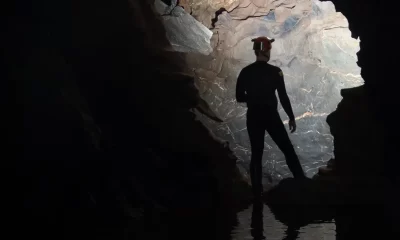

Cave

Andy Torbet: The Swiss Army Knife of the Diving Community

In this era of heightened stress, dive engineer and content producer, Carlos Lander thought it useful to speak to someone who manages prolonged stress in extreme situations. That man is Andy Torbet, a former British special forces officer, cave diver, freediver, rock climber, sky diver, BBC host and producer and DAN Europe Ambassador. Oh did I mention he’s Daniel Craig’s stunt double in the new 007 movie, “No Time to Die.” Here’s what Torbet advised.

by Carlos Lander. Photos courtesy of Andy Torbet

The COVID-19 pandemic has created new stressful situations that have raised our awareness of the impact of stress on our mental and physical health. I was, therefore, enthusiastic to talk with Andy Torbet, someone who has—in the past and present—successfully managed prolonged, extreme stress in survival situations.

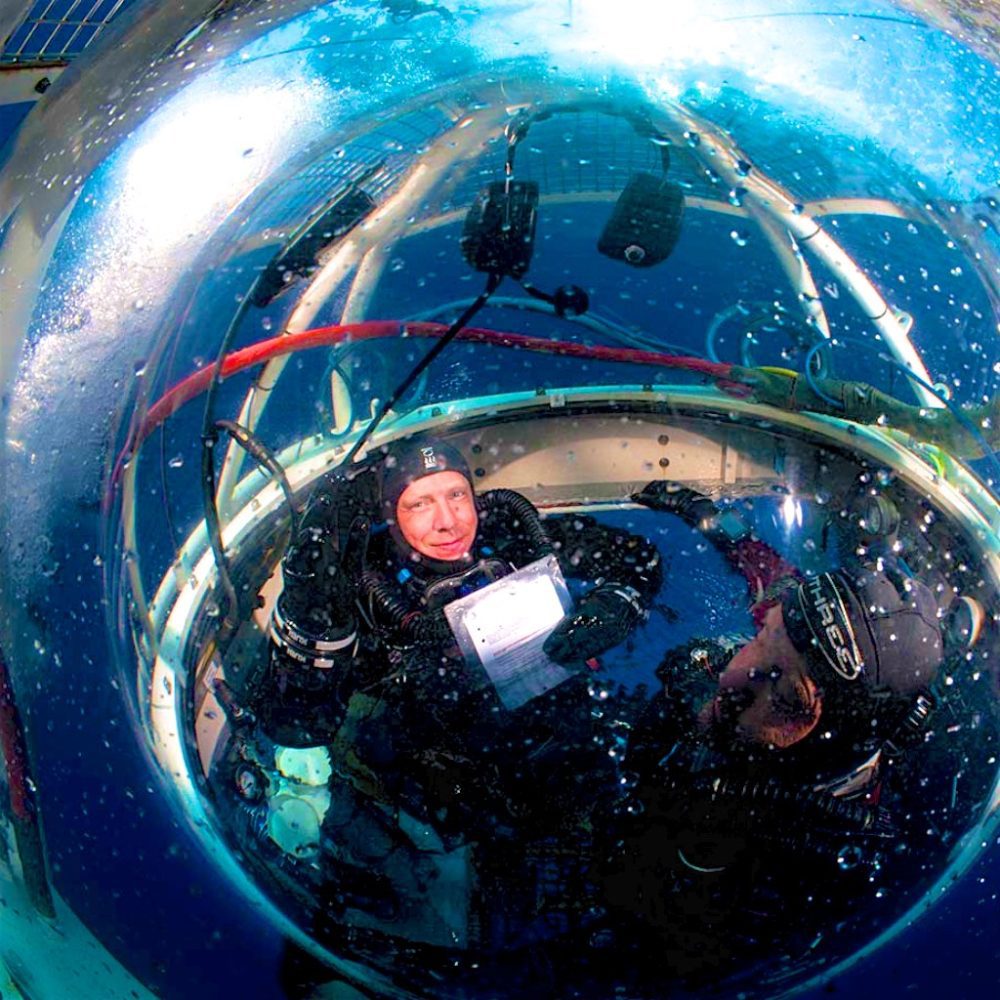

In his former life, 45-year old Andy Torbet was a bomb disposal officer and maritime counter-terrorism agent for the British Army. When he made the leap to civilian life, he remained within the realm of extreme adventures, becoming one of the finest Briton underwater explorers; he’s a professional cave diver, skydiver, free diver, climber, TV presenter, and filmmaker. His most notable programs include BBC’s The One Show, Coast, Operation Iceberg, Operation Cloud Lab, Britain’s Ancient Capital, The People Remembered.

