Community

Can Diving Help Heal Trauma and Abuse?

April is Sexual Assault Awareness & Prevention Month in the United States. To honor those impacted, Holly Gibbs presents InDEPTH readers with a true story of sexual assault and trafficking that offers some insight into how diving has helped some survivors, including herself, return from the dark places that abuse took them. It’s a profile in courage you will surely find inspiring.

by Holly Gibbs. Images courtesy of Holly Gibbs.

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of abuse and violence. If you’re seeking support from sexual trauma, help is available. In the U.S., you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit www.rainn.org/resources.

In 2005, I was in my twenties living in Southwest Florida and working as the technical director of a microbiology laboratory. Despite spending very little time outside or on the water—other than drinking rum runners at the beach tiki bars—my boyfriend at the time had signed us both up for an open water certification class as a surprise gift.

This class was one of the hardest things I had ever done physically and mentally. What I didn’t know at the time was that, as a survivor of child sex trafficking and other trauma, I had a higher risk of suffering from panic and anxiety disorders. As a first-time diver, this significantly impacted my stress level during the course.

I knew I had to dig deep if I was to complete this class. And I did.

April is recognized as National Sexual Assault Awareness & Prevention Month in the United States. Although this may be a difficult topic for many readers, sexual violence affects many people in the diving community. Every 68 seconds, an American is sexually assaulted; and every 9 minutes that victim is a child.1 Sexual violence impacts people of all ages, races, and genders.

Unfortunately, I went on only a few more diving trips after completing my first course. I saw lobsters in the Florida Keys, collected sharks’ teeth in Venice, and explored an underwater cave. As I got older though, my stress and anxiety worsened, and I no longer pursued scuba diving. That is, until I was inspired by another survivor of sexual violence who is also an expert on trauma.

Meet Emily Waters, LCSW, MPA, PhDc

Emily Waters is a mental health and medical professional—she’s also a survivor. She decided to share her inspiring story to help raise awareness about sexual violence, highlight how resilient victims can be, and explore how she found long-term healing in scuba diving.

After graduating college in 2012 with a Master of Social Work and a Master of Public Administration, Emily Waters wanted to celebrate, so she took a month-long trip to Australia and New Zealand.

In Cairns, Emily signed up for a Discover Scuba Diving trip on a whim. “I was absolutely terrified,” she said. “I was extremely claustrophobic and not keen on the idea at all. I thought it would set off a huge panic attack. But I was on holiday in Australia at the Great Barrier Reef and decided to give it a shot. I fell in love immediately.”

After this first experience underwater, Emily continued to pursue diving trips around the world. “There is a peace and serenity when all you can hear is the bubbles you make and the sound of the wildlife,” Emily said. “That quiet and sacred place became my sanctuary—and it continues to be. There is a feeling of relief and surrender when you are allowed to share this space beneath the surface, watching sharks, giant turtles, and a myriad of flora and fauna.”

Before discovering this magical world, however, Emily had lived a lifetime of mayhem.

Emily’s Story

“I started life as a premature, safe surrender baby and spent three months in the NICU,” Emily explained. “I was adopted, and my family lived in constant chaos. My adoptive mother was severely mentally ill. She displayed symptoms of paranoia, prosecutorial complex, and lack of empathy for others. When she was up and about, our home was filled with violence. I would later understand that she had schizophrenia, among other disorders.”

Studies show that people who experience trauma in childhood—particularly abuse, neglect, parental separation, and substance use or mental health disorders in the home—are at a higher risk of experiencing negative health outcomes later in life, including ongoing exposure to violence and other forms of trauma.

Unfortunately, this was true for Emily.

By age fourteen, Emily was staying away from home as much as possible, working full time as well as attending school. She says that when she left home at age seventeen, she had no plan.

“I began to work more and more, and I took a few classes at a local college,” Emily explained. “I was using methamphetamine to stay up for 22 hours straight five days a week for two years.”

Emily says she felt like she was finally gaining some footing, and then, at age 18, she experienced a violent sexual assault. While out with friends, she got separated from her group.

“I was raped, beaten, and left for dead,” Emily explained. “I crawled up from the ditch where I had been thrown and knocked on many doors until I found someone who would answer. They left me standing bloody and mostly naked on their doorstep. This is how I lost my virginity.”

After this traumatic experience, Emily continued to survive on her own. She worked, attended school, and coped with her post-traumatic stress symptoms by using alcohol and other substances. She was soon targeted by human traffickers, including members of a violent organized criminal enterprise who used beatings, death threats, and sexual violence to control their victims, including Emily.

Human trafficking is a form of violence in which a person is forced—via violence, fraud, or coercion—to provide labor, services, or commercial sex. Commercial sex describes any situation in which something of value is exchanged for sex, such as money or drugs.3

Emily’s story is dark and tragic. But where there is trauma, there is often resilience.

