Community

Confessions of a Real-Life Entrepremer!

Professional mermaid Linden Wolbert, once dubbed “Mermaid to the Stars,” shares her personal journey from master diver into the watery world of mermaiding and exactly how she came by her tail. From edu-taining kids through mer-formances and her video series, “Mermaid Minute,” to her commercial film and photography work—did I mention Hollywood parties?—Mermaid Linden exemplifies the aquatic life well-finned. As a bonus, Vancouver’s Nerdmaid Faith offers a spe-shell mermaid resource guide. It’s enough to make you want to shake a tail (feather)!

by Linden Wolbert

Header image by Agustin Munoz

Predive Click: “Ocean Eyes,” Billie Eilish 🎶🎶

DISCLAIMER: The following passage is likely fraught with bad ocean puns. I can’t kelp it. Over the years, I’ve steadily amassed a rather over-whale-ming “Mernacular,” consisting of ridiculous, nonsensical and sometimes painfully cheesy “mermisms” and invented words. You’ve been warned, my fine-finned friend! If you dare, read on! Okay. Now where to start? Oh yes. Childhood.

When I was little, never in a million years could I have fathomed I’d become a mythical creature for a living. A half-fish, half woman, freediving globe-trotter? Nope. Dolphin-itely wouldn’t have guessed this career path. Growing up in Amish Country Pennsylvania, and like many kids in various regions of rural America in the early 80’s, we didn’t have cable television at my house for quite some time. PBS, therefore, was my go-to selection from the three channel options we had, outside of reading books and sitting in the yard watching bugs and birds with my binoculars and a magnifying glass.

Marty Stauffer and Jacques Yves Cousteau were two of my favorite “television teachers,” but my absolute favorite was (and still is) Sir David Attenborough. In my mind, he narrates my life! It’s far more interesting to watch an ant walk by, say, on the kitchen counter carrying a crumb, with Sir David’s unmistakable voice giving a thoughtful play-by-play on the whole scene, even if just in your imagination. You should try it. Super fun.

Not exactly a stone’s throw away from where I grew up, the Atlantic seemed pretty far out of reach. Embarking to see the ocean once or twice a year (if I was lucky) generally entailed something like the following: Very little sleep the night before in anticipation of a multiple-hour car ride with my parents and sister, followed by excitedly peering out the back window of the car for signs of the sea. Over the course of a few hours, the scenery would slowly morph. Cow pastures and corn fields gave way to highways and toll roads, then gradually to marshes, bridges and finally sand dunes. The best part was rolling down the car windows and smelling the sea for the first time on approach. Deep inhale….ahhhhh! The best! A colorful array of carnival rides would peek over the horizon, towering over the boardwalk like a toy model in the distance. Then there was the smell of the boardwalk: hot tar in the sun, french fries and deep-fried funnel cake punctuated with brine, salt and sunscreen. I get giddy just thinking about it!

In summer, my family would occasionally have a vacation in New Jersey or Maryland at the beach, which to me, was the stuff of dreams. Being anywhere near the ocean made me completely lose my little mind. I perceived the sea then (as I still do today) as a place of slow-motion beauty and mystery waiting to be revealed. A place where fantastical creatures frolic through the waves, tucking themselves away silently behind sea fans, rocks and corals to hide from predators and unexpected visitors. Tide pools were treasure box portals full of infinite possibilities—like little windows offering a teaser of what lay below in the fathoms. Sea anemones, small fish, mussels, clams, and the occasional horseshoe crab delighted me to no end.

Mermaid’s purses (skate and shark egg cases) were my favorite prize to collect from the shoreline. I would sit, entranced, watching the bubbles surface in the tidal zone after waves passed over the sand in retreat back to the sea. This was evidence of little critters digging their way to safety from cackling gulls and the plovers who’d run across the sand like adorable wind-up toys in formation. After body surfing until we were exhausted, my sister would cover me in a pile of damp sand, carving out the form of a mermaid tail around my legs as I lay beneath the cool weight of my new encasement. I’d sit there with a huge smile across my face, somehow comfortable in my temporary sandy cocoon of immobilization, until I had an itch on my nose. In my wildest dreams, I never imagined that my sand tail would one day be replaced by a beautifully crafted, prosthetic mer-sterpiece created by a Hollywood spe-shell effects artist, but I suppose stranger things have happened.