He co-produced the children’s BBC series Beyond Bionic, which was adapted into a computer game: “Beyond Bionic—Extreme Encounters.” Torbet’s first book, Extreme Adventures, was published in 2015, and he became a host on Fully Charged in April 2020. More recently, he can be seen in the new James Bond film, No Time to Die. He’s obviously a guy who excels in many fields, so he’s familiar with stress and has some ideas about how to cope with it.

Torbet’s prolific diving career memorably includes the Britannic expedition in 2016 for a BBC documentary. He was also involved in “The MV Shoal Fisher—The Mystery Shipwreck,” about a wrecked World War II merchant ship in the English Channel. Andy himself admits his solo exploration of The Cave of Skulls, Scotland’s deepest pot hole system, was “probably the most hardcore” of his adventures. That dive involved crawling through tight and flooded passages, getting stuck, and finally releasing his breath hold just enough to squeeze out of trouble. His book vividly details the harrowing dive and takes readers on a spine chilling adventure, as it did me.

When thinking about Torbet, a Swiss Army Knife comes to mind—an instrument designed to be useful in many situations. Another analogy might be Tony Stark without the Iron Man suit. Or, perhaps, a modern-day Sir David Attenborough. When presented with these options, he happily chose the knife comparison. Mr. Torbet has a compelling set of tools to call upon: He’s a loyal family man, has a sense of purpose, is resourceful and righteous, a teacher, and a risk management expert who can compartmentalize, communicate, and be playful. Oh, and he’s humble.

Torbet began his journey in the beautiful Scottish highlands. Born in 1976, he was an outdoor kid, climbing trees and playing in the lochs with his brother, who has joined him in many adventures over the years. At 20 having finished his university degree in zoology, Torbet joined the Army, inspired by his brother who had enlisted when he was 16. Torbet also admitted that joining the military was a way to see the world—it appealed to his desire for adventure—and to “make some decent money.” According to Torbet:

“Anyone can have a desire for exploration, but desire won’t get you there; action will. That doesn’t mean being reckless. It means taking the time to build discipline and to acquire the skills and knowledge you need to do whatever you do safely, also balancing the risk with sometimes needing to say, ‘Fuck it, here I come!”

The Torbet Method for Managing Stress

Mr. Torbet has three favorite sports: diving, skydiving, and “Esoteric Climbing” (where the bedrock is likely to be loose, fragile, and crumbling). Andy explained that, while climbing, he does not need to look down, because he knows how much distance he’s covered. “Even in this type of climbing, when I’m not or I don’t feel entirely in control, I don’t look down,” he said. “It won’t do any good.”

Why? Sometimes we can’t change an external situation, and that shouldn’t affect our emotions. What is important is how we react and how we reframe it. As Torbet put it:

“What we choose to do and how we choose to act is what counts, and this is all within our power to influence. In fact, sometimes when injuries are crippling us, time is against us, the weather is beating us back, and our kit is failing. Our attitude—the mindset we hold as we walk through the world—is the only thing we can control.”

Although Torbet has been in many military incursions, he prefers cave diving as an example of managing stress since, in his opinion, underwater caves are the most hazardous environments available to us. “[Underwater caves are] an alien world here on earth, and from a psychological point of view, very oppressive,” he explained. “It’s dark, isolated, cold, and claustrophobic. Therefore, we must deal with those realities long before we enter the cave.”

There are a few things that Torbet believes we should do to manage stress. First, evaluate the “what if” scenarios familiar to the diving community. Second, gain and maintain proficiency in the skills needed to manage those situations. Third, have the proper equipment and make sure it has been tested. And last, we must be mindful of what we are doing at all times. He also posits that, in an emergency, having fewer choices is better than having many; it reduces the time needed to choose a plan of action and allows us to more easily draw on our training and preparation. Not all situations can be foreseen. As Torbet explained,

“Do not lose yourself in emotions. Be present. I could be a mile from the cave exit; it does not matter. My concern is with the moment. I know that because I prepared myself, I have a proper plan for contingencies. Something random that I did not expect may occur, but I remain calm, focused on making my way out. I do not succumb to emotions, and I am focused because I prepared myself mentally and physically for this. You don’t save your life at that moment, you save your life in the days, months, and years before that.”

