Education

Choose Your Students Well, Less Teacher’s Hell Will Slowly Go By

We’ve all heard the mantra, “Choose your instructor carefully!” Wise words, right? What about choosing your students? Here Stratis Kas, tech diving instructor and author of the book “Close Calls,” recounts his rather sharp learning curve in choosing suitable students! NOT! They did what?!?

By Stratis Kas

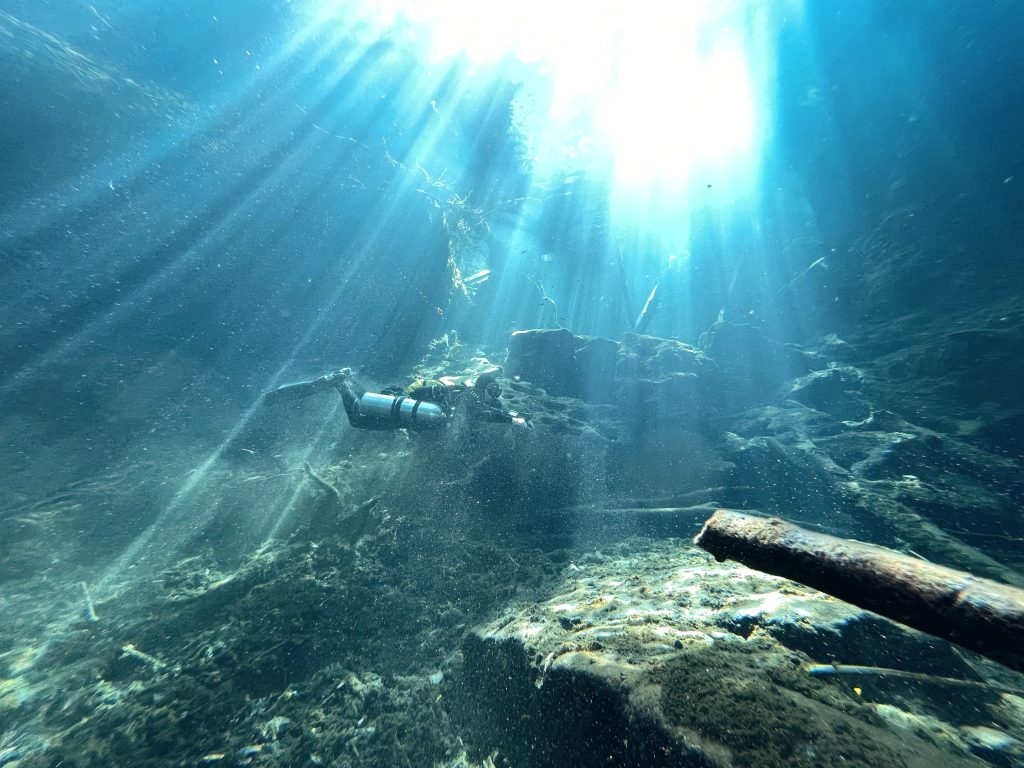

Header image and photos courtesy of Stratis Kas unless noted.

Choose your instructor carefully! This may be the most popular mantra in diving education. Heck, I have not only said it many times, I even wrote about it in the August 2020 issue of InDepth: Technical Diving Myths vs. Reality. As much as this remains true, it’s also incomplete. Diving education is not just knowledge. When done well, it’s mostly mentorship—…a proper relationship between student and instructor that starts during the course. As with most relationships, there are great highs as well as disappointing lows. Also, as in life, responsibility for the success or the failure is borne by both sides.

In an ideal world, all dive training should result in responsible and ever-evolving divers who themselves become mentors for the next generation. This, of course, is more than often not the case. As with all instructors, I have been both a student as well as an instructor many times. We all started as divers and then evolved throughout our training until finally some of us chose to keep on learning by electing to teach.

Unfortunately, in the ever-increasing commercialized reality that diving is becoming, it’s practically unheard of for an instructor to fail the student before the course has begun.

