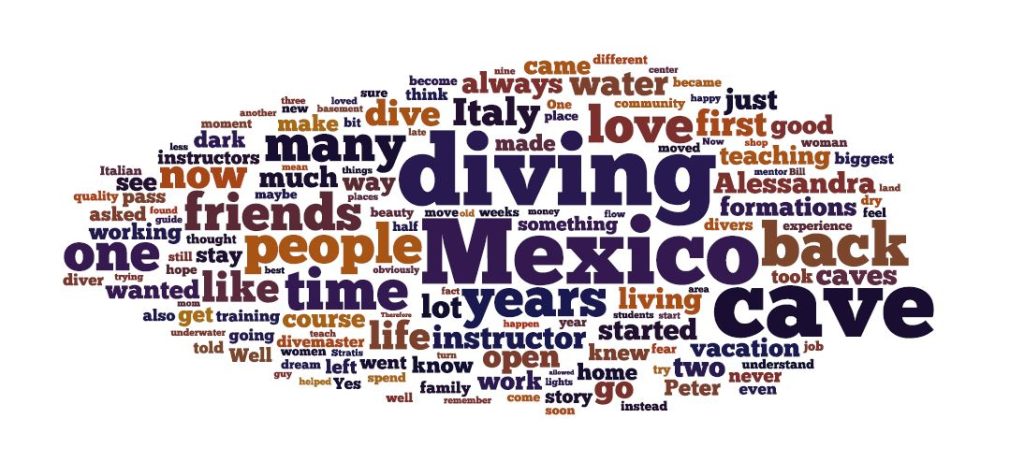

Cave

For The Love Of The Water: The Remarkable Story of Underground Aficionado Alessandra Figari

As most of us can attest, diving is a compelling activity that can change lives! It certainly did for Italian cave diving instructor, tech instructor trainer, and owner of Cave Training Mexico, Alessandra Figari, who left a comfy life in northern Italy at age 40 and moved to Mexico to become a cave diver, despite being afraid of the dark. Twenty plus years later, the Italian dive maven is still rocking, er wet-rocking the house while inspiring others, including cave diving instructor Stratis Kas, who interviewed her for this story.

By Stratis Kas. Images courtesy of Alessandra Figari unless noted.

🎶🎶 Predive Clicklist: Sounds of Silence by Simon & Garfunkel

What happens when you mix 50% courage and 50% adventure spirit at the age of 40? Well, one option is that you turn your monotonous life into a dream, move to Mexico, go against the rules, make new rules on your own, and dive for the rest of your life—while making a living from it. Or in fewer words, you are simply, Alessandra Figari.

My experience with Alessandra Figari started when we spoke about her contribution in my book, “Close Calls.” I knew her by reputation, but we officially met because of that. She told me her amazing story when we were preparing her story and biography. I was mind-blown when I realized that an Italian woman in her 40’s left the comfort of her bourgeois life in Northern Italy, left an extended family behind, and left the security of a good job—all for her love of water.

Alessandra, now 62-years old, is living proof that it’s never too late to start diving. She is a well-known, active cave diving and rebreather instructor, and tech instructor trainer through her dive center, Cave Training Mexico, which she founded in 2001, and an Associate Member of the Explorer’s Club of New York, as of January 2013. All of these accomplishments would have mattered little, had they not allowed her to engage in her one true love–diving.

I had the privilege to be hosted by and to dive with both her and her partner Peter Broger in Mexico. We dove everyday, and not a single day was Alessandra “working.” She generously shared not only the beauty and uniqueness of the Cenotes that is her new home, Quintana Roo, Mexico, with me, but also her love of the land itself and the people there. But even more generous is Alessandra herself. She doesn’t just dive with you. Being guided by her is a fabulous experience, as you can feel her love for the place, the land, and the people. Therefore, you are introduced more holistically to what this land represents, and not only the caves themselves. Mexico cave diving and Alessandra will always be synonymous for me. I asked her to tell her story. Here is what she had to say.

Stratis Kas: How did your love for water and diving start?

Alessandra Figari: My love for the water started many, many years ago. Ever since I can remember, I always wanted to be near or in the water somehow. As a child, I read many books about dolphins and watched a lot of documentaries about their interaction with each other and between humans. My dream was to work as a marine scientist to understand them, their language, their interaction. At 18, I wanted to study oceanography or marine biology, but I was discouraged by my family. My father said, “No, study languages.”