Taking The Plunge

So how did I go from the aforementioned sea squirt, to becoming a professional mermaid, you ask? Sure, I’d been to the Jersey shore in the summers. I loved to swim, a family trait. I loved taking photos, and capturing little things I’d see in nature. These passions evolved into the realization that I wanted to become a wildlife cinematographer and to share these things I loved so much, just as Cousteau and Attenborough had done for me. I also thought, “What better place to work than in nature and the outdoors?!” And so it was.

In 2000, I began my undergrad at Emerson College in Boston and majored in film and environmental science. I worked as an RA (mother hen in the dorm), repaired old 16mm film cameras called Bolexes in the basement of the school, and ran a jumbotron camera at the local concert stadiums to help pay for my tuition. I made my first underwater 16mm film on a Bolex I placed inside a fish aquarium, and filmed it at the local Chinatown YMCA swimming pool. I was beside myself with excitement when the film was processed and there was actually an image! In 2003, I left Boston for Los Angeles and enrolled in the Emerson College Los Angeles Internship Program. I haven’t left since.

I was hired as the Residence Director immediately upon graduation—which, unbeknownst to me, would be the last “real job” I would have to date. Before I left Emerson in 2004, I got my PADI Open Water certification and was practically inseparable from the water. I could hardly bear to be in an office once I experienced the kelp forests first hand and then traveled to Grand Cayman to help film a documentary about the sport of freediving. Again, my love of the water grew.

While in Cayman, I tried a monofin for the first time, thanks to Canadian World Champion Mandy-Rae Cruickshank, and the rest is history! At that moment, a huge light bulb went off. What if, instead of creating documentaries like everyone else, I taught kids about the ocean as a MERMAID? And just like that, I made my first big leap. I left my very comfortable position at Emerson to start my business. Suddenly, in my early 20’s, I found myself living in a room above the garage at my parents’ house. No promise of work and no idea how this would all pan out. It was liberating and horrifying all at once. As I would learn, when I take a leap, a net magically appears. The saying is true! Never, of course, in a way I could have predicted.