There are many influencing factors involved in the decision to not reject the unqualified student. One of those reasons is about business. A potential client who is turned away not only means an immediate, measurable loss of income, but even more importantly, can—and will—affect the instructor’s reputation in the market, as no rejected student will likely be honest about the reason the course did not happen. All the blame will fall on the instructor, who “for no reason” chose to not proceed with the training, even if, from the instructor’s perspective, that may have been the most responsible and principled thing to do. And if the student quits diving in reaction to the rejection, that rejection could have saved their life.

Some instructors might be personally challenged to succeed where others did not, or perhaps chose not to try. In these cases, the outcome, should it be positive, will be because the instructor expended a great deal of effort in order to allow the student to succeed and to achieve the best results. It may be driven by ego, but the end is met.

As training is still very unregulated, when it comes to skills and knowledge on all levels, instructors who encounter students who do not meet the minimum requirements to enroll in their courses are faced with a dilemma. What is the correct thing to do? Do instructors, as well as training agencies, need to become more exacting in their acceptance of a student? Do check dives need to become a standard?

I require all new students to do a check dive to demonstrate that all the basic skills and knowledge of their level are confirmed in order to focus on the new skills and not on what is supposedly already known. A classic example is when divers expect to learn position control during their cave course. This is unfair for both student and instructor, as the students do not utilize all the water time to progress in their specific course knowledge, and the instructor is now required to hybridize a very straightforward training plan, naturally with fewer chances of success.

I am lucky not to have to depend exclusively on diving training for my financial survival. But I also hope that even if that was my only source of income, I would follow the same protocols—making sure that my future students were ready for what they wanted to do next. Not just physically (very important) but also mentally. So what do I do when I am confronted with a very weak candidate?

Nowadays, I just say “No,” and I follow up with a very thorough explanation of why I said that. But, I haven’t always made this wise choice.

I hoped to enlighten, or at least entertain you, with a small selection of challenging situations that came my way earlier in my career. Some good, some bad and some, straight down ugly. Enjoy.

An unabashed cert card collector

We’ve all had them—the people posing as students saying they want to learn how to dive when what they really want is the card. The number of certification cards in their wallets matters much more than actually learning to dive, and what someone will do for a plastic card boggles the mind. Even so, rarely do they admit up front what they are after, but a few years back I received a phone call from a certification card collector who openly admitted that was all he cared about. Even though I tried to persuade him to look elsewhere for his training, he wanted me. In the weeks that followed, I started liking the guy, mostly because of his brutal honesty. So, I decided to give it a try. This was a non-tech diver who wanted to become Full Cave certified. As this is not completely uncommon, I was open to hearing more about it.

And then the madness began! “John” made it clear from the start. He did not care about theory or exams. On the other hand, I am a stickler for theory, and at the time I was teaching from my own cave diving manual for CMAS—a manual John never opened. When I explained that he would need to take the examin order for him to pass, he remained uninterested. Every dayJohn proved to me that he was not even close to being ready for the course. While I was used to students who tried to hide their weaknesses, John was open and proud about his.

I’ll admit it: I was hooked. When we arranged to go through his equipment needs for the check dive, he was expecting to use his brand new drysuit without proper training. I explained to him that this was not possible, and he then planned to dive the 11ºC/52ºF cave with his wetsuit. What this man was apparently willing to do for a plastic card amazed me.

Next, when we discussed the need to meet at a local swim pool to do the check dive, John informed me that he needed for the session to not exceed 45 minutes because he couldn’t go longer than that without a cigarette break.He also said he planned to urinate in the public pool whenever he needed to rather than exit the pool and use the restroom. I was working on how I could handle the untenable situation when a drowning accident resulted in the cessation of access to all public pools, saving me and tightening John’s timeframe. He then decided to train with a different instructor, much to my relief, and some time later I learned that he had gotten certified to teach cavern courses with his full cave certification card.

What should I have done differently? I should never let myself agree to ‘teach’ this arrogant man. I was fascinated with his obvious disregard for protocol, and somehow must have let myself believe I could do what no other instructor could–help him to see the importance of proper training. Never again.

Students with personality conflicts

As a brand new instructor, I was inclined to “over deliver,” and perhaps this influenced my decision to teach three divers at once. Knowing what I know today, I would advise a new instructor to take on one or two students, but certainly not three simultaneously. Only experience can help an instructor read signs that precede potentially dangerous situations, and it’s very difficult to keep an eye on three students simultaneously.