Some years later, when I was 25, I underwent a leg surgery that kept me on crutches for four years. During that terrible time, I visited Barbados, and dove in the Atlantis submarine. That was my first time to ever be underwater. How spectacular it was! Right there, I decided that I wanted to be outside the sub in the open water to see the real beauty of the ocean. As soon as I got rid of my crutches, I went to do the open water course, but it never happened. Instead I did a Discovery Scuba Diving program, a one-day kind of course, over and over again. For almost 9 years, every summer I did the DSD and I was diving because of it. Finally, after these nine years I had a logbook with 30 maybe 40 dives or more.

In 1998, when I finally took my open water course in Milan, Italy, once in water I was obviously someone who was already diving for nine years. So after the first pool dive they told me “you are a secret shopper from PADI!, you know all the skills, you don’t make any mistakes, you look like you have a lot of experience!” So I laughed and said, “yeah, nine years of DSD and diving does that!”.

What happened then?

After getting certified, I started doing open water dives here in Mexico while I was on vacation. During that vacation I had a love affair with an American who was the manager of a diving center here. As soon as I went back to Italy, he invited me to come back. I always wanted to live close to the ocean and be involved with it somehow, so this was a great opportunity. Without too much thought, I left my “regular” job as manager in a non-profit company, which obviously created a big shock in my very “normal” family. They thought that I was crazy. But I made my decision, moved to Mexico and started working in a dive shop as a receptionist. During that time, I did all my courses there and fell in love with the cenotes.

How did that happen?

Diving the cenotes touched a very traumatic memory for me. When I was a kid, because I was not eating very much, my babysitter closed me in a dark basement. So I developed a fear of the dark. As you may imagine, cavern and cave diving while fearing the dark? Nope! It was not exactly a perfect match. But I loved them so much that I was going to find a way to conquer my fear.

During one of my trips in Italy, I found a guy who did work on past trauma issues, and he was a dry caver himself, so he could understand me better. We ended up doing a lot of work together and he took me, finally, with no lights, in a dry cave for two hours walking. No lights, just touch. Staying there 20 minutes, half an hour, without speaking, just “listening” to the stunning silence of the cave. No lights! I had a small backup light in my pocket just in case I felt too uncomfortable. That’s how I did it. Shortly after that, I did my first cave course. I knew that I could go through with it. Now I love caves so much, I feel at home in them.

That experience in the dry cave changed something in you?

Yes, I came to realize that my fears were related to a kid of two or three years old in the basement of a house. That the “scary” sounds were normal for a basement. That being afraid of the dark didn’t make sense. Walking in a dry cave made me get the perception that there was nothing to be afraid of in the dark. While I was in Mexico, I was diving in the caverns as a rescue diver and divemaster. My problem was that I knew that if I wanted to get into the caves, which was my dream, I needed to be sure that I was not going to freak out because of the dark.

And why? I’m only asking because I have a similar story to yours, why do people dream of becoming a cave diver? It must have been quite unusual for a woman back then. Women have a brain that thinks more logically and rationally. They don’t have the need to prove much to others. What was it with you?

I loved the formations. Also, obviously living in the Yucatan, most of my friends were cave divers or cave instructors. So I started seeing pictures from the caves. The two things that attracted me were the beauty of the underwater landscapes, meaning formations, passages, the colors. Yellow, dark, browns. The beauty and the fact that not so many people were going there, then, made it a truly special place for me.

So you didn’t move to Mexico for cave diving, you moved to Mexico and Mexico brought you to cave diving?

Yes.

What was the reason you moved to Mexico?

My first time there, I was on a vacation with friends. And then came the love story. After a year and a half, when my love affair ended, I asked myself, “Should I go back, or should I stay?” So I decided to stay. I had a job in a dive shop and I became a divemaster.

Was there a moment when you knew that your “previous life” was gone? That it was inevitable? Tell me about that moment and how do you remember it?

I was working here as a diving instructor and on my way to become a cave instructor. When I left Italy, my old boss told me, “Whenever you want to, come back and I will give you a job.” After seven, maybe eight years, there was a moment when I realized, well it’s too late anyway to go back now!. That was it. I never really thought that I was closing a door or opening another. I was already planning my “other” life.

Did it feel that diving was your calling, what made you happy?

