Education

Compliance Provides An Illusion Of Safety In Diving

Using the recently published ISO standards for rebreather training as one of his examples, human factors coach Gareth Lock takes to task the discredited legacy belief that safety is best created through the development of, and compliance to standards. NOT. As Lock explains, according to the latest science, safety is created by constantly adapting and fine-tuning systems based on available information to enable successful outcomes in uncertain situations. Here’s how to reduce our reliance on compliance and improve safety.

By Gareth Lock

“Safety is not just the absence of accidents and incidents, rather it is the presence of barriers and defences, and the capacity of the system to fail safely.” —Todd Conklin Ph.D.

Modern safety science has moved away from punitive behaviour control and the premise that safety is solely achieved through the development of—and compliance to—standards. Instead, over the decades, there has been a recognition that safety is created by constantly adapting and fine-tuning systems (using experiential information) to enable successful outcomes in uncertain situations.

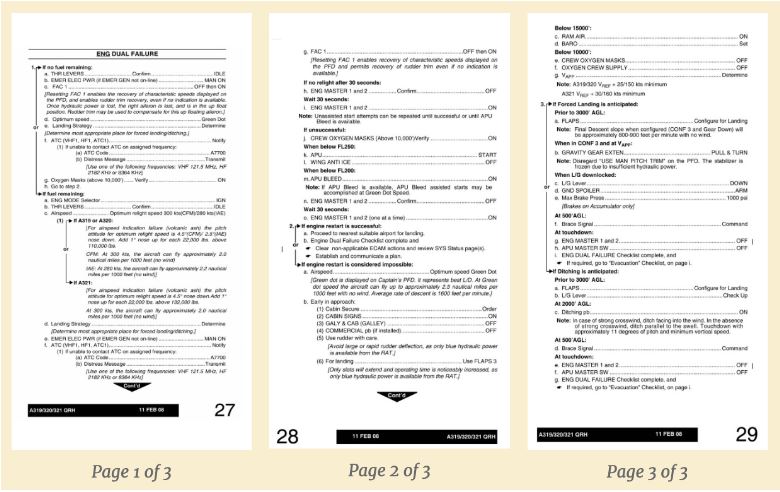

A classic example of this is Cactus 1549, ditched in the Hudson River on January 15, 2009. Shortly after take-off, the Airbus 320 hit a flock of geese, damaging both engines. The aircraft had to make an emergency landing on the Hudson River, as neither La Guardia nor Teterboro airports were believed to be reachable from the plane’s current altitude. Captain Sullenberger and his co-pilot Jeff Skiles modified emergency checklists to generate emergency power in a very unexpected situation. Sully summarised his ‘resilient practice’ in the following quote: “One way of looking at this might be that for 42 years, I’d been making small, regular deposits in this bank of experience, education, and training. And on January 15, the balance was sufficient so that I could make a very large withdrawal.”

Sullenberger and his co-pilot did not follow protocols because they understood the background behind the checklists, and this allowed them to modify their responses to achieve a successful landing. However, had they crashed into the tower blocks on the way to La Guardia or Teterboro airport, I am sure they would have been criticised for not following the checklists! The point is that ‘resilient practice’ comes from continued practice, adaptation, and reflection on those actions. It comes from a mindset that recognizes fallibility is likely and that rules exist to increase the likelihood of success—not to be blindly followed.

Those involved in the 2018 Thai cave rescue took the same approach. While there were rules to follow, they were not absolute; personal experience along with professional judgement meant that plans and situations had to be modified and adapted, leading to a successful rescue.

