DCS

Between the Devil and the Deep and the DCS—My Own

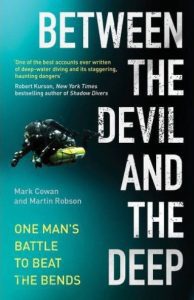

His new book, Between The Devil and The Deep, which was released last summer, delved into the ordeal of British cave instructor Martin Robson, who suffered a life-threatening, deep-water onslaught of DCS at Blue Lake, Russia. But, just after the book was released, Mark Cowan suffered his own debilitating, inner ear hit while diving the SS Wisconsin in Lake Michigan that has left him reeling for answers. Here is the intrepid diver journalist’s first-hand account.

by Mark Cowan

I STARED straight into the empty chamber where the sickest of divers went, eyes hopeful as the world spun anti-clockwise around me. I sat in a wheelchair at St Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee shortly before midnight on August 7, and listened as Dr. Gerald Godfrey said the treatment for my complex case of decompression sickness would be relatively straightforward.

My world was spinning, literally and metaphorically. Vertiginous feelings had tipped my life on end after I had completed an uneventful summer afternoon dive in Lake Michigan, Wisconsin, eight hours earlier. I was unable to walk unaided, my balance had disappeared, and I couldn’t focus on anything because the horizontal and vertical hold on my vision had vanished.

Earlier that evening, doctors in a hospital emergency room wired me up to a heart monitor and administered fluids, oxygen, and an antihistamine (for nausea) to stabilise me. Then, they transferred me to St. Luke’s—home to one of the earliest hyperbaric medicine programs in the US—for treatment.

Three doctors were waiting for me when I arrived at the hyperbaric department at 11 pm. Three doctors? I guessed they were there because they had not seen anyone like me before; it turns out they had rarely seen divers with decompression sickness.

There are no good “bends” to get, but if there were, mine was not that kind. I had a case of pure or isolated inner ear decompression sickness. The manifestation of inner ear DCS was, in medical terms, incompletely understood and infrequently seen in divers. The small number of studies concerning the issue offered a perplexing series of possible causes.

Examining me, the doctors spoke of neurological deficit and labyrinthine dysfunction. They used names like Sharpened Romberg—a test to measure my balance—and they also used other gestures of their own design to expose the worst in me. Dr. Godfrey, my primary doctor, asked me to follow his index finger with my eyes. The further his finger moved to my left, the more my vision seemed to skip back and forth. He described this condition as “Left-beating nystagmus of the third degree.” “Nystagmus” sounded so disconcerting. (Nystagmus means abnormal eye movement.)

A video had been taken on my cell phone earlier that day by an ER doctor to help me understand what was happening with my vision. Watching the video some days later, I saw my pupils involuntarily bounce back and forth like a rubber ball.

While inner ear DCS is unusual, the therapy was the same as if I had been suffering from joint pain—a US Navy Recompression Treatment Table 6. The procedure was—as accepted medical wisdom goes—the gold standard for DCS, and five hours spent putting me back together again didn’t seem so bad.

Shortly before midnight, I was wheeled into the chamber, and the medic accompanying me closed the door behind us. I leaned back in the chair as the incoming gas hissed into my ears. When the chamber reached the depth of 18 m/60 ft, the medic placed a plastic hood over my head and opened the valve to let oxygen flush into my lungs. I breathed slowly and deeply and waited for my vision to stabilise.

After 20 minutes, the medic removed the hood, held her hand in front of my face and asked, “Can you follow my finger with your eyes?” As she moved her hand to my left my pupils beat back and forth.

Things will be better next time, I told myself.

Twenty minutes later, my balance had improved slightly, but the nystagmus was still beating. Next time? The medic called Dr. Godfrey and he watched through the porthole as my pupils still bounced back and forth.

Recovery was not going well. I had been in the chamber breathing high concentrations of oxygen for an hour under pressure, and right then I couldn’t see any improvement in my condition.

The Dive

Earlier that afternoon, as the dive boat powered back to the port and I felt the waves of Lake Michigan wallow inside my head, I didn’t immediately suspect that anything was really wrong. My first thought was that I had early signs of motion sickness. My second thought was I needed to get some air. My third—if I had one—was that this was a sour end to a great day of diving.

