Community

Building Community Through Project Diving

By Guy Shockey. Photos courtesy of Andrea Petersen

Several years ago, I wrote an article for Global Underwater Explorers’ membership magazine QUEST, titled “Passion, Partnership and Exploration: GUE and the local community.” In that article I talked about the importance of linking your passion to a purpose and keeping those two concepts connected.

I suggested that those divers who did this would have a lifetime of adventure in the underwater world. Before I had even heard about Simon Sinek and his question of “What is your why?” I wrote that if you didn’t ask yourself why you learned to dive and then find a way to continue to feed that “why,” your diving interests would wane.

In that article I also wrote that there were more and more GUE projects happening all around the world and predicted that “as GUE grows and matures, these opportunities will increase, and the concept of a global approach to exploration projects will become more and more common.” At the time, this seemed like a natural growth aspect of GUE, and I was very excited to learn about the new Project Diver curriculum, which is exactly that! I should have bought a lottery ticket the day I wrote that article because it seems like I was looking into a crystal ball!

I will make another prediction now, and that is that with the introduction of GUE’s new Project Diver program , we will see more and more GUE projects pop up around the world. There are always the pinnacle projects that capture our attention and motivate us, but now we are helping provide the tools that GUE divers need to start their own projects! For many of us, this will help feed our “why,” and will work to encourage our involvement in diving. And, it will result in significant growth in the number of opportunities for us to connect our passion with a purpose.

While many of these projects will be generated by the various GUE divers themselves, there are also other ways to jumpstart projects. I touched upon this in the same Quest article, but because It’s such an important topic, and our Project Diver course is gathering momentum, I thought it would be fortuitous timing to revisit an opportunity that likely exists in many locations.

Teaming Up With Scientists

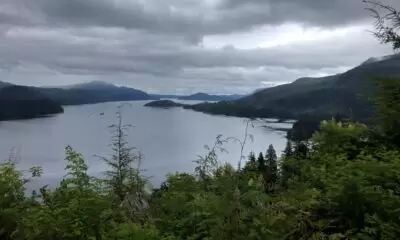

Through a series of fortuitous decisions, I am lucky to live and dive on Vancouver Island, which is located off the West Coast British Columbia, Canada. Vancouver Island is essentially a large pinnacle protruding out of the Pacific Ocean, over 2,000 meters in the middle, and it is nearly bisected in several places by inlets that are not unlike the Fjords of Norway. Because of this extensive shoreline, it has a significant maritime history and tradition. The waters can also be quite treacherous, and I have been told by experienced sailors that the waters here are some of the most challenging sailing conditions in the world. Challenging conditions coupled with a lot of shipping means that our coastline is littered with over 5,000 shipwrecks.

For someone interested in marine archaeology and exploration, Vancouver Island is a treasure chest of opportunity. And it just so happens that there is already a group on the island with a long pedigree of recognizing this opportunity.

The Underwater Archaeology Society of British Columbia (UASBC) was formed in 1975, and it is one of the most productive avocational underwater archaeology groups in the world. After its formation, the UASBC began a methodical program of surveying wrecks off the coast of British Columbia and in the waters surrounding Vancouver Island. They have been incredibly successful in this and have published numerous books and articles on British Columbia’s maritime history. Along the way, they have developed some very good relationships with several organizations such as the Canadian Hydrographic Service and Parks Canada and have allowed the UASBC to provide much of their survey and research information to the Government of British Columbia.

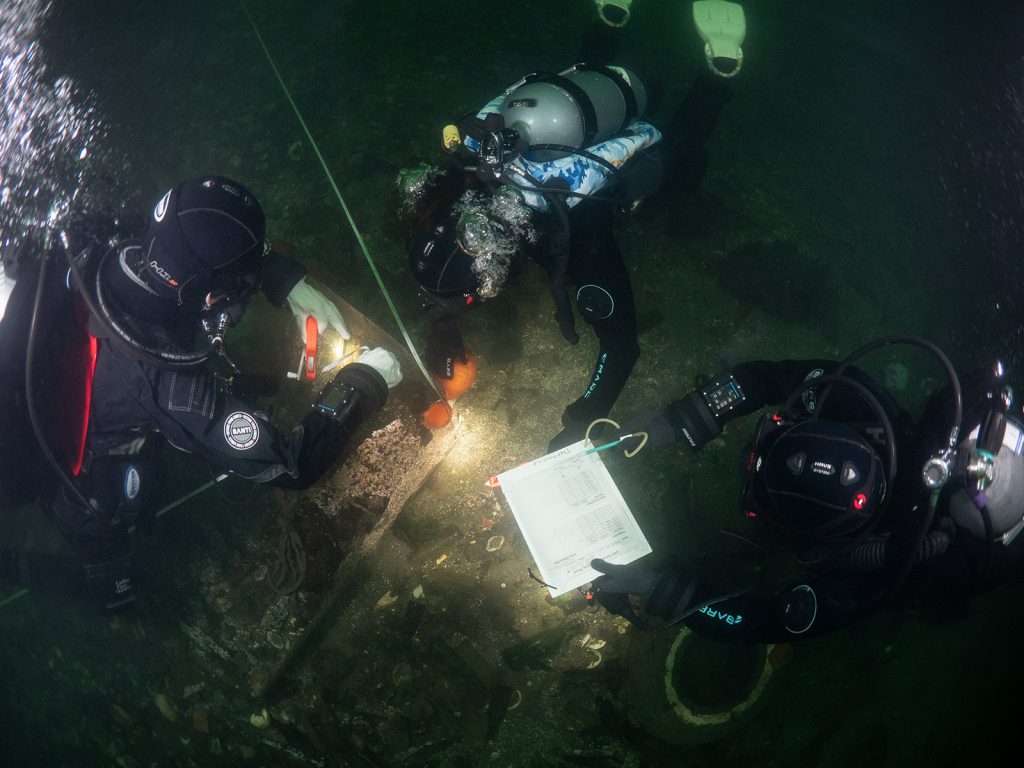

Nearly ten years ago, a group of technical divers on Vancouver Island began working with the UASBC to help document the wrecks that fell outside of the UASBC’s primarily recreational focus. There are historical records and underwater search telemetry from tools such as side-scan sonar and multi-beam sonar, which map the seafloor, but there is still no substitute for actual first-person observation that can provide sketches, photo, and video records. Because the UASBC had done most of the work available in recreational depths, until technical divers were part of the research projects, there was a limit to further new project work.

For a while it seemed like the future was going to be very bright: there was a group of committed technical divers with a passionate wish to. to explore, and the UASBC had the targets that needed exploration. There was some collaboration, but not as much as could have been the case, and when one of the divers in a leadership role became more involved in their non-diving career, the relationship hiccupped for a short time until a few other local GUE divers took up the task of building this relationship.

This time around, things have really taken off! Part of it is, no doubt, related to the growth in the size of the local GUE community and likely also because there are at least 15 new JJ CCR divers with a passion for exploration in our group, and another 15 just south of the border in the Seattle, Washington area. We also have two of our local members participating in the UASBC on their board of directors. I’d say we are firmly committed to this relationship, and we are already starting to see some amazing results from this collaboration.

The UASBC has also been energized by our relationship, and they were spurred on to write a new “Underwater Archaeology for Divers” program that is specifically tailored to our waters. This has jumpstarted even more interest in UW archaeology and, at last count, I think we have produced at least 20 new graduates, many of whom are also GUE divers.

Our GUE community has been part of recreational depth surveys and, in this past fall, we were the first to identify the wreck of the SS Admiral Knight and we are working on confirming the identity of a historically significant wreck off the waters of Gambier Island. As I write this, we also have a UASBC member recreational charter booked for late November, which allows GUE and non-GUE divers to get to know each other and dive together.

We are also starting to flesh out our 2023 project and exploration diving schedule, and based on our successes in 2022, there will be multiple opportunities for GUE members around the world to participate in our projects. They will be published on the GUE website in the projects section, and we encourage GUE divers to participate to the level of their training and capacity.

Our relationship with the UASBC is a function of serendipity and a little bit of luck, but there also exists similar opportunities around the world for GUE divers to work with existing groups to the benefit of both. This results in a synergy of purpose and, when the smoke clears, provides an opportunity for GUE divers to engage their “why.” As I wrote, “if you can identify an existing organization that shares similar goals, it can be easier to combine skill sets and resources for the benefit of both.” I suggested that you take a look around your community and see what resources exist. It’s very likely that much of the heavy lifting for starting up an exploration project has already been done. At the very least, you can jumpstart your project and build on the work of others.

When I wrote my original article, I mentioned that it was likely that many of these groups would be unfamiliar with GUE. I think this has changed a lot in the last 10 years, and I suggest that most of these groups would now be familiar with our organization. Ten years of tireless effort and work has made quite a mark in the underwater exploration world! Now, with the addition of the new Project Diver program, I expect our initiatives will grow.

I start every class by saying that this is a terrific time to be a diver, and there are more opportunities to connect passion with purpose than ever before. Good luck combining your community efforts with those of existing exploration groups and happy adventures!

Dive Deeper

InDEPTH: Introducing GUE’s New Project Diver Program by Francesco Cameli

InDEPTH: How to Become an Explorer: Passion, Partnership, and Exploration by Guy Shockey

Guy Shockey is a GUE instructor and instructor trainer who is actively involved in mentoring the next generation of GUE divers. He started diving in 1982 in a cold mountain lake in Alberta, Canada. Since then, he has logged somewhere close to 8,000 dives in most of the oceans of the world. He is a passionate technical diver with a particular interest in deeper ocean wreck diving. He is a former military officer and professional hunter with both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science. He is also an entrepreneur with several successful startup companies to his credit.