The Road to Recovery

Emily is a survivor. In 2001, with help from a friend, she managed to escape. “I simply disappeared,” Emily explained. “I bought a plane ticket to another state, and after numerous harassing phone calls, I changed my number. And the traffickers never found me.”

Emily spent several months in a treatment center for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This included three months in inpatient care and four months in a sober living environment. It wasn’t easy, but Emily was determined to succeed.

“During the time I was trafficked, I lived in a constant state of panic and hypervigilance,” Emily explained. “My experience was a classic form of complex trauma. As part of my treatment, I worked with trauma therapists who used eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, brainspotting, and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy as techniques to work through my experiences and help with diminishing flashbacks and triggers. These techniques also helped me to understand that the abuse was not my fault.”

After several months of homelessness, recovery and healing efforts, and working several jobs, she was able to put a security deposit down on an apartment and pursue a career in trauma therapy.

Healing Under the Sea

Back to Australia in 2012, where Emily celebrated graduating with two master’s degrees and discovered her passion for scuba diving. After returning to the States, Emily completed her open water certification.

At the time, Emily was living in California and working in South Central Los Angeles as a paramedic. She explained that, as one of only two female paramedics in the region, and the only one who was able to speak Spanish, she was constantly requested during her 24- to 48-hour shifts.

This high level of intensity followed Emily for the next ten years—from California, to Texas, to New York—where she provided around-the-clock care to survivors of sex trafficking and administered training and technical assistance (TTA) to other professionals such as law enforcement officers, legislators, and health care workers. Emily continued diving internationally, but she knew she wanted to dive more frequently.

“When I worked as a paramedic,” Emily explained, “the phone would ring at any time day or night. Later, when I moved to New York, I continued to be on-call 24 hours a day seven days a week, unless I was out of the country. And then, after I was provided with a satellite phone, I was expected to be on-call even when I was traveling. I was burning out.”

Emily found a local dive shop in New York where she began diving weekly. She quickly completed her advanced open water certification and other specialty classes.

“While the conditions in New York don’t provide the clearest visibility,” Emily said, “I was able to do further training, gain more confidence underwater, and most importantly, have at least a few hours per week when my cell phone was locked in the glove compartment. I craved that time away from the noise; I just needed quiet. Oddly, when people ask me why I started diving and training, my first response is usually, ‘No one could call me while I was underwater.’