In this way cave diving is reduced to managing a sustainable level of pressure during prolonged periods of time, while maintaining concentration on techniques.

A Team of One?

Solo diving is a reality of exploring caves in the U.K. Paths are often so narrow that sometimes divers need to crawl, and more than one person will not fit. In tight spots, you’re on your own to handle difficult situations.

Torbet’s experiences have taught him that, even during team dives, sometimes you need to focus on yourself without distraction and without accepting responsibility for others; Andy experienced this in his Cave of Skulls explorations. Everyone needs to make their own decisions, trust their own gut feelings, and be vocal when things aren’t okay.

In his case, the Army trained him to put fears aside and get on with the job at hand. Andy specifically wrote in his book that, in the armed forces, the only option is to man up. When his teammates experienced difficulties during the Cave of Skulls dive, he decided to continue his adventure alone. [Ed. note: Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) does not sanction solo diving.]

“In situations like these—that not only require technical skills but also are potentially dangerous—it is easier to just look after yourself. But, in the vast majority of dives, you’re better off having a teammate. Being alone isn’t just less fun, but it also requires resilience that only a select few—and highly-trained—divers have.”

After he reached the end of the cave, Andy felt a moment of quiet satisfaction and peace. But, of course, his adventuring didn’t stop there. Andy’s current project and focus? Becoming a stunt double.

Stunt Doubles

Managing stress as a stuntman requires individual concentration while your safety is in the hands of others. Torbet’s a bit uncomfortable placing responsibility for his safety in a crew, but he is learning to accept it. He said that he has a great deal of respect for this community, and it was a wonderful opportunity to work on a variety of films. “My last project, James Bond as 007 in No Time to Die, was an incredible experience.” I asked him if he could elaborate, but he said he was under a non-disclosure agreement and couldn’t say more.

Torbet is eager to keep doing these kinds of projects, and he explained that stunts in an action movie require a lot of rehearsal and coordination between different teams, performers, cameramen, and safety crews. It is all extremely streamlined, like a dance between crews. Any stunt person, whether in a blockbuster movie or a documentary, will report that planning is required in order to prevent life-threatening peril. Nothing is left to chance. For all these circumstances, preparedness is key (physically and mentally). Timing and self-confidence are paramount. And, like Torbet’s observation about diving, you save your life long before you start.

Why does he love being part of the stunt community?

“They are a real brotherhood, it’s a family atmosphere, and they look after each other. They are extremely motivated, talented, and self-disciplined people who want to get the most out of life. Although they are super adventurers, they also have the skills and bring their game up. On top of all that, everyone that I’ve met is a thoroughly decent human being.”

A Perspective on life

Torbet is constantly in motion, always growing. He recently got his master’s degree in Archaeology. His plan is to write his doctoral dissertation on studying caves. His diverse interests and activities are always driven by passion. He teaches that adventure is personal and that even by walking on the path others have taken, it is still possible to own your journey, to fill it with new experiences and feelings.

“Everyone is different, and what works for me does not necessarily work for you,” Torbet advised. For him, compartmentalizing is a way of dealing with his life experiences. What happened in the armed forces stayed there, and he doesn’t share it with his family or mix it up with his other activities.

I think Torbet’s secret is focusing on the moment. Taking pleasure from his job at hand, filling his time with projects and family. Teaching his kids about the pleasure of nature and freediving when he has spare time. As he told me on more than one occasion, “Your happiness is dictated by the people you surround yourself with.”

Dive Deeper:

Fourth Element Wetnotes: My First Time-Andy Torbet

Read about Andy’s past adventures as well as his current projects at Andy TorbetProjects | Andy Torbet

Amazon: Extreme Adventures by Andy Torbet

Rising: Meet The Man Who Dives 100m Deep Into Caves One Kilometre Underground

Dive Odyssey—A meditative journey into the depths of water and mind

Beyond Bionic Andy Tornet TOP 3: Andy Torbet from Beyond Bionic tells us his top 3, like his favourite foods, memorable moments and inspirational people!

Find Andy Torbet’s “close call” story in Close Calls by Stratis Kas.

I want to thank Andy for his openness and candor with me and the diving community. He was kind to me, letting me pick his brain. He is truly a gentleman. I really enjoyed our conversations. I hope we can drink a pint or two in an Irish pub in the future and go diving.

Carlos Lander—I’m a father, a husband, and a diver. I’m a self-taught amateur archaeologist, programmer, and statistician. I think that the amateur has a different mindset than the professional, and that this mindset can provide an advantage in the field. I studied economics at university. My website is Dive Immersion. You can sign up for my newsletter here.