My three students—all men—were uncomfortable with one another from the outset. Tension was palpable in all our classroom theory sessions, complicated by conflict in the relationship dynamic of a recent breakup of two of the guys with the addition of a potentially new friendship forming. There was lots of competition, and the mood was surly.

A check dive was not required—my second mistake—since all of them were already tech divers, having been certified by a well-known instructor. One of the divers, “Bill,” was the better diver, the only one who seemed to be suitable for the course, and the only one able to remain still in the water and pass all the open water skills and the cavern dive. His success escalated the rivalry between the other two, as they tried to best one another to be as good as Bill.

During our first full cave dive, we had to pass through a restriction at the cave’s entrance. To my surprise, Bill refused to do so. We consequently exited the cave and Bill ungeared.

I then dove with the other two divers, and a few minutes into the cave, an emergency was simulated, and one of the started self-rescue procedures, ignoring the protocols of team diving. The dive was called, and at debriefing, I terminated the course.

At a later date, one of the two divers successfully finished his cave training with me, but Bill and his new friend chose not to learn basic skills that would allow them to be ready for a proper cave course. They were both later certified as full cave explorer level by a different instructor.

What should I have done differently? Certainly I should not have jumped into a three-student course on my first experience as a new instructor. Also, I needed to be more aware of team harmony—and disharmony—and to relay to my students exactly how important it was. If two divers are at odds with one another, instructors have every right to question their willingness to save one another in a cave.

Note: Nowadays, I use this restriction to check the ability of all new full cave divers to deal with the actual environment they are certified for. If that restriction is too much, full cave diving is too much.

The uptight, overstressed candidate

This is a case of a student’s overall demeanor, possibly practiced, belying his internal signals of distress.

“Joe” was an educated man in his early forties. He was successful in his work that involved not only following protocols, but also thinking outside the box. He was an ideal candidate, or so I thought. He was excited and focused and a pleasure to teach. Our open water sessions were successful, as he performed all simulated skills with ease. I noticed but ignored that as he was performing skills well, there was tension in his hands. Even as he was simply making a tie off, his hands shook. Because he was such a high performer, I didn’t examine it more closely.

Our first cavern dive was reachable only by boat. We were anchored in front of the sea cavern, with the seafloor 5-7 m/16-23 ft below us. The cavern was beautiful and perfectly suited for a first overhead experience. This cavern was nearly all open on top, with a massive central air space. To a student, it could feel like cave diving; I knew better.

Joe geared up and chose to jump in before he donned his fins, claiming that was simply easier for him. However, as soon as he entered the water, his overinflated wing’s valve popped, and he lost all his buoyancy. He was properly weighted, and had he been wearing fins, he would have had no trouble remaining at the surface, even with a failing wing. He also had two fully functioning regulators, one in his mouth, and he could see the bottom a few meters below him. His fins were in his hands, but none of that computed with him, and he panicked. He began to fight the descent, and he screamed. Three people immediately jumped in to save him, and once back on the surface, he needed 10-12 minutes to recover from his panic attack.

What should I have done differently? I needed to watch more closely for subtle signs of stress, because “Joe’s” slight signals that he was frightened and distressed, even though they belied his general demeanor, were real, and they were red flags that I missed.

The privileged professional

“We never stop learning”. If only that was true.

Some of my worst students have been diving professionals who want to be certified at technical and cave levels in order to teach these disciplines at a lower level.

Two separate instructors, “Adam” and “Ned,” were part of a course that also involved a student who was not a diving professional, “Roger,” and that combination proved disastrous. Once our dates were firmed up, I prepared the proposed schedule and sent it to each student. It was fully detailed, including breaks, transfer times, and meals. In respect of my training organization, the schedule fully followed the standards, even if it was intense. It was a full cave course. It was going to be intense.

In addition to the email, I organized a group video call for the purpose of allowing the students to introduce themselves to one another and begin team building.

It was a cold winter day when we all met for the first time in the classroom. I had the chance to informally discuss diving with the two professionals before the other diver arrived. Then, as soon as the class began, I felt that we were conducting a co-teaching course with Adam. Not only from his interference in my theory, but also his constant interjecting questions that were more commentary than actual questions, as well as in his body posture in relation to the other students.