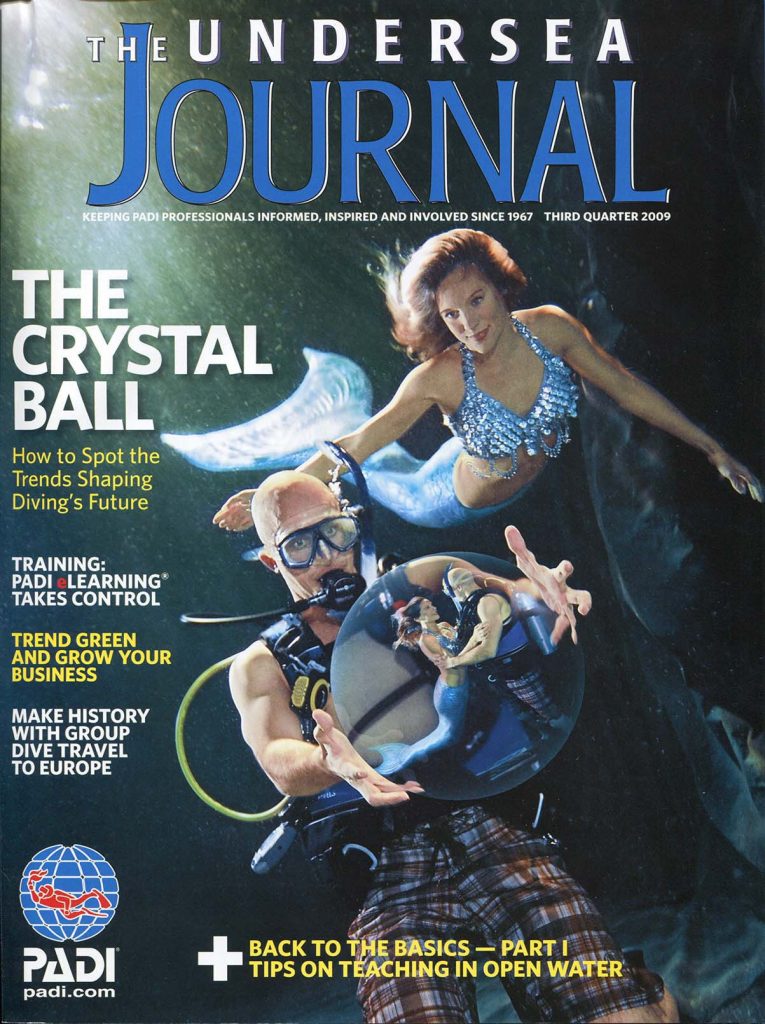

The PADI training agency hired me as an underwater SCUBA model, and I traveled the world and got paid to dive with them. A dream! Around that time, I traveled to Tokyo and became certified as an International AIDA Judge for the sport of freediving. I was obsessed with the sport, yet had no interest in competing, so this was perfect. I got to observe world class athletes setting unimaginable records, travel to exotic locations, and master my freediving techniques from the best possible coaches. Life news flash: Toto, I don’t think we’re in Amish country anymore.

Suddenly, I was a first-time business owner with an idea for which there was no existing business model. It was a huge learning curve. Here are some of the skill sets and areas I have had to do my best to learn and manage over the past decade to keep my mermaid business flourishing: Performer, Filmmaker, Special Effects Artist, Product Designer, Model, Quality Controller, Makeup Artist, Negotiator, Accountant, Seamstress, Educator, Musical Composer, Editor, Aquatic Athlete, Web Designer, Childhood Behavioral Expert, Set Designer, Social Media Expert, Storyteller, Wish Granter, Marine Biologist, Citizen Scientist, Writer, Conservationist, PR Specialist, Brand Ambassador, Producer, Underwater Stunt Double, Director, Professional Mermaid, andI’m certain I’m missing something, but….you get the picture. Needless to say, I have acquired quite the hat collection.

This job has taught me more than any office position ever could have and has provided infinite rewards! Is it horrifying at times, both creatively and financially? Absolutely! Do I have days where I question myself and wonder, “Am I completely mad for doing all this?” Bloody right I do! But then I realized what happened;somewhere along the line, I accidentally became an Entrepremermaid. Yes, it’s a thing—Entrepremermaiding. Okay, so I made it up. Now I cannot imagine living life any other way.

Quite a Tail to Tell

My very first tail, or as it is now called, “Tail 1.0,” weighed 35 pounds/16 kg by the time it was completed. Its replica, known as “tail 2.0” and my current work (sea) horse, weighs in at just shy of 50 pounds, but is neutrally buoyant (it neither sinks nor floats). Craziness, I know. The sea stars aligned when I decided I must make my first tail. Magically, a man by the name of Allan Holt was delivered into my sphere of existence thanks to our mutual friend Adam. Allan wanted to make an underwater music video, and Adam suggested he speak with me about the logistics. I had no idea until our first meeting over dinner, when Allan and I sat down to discuss his music video, that he was a Hollywood special effects artist. He also happens to be one of the kindest people I know. He immediately expressed interest in helping me with my crazy dream: to create a realistic, swimmable, one-of-a-kind mermaid tail. Within a few months, we began the process.

It all started with a fiberglass mold of my body from the waist down, to make a duplicate of my legs. On top of my new, “fake legs,” we then took over 30 pounds of sculpting clay and began hand-sculpting each individual scale. The design of the tail fluke was next, which I had decided would be in the shape of a crescent. Why? Well, I had thought long and hard about how I wanted my tail to look. When I thought of traditional mermaid tails, I envisioned a dolphin-shaped fluke, or something similar to that of a whale tail. Deciding on a crescent shape was two-fold for me. First of all, I wanted to be unique. The shape should be something that, even if you only saw the silhouette of it from underwater, you’d know, “that’s Mermaid Linden.”

Secondly, the fastest fish in the world have flukes that are similar to that shape….think: sharks, sailfish, swordfish, tuna, etc. I used a method which has since been coined as “biomimicry,” which means to be inspired by something in nature to make it function well for human use. Well, in this case, it was for mermaid use! And thank Poseidon, it worked.

Over seven months and several thousand “sand dollars” later, we co-created my first born—my baby—Tail 1.0! After hundreds (or perhaps thousands?) of hours of clay sculpting, fiberglass-laying, bondo-slathering labor and love, that tail lasted me for almost a decade and swam in oceans, rivers, lochs, and pools around the world. It is amazing where that tail got to swim, and luckily for me, I got to experience those things because of it. Not only was this tail beautiful, sleek, and fitted perfectly to my form, it was unique. It was FAST. When I took it in the water, divers and strong swimmers with fins even had trouble keeping up. I learned quickly that unless we were filming something to demonstrate speed, I needed to intentionally slooooooow doooooown in this piece of fancy diving equipment. I’d call the Tail 1.0 a complete success! Since then, we have created two other tails from that same fiberglass mold. Tail 2.0, which is my current go-to silicone tail. Tail 3.0, which is made of a lightweight foam latex material, is a replica of its silicone siblings, and is intended strictly for land use and terrestrial performances.

Before tail 1.0 was even complete, I had begun getting bookings and “merformance” inquiries through word of mouth, thanks to people being aware that I was constructing a tail for almost a year. Here in Los Angeles, people love to have something at their party or event that nobody else has ever had. In the early 2000’s, nobody had heard of live mermaid performers for parties who actually swam. Sure, there were Ariel impersonators in long, green sequin skirts, but folks could scarcely believe there was some woman in her 20’s—a freediver—who donned a 35-pound silicone prosthetic tail and either taught your kids about the ocean during their birthday pool party, or swam as the centerpiece of your exclusive evening soiree in Beverly Hills with your celebrity friends. One party led to 10 others, and my client list became rather star-studded, rather quickly.

One publication eventually deemed me, “The Mermaid to the Stars,” because so many of my clients were A-listers or on the silver screen, big-name directors or a big shot in the music or fashion industries. This was all rather unexpected to the girl from Amish Country. When I started this whole idea, the motivation for me was to teach children about our oceans, their inhabitants, and how important ocean conservation is. Little did I know I would additionally find myself in so many unexpected and unusual booking/ performance scenarios.

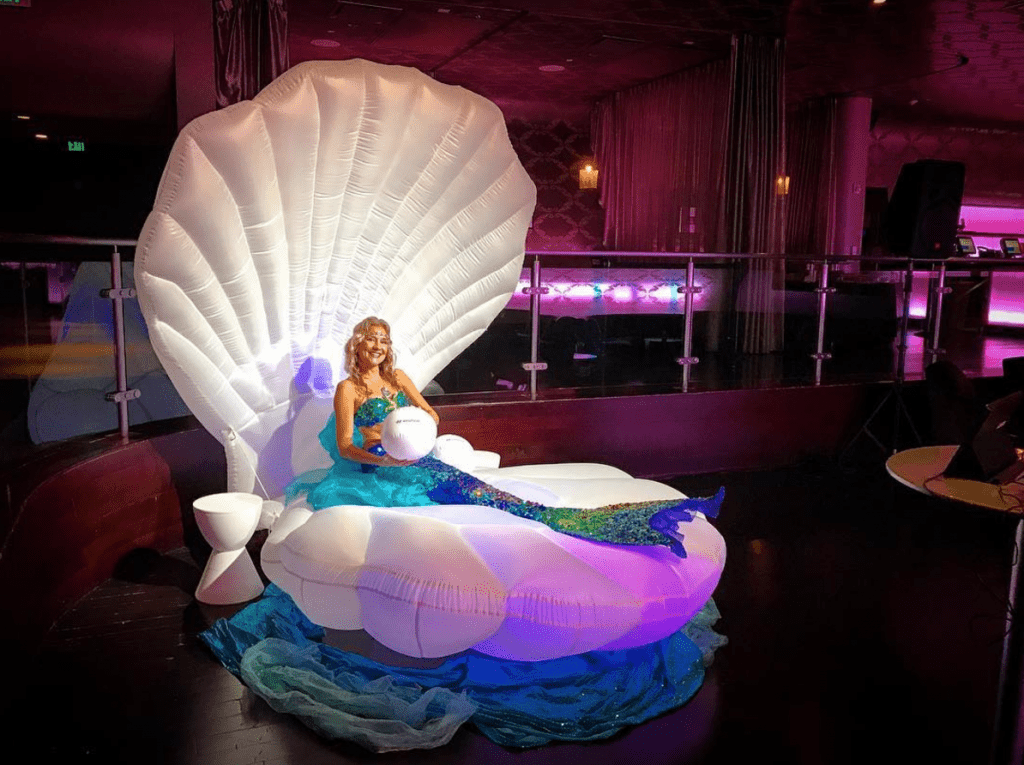

Some of my “merformances” have included: Underwater Ring Bearer at a SCUBA wedding in La Jolla Cove, weekly swim playdate mermaid for the who’s who’s children of Hollywood, underwater stunt woman for various commercials, films and music videos, cameo mermaid performer in feature films, mermaid trainer for “Dive Bar” up in Sacramento, CA, among others, official Mermaid “Edutainer” at the world’s largest fair, the LA County Fair, with my own stage, big screen, and shell throne . . . it goes on and on. Let it be known that while I am absolutely a people person, I love working with kids the most. And this brings me to, fins down, my favorite type of booking: Wishes.