Adapting to the World Around Us

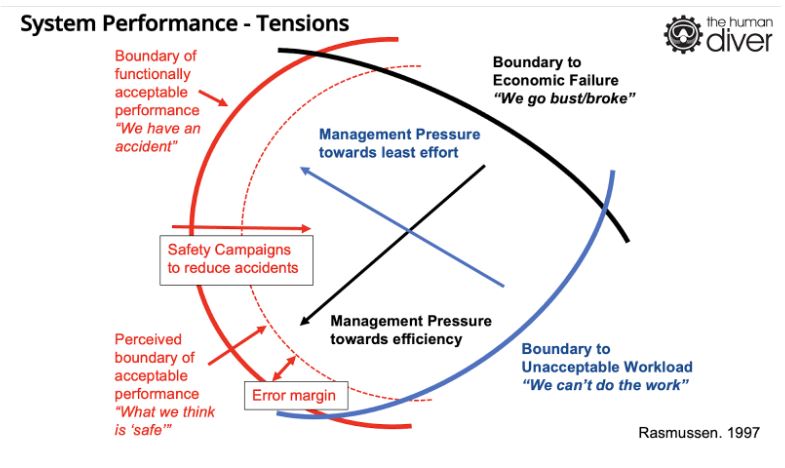

Adaptation is normal in a complex environment. We need to adapt to survive (physically and commercially) in a dynamic world where tensions exist. The following model from Jens Rasmussen shows the tensions that exist within a business, a diver training organisation, a dive centre, and even between instructors and divers. There are finite resources—people and money—that allow us to achieve our goals when used correctly (shown using blue and black lines, respectively). While the model shows ‘management’ pressures, these pressures also come from our own cognitive biases and the social environment. We want to save money and be more efficient with our time.

The financial and workload boundaries are quite clear—we know when we are going to run out of money, and we know how much time or manpower we have available. However, the red line (the boundary of unacceptable performance, or having an accident) exists in an unclear position in time and space. If we always knew where it was, we would operate right next to it because that is where we are the most cost-effective and workload-efficient—it’s also the riskiest place. And, because we don’t know the absolute position of the accident line, we bring the boundary back and call that a risk margin or margin for error.

At the same time as the resource and money pressures are pushing us left towards an accident, we also have ‘safety campaigns’ taking place which drive the operating position back from the red line into the middle. The downside is that it costs us more in terms of time, money, and people, so there is resistance to doing this. And up steps outcome bias: “If we don’t have a bad outcome, we must be safe!”

Herein lies the problem.

“If you complete all your paperwork 100% you will be safe,” said an insurance company leader at a DEMA presentation a number of years ago. I asked, “Do you mean safe from litigation, or operationally safe?” There was no answer. You might be safe from litigation if you remain 100% compliant with the rules (although some of the rules that dive centres and instructors have to comply with are not compatible; read on for some examples). But, you are not necessarily operationally safe, and you’re going to struggle to be commercially competitive if others in your commercial space aren’t following the rules.

The customers coming into dive centres for training are often blind to the standards that should be followed, and as such, their relationship with the instructor is totally based on trust—this is normal human behaviour. If the dive centre has an agency badge/logo above their front door, and all the dive centres in the area offer the same course, and they all appear to ‘comply’ with the RSTC/RTC standards, then the prospective client is going to choose the cheapest and quickest option (per Rasmussen’s model above).

