Exploration

Confessions of an Aspiring Shipwreck Explorer—I’m Obsessed with the Lusitania

Entertainment entrepreneur Nikolaus Thomas Grohne has found a new avocation—helping to create awareness about the importance of shipwreck exploration and preservation. His obsession du jour, Gregg Bemis’ RMS Lusitania, which is currently being explored by Lusitania Project 17. Included is a selection of aquaCORPS Journal reports from the first tech dives on the Lucy, led by deceased British explorer Polly Tapson.

By Nikolaus Thomas Grohne

Header image and other photos courtesy of Lusitania Project 17

🎶 Predive click: “When the Lusitania went down” by Herbert Stuart (1915)

I’ll start with a confession: I’m not a certified scuba diver. I’m not a marine explorer or archeologist either. I actually work in entertainment. I simply believe that shipwrecks are precious time capsules containing important artifacts that bear witness to bygone times. These need to be recovered and preserved for posterity as part of our human history and heritage.

After noticing the lack of public awareness and funds available for this essential cause, I have been committed to finding new ways to support the exploration and conservation of vintage ocean liner wrecks. In short, I believe that we all can do our part, even from the comfort of our own homes.

I have been obsessed with vintage ocean liner wrecks from the Belle Époque era since the moment I watched a National Geographic VHS of Robert Ballard’s “Secrets of the Titanic” as a kid. From this point on, I literally read every book about her I could find, collected all kinds of Titanic related merchandise, and built plastic model kits. My sister would always say that no one else could possibly be as obsessed with Titanic as I was—little did we know how wrong her assumption would later turn out to be.

After high school, I would visit literally every Titanic exhibit within a 160 km/100 mile radius. Looking at the numerous artifacts recovered from her wreck 3,861 m/12,600 ft below the surface of the Atlantic was both extremely fascinating as well as deeply touching, especially when personal belongings of passengers were on display. The same year, James Cameron’s movie Titanic came out, and my desire to see her wreck with my own eyes, up close, intensified. Yet for someone like me growing up