When the Make-A-Wish Foundation first contacted me over a decade ago, I could barely get through all the nights and days until I’d get to meet the little girl who had made her mermaid wish known to the “Wish Fairies” who subsequently contacted me. This particular child wished to meet a mermaid, and then go to the Bahamas with her very own mermaid tail, so she could swim like a mermaid, too. After this first wish experience, I felt a sense of full-heartedness which was previously unmatched. I’m now convinced there is nothing quite like seeing a child’s face light up who has been through treatments and life-threatening circumstances for months, or sometimes years until that very moment. And, in that mer-ment, they forget all of that—the pain, the discomfort, the fluorescent-lighting of their hospital room, feeding tubes and blood tests—and they find themselves in a sort of suspended dream.

[popup_anything id=”10151″]

Photo by Bloomberg Businessweek

As a highly empathic person, being part of that experience in any small capacity is life-rendering. Dozens of wishes later, I never could have dreamed I would be performing a wish for my very own family. Reese, now 13, is my one and only niece. She has been battling leukemia since age 7, and at the time of my writing this, is about to undergo a bone marrow transplant. Knowing now from first-hand experience how hard it is on the kids themselves, as well as the families of ill children, to go through these types of circumstances, makes it even more important to help fulfill these wishes. I know how they feel. So while my true passion is creating Ocean Edutainment for kids, I can say with absolute certainty that participating in Wishes is the most fulfilling, perspective-giving facet of my work as a mermaid.

In A Mermaid Minute

Speaking of wishes, as luck would have it, while in the shower one day, I dreamed up what I thought was a brilliant idea for a children’s Ocean Educational series. It seems when I wash my hair and massage my brain (coral), it gives me great ideas in reciprocation—how kind of it! It was a simple premise: Each episode would be one minute about a topic in the oceans: an animal, phenomenon, or habitat. I would title this action-packed 60 seconds of ocean magic, Mermaid Minute!

With zero budget, equipped only with sheer determination and unabashed passion for sharing the beauty of our oceans with my “little sea fans,” I managed to scrape together my first season of Mermaid Minute and post it on YouTube thanks to the help of some wonderful friends and family. I borrowed some lighting equipment, tripod, microphone and an HD video camera (which at this point was still on painstakingly annoying Mini-DV tapes) and purchased a heap of green felt from the fabric store to create a makeshift green screen to post in front of in my tail so I appeared to be sitting on the “beach.”

Remember, I’d quit my one and only full-time job after college to pursue my mermaid career and moved into the room above the garage at my parents’ house as an adult child to start my mermaid business. It was the best thing I ever did! But yeah, not exactly the easiest thing as a grown adult. My neighbor helped me fine-tune my non-linear editing skills on Final Cut Pro, and I was off to the races. Over a decade later, Mermaid Minute has millions of views from all around the world, and season 2 overfunded on Kickstarter. Teachers began reaching out and using it in classrooms, and parents of homeschooling students employed it in their lessons. Friends with kids all told me how their children loved it, and to this day, it is the thing I am most proud of ever creating. All of my skills and passions are encompassed in it: Storytelling, cinematography, beautiful underwater footage, animals, science, natural history, music, sound effects, humor, and INSPIRING KIDS! What a joy it is when I complete editing an episode and post it up on YouTube!

About a decade ago, mainly because of Mermaid Minute’s success, I became involved with the Reef Check Foundation, an organization which has trained thousands of volunteer citizen scientists to count and track the changes of keystone species on coral and rocky reefs around the world. I had initially heard of Reef Check through a Howard and Michele Hall documentary I loved, “Coral Reef Adventure,” and was delighted when Reef Check contacted me. This eventually led to a position as a board member, and today I serve as the Co-Chair of the Board.