I took Adam to the side and explained to him why this was not only okay for me and the other students but essentially also for him, since, by taking on that co-teaching role, he was not absorbing information the proper way. Adam did not like that, but he seemed to accept it, and we moved on.

Not more than one hour more passed, and on the theory break, Ned informed me that he, as “he already had the skills,” he would not be able to do the swimming pool skill sessions in the late afternoons. His reason was that he had to go back to his family and take care of the kids.

As readers probably know, advanced cave diving courses are not a 9-5 thing. They cannot be. Their success is based on full immersion of the entire unit (students/instructor/assistants) for the length of the course. Dive courses are meant to keep divers alive—and therefore to keep them with their families. Ned was shocked to hear that his request was not going to be approved, because he was sure he would have the understanding of a fellow instructor. Ned decided to stop the course, and he asked me for a refund, then a partial refund, and then finally threatened to report me to my training organization for not catering to his specific needs. As a reminder, the full schedule with exact times and explanations had been presented before the course started, making his threat baseless.

This is important for all instructors out there: do not make special exceptions that modify your course and what you need to make it fair, equitable, and effective, to satisfy the wants of your students. That does not mean that an instructor should not try to accommodate requests, as long as they are reasonable and do not compromise either the scope and integrity of the course or the other student’s needs.

The next few days went on quite okay. Adam and Roger (our nonprofessional student) got along very well, although Adam seemed distracted. After the fact, I concluded that he had continued to resent me and spent a lot of time in his mind imagining how he would be conducting the course.

On our second to last dive, in an objectively easy cave regarding navigation, Adam was connecting the open water to the cave’s main line. I was following side-by-side with Roger, checking Adam’s placements and tie-offs. At the main line connection, Adam connected his primary reel onto the main line and directed the reel’s double ender toward the inside of the cave. In cave diving training, we consider all bolt-snaps and double enders connected to the main line as directional markers. Therefore Adam made a critical mistake. A potentially deadly one. Even worse, Roger, who had grown not only to like but also to respect Adam as a diver, was looking at the reel pointing the wrong way, and wondering why it was not done the way he learned. Roger did not consider Adam a fellow student but a mentor, or even a co-instructor. Therefore, to Roger, Adam could not have made such a mistake, and Roger was unsure how to fix it in the field.

Roger looked at me and pointed at the reel. I wrote on my wet-notes, “what do you think?” Roger froze. A minute passed, and I called the dive. On our way out, the primary reel got cut, and Adam executed a perfect repair. Out of the water I asked them both if they knew why the dive was called. Roger stood silent and Adam, in a good mood because of the great line repair he had made, asked if any of us had a serious failure that justified the dive ending.

Back in the classroom, I asked Adam to repeat the same procedure of connection to the main line, which he did correctly this time. I requested another open water simulation skill day to refresh and make sure potentially life-ending mistakes would be avoided. Roger was still frozen, but Adam, when confronted with the mistake, denied that he made a mistake on the connection (thank God for my GoPro), then he tried to explain why “it was not such an important mistake” being so close to the exit, until he finally left the class in a fury. The next day, Adam did not come back.

Many theoretical elements or practical skills can—and will—be learned by making mistakes and getting better each course day, but there are two categories in which I will not tolerate even a single mistake during the last phase of training. These are navigation and gas management. The reason is simple. They are the main issues that will kill you in a cave. And also they are simple enough for anyone NOT to make a mistake once they are learned. If a student makes a mistake regarding navigation, they have endangered lives.

What should I have done differently? I think I should have figured out what both of the professionals’ true motives were for taking the course. According to skill alone, they were probably suitable for cave training, but I believe they were status seekers, both of whom with attitudes of superiority. In Adam’s case, he was unable to be called out on a mistake, which made his ego such that he was not a good candidate. Roger is now certified and enjoys cave diving recreationally.

The student who could not count to save his life—literally

This will show my age, but there is a critical issue that recurs in many if not most young people today when it comes to general education and knowledge. Maybe it’s dependency on electronics that has substituted for using one’s brain, or (sadly) perhaps today’s teaching does not demand, nor even encourage, basic skills such as simple math.