Friends and I had spent the afternoon exploring the shipwreck of the SS Wisconsin, 40 m/130 ft down off the coast of Kenosha, Wisconsin. Once we got back to port, we had plans for dinner. There were stories to share and another dive to organise. Apparently, someone had found a way into the engine room.

The dive had gone as expected. Underwater, I had examined historic cars—including a Hudson Super Six automobile in the stern cargo hold—and I pushed further into the forward hold than I had been before. There, amid the debris, I saw the cargo of radiators stacked on pushcarts alongside furniture, ladies’ shoes, stoves, and rolls of hoses. That was a small slice of American Midwest history, right there in front of me.

After 39 minutes on the bottom, I began my ascent. The 17 minutes of decompression I had amassed was nothing onerous. After completing all my deco stops, and with my two computers clear, I surfaced and climbed up the ladder back onto the boat, happy. The skipper had taken a photograph of me minutes after I exited the water. There I was, sat on the dive bench, still wearing my rebreather, with a smile on my face.

But, as I sat there smiling, trouble was already bubbling inside my head. I couldn’t feel it, but that trouble was working from the inside out. An hour after the photograph was taken, it boiled over.

The first thing to go was control of my stomach. As the boat arrived in Kenosha Harbor and approached the quayside, I hung over the side and vomited.

The next thing I lost was my balance. Stepping off the boat, I set off toward my car. The ground pitched and pulled in odd directions beneath my feet like a carnival funhouse floor trick. I see-sawed across the car park, and my head felt fuzzy, intoxicated. To anyone watching, I probably looked like a drunk, too.

Then, my sight went haywire. Suddenly, I couldn’t tell left from right, up from down.

I dropped to the ground beside my vehicle.

“I think I’m in trouble,” I said to my buddy Robert Personen as he carried his bail-out cylinders from the boat. “Can I have your O2?”

As much as I didn’t want to admit it, I knew I was suffering every diver’s worst fear. I’d even written a book, Between the Devil and the Deep, about decompression sickness, published just three weeks earlier, and all the research I had done left me with no doubt about what was happening to me, and nothing about the situation was good.

In the chilly afternoon hours of August 7, I sat on the rain-soaked asphalt, propped against my car, sucking oxygen from the tank like my very life—and everything I had devoted almost 20 years to—depended on it. As the deep yanked at my sensory system like a gremlin inside my head, I had only one thought: What’s going to happen to me?

Between the Devil and the Deep Redux

WHEN I collaborated with Martin Robson to write about his battle with decompression sickness for Between the Devil and the Deep, I had no idea what it took to overcome a potentially life-changing injury. I’d managed to get through more than four decades without spending a single night in a hospital. It’s not that I hadn’t fallen out of trees as a child, or tumbled down a flight of 13 concrete steps that scarred my back, or sliced my hand open deep enough to see the bone, or cracked my head open on a garden step. It’s just that I seemed to have a durability that kept me on my feet.

So, on Monday morning, when I was wheeled into the private hospital room assigned to me by people who seemed to suspect a lack of response to treatment, I was defeated by hope and expectation. I’d fooled myself into thinking one treatment would put me back together again, but the ground beneath my feet still felt like it was trying to shake me down, and my vision remained unstable. I felt overcome with passivity as a nurse ordered breakfast for me, as a porter pushed me in a wheelchair between hospital departments for tests, and as I slept through my MRI scan.

I was wheeled back in the chamber on Monday afternoon for a second treatment using US Navy Treatment Table 9. Table 9 was introduced in 1999 to provide a dosing protocol for cases of incomplete resolution of DCS. I was taken down to the equivalent of 13.5 m/45 ft and told I would be given three 30-minute sessions of oxygen breathing.

Inside the chamber, there was nothing to do but read or watch television and I couldn’t do either. So, I closed my eyes, and my mind wandered. I thought about the SS Wisconsin and how much more there was to explore. I thought of everything I enjoyed about being underwater. I thought of the dive of that day. I accepted what had happened—as much as I could—but I still couldn’t quite believe where I was.