Since I started living here, it was all I wanted to do. I opened my company, Cave Training Mexico and did my cave instructor training with International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD) in 2007. I was doing the things I wanted to be doing, and even when I “looked back” for a second to how my life was before diving, and I “saw it” again for a moment, I knew that I was doing what I loved. And there was no going back.

Your story has always been this inspirational story of “You had something that was solid; you had a routine, you had your life planned. But it was just not enough, so you took a great chance and dared to go down the unbeaten path.”

At what age did that happen? Because that is also amazing—that it didn’t happen when you were 25. I have been using this myself as an excuse when my friends tell me, “Why don’t you become a full-time diving instructor, isn’t it what you love?” And I always say, “If I was 25, I would do it.” I have been saying this for 12, 13 years now.

Do it!

So, you did something most people, even when they dare, do it when they are young. But you did it much later in life. It was such a bold thing to do. And on top of that, being a woman, which was different back then than now. Plus, you know, from Milan you didn’t move to Geneva—you moved to Mexico!

There was a small kick in my butt, if I can say that. The year I went for vacation in Mexico was the year that my father died. Then, six days after his funeral, my ex-husband asked me for a divorce. So, like we say in Italy, you get a slap on one side and then you receive one on the other, and so you stay straight on your feet. During that first trip to Mexico, the friends with whom I was traveling told me that instead of staying only two days in Akumal at the beach, they were willing to stay for a week so that I could go diving. The result? I stayed three weeks. For two weeks my friends traveled around Mexico, but I dived the entire three weeks! That was the beginning of my love for this place.

When did you start feeling that Mexico was home for you? And I know you’re still Italian at heart and you feel like it is and it isn’t, but tell us more…

For me, it’s half and half. And it will probably always be. I have a home in Mexico, and I have a home in Italy. Not just physically speaking. But I have many good friends and my family in Europe, so my “home” is shared between two very different places.

You spend most of your time in Mexico. Is it like 10-11 months there and then maybe one month in Italy?

Well, I spend a bit more time in Italy than a month, but we are not talking about physical time, we are talking about emotional “time” I think.

True.