It was a very hot summer night when I met Jonas. Jonas immediately showed a great sense of humor and comfort with himself. as the days passed, we became friends. Heasked me if I could teach him some tech theory in the afternoons on his breaks, and I accepted. Jonas had attended a few tech courses as an intern but got “charmed” by my methodology and approach when we were comparing plans. He wanted to feel “in control” instead of following blindly what a program would tell him to do. I liked Jonas.

Everyone has their strengths and weaknesses, and I am good at math. Relatively complex math thinking is easy to me— it feels natural. In my first years of teaching math requiring courses (gas management and decompression) I often saw students having a hard time following my logic. Not expecting that we are all comfortable with my personal way to interpret and calculate the above subjects, I decided to focus on helping them realize that once the logical thinking is there, the calculations were easy. And even more importantly, mistakes stood out because of this same logical thinking (example: if a double cylinder “gives” 400 minutes of gas consumption at 30 meter’s depth, something is almost certainly wrong).

Jonas showed from the start that math was difficult for him. Not an issue, I thought, as many people are not. Surely the basics would be there. At the end of our second session Jonas had to calculate 80/4 (=20). Surely this should not be a problem. But Jonas froze, and after half a minute or so, went for his smartphone calculator app. I immediately stopped him. “Come on man, how much is eight divided by four,instead? Let’s start there.” Nothing.

I was teaching decompression and gas management to someone who could not calculate simple equations, which would have caused serious issues for him, but one stood out more than the others. Since Jonas avoided all math related experiences, when he was asked to calculate gas for an emergency cave return scenario (he was already cave certified), he simply could not. During the next few days, we were supposed to discuss “in water gas recalculation,” and I had a dilemma that I could not take lightly. Jonas would not be able to learn any of this the proper way. At least not at what I consider minimum standards to justify the risk of technical diving and reduce it to “acceptable”.

I had to explain to Jonas that I could not certify him after all.

What should I have done differently? At the time of the event, nothing. Nowadays, I take much more seriously the assessment of pre-existing conditions when it comes to teaching these courses. I not only do a water check dive, but I also explain the importance of this logical thinking and basic (at least) grasp of math for diving training.

The student who certified himself

I believe (and hope) that this situation is so rare that it has to be an individual incident. Since it was not a proper paid course, and I was simply “mentoring” the individual while working together in the same facility, makes it so much more serious.

“Gus” was a talented young man who had been an athlete all his life and was good at anything sports related. As a consequence, he was very good in the water. His skills were top notch, and all signs pointed to him having (as per his own wishes) a very successful career as a diver. Gus was not yet 20 years old when the issue occurred.

We met in a hybrid tech/rec facility where, at that time of the year, mostly recreational divers were clients. For Gus, it was a boring time. Instead of visiting caves and doing deep tech dives, he had to guide in shallow reef dives. Since he was spending a lot of time with me, Gus started to feel comfortable with me, and he asked me questions like if I thought he should be certified at levels higher than he was, based on his skills alone.

The truth was that he had those skills, but there was no time for the instructor to spend training him because it was the busy season for the dive center. This frustrated Gus every day. Seeing that, and feeling sorry for him, I proposed to the diving center that—if they were okay with it—I would train Gus on our free days. My main motivations were mixed between it being a good thing to do and my own boredom. Also, I believed Gus had what it took to ace the courses smoothly and easily.

What happened next is a cautionary tale. As I entered the system to register Gus for the courses he wanted (I was planning to surprise him) they were not available. This could happen only two ways. Either I was not certified to teach them (which was not so) or he was already certified at those levels, which made no sense, as he kept saying how much he deserved to be certified. Naively blaming the system’s error, I let the issue go for the day. But, then the next day, I received an email from my training organization that congratulated me for certifying Gus at the course A and B. My mind was not able to process the information. What was happening?

When I confronted him, Gus initially denied everything. As I pressed him more to “confess,” he finally did, explaining that he deserved the certifications and that he had used my name as an instructor in the system which he had access to, to certify himself.

To this day, this is my most shocking memory as an instructor.

What should I have done differently? Nothing, except learn from it. Take nothing for granted, and never underestimate the deviousness of a highly motivated and unprincipled person to get what they want. My experience with Gus was an eye-opener and made me look at the world a little differently.