At the end of my first treatment, I had talked through the dive with the doctors. Scrolling through the log on my dive computer, I looked for a catastrophic event that could have explained the severity of my injury. I wanted to find a mistake—something I had overlooked underwater, something I could point the finger of blame at and say: ”Cowan, you idiot, look what you did!” I wanted to find something that said I didn’t have an undiagnosed medical condition that could change my life forever. There was nothing there.

During my third dose of oxygen, my vision suddenly stabilised. There was no warning, no gradual resolution; just an absolute change one would get from flicking off the power switch. One minute, I couldn’t focus, and the next, I could. Dennis Quaid appeared on the TV screen at the end of the chamber. I couldn’t hear him over the hiss of oxygen coming into my hood, but I could read the subtitles. The movie was Flight of the Phoenix and I tuned in just as Quaid was making his escape from the Gobi Desert on a makeshift aircraft rebuilt from the wreckage of his crashed plane.

The positive development inspired a new attitude toward my treatment, one I copied from Martin Robson. There is a passage in our book that resonated with me. It reads, “Like everything he did in life, Robson dealt with the here and now, what was in front of him. There was no point in trying to tackle the whole thing at once. After being ambushed underwater, he’d focused on what needed to be done to survive. One step at a time. Make it through one day at a time and figure out how to survive the next day when it was time.”

As I surfaced at the end of my second chamber treatment, I insisted on walking out of the chamber unaided.

Back in my room, I retrieved a notebook from the table beside my bed and, just like Robson, I wrote down everything I could remember about my condition. Then, just like Robson, I began to exercise. I paced the floor of the room. I repeated the test with my eyes closed. I tried walking heel-to-toe, as drivers must do during a roadside sobriety check, and I wrote down the results in the notebook (16 steps, wobbly). I stood on my left leg and timed how long I could hold my balance (20 seconds). I switched to my left leg (16 seconds). I switched back and tried to balance with my eyes closed (extremely difficult). I did it all again an hour later and noted the results. I assessed the stability of my vision and wrote that down: Looking to the right, stable, peripheral vision to the left blurred.

That evening, my wife Alison arrived at the hospital with fresh clothes and my toothbrush. She had been in the UK to celebrate her mother’s 80th birthday and was at the airport hotel on her way home when a friend called her.

“Mark’s okay, but he is in the emergency room,” he told her. “He had a problem after a dive.”

“Is he conscious?” she asked him.

“Yes.”

Alison couldn’t sleep after that and had an anxious wait as she flew back into Chicago. For 18 hours, she had no idea what was happening to me, but she knew it probably wasn’t good. When Alison finally walked into the room, I tried to give the impression I was okay, but I couldn’t fool her. I looked hurt, tired, and vulnerable.

Seeing her was the best part of my day, though. For the first time, I could think about something else as she told me about the surprise trip to see family and how she sat there just holding her mother’s hand after three years apart. Then we talked about where she could get some dinner, and we talked about health insurance. Eventually, we talked about the incident.

“I’m not going to ask if you plan to stop diving,” she said.

I appreciated her concern, but right then I didn’t know if I had a say in that.

Facing the Worst

I WAS discharged from the hospital after four days and five chamber treatments totalling more than 15 hours. I left feeling better than I had when I arrived, but I was not fully healed. The nystagmus had disappeared in my right eye; in my left eye it was “very slight.” Doctors decided there would be no more chamber treatments for me. My condition had plateaued. There was nothing more my doctors could do. Recovering, whatever that looked like, was up to me.

I went home. During the day, I sat on the sofa and watched television until Alison finished work. There was not much else I could do because going for a walk along the lakefront near my home strained my eyes and my head. I felt like I had just emerged from a bar after a heavy night; my body moved at one speed while my head lagged a second behind. The world seemed to race past me, but I was in limbo.

I had left the hospital with one number ringing in my ears. It was not the number on the insurance bill. That did hurt, but not as much as the figure on page 20 of the International Consensus Standards for Commercial Diving and Underwater Operations the doctors handed to me. More precisely, the number on the sixth row of table 2.4.10, “Return to Duty after Diving Related Incidents.” According to the table, I had suffered a “Neurological injury needing several treatment tables to resolve,” and that meant I had to wait four to six months before a return to diving. Beneath the table was a kicker: “Persistent neurological deficits following diving-related incidents are generally disqualifying.”

The details contained in the table sat heavily on my mind and made me angry as I stumbled about at home. It felt good to be angry, to vent, to cry, because if I wasn’t angry I would have to face my fears: the fear that the neurological deficit might be persistent, the fear that bubble in my inner ear was going to be the last word on my diving, that the cornerstone of my identity could be taken from me.

“I’ll be okay, I’m always okay,” I said to my wife each time I went diving. Well, I couldn’t say that now, because I wasn’t okay, and I was scared. Scared of what I may have done to my life; scared because I was too young to have put limits on myself. I was physically fitter than I had ever been, I was racing triathlons, and I was excited by the possibilities of exploration offered by my rebreather. I had big plans for the next decade. Would I now not get a chance to dive the Windiate, Kamloops, or the Norman? To dive caves again? To test myself in another triathlon?

What a gnawing sense of waste. What a shocking spell of self-pity.

The feelings came from the same place—the scarcity of information. My doctors had turned to the standards for commercial divers because there was little research relating to the recreational diving world to assist them. There was little in the medical literature on inner ear bends at all.

Inner Ear DCS?

Physician Andrew H. Smith was arguably the first to describe the symptoms of inner ear DCS in 1873 when he noted both extreme deafness and vestibular problems in caisson workers building the Brooklyn Bridge. After that, however, the condition was infrequently recorded as a discrete clinical entity. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the problem was reported in sport divers breathing compressed air.

Even then, studies suggested inner ear decompression sickness (IEDCS) is a low-incidence event. According to one report, IEDCS accounted for approximately 0.005% of cases. Another estimated the rate at close to 3%. One report found most victims were injured following dives which had pushed no-decompression limits, omitted decompression stops, or violated ascent rates. Another found the potential for isolated events to occur randomly during otherwise uneventful deep technical dives that had gone according to plan.

Then there was the contradictory information about the causal factors on IEDCS. “The biophysical basis for this selective vulnerability of the inner ear to DCS has not been established,” one report stated. Another report suggested the inner ear offered the potential for considerable supersaturation, and therefore possible bubble formation, during the initial phase of a conventional decompression. The environment allowed bubbles to grow until they eventually obstructed the labyrinthine artery. Since this artery was relatively small, there was a low probability for a bubble to enter it, another report indicated. Further studies, however, found a possible link between IEDCS and Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO), a hole in the heart which can allow gas bubbles to shunt from the arterial system into the venous system.

Nothing about an inner ear decompression sickness seemed clear, which revealed that the scientific community had a lot of ideas but not much definite information. I was confused and needed to go in search of answers for myself.

Aftermath Analysis

NINE WEEKS after suffering DCS, I was strapped into a chair in a pitch-black chamber at Aurora Physical Therapy, Neurotology & Audiology in Milwaukee. A set of infrared video goggles sat heavily on my head. The chair rotated back and forth at varying speeds, and the cameras in the headset recorded my eye movement. The test examined the components of the vestibular system all the way to the brain stem. It measured my vestibulo-ocular reflex—how my eyes and vestibular system interacted— and kept my visual field in focus while moving my head.

The rotary chair was one of several overlapping and complementary tests I had agreed to because I wanted to quantify the scale of the damage caused by the bend, and because I wanted to address the concerns of my doctor. I had fully recovered, but he was concerned about the dangers of my return to diving if my vestibular system had not fully healed (I might “suffer vertigo, lose my mouthpiece, and drown,” he said). And, he was concerned I might suffer a second bend in the fully functioning side of the vestibular system (I could suffer vertigo). He seemed particularly concerned that I would return to diving at all.

After the rotary chair had finished spinning and the results were collated, I moved to another seat and put on another pair of goggles. The video head impulse test examined the three semicircular canals in each inner ear. I was first asked to focus on a dot drawn on a sticky note placed on the wall in front of me. The audiologist stood behind me and he jerked my head in different directions. The video goggles captured my eye movement and analysed the time it took to return to the dot on the wall. I donned another set of goggles for the caloric test, which involved the blowing of hot and cold air into my ear to test for dizziness. Then electrodes were placed on my cheeks and neck and measured muscle response as loud sounds were played into my ear for something called the Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential Test which examined the upper and lower branches of the inner ear.

Once the tests were completed and the results were analysed, I met with my consultant, Dr. Aaron Benson. He was surprised by the findings. I think he was expecting to see global labyrinthine defects. Instead, he told me that almost everything was normal. Tests on my vestibulo-ocular reflex found just one area of minor deficit which revealed itself when my head was jerked over my right shoulder. That finding was confirmed by one of the other tests and indicated the possible site of my bend.

“What’s neat about you,” Dr. Benson said, “is that I can tell you exactly where [your initial insult] localises to a very specific area; it’s your right horizontal semicircular canal. That’s where your deficit was.”

“Functionally, you have demonstrated resolution of the initial insult. The question then is: ‘Why there?’ It is hard to say. It is possible you had a little nitrogen bubble right there that caused you all this mischief. That really does speak to the randomness of this.”

While the tests pinpointed the spot where I was hit, they revealed nothing of what had caused the incident. “Don’t ask too many questions,” one friend told me. “It will drive you nuts.” I couldn’t help myself, though, I needed to know.

I sent a download of my dive to Martin Parker, managing director of AP Diving, with the hope he could spot something. “It looks like a benign dive,” he emailed back.

He asked several questions. Did I use a heated vest? No. Did I do any gas switches? No. Was I dehydrated? Not that thought. Fatigued? Possibly, I’d had a long bicycle ride the day before. When I came off the bottom, did I have to swim up or was I neutrally buoyant? Neutrally buoyant.

The possibility of a PFO was raised again and the details of another medical paper, this one from 2017, were shared with me. The study reported a total of 62 divers with DCS. In all cases, divers were tested for PFO and 29 were found to have one. The highest prevalence was found in divers with cutaneous and vestibular DCS—my bend. It was suggested I get checked for a PFO to be on the safe side.

I couldn’t help but think that if I had a PFO, I would have been aware of it before now. Over the course of almost 20 years of diving, I had completed more challenging technical dives in more difficult conditions than I was subjected to when I suffered my injury. However, I was told that a PFO might not be an issue on every dive. That was why many divers could complete many deep, long decompression dives without incident only to one day get a bend on a moderate dive.

So, now I’ve been referred to a cardiologist to have a transesophageal echocardiograph to test for a PFO, and we will see what that means for my future. If the examination does not find anything, I will continue to be at a loss to explain the incident and the cause of the bend will remain a bit of a mystery. I hate mysteries, I’m never satisfied with a mystery; there’s always a reason, I just need to find it.

You can find Mark and Martin’s book here, “Between The Devil And The Deep.”

Dive Deeper

Alert Diver: May I Bend Your Ear? (2015) by Michael Menduno

PubMed: Inner ear decompression sickness in sport compressed-air diving (2001) by Nachum Z, et al.

J Appl Physio: Biophysical basis for inner ear decompression sickness (2003) by David Doolette and Simon Mitchell

J Appl Physio: Selective vulnerability of the inner ear to decompression sickness in divers with right-to-left shunt: the role of tissue gas supersaturation (2009) by Simon Mitchell and David Doolette

DAN: PFO and Inner Ear DCS (2014) by Petar Denoble, MD, D.Sc.

PubMed: Pathophysiology of inner ear decompression sickness: potential role of the persistent foramen ovale (2015) by Simon Mitchell and David Doolette

InDEPTH: Everything You Wanted To Know About PFOs and Decompression Illness, But Were Too Busy Decompressing to Ask (2021) by Doug Ebersole M.D.

Mark Cowan is a journalist with over two decades’ experience in newspapers and television. He spent twelve years on the police beat covering the war on crime for a series of newspapers in Birmingham, UK, and reported on the peace-keeping operations in war-torn Kosovo while embedded with the British Army. He has worked on a number of documentaries, including the BAFTA-winning Gun Number 6 which was inspired by his original reporting on the realities of gun crime in the UK. He has been a diver for 20 years, is a PADI Master Scuba Diver Trainer, trained to use a rebreather in 2012, and learned to cave dive while researching and writing the book Between the Devil and the Deep, One Man’s Battle to Beat the Bends with co-author Martin Robson. He is an avid wreck diver and is now based in Chicago, Illinois.