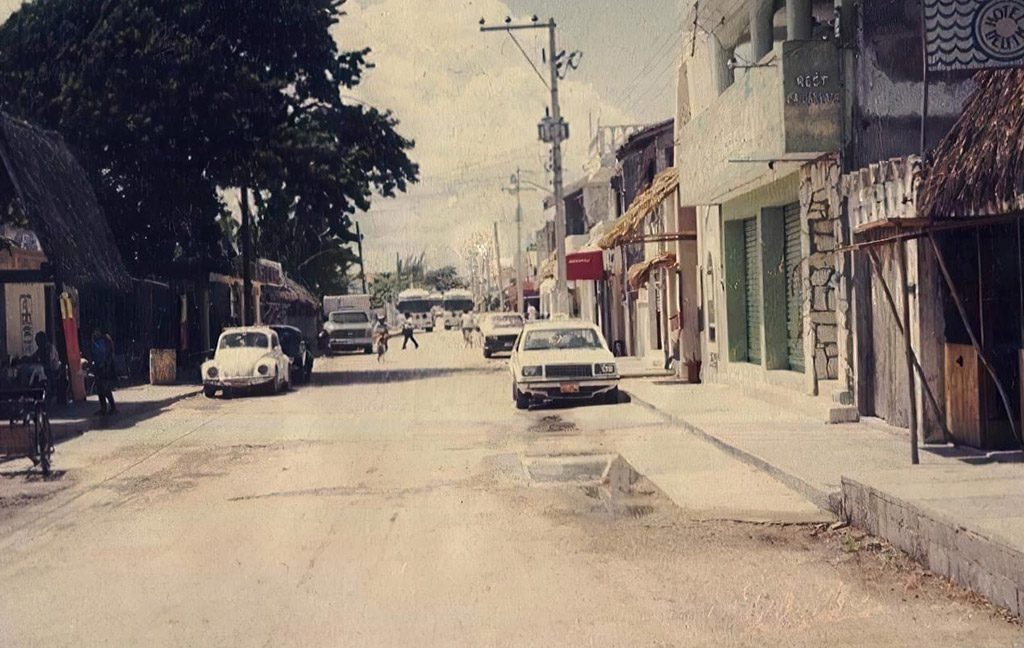

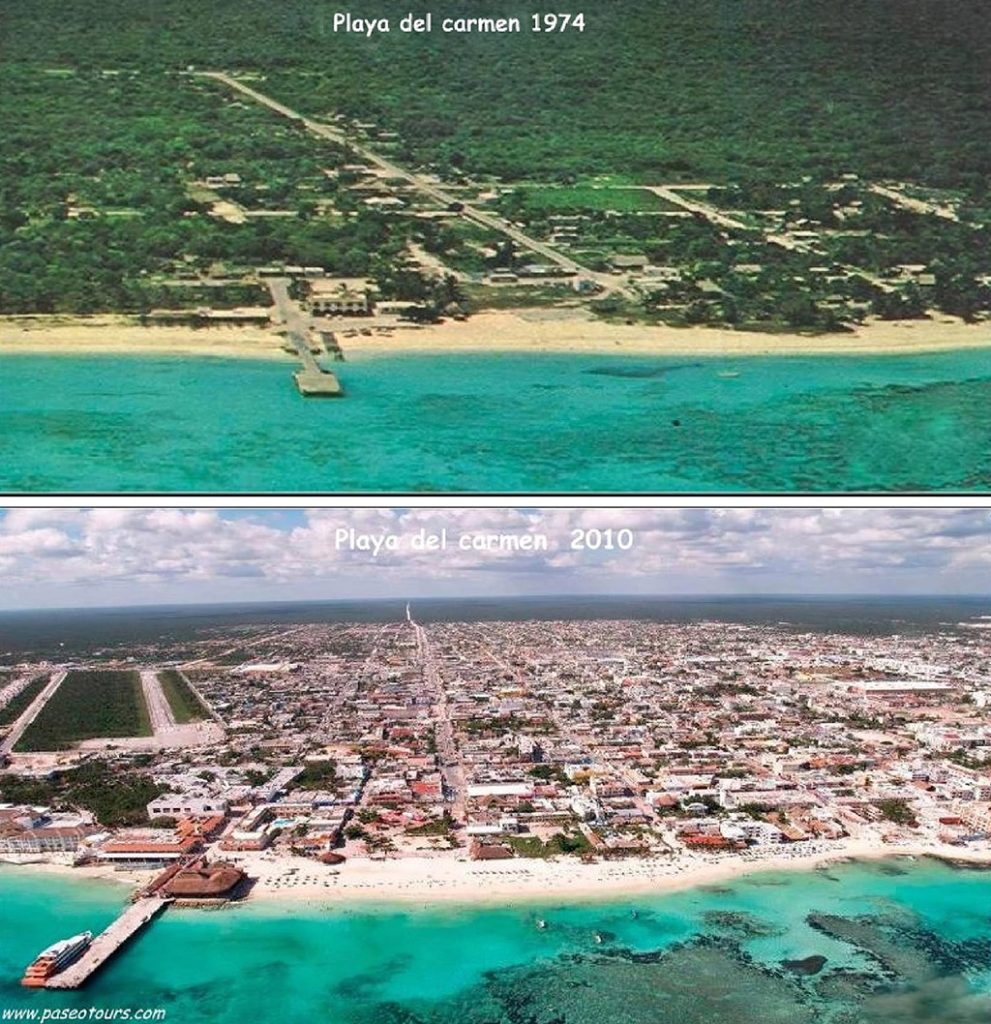

I have both places in my heart. On the other hand, coming to Mexico was easy compared to many other places, in a way. When I came here, 20 years ago, Mexico was like the South of Italy in the 50s, so it was really easy, if you understood the Italian mentality.

What was different back then if you compare it with how it is now in everyday life in the diving business?

Back then, there were a lot less people. We knew each other. We were all friends and respected each other’s business. We were loyal to each other. Now there are a lot of new people coming in, and it is not the same. Back then, we left our cars open. I mean open! If someone needed something, they would take it, and leave you a note saying, “I took this, I will give it back as soon as I’m out of the water,” and there was no problem. Nowadays, if you leave your car open, you are in trouble.

That’s a huge cultural shift!

In the past, more or less everybody charged the same prices. We were a lot more equal in the value we were offering through our work, if that makes sense. Now, because of the competition, there is much more to offer, but the clients have not proportionally increased. The competition got ridiculous. The prices in some services offered dropped so much that it’s ridiculous to even try to compete, unless you are willing to work for free. And the quality is suffering. Those who try to go cheap at “any cost” are also offered lower quality products.

It’s unfortunate. So, do you have any regrets about moving to Mexico?

Maybe now that we have started traveling more with Peter, like to Switzerland or to visit Italy a bit more often, we spend more time there. Maybe also because we are getting a bit older. I can appreciate some of the good things about Europe more now.

How did your friends and family make your decision to move to Mexico?

My friends took it well because they saw that I was happy. My mom, for two years, told her friends that I was “on vacation”. I found out by pure chance. During one of the times I was visiting her back in Italy, we went to the Scala Opera together. One of her friends said, “Oh, good to see you, how was your vacation?” And I said, “Very good,” because I didn’t want her to act weird with my mom. But when I took my mother back home I asked her “What is this story of the vacation?” And she said “Well, you know I didn’t know how to explain it, so I said you were on vacation.” So I said, “Okay Mamma, maybe we can pass on the next phase, and say that I work as a dive instructor now and I spend time in Mexico for work. She agreed and from that day on, I shared with her my adventures, photos and videos and she enjoyed them even if she always told me “I love to watch you doing what you do, but it is scary for me”.

I understand that your family has never visited you in Mexico.

Only my brother. My brother and my sister-in-law, with their kids, came.

It’s been many, many years.

My mom and my sister never came. I think that maybe for them it was as if I was living on Mars or worse. Yeah, they never came. I think they lost, not me, in the end. So, now I am waiting to see if my sister will come at least once. I have invited her many times.

So how was the life of a foreign woman trying to live and work in a country like Mexico back then? What were your biggest mistakes and what were your highlights?

First of all, one of the highlights was that I had very good friends, but only a few and, these friends truly helped me. One of them, who now is my partner in life, and in crime, is Peter, who for many years was one of my best friends. Some others allowed me to stay in their hotel without paying for my room for two weeks and then helped me find a place to stay. Some other Italians gave me a studio on top of one of their restaurants in the city center. In front of that studio there was a bar that made a lot of noise and that stayed open until late, but the guy became a friend of mine, so we made an agreement that until midnight he could have music and the doors open. And, I could have a free drink every night if I wanted. But after midnight, he closed the doors so that I could sleep, because he knew I was diving early in the morning.

That’s nice.

Yes, that was the mood of the people who were living here back then. They were friends. So many of these people helped me to deal with all the difficulties I had to face.

You were one of the first women cave diving instructors in the area?

There were four women working in the area before me, one was from Switzerland, one form Mexico City, and two were from the US.

They were living there, or they were just passing by to teach and explore?

One was Karin Buchel and the other Virginia Urbieta. They were living in Mexico full time and Karin in this area; Kay Walten and Nancy DeRosa were not living here and they were amongst the first explorers of many of the caves of Quintana Roo.

How about today? What percentage of cave diving instructors are women, more or less?

I don’t know exactly the percentage. We are now a lot more. I think probably there are about 30 to 45% women instructors compared to 60 – 70% of men.

We need that. The community needs that. Hear hear! When and why did you get involved in technical diving?

When I became a cave diver, I was looking for an instructor that was not macho, who was not too impressed with himself.. Then I found Bil A. Phillips. When I talked with him, I liked the way he was, so I asked him if he could do my cave course. I went on my first day having everything ready, all happy, and we started filling the paperwork. At the time, I was just a divemaster. So, Bil looked at me and said, “You are a divemaster?” And I said, “I am, yes.” “Oh my God,” he said, “I’ve only been teaching instructors until now for the cave course.” And so I started laughing as I said, “Well, I guess this is going to be your first time; after all, there is always a first time in life.” After that, he became one of my best friends. Unfortunately, he passed away far too young. But for many years he was my best friend, along with Peter.

Have you dived caves anywhere except Mexico?

Florida. I love Florida caves. However, they don’t have as many formations. I mean, they are more like underwater rivers, with strong flow pushing you out. High flow. But I love them for the way they are. The fact that you have to fight to go in against the flow and the cave shoots you out, like it’s trying to expel you. They have beautiful rock formations and depth. So you have to remember when diving that on your way back you should try to stay a bit shallower because otherwise you will get a lot more decompression. Therefore, it is a completely different way of diving. But they are very beautiful caves. Next on my bucket list is Greece. There is a guy that I know called Stratis who might take me.

You’ve been an instructor of various levels for a long time. What do you love about teaching? Why is it so compelling to you that you teach most of the months of the year?

Because I like teaching. I always liked passing on information and helping people to obtain more knowledge. When I was at the dive shop as a receptionist on my way to becoming a divemaster, I was teaching languages. I was teaching Italian, English, and French to kids. So, I like teaching in general. I like to see people growing through their knowledge. That’s the reason I like teaching, and I still teach.

Any names that come to mind when the word mentor is mentioned?

As far as my being a mentor, many of the professionals that are working here were my students for their open water instructor level and some for their cave training. Some thought I was too strict and complained, but they still came back to do more training. So something worked, right? Something good I think came out. The fact that many of them went ahead and opened businesses and are now recognized in the local and international community must mean that I taught them something.

My mentors? Yes. Bil Phillips, for sure for cave diving. Andreas W. Matthes was another of my mentors. Peter Broger, because I learned to dive and guide with Peter. Peter was a very, very serious instructor at the time and still is now. He was training new people who were working in the local community, working for him mainly. He asked me to assist with many cavern guided tours and then to guide the tours myself while he was checking what I was doing. He was for sure one of the people who made me a good cavern guide because of the time he spent with me. Georgia Hausserman was another very prominent mentor. She was the person who introduced me to CCR. And Paul Heinerth, with whom I did my first sidemount course.

One of our giants! What is your biggest fear for the future of cave diving in Mexico, and what’s your biggest hope?

My biggest fear is that the “Mayan train”will collapse the caves. But also, the mass infiltration of poorly trained divers who will impact the cave systems. On the other hand, my biggest wish is that the pollution from the population growth of the area will not affect the caves too much—that the developers will make an effort to protect the resources and the people affected by them.

From a diver’s perspective, I hope that cave diving industry will continue protecting this unique environment, and that visitors will understand and appreciate formations that are millions of years old and respect them and not try to pass in areas where they may hit the formations, but instead, remove their tank and make sure that they can pass clean. In the last couple of years, you can see the damage from the tanks on the formations because more and more people think they can pass instead of removing their tanks and making the effort to see if they pass. They just go on and bang…

You’re referring to sidemount diving?

Yes, because even with sidemount, a diver cannot always pass through a restriction. What happens is that divers turn on their side, but then they often turn back straight too soon, and the bottom of their tank hits the formations. If you dive a lot and pay attention, you can see the damage. This is a pity.

So what do you see for the future of Mexican cave diving?

Well, I hope it will stop being so commercialized. Meaning that instead of money, money, money, we get back to quality—both in terms of the requirements for people to become cave diving instructors, as well as for people to become cave divers. I have stopped courses, and asked students to go get more experience diving at the level there were, because they were not ready to be cave divers. Of course, this doesn’t make me popular. But I hope that the community’s teaching philosophy and practice will evolve to where quality, evaluation of standards, and the capability of the students will be maintained at an appropriately high level.

Thank you Alessandra!

Dive Deeper

Website: Cave Training Mexico

Tec Dossier – Alessandra Figari – English (NOV 2013)

Vimeo: Alessandra Figari Enjoying Diving Mexico

Speaking Sidemount: Episode #77 Alessandra Figari – “Follow Your Dreams”

InDEPTH: Save the Cenotes

Diving instructor, filmmaker, adventurer and storyteller Stratis Kas, deals with all of his subjects—from expeditions in extreme weather to days lost in wilderness—with unique sensitivity and fearless focus. He travels to remote, sometimes risky and often freezing locations to create stunning films that change what we know about diving expeditions. Stratis’ interest in making a real connection with nature is reflected in his ability to shift from filmmaker to explorer.

From 2016 to 2019, Stratis has founded and led the Top2bottom cave filming team that specializes in adventure filming. In 2017, he completed his first film Amphitrite which was selected as a finalist in the SHORT to the Point, the International Short Film Festival in 2018. Amphitrite was the first effort of presenting Greece as a Cave diving destination to the global community. He presented the film at the Tekdive Europe International conference in Belgium. In 2019, Stratis went solo and continued with mixed teams to develop the promotion of Greece as a valid Cave destination. he completed his second film, “Infinite Liquid”. In 2020, Stratis started developing his first book, “Close Calls”, which is now considered a must have book for any diver.