Work as Imagined vs. Prescribed

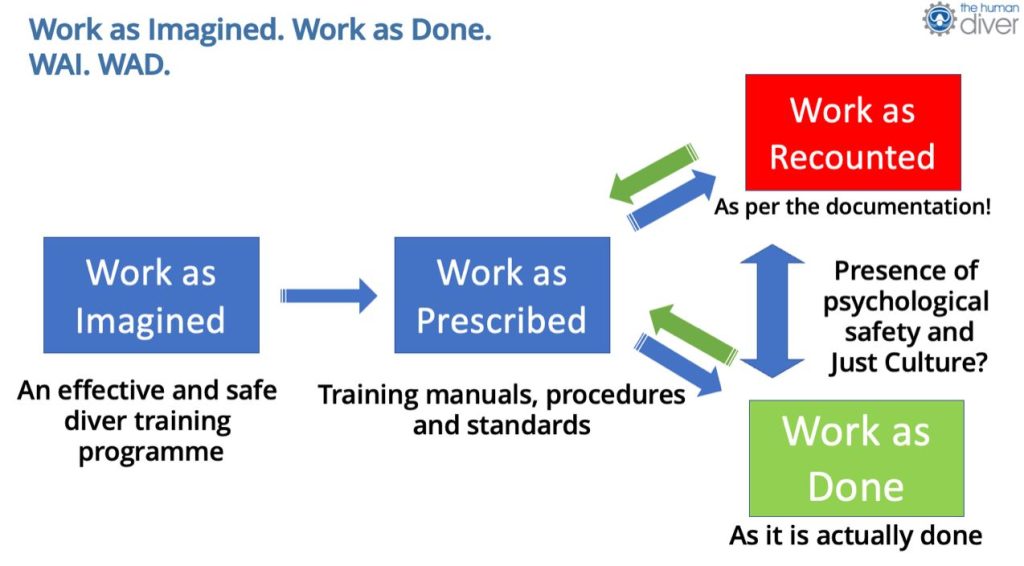

Gaps exist between what is imagined (the perception of a training program), what is prescribed (the standards from RSTC/ISO to agency, and agency to instructor in terms of training materials), and what is done (what actually happens on a dive course). This is what the following model shows.

We can identify the gaps between ‘Work as Done’ and ‘Work as Prescribed’ by having conversations with instructors and dive masters. Imagine that the dive centre owner or the training agency has a punitive approach to a breach of standards and non-compliance. If they ask how you teach your classes, the answer will be ‘Work as Prescribed’ i.e., to the standards. However, if that same centre or agency has a more open approach—one focused on improvement and learning, and with high levels of psychological safety and a Just Culture—the response to the same question will reflect ‘Work as Done’ which includes all the adaptations and workarounds that every operational environment has. Such an approach has to be role-modelled by those in the most senior positions in the organisation; otherwise, trust in the system will vanish.

The quality of a system is determined by the quality of the feedback within it. The more detailed and timely the feedback, the more likely improvements will happen quickly. Unfortunately, the majority of diver training ‘quality control feedback’ consists of tick boxes and ‘happy sheets’ which are filled in by a student who has no real idea of what ‘good’ looks like; and, because many performance standards are not made available to students, they can’t check. In addition, there is a fear that if they give the instructor a bad report, they might not be able to train with them in the future or be excluded from that community. This is a compliance-focused approach.

With the exception of a few agencies, after their initial assessment as an instructor, there is no practical assessment of instructors and instructor trainers in water and classroom delivery to ensure that their performance standards are where their agency says they should be. This is another tradeoff that can be mapped onto Rasmussen’s model above! “Instituting observation-based quality assessments costs time and money, and because we haven’t had an accident yet, we must be safe! We are compliant because we have ticked the boxes and all the paperwork is in place.”

Sussing The ISO Standards

Recently, two ISO standards for rebreather diver training have been published:

ISO 24804 “Recreational diving services — Requirements for rebreather diver training — No-decompression diving” and;

ISO 24805 “Recreational diving services — Requirements for rebreather diver training — Decompression diving to 45 m”)

In addition, three more ISO standards are in the final stages of review:

ISO 24806 “Recreational diving services — Requirements for rebreather diver training— Decompression diving to 60 m”,

ISO 24807 “Recreational diving services — Requirements for rebreather diver training— Decompression diving to 100 m”

ISO 24808 “Recreational diving services — Requirements for rebreather instructor training”

