Education

Breaking Bad: How Do You Train Out Unhelpful Habits?

Sport psychologist and British tech instructor Matt Jevon offers instructors an evidence-based approach to help their students break those ingrained ‘bad’ habits that hold back their diving development.

by Matt Jevon

Header image courtesy of David Martin

How ingrained ‘bad’ habits can hold back divers’ development, and how as an instructor, you can help your student ‘break bad.’

I had the pleasure recently of teaching a father and son on an advanced nitrox and decompression procedures course. Dad was a very experienced diver of over 30 years, including senior instructor levels, the son was also experienced with a good number of dives in his five years of diving. Yet changing their diving foundations of buoyancy, trim and propulsion in order to have a base to build a technical qualification, proved to be a very different challenge for each. Thirty years of habitual 45-degree recreational diving where trim and propulsion were not a critical issue was a lot harder to overcome than it was for his son with only five years under his belt.

So what are habits? In psychology and in motor-skill learning, they can be defined as ‘automatic and highly entrenched behaviour patterns that resist change through retraining’

Good habits can be highly beneficial. They condition automatic responses in respect of appropriate cues, making skill execution and decision making faster, smoother, and more robust under stressful conditions. Unfortunately, bad habits are equally efficient at being implemented, and habits such as dropping knees or fins to a seabed, taking a deep breath before attempting a skill or even the biofeedback that suggests someone is flat whereas in fact they are still angled up, or feel head down whereas they are flat, is all a negative part of the ingrained bad.

How do we break these bad habits and instil new skills and decision making in experienced individuals with robust changes that won’t regress to 30 years on patterning?

Force of Habit

We have to understand what a habit consists of, how it is applied and what triggers the habitual behaviour to be implemented. All too often we as instructors just give the student the new and improved without understanding the degree to which the old ways are embedded. We actually need to help them break the old habit, before we can instil the new. Hence the phrase ‘Breaking Bad!’

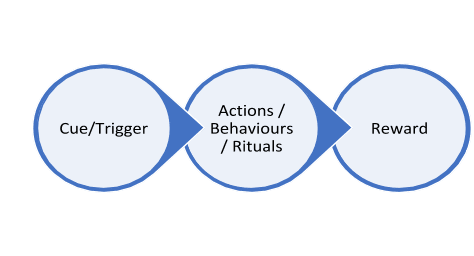

A habit consists of a cue or trigger, this begins a ritual / behaviour or sequence of events (timings/actions/steps of both thinking and doing in a pre-learned order) and ends with some sort of feedback or reward. A good reward will provide that nice little dopamine hit, even if rewarding a bad habit e.g., comfort eating or throwing the alarm clock out of the window.

So, step one to breaking bad is identifying the cue or trigger. Easier said than done. If the habit is sufficiently embedded in the autonomous or subconscious, and the person may not know what the cue or trigger is. As an instructor, you can observe possible behavioural cues, but not cognitive or emotional ones. Therefore, the debrief really helps here, especially if you can get the student to replay the moments before the bad habit was exhibited in a rich guided imagery replay.

A quick but strong point: NOT with visualisation. Visualisation is only one solo element out of many senses, plus thoughts and emotions that are fully used in imagery and is a sort of ‘lightweight’ way of mentally rehearsing and recalling. Learn to use and apply imagery in fulltouch, taste, feel, smell, see (internally), and think.

Going through guided imagery this way should help the student identify the actions, thoughts, and/or feelings that trigger the behaviour. It may need to be dragged up from deep in the subconscious and cannot be glossed over by, ‘I’ve always done it that way’—a concept as flawed as ‘human error’ or alcohol-free beer.

Once the cue/trigger is identified, then leave it in place. Trying to change this will be a real uphill struggle. Instead, replace the ritual or actions that follow the cue with something that leads to the desired outcome. For example, feeling under stress due to task load as a cue, current ritual/action, drop knees. Instead, tighten glutes and head up. Reinforce with thoughts and cues relying on self talk e.g., solid base, (trim, buoyancy) before starting skill.

Then this change must deliver a reward. The key here is that the reward must come from and be recognised by the person. I don’t care how big and cheesy you make your congratulations handshake (please stop that), the reward must link to the task. Now, this doesn’t mean you should get the students to carry a packet of biscuits around in the drysuit pocket. Actually, it needs to be something that triggers that happy hit of dopamine.

For some, that will be the success of executing the drill, for others the relief of a successful execution (Need to achieve vs. fear of failure motivations). The key is to go back to the guided imagery session. Work through the, ‘How do we know what good feels like?’ imagery and then ‘What does success feel like?’. Focus less on the mechanics at this stage, and more on the thoughts and emotions.

Teaching a New Skill

Teaching and coaching the new skill set can follow more traditional teaching, instructing and coaching practices, and guided imagery to help it become a habit. If you don’t know the difference between these terms then you need to. It’s critically important in developing learning to have a definition and understanding of whether you are teaching, coaching, or instructing. It should be a deliberate choice to apply one of these approaches and understand how that changes your role and delivery. Another article maybe.

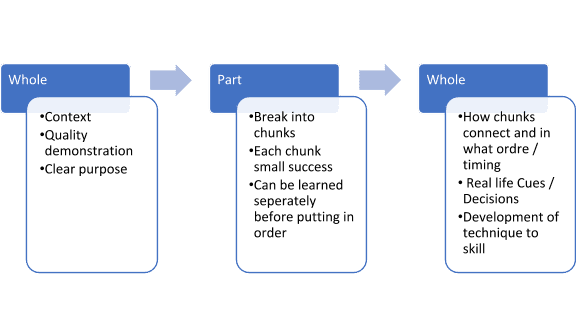

The pure skill acquisition (motor learning – technique – skill) should follow the pattern of whole, part, whole, based on the well documented and highly effective chunking approach. So you demonstrate the whole skill, then break it into discrete parts for the student to master, then bring those parts back together as a complete whole. The chunks are the small and discrete ordered steps or elements of the movements that the student learns and practices.

Starting with simple movements, developing to complex, and eventually becoming a skill by being able to execute the whole smoothly and quickly even if under appropriate stress. Until they can do this it’s not a skill, it’s just a technique. So, as an example, consider a bailout drill. In a very short period of time a diver can learn the techniques of bailing out, find and identify bailout reg, close loop mouthpiece, jump onto bailout reg and change computer. However, when presented with Wet Notes containing an exact replica of the handset readouts showing a PO2 of 2.8, can they make a bailout decision and execute those techniques smoothly and flawlessly? If so, it’s a skill. If not, the instructor hasn’t finished their work.

Caveats

Something to guard against is when you try to force the changes without breaking the existing bad habits. This can lead to reinforcement of a belief by the student of something known as ‘learned helplessness’. This is where failure after failure in breaking the bad habit leads to a belief that they ‘just can’t do it’ or they ‘are not ever going to be good enough’.

The trick here is to lay out realistic expectations and ensure your chunking is sufficiently broken down to allow progress towards the whole in smaller, easier parts. The other outcome is a mongrel bred of the new habit and the anchored parts of the bad habit.

You may consider yourself a genius instructor if you can correct a bad habit in a two-to-three day course. However, you would be delusional if you did. The student can probably execute the good habit in response to a new and fresh cue you have given them, but you haven’t broken the old one. As soon as the original trigger emerges, the old actions will follow. This becomes particularly evident when you progress from skills-based training, to scenario-based training, where you as a good instructor recreate real life scenarios and cues, layering decision making over the top of the motor skills.

If you have a new student with no bad habits, then you will be up against the inexperience barrier, so applying context and developing decision making in context will be harder. You should be very careful though not to instil bad habits from the start. Don’t allow a student to do multiple technique repetitions, definitely not of poor movement patterns and particularly in response to inappropriate cues. Be clear what cues the student should first recognise, then help them choose and respond to the appropriate ones and filter out the inappropriate.

For example, a really inappropriate cue is the instructor ‘do this skill’ signal. The real cue you want to embed and attach to multiple repetition is something that would actually be seen by the diver in a real life scenario. For example, my students will only see the bailout signal on the very first dive where I teach the technique. After that, the move from technique to skill is always associated with a realistic and relevant cue.

By the way, the exact same principles apply to breaking any bad habit, health wise, eating or smoking, etc. The trick is recognising the cues and critically recognising the reward. Success will only follow if you can replace the ritual/behaviours that follow a cue with the new desired behaviours and crucially that they give at least an equivalent reward and preferably a greater reward.

I’m sorry if this article didn’t cover buying a caravan and a ‘how to’ guide to, well, you know. I do hope it makes you reflect on the order and structure of your courses, the need to spend time understanding your students’ habits, good or otherwise, in order that in conjunction with that student, you can truly break bad!

References

- Fig 1. Adapted from Durhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. New York: Random House.

- Fig 2. Adapted from Martens, R. (2012). Successful Coaching. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Dive Deeper

- Hardwick, R. M., Forrence, A. D., Krakauer, J. W. & Haith, A. M. Skill Acquisition and Habit Formation as Distinct Effects of Practice. bioRxiv (2017). doi:10.1101/201095

- Schmidt, R.A., Lee, T., Winstein, C. Wulf, G., Zelaznik, H.N. (2018). Motor control and skill acquisition. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Il.

Matt Jevon, M.Sc. F.IoD is a Full Expedition level Trimix and Cave instructor on OC and CCR with TDI and ANDI. He is the JJ-CCR and Divesoft Liberty Sidemount instructor and dealer for Ireland. Matt’s personal diving has included cave exploration in the Philippines, wreck projects in Croatia and Ireland, as well as being one of the inaugural dirty dozen in Truk! Matt has held accreditations as an interdisciplinary sports scientist, sports psychologist with BASES, and was a British Olympic Registered Strength and Conditioning Coach and invitee on the Olympic Psychology Advisory Group. Matt works in high performance business as a board advisor and non-exec, high performance sport, and is a partner in South West Technical Diving in Ireland. www.swt.ie and writes the Facebook page, Psychological Skills for Diving