The student who gives up (all the time)

Being humble is nice. And it allows room, by removing the ego for new information and knowledge. But there is a limit to everything. And constantly putting yourself down (looking for a compliment maybe?) will not make you a better diver. Nor will it make you more likable.

“Martin” was one of those divers who started diving late in life, and he wanted to do it well—perhaps even perfectly. Which was why we got along as soon as we met. I failed to identify Martin’s problem because he seemed one one hand optimistic, while on the other hand, he kept using phrases such as, “I will never be as good as you,” which I should have seen as red flags. I ignored them, as many students start out with that attitude, but lose those envious statements as soon as they start to feel good about themselves.

As usual, we went in the water with another two students to do our check dive prior to the course. Martin was unlucky in that the other two students were probably the best I ever had the privilege to teach. Which meant that the difference was obvious. I think that, as a minority, Martin was sensitive about being seen as incompetent/inadequate, while the other students represented the norm. Our check dive included a series of skills performed on a stage made with a guideline in order to verify the student’s ability to stay still and control their position in the water. Having control of where you are in the water is an essential and often overlooked skill that, in my opinion, is absolutely mandatory for all overhead and technical courses. As these courses add new skills, the divers should never enter into such courses hoping to learn or improve these basic skills.

The two other students performed their skill almost proficiently from the first try, and when it was Martin’s turn, he could not do much. He was not ready for the course in reality. His love of diving was greater than his skills. Which is okay, especially for a person with a good attitude such as his. All I needed was to cater the course more specifically to Martin and separate it from the other two, obviously much more advanced, divers. This happens. I was not worried.

As I approached him, Martin stared at me, frozen. No matter what I tried to explain to him, or adjust things for him, he simply started into nothingness and floated like a dead fish. Initially I hoped that he was trying to achieve a still position in the water. I soon realized that it was not the case.

When the dive was over, as I was trying to explain our situation and how I wanted to deal with it, Martin began speaking very disparagingly about himself and saying that he now accepted that he would never be what he hoped to be, and that all the people who told him in the past that he was not good enough were right. I tried to explain that, considering that none of these people were serious divers themselves, and also were not in Martin’s life anymore, he needed to come out of that dangerous self-pity loop that he was in.

Sadly, Martin kept quitting every chance he had. From simply freezing underwater, using cold as an excuse to end the dive, to even leaving the water on his own. It took more than a month of back and forth, and a lot of buddy bonding drinking nights, to manage to get Martin to trust me that I would not be another one who would tell him that he was not worth it as a diver.

What should I have done differently? Not sure, as still today I strongly feel that there was no better way (for Martin) to proceed through the course. Not sure I am up for another one like this, though. For an instructor, the satisfaction of the student is very important. It’s what keeps me going. My small consolation is that at least now he can dive properly.

And then, even if so rarely, there are the ones I want to add extra diving days to their course. The ones that I feel, “I should have filmed this course and used it as personal promotion.” When everything is so smooth that I forget all the bad ones and remember why I love teaching so much.

You know who you are, and I thank you personally, once more.

Dive Deeper:

InDepth: Technical Diving Myths vs. Reality Greek cave instructor and filmmaker Stratis Kas explores some of the unstated myths about tech diving and offers up some hard-won consensus reality.

InDepth: How to Choose Your Dive Training by Rich Walker

Be sure to check out Stratis’ book, Close Calls, which details the close calls and near misses of more than 60 prominent divers who nearly lost their lives. If they made mistakes, you will too!

Stratis Kas is a diving instructor & explorer, a film-maker, adventurer and storyteller. Stratis Kas deals with all of his subjects — extreme weather expeditions to days lost in wilderness — with unique sensitivity and fearless focus. He travels to remote, sometimes risky, and often freezing locations to create stunning films that change what we know about diving expeditions.

Since 2016, he has led the Top2bottom cave filming team that specialize in Adventure Filming. In 2017, he finished his first film “Amphitrite” that won a finalist place in the film festival, “Short to the Point” in 2018. Currently he is finishing his second feature film “Infinite Liquid” produced by Because I Can Ltd.