Art

Limestone, Light and Water

These are the elements that British expat photo-alchemist Tom St. George transmutes into pure visual gold.

By Tom St. George

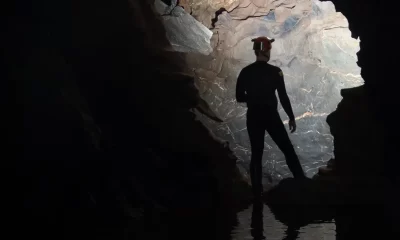

Located in Southeastern Mexico on the Caribbean coast, the Yucatan Peninsula is the home of cenote diving. The Cenotes are the natural sinkholes that serve as the entrances to the underwater cave systems. In local mythology, they are the entrances to Xibalba, the Mayan underworld where the gods and ancient spirits reside.

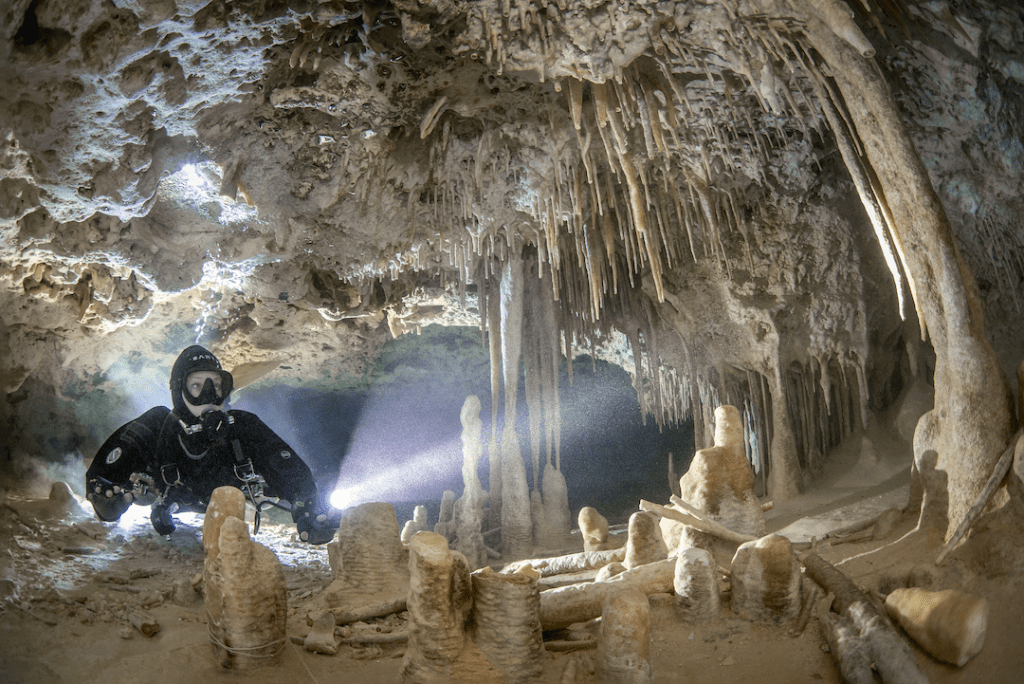

When you dive into the cenotes, you enter a world of crystal clear waters and dancing sunbeams. As you venture further into the caverns and caves, you swim amongst ancient stalagmites, stalactites, and intricate formations ranging in size from tiny soda straws to enormous columns, with room after room of changing vistas.

I discovered my passion for diving over 20 years ago when I emigrated from the UK to New Zealand. A decade later, the wanderlust struck again, but this time with renewed force, so I quit my full-time job to pursue diving in far-flung places. This journey eventually led to settling in Tulum where the magical cenotes truly brought my dual obsessions of scuba diving and photography together.

The images I take in the cenotes and caves can generally be categorized in two ways. Some are quite clearly underwater landscapes with—almost always—a single diver to act as a focal point and to give context and scale. Others are perhaps described best as environmental portraits that capture divers doing what they love in these stunning locations surrounded by mind-blowing sunbeams or passing through stunningly decorated sections of a cave.

Best known for my images of the cenotes and underwater caves of the Riviera Maya, I am lucky enough to now earn my living as a professional underwater photographer. I mainly shoot a mix of commercial work for dive businesses and scuba brands and photo sessions for visiting divers and freedivers. As well as making images, I have found a lot of enjoyment is teaching underwater photography, videography, and photogrammetry through both one-to-one coaching and group workshops. I am also lucky enough to usually make a few dive trips each year as a photographer for Dive Magazine (pre-COVID, at least).

Diving and photographing the cenotes is a sheer joy for me—the crystal clear waters and the incredible light rays always keep me coming back for more. There is something truly magical about the mix of light and the water. For me, wide-angle ambient light shots are perhaps the purest way to capture these scenes. My approach is very straightforward; it is simply about capturing the light, and very much a case of “what you see is what you get.”

“There is something truly magical about the mix of light and the water. For me, wide-angle ambient light shots are perhaps the purest way to capture these scenes.”

Whether I’m attempting to capture the breath-taking light beams at The Pit or the soft diffused light of Cenote Angelita, the approach is the same. I prefer to capture the moment, with minimal direction of the diver(s), and so I am generally the one working to find the best vantage point to arrange the relationship of elements in the scene.

Things start to get a lot different when we move beyond the daylight zone and start to capture images of the underwater caverns and caves. We find ourselves now constrained much more by our environment (although it has often been said that constraints can aid in the creative process).

Obviously, for starters, there is no ambient light at all and the only illumination is from the primary lights, video lights, and strobes that we bring with us on the dive.

When using strobes, you need to be able to visualize what the image will be before you take it, as they only fire to light up the scene when the shutter is pressed.

We no longer find ourselves in wide open spaces with the freedom to move in any direction but are instead constrained by the walls, floors, and ceilings of the caves we swim through and the guideline we follow.

These factors make cave diving photography much more of a team effort. I found out that communication underwater is always best kept to a minimum, which is where well planned teamwork and clear procedures make all the difference.

My favorite way to work is in a team of three: a photographer, a model, and a lighting diver (who also acts as the safety diver). My life is made easy in that regard as my partner Julia is extremely talented with both modelling and lighting.

We use a variety of lighting techniques with on camera strobes, off-camera strobes and video lights used in various combinations.

I do not tend to “stage” scenes very often; I find placing lights and lingering too long in any one area often leads to a loss of visibility due to percolation and silting. While I would dearly love to get a rebreather to help mitigate the percolation issue, it’s not quite on the cards just yet! Placing lights and posing models can also have a negative impact on cave conservation and so these need a very deft touch. Besides, I generally prefer a more run-and-gun style of photography that captures images of divers as they are diving.

One thing I particularly enjoy is the slow pace of cenote, cavern, and cave diving. There is no rush and everything unfolds slowly. Our dives are generally shallow, and we can take our time and enjoy some respite from the hustle and bustle of modern life.—TSG

You can find Tom St. George through his website and on Instagram