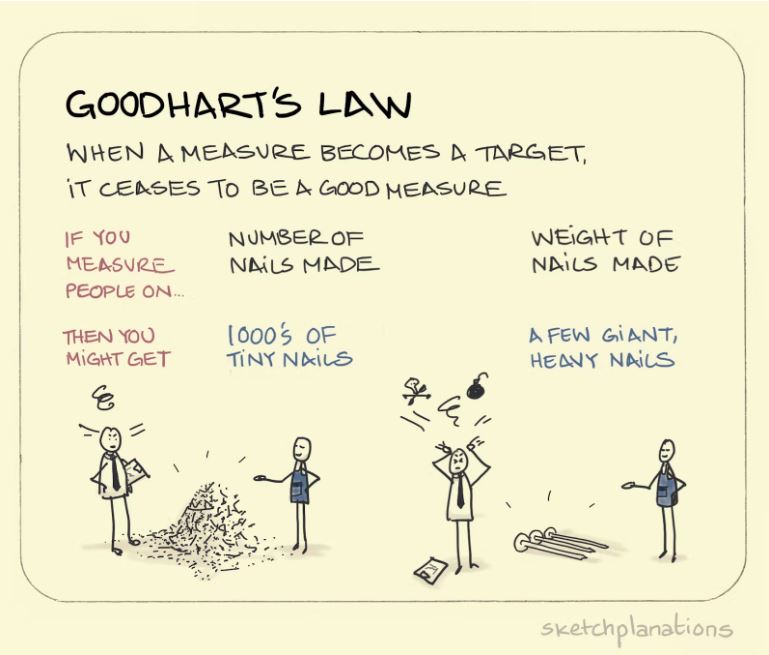

These standards are to ensure that agency courses are aligned with a common standard. This is a good start. The problem is that these standards are based on absolutely minimum standards to remain commercially viable, with the expectation that instructors will go above and beyond these to provide ‘quality’ training for their students—these statements were made at a recent diving conference. The problem with minimum standards is that they become a target. This is known as Goodhart’s Law—when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

ISO standards have a reputation in the safety world as being something that shows you have a process in place to undertake the activity, but it doesn’t mean that the activity is actually carried out across the organisation per the ISO standard. In the context of diving, the standards at the organisational level aren’t necessarily the issue—we should investigate issues at the dive centre and instructor level to ensure that the lower-level practices are aligned with the ISO standards.

Measuring the ‘quality’ of a training output by the number of hours or number of dives undertaken in a class or only to move from one instructor grade to another isn’t likely to be an informative metric in terms of ensuring safe performance and effective knowledge transfer because quantity-based standards alone can be gamed—5 x 20 mins dives to 6 m, tick!

A better metric might be to work out how much knowledge students retain X weeks or Y months after a class. This is especially important for instructor development; in the majority of situations, once an instructor is certified, which in some cases is literally a box-ticking exercise, then they are certified for good and only have to train a number of divers over a period of time and pay their fees. No one comes back to see if they are still able to teach as long as nothing has been raised in the ‘happy sheets.’

One problem with a standards-based approach is that a large proportion of diving accidents and incidents happen outside of the formal training environment. In this case, there are no formal standards to be compliant with. Drift is normal, and formal knowledge about how to execute a skill or apply theory will erode over time to be replaced by adaptations and ‘good practice.’ Sometimes that is good, and sometimes it is not so good.

This is especially important when it comes to critical activities relating to communication, decision making, and teamwork e.g., pre-dive configuration checks, gas analysis, gas switching, wreck penetration without a line, assumptions without validation, distractions, excessive task loading, and the normalisation of deviance.

Reducing Reliance on Compliance

There are a number of ways we can reduce reliance on compliance to produce safe diving operations:

- Have meaningful standards which are based on performance rather than box-ticking compliance—this requires more thought and investment in quality management.

- Increase the knowledge behind why the rules are in place. If you understand why rules are in place, when faced with uncertainty, you are more likely to be able to solve the problems from first principles.

- Teach instructors about the importance of psychological safety, how to create it, and the cognitive biases at play in a training environment.

- Develop effective debrief structures which allow post-dive debriefs to identify the gaps between WAI and WAD.

- Be proactive in finding out ‘what works’ and ‘what sucks,’ developing an understanding of local rationality—how is it making sense for someone to do what they are doing?

- Develop knowledge and practice of teamwork at all levels within the diving system so that when drift starts to happen, it is called out because of mutual accountability. That includes the ability to challenge senior instructors within an organisation.

- Examine the behaviours that are present within systems when certain behaviours e.g. compliance, are rewarded. Personal and organisational goals are likely to take precedence over compliance, so look at what can be done to make it easier to comply.

Aim For Sensible Compliance

Compliance provides an illusion of safety. Safety is created dynamically by those at ‘the sharp end’ through the constant refinement and adjustment of behaviours and the application of learned and modified skills, trading off between the time and resources available, and the amount of money available. The problem comes when you start creating punitive environments where compliance is more important than operational safety. The fear of noncompliance leads to situations where stakeholders miss the real risks. If we blindly follow the rules and don’t explore the boundaries of safety in a safe environment, situations outside of our training experience can escalate very quickly because we don’t know how to solve problems. And, when things go wrong, the response that “they should have followed the rules” completely overlooks the context that shaped the behaviours.

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 450 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture.