers (pointed out by the white arrows – there’s likely a lot more, if you notice the bottom of the right side is brighter compared to the rest of those chambers and that’s actually because some tiny bubbles are crossing through). Note, the “clinical bubbles” I refer to, are agitated saline contrast which are large enough that they are filtered by the lungs and don’t appear in the arterial chambers unless there is a PFO.—V. Papadopoulou

References:

- Wilmshurst, PT, Byrne JC, Webb-Peploe MM. Relation between interatrial shunts and decompression sickness in divers. Lancet. 1989;334:1302-1306.

- Torti SR, Billinger M, Schwerzmann M. Risk of decompression illness among 230 divers in relation to the presence and size of patent foramen ovale. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1014-1020.

- Bove AA. Risk of decompression sickness with patent foramen ovale. Undersea Hyperb Med 1998;25:175-8.

- Hagan PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc 1984;59:17-20.

- Kerut EK, Norfleet WT, Plotnick GD, Giles TD. Patent foramen ovale: a review of associated conditions and the impact of physiological size. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38 (3): 613-623.

- Wilmhurst PK, Ellis BG, Jenkins BS. Paradoxical gas embolism in a scuba diver with an atrial septal defect. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1277.

- Moon RE, Camporesi EM, Kisslo JA. Patent foramen ovale and decompression sickness in divers. Lancet 1989;1:513-14.

- Germonpre P, Dendale P, Unger P, et al. Patent foramen ovale and decompression sickness in sport divers. J Appl Physiol 1998;84:1622-6.

- Germonpre P, Hastir F, Dendale P, et al. Evidence for increasing patency of the patent foramen ovale in divers. Am J Cardiol 2005;95;912-15.

- Gempp E, Blattearu J, Stephant E, et al. Relation between right-to-left shunts and spinal cord decompression sickness in divers. Int J Sports Med 2009;30:150-3.

- Schwerzmann M, Seiler C, LippE, et al. Relation between directly detected patent foramen ovale and ischemic brain lesions in sport divers. Ann Intern Med 2001:134:21-4.

- Schuchlenz HW, Weihs W, Hackl E, Rehak P. A large Eustachian valve is a confounder of contrast but not of color Doppler transesophageal echocardiography in detecting a right-to-left shunt across a patent foramen ovale. Int J Cardiol 2006;109:375-80.

- Gin KG, Huckell VF, Pollick C. Femoral vein delivery of contrast medium enhances transthoracic echocardiographic detection of patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1994-2000.

- Klingmann, C, Rathmann N, Hausmann D, et al. Lower risk of decompression sickness after recommendation of conservative decompression practices in divers with and without vascular right-to-left shunt. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine 2012;42(3):146-150.

- [Swiss Underwater and Hyperbaric Medical Society. Empfehlungen 2007. Der Schwiezerischen Gesellschaft Fur Unterwasser-und Hyperbarmedizin Zum Tauchen Mit Einem Offenen Foramen Ovale][cited 2012 June11]. Available from: http://www.suhms.org/downloads/SUHMS%20PFO%20Flyer%20d.pdf(German)

- Scott P, Wilson N, Veldtman G. Fracture of a GORE HELEX septal occluder following PFO closure in a diver. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2009;73:828-31.

- Wahl A, Praz F, Stinimann J, Windecker S, Seiler C, Nedeltchev K, et al. Safety and feasibility of percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale without intra-procedural echocardiography in 825 patients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008:138:567-72.

- Saguner AM, Wahl A, Praz F, et al. Figulla PFO occluder versus Amplatzer PFO occluder for percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2011;77:709-14.

- Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:991-9.

- Billinger M, Zbinden R, Mordasini R, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure in recreational divers: effect on decompression illness and ischaemic brain lesions during long-term follow-up. Heart. 2011;97:1932-7.

- Anderson G, Ebersole D, Covington D, Denoble PJ. The effectiveness of risk mitigation interventions in divers with persistent (patent) foramen ovale. Diving Hyperb Med 2019 Jun 30;49(2):80-8

Dive Deeper:

InDepth: No Fault DCI? The Story of My Wife’s PFO (12.2019)

InDepth: Undergoing PFO Surgery as a Team: Deana & Bert’s Excellent Adventure (12.2020)

InDepth: Uncovering the Link Between PFO and Inner Ear DCS (5.2019)

European Heart Journal: European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. Part II – Decompression sickness, migraine, arterial deoxygenation syndromes and select high-risk clinical conditions (JAN 2021)

Dr. Douglas Ebersole, MD is a cardiologist specializing in coronary and structural heart interventions at the Watson Clinic LLP in Lakeland, Florida. He is also an avid technical, cave, and rebreather diver and instructor. He can be reached at [email protected].