Through the years working with Reef Check, I have met some truly amazing people who are like-minded in the world of ocean conservation, diving, and exploring our seven seas. Russ Lesser, the long-time former president of Body Glove, was one of those people. Thanks to Russ, I began a partnership with Body Glove in 2013 which led to an amazing opportunity: designing my own signature line of mermaid-inspired swim products for kids and adults. Yet another feather in the cap—er—scale on the tail of my Entrepremermaiding journey, I learned all about manufacturing, product design, prototype testing, marketing, and even inventing.

I am so grateful and lucky that Russ saw such potential in me and my little brand. He said that the thing that really sold him on it all was my Mermaid Minute series. This meant the world to me! Since the inception of the Mermaid Linden by Body Glove line, our products have been sold in some of the world’s largest retailers, and our monofins are top-rated in their category of aquatics. I dreamed up the world’s first foldable monofin, which came to market last summer. Seeing kids, and now adults, around the world experiencing swimming with a monofin for the first time with my signature crescent fluke design makes me pinch myself.

“How exactly did this all happen?” I sometimes ask myself this question. One could say the sea stars aligned for me time and time again, but I know how many challenges I’ve faced. Anyone who has tried their hand at self-employment in a creative space knows it isn’t easy. Back in the early days of my mermaiding career, I was the only one in Los Angeles doing what I did. Over time, tail makers started popping up. Other men and women saw that this could be a viable career, side hustle or a fun hobby, and other performance companies and solo “mers” began appearing online in social media pages and forums by the hundreds. A noticeable upward tick in the trend of mermaids in pop culture became very apparent.

[popup_anything id=”10162″]

Photo by Courtney Pearson

Nobody is really sure where or why this happened, but within the span of a few years, mermaids were the new unicorns in the world of mythical trending. Mermaid mugs, greeting cards, t-shirts, and other mer-related chachki became commonplace in stores across the country, and soon the world. Instagram exploded with new profiles and accounts of “Mermaid (insert name),” and “Merman (insert another name),” with people showing off their newest monofins, shell tops, tails, and “mersonas” (mermaid or merman persona). Scores of others bought tails, created websites, and suddenly mermaids were popping up like mushrooms, vying for the same bookings and gigs in all corners of the world.

Before you knew it, Mermaid Conventions became a thing! The mermaid trend had arrived, and it still shows no sign of slowing down. Sales and projected trends for mermaid tails and accessories continue to rise. Even the SCUBA and Freediving world caught the wave at last, with several training agencies now offering Mermaid Specialty courses, where men and women can learn everything from proper movement in a tail, to breath hold techniques, to finding your “mersona.”

It has been astounding watching the “Mermaid Economy” blossom since it all began for me in the early 2000’s. I remember looking all over for any clue on how to design a mermaid tail back then online, and there was zilch. Now you can find all manner of tails, from lightweight fabric tails to heavy silicone custom tails like my own. Extra flukes and fins? You’ve got it! Companies like Mertailor, FinFolk Productions, Merbella Studios and countless others create extraordinarily beautiful tails in all forms, budgets, and colors. Some even light up! The future of mermaiding is bright, and it’s also neat that nowadays, when I tell people my job title, they don’t always look at me like I have an octopus tentacle growing out of my forehead anymore. “Oh yeeeeah! I have a friend who’s a mermaid, too!” is the common response now.

What a cool time to be a mermaid!

Dive Deeper

Mermaid Linden’s YouTube Channel

Mermaid Linden’s Mermaid Minute

The Diver Medic Webinar: Linden Wolbert – How Edutainment plants seeds of Hope

DeeperBlue.com Podcast

With a BA in Film and Science (underwater cinematography) from Emerson College in Boston, Linden shares the life aquatic with others via underwater wildlife videos and live mermaid performances. Mermaid Minute, her educational ocean web series for kids, “edutains” young viewers about an array of animals and sea life. Her passion is reaching as many children as possible with her message of conservation, education and exploration thereby transforming them into our world’s youngest ocean ambassadors. As a PADI Master Scuba Diver, underwater model and full-time professional mermaid through her company, Mermaids in Motion LLC, Linden would spend all of her time in the water if her hands didn’t get so pruny! A long time International AIDA Freediving Judge, she has traveled the globe to officiate world records that span far beneath the ocean’s surface. Linden serves as Co-Chair of the board of Reef Check Foundation, a co-host of the Webby Award-winning Deeperblue Podcast, and a Volunteer Mermaid for the Make-A-Wish Foundation.