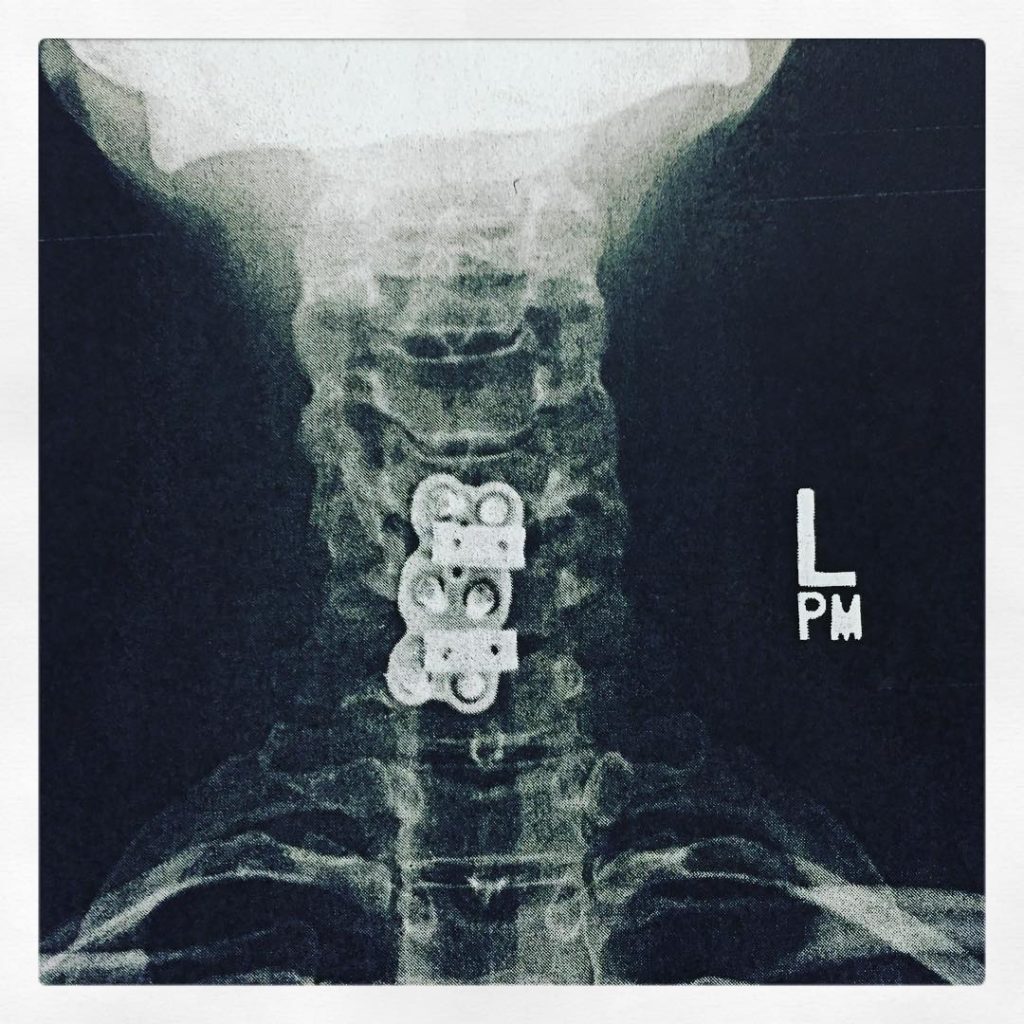

Although Emily found the respite and continued healing that she needed with local dives, she struggled with the challenging water conditions in New York. Like many survivors of violence, Emily faced long-term physical health effects which affected her ability to dive. For example, Emily explained that when she was a victim of sex trafficking, she sustained fractures to three vertebrae in her neck that later required reconstructive surgery.

“As a result of the surgery, I’m unable to look up and down,” Emily said, “I can only move my head from side to side. This prevents me from maintaining a horizontal profile underwater, which is considered the proper posture. So, when I’m diving, I’m typically more vertical than horizontal. Otherwise, I can’t see what’s around me, which is a safety issue.”

Emily explained that she had to modify diving protocols and equipment to accommodate.

“I can’t walk around with a BCD or tank on my back,” she said. “Divers typically walk into shore or jump off a boat this way, but I usually can’t do this because of the strain on my neck and shoulders. So, I basically chuck my equipment in the water and then jump in to go get it.”

Emily laughed, “This freaks some people out, especially in choppy water, but I always explain that I’m good; I’ve got this.”

As Emily’s healing journey continues, she still works with survivors of violence and provides TTA; however, she left the situation where she was constantly on-call.

“I was pouring everything I had into helping others,” Emily said, “I wanted to help others find the path from victim to survivor, but toward the end I was giving up too much of myself. I need to ensure that my own physical and mental health is in a good place.”

Diving remains a source of peace for Emily—and the underwater world a place of healing. “Scuba diving was the first thing I can recall that was just mine—where I could just feel free and enjoy myself.”

Today, Emily continues to dive on a regular basis both in the States and abroad. She recently completed her Divemaster certification in Bonaire and is continuing an instructor course in New York. Emily’s goal is to specialize in adaptive diver training so that she can help divers with disabilities or histories of trauma who must adapt diving procedures, techniques, or equipment.

Emily is an inspiration to survivors of sexual violence across the world, including myself. It’s been over 15 years since my last scuba diving trip. However, after watching Emily’s adventures on social media, I’m ready to get back in the water. I reached out to my local dive shop to enroll in a refresher course, and I’m looking to book a scuba diving trip soon.

To learn more about how you can raise awareness, prevent sexual assault and violence, and become an ally for victims and survivors, visit www.rainn.org.

- Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), About Sexual Assault, www.rainn.org/about-sexual-assault (accessed February 26, 2023)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study, www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html (accessed February 26, 2023)

- United States Public Law 106-386: Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. Includes the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA).

Dive Deeper

DescentProject.com: Descent Dutch ice freediver Kiki Bosch dives in the world’s coldest waters without a wetsuit as therapy for the trauma of sexual assault, and to inspire (2020) others.

Into The Planet Podcast: Diversity, Equality and Inclusion in Scuba Diving by Jill Heinerth & Robert McClellan (MAR 2023)

Diver: Sexism: Alive and well in scuba diving by Jill Heinerth (2015)

Holly Austin Gibbs graduated Richard Stockton College of New Jersey in 2000 with a Bachelor’s in biology. While working in Southwest Florida as the technical director of a microbiology laboratory, she received her open water certification. In 2014, Holly published a book called “Walking Prey: How America’s Youth are Vulnerable to Sex Slavery” (St. Martin’s Press), in which she shares her experience as a victim of child sex trafficking. After traveling across the country and speaking on the topic of sexual abuse for many years, Holly is looking forward to returning to scuba diving. Holly and her husband, Ben, now live in Richmond, Virginia, with their chihuahua, Bumper.