Latest Features

Calculated Confusion: Can O2 Get You High?

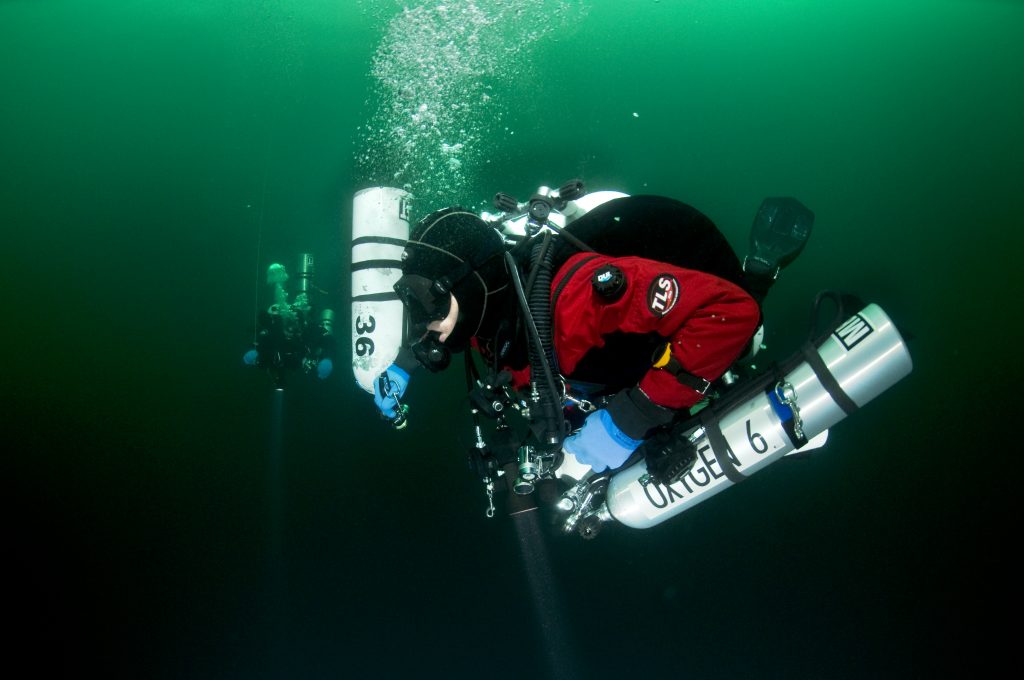

Anyone who’s dived to 30 meters on nitrox (we don’t do air here!) is familiar with what Jacques Cousteau eloquently termed “rapture of the deep”—the result of breathing high partial pressures of nitrogen. But what about the oxygen? As you may know, there are some convincing arguments that oxygen should be considered narcotic at depth as well, but there are also many qualifiers, anecdotes (ever feel narc’d on your 20-foot O2 stop?), and a broad swath of research and nuance that casts some doubt. Diver Alert Network’s Reilly Fogarty teases out what we know and what we don’t. Mind your ENDs!

by Reilly Fogarty

Header image by Sean Romanowski

Hyperbarics is a tricky field to study — gas laws sometimes behave like suggestions, the effects of high-pressure gases in the body are highly subjective, and decades of research often end in what amounts to an educated guess. Our understanding of narcotic gases is a great example of this: we know a little about increasing partial pressures of nitrogen decreasing our motor function and cognitive ability, and a bit about some gases like helium ameliorating those effects, but not much else. The specific mechanisms of action, variability through human anatomy or interactions with other gases, and the range of those effects at various depths are the stuff of theory rather than proven science. There are some convincing arguments for the treatment of oxygen as a narcotic gas, but the qualifications are many, and a broad swath of research and nuance casts everything we think we know into doubt. Here’s what we know so far, as well as some best-practice recommendations. Understanding the narcotic effects of oxygen is by no means a clear-cut situation.

A Primer on Narcosis

Before discussing narcosis, it’s important to cover what we know already. Narcotic gases (any gases that can cause narcosis, including nitrogen, argon, etc.) have a wide range of effects, all affected by depth. The general consensus is that these gases likely interfere with the release or uptake of neurotransmitters in the body or alter the postsynaptic response from those transmitters. Greater partial pressures of some gases increase this effect, which is why we see increased narcosis as we descend on a gas containing nitrogen. In short, much like the gases used for surgical anesthesia, common diving gases can interfere with the communication pathways in our body.

The effects of these gases are understood by the Meyer-Overton rule, a holdover from anesthesia research in the early 1900s. *Updated: The rule predicts that the anesthetic potential of a gas is directly related to its lipid solubility (i.e., a gas that can be absorbed effectively by fatty tissue will be more narcotic than one that cannot) and ranks gases by that solubility. Helium exhibits extremely low lipid solubility and correspondingly little narcotic potential according to this rule, and this holds true to experience. WAS: The rule predicts that the anesthetic potential of a gas is inversely related to its lipid solubility (i.e., a gas that can be absorbed effectively by fatty tissue will be less narcotic than one that cannot) and ranks gases by that solubility. Helium exhibits extremely high lipid solubility and correspondingly little narcotic potential according to this rule, and this holds true to experience. The effects of oxygen, however, appear to be significantly more complex.

Note: These units are permeability coefficients. A larger number represents a greater energy required to pass the same quantity of gas through a membrane or lipid tissue, indicating decreased solubility. Gases with smaller permeability coefficients (helium, for example) are more soluble and can permeate barriers more easily while gases with a larger permeability coefficient (like oxygen) are less soluble and require more energy to pass through a barrier. More information on gas solubility and permeability in specific tissues can be found here.

Working solely from the Meyer-Overton rule, it would appear that oxygen should cause significant narcosis — it has twice the lipid solubility of nitrogen and thirty-eight times that of helium. Comparing just the lipid solubility of nitrogen and oxygen, it appears that saturation with oxygen would not only cause narcosis but would also result in stronger symptoms than those caused by nitrogen. The aptly named, Does Oxygen Contribute to the Narcotic Action of Hyperbaric Air?. a paper by hyperbaric researchers from 1990, attempted to confirm just that hypothesis. Researchers compared motor skills and mental performance with participants exposed to air and normoxic nitrogen and oxygen mixtures at 6, 8.5, and 11 bars ambient pressure. They found impairment of up to 40 percent at the highest pressures of all gases, but participants exhibited the same impairment on oxygen as gases with higher partial pressures of nitrogen. Their conclusion indicated that oxygen did not ameliorate mild narcosis and should, therefore, have some narcotic properties.

A Case for Oxygen

A similar paper from a little more than a decade before found the same results. A rise in the partial pressure of oxygen to 1.65 ATA gave similar narcotic effects as a rise in the partial pressure of nitrogen to 6.3 ATA, or an end-tidal pressure of CO2 or 10mmHg. Again, these researchers came to the conclusion that while the specific contributions to narcosis from oxygen could not be exactly measured, it did appear to contribute to the narcosis of divers.

There’s an argument for the sake of safety here too. Oxygen may be narcotic, so by calculating our equivalent narcotic depth (END), by including oxygen in the calculations as we would nitrogen (more on how to do that later), we give ourselves an extra margin of error. If oxygen is, in fact, narcotic, we’ve planned for its effects at depth, and if it isn’t, then the worst thing that happens is we have a little less narcosis than expected.

Narcotic Nuances

When I said hyperbarics was a tricky field to study, I meant it, and not just because of the complexity of the issues involved. Understanding the effect of oxygen in the body is an incredibly nuanced balancing act that involves attempting to apply our limited understandings of oxygen metabolism, neurotransmitter function, metabolic dysfunction, inflammatory responses and more, all in the application of something that in the end will be almost entirely subjective. There are a few notable issues with the presentation of oxygen as a narcotic gas, and they’re easiest to work through in pieces:

Meyer-Overton

Rules were made to be broken and Meyer-Overton is no exception, despite holding mostly true for more than a century. Not only does it lack a specific mechanism of narcotic action, but there are some explicit exceptions to the rule. It should be noted that even these exceptions are the source of some controversy, but it’s widely believed that several anesthetic gases work in exception to the Meyer-Overton rule, specifically anesthetics with long alkane chains in their structure. Some of these gases exhibit dramatically lower potency than would be expected based on their lipid solubility, and we have no way to know whether oxygen is one of these exceptions to the rule or just another narcotic gas.

Environmental Concerns

The environment we’re concerned about, primarily deep open- or closed-circuit diving has a long list of restrictions for the application of oxygen. As divers, we carefully plan our exposures to keep oxygen in a narrow range of partial pressures while diving. This careful control of the PO2 of our gas means that we’ll never see a PO2 greater than 1.6. While a ride in a hyperbaric chamber may exceed that threshold, it’s unlikely to see in the water and brings to light another question — if oxygen is narcotic, at what partial pressure do you see the effects? No study available on the subject is able to define either the PO2 at which oxygen begins to have a narcotic effect or to even strongly correlate pressure and narcosis on oxygen alone.

Compounding this confusion is the fact that oxygen is a gas that we constantly metabolize. Even if we were to breathe similar amounts of nitrogen and oxygen during a dive, the metabolic processes required to keep us alive and well constantly consume some of that oxygen. How much oxygen is consumed and at what rate is a complicated answer based on individual physiology and what a subject is doing at any given time, making it even more difficult to isolate the effects of oxygen from the metabolism of inspired gas. Until now, our understanding of narcosis has relied on our ability to estimate the partial pressure of nitrogen in our gas, but once oxygen enters the mix, a whole host of new variables become important to consider. While it’s true that we can estimate the effects of the gas based on theories and the research we do have, it’s not enough to definitively say that oxygen is a potent narcotic.

Putting It to Practice

Academic review is one thing, but putting a new concept to practice is what brings it home for most divers. Here’s how you can calculate END with oxygen included as a narcotic gas (the most common decompression planning software also offers an option for this in their calculations):

(Depth + 33) X (1 – fraction of helium) – 33

Because oxygen and nitrogen are considered equally narcotic, END can be calculated using the total of a gas minus the fraction of non-narcotic helium.

Best Practices

Discussions of narcotic gases rarely provide rewarding moments of discovery. What we have as divers and as an industry is a best guess that indicates that oxygen is likely narcotic, but we don’t know what the mechanism of that narcosis is, nor do we know how potent the effects of oxygen are. The issue is deeply nuanced and requires some careful consideration before arriving at a conclusion, but your mental tribulations shouldn’t ruin your next dive. As a dive safety organization, Divers Alert Network has an interest in promoting safe diving practices, and the results in this case are promising and present little additional risk. Calculating your END with oxygen as a narcotic gas is a safe and conservative practice until researchers tell us definitively that it’s non-narcotic. Aside from a slightly higher gas bill there’s no downside, but you might just be safer for it.

For more information on narcotic gases and advanced dive planning, visit DAN.org or contact the author at [email protected].

Works Cited:

1. Scuba Diving in Safety & Health by Chris W Dueker, MD

2. Diffusion Coefficients for Gases in Biological Fluids and Tissues

3. DOES OXYGEN CONTRIBUTE TO THE NARCOTIC ACTION OF HYPERBARIC AIR?

4. Roles of nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide in compressed-air narcosis

5. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN CRITICAL ANAESTHETIC DOSE AND MELTING TEMPERATURES IN SYNTHETIC MEMBRANES

Reilly Fogarty is a team leader for risk mitigation initiatives at Divers Alert Network (DAN). When not working on safety programs for DAN, he can be found running technical charters and teaching rebreather diving in Gloucester, MA. Reilly is a USCG licensed captain whose professional background includes surgical and wilderness emergency medicine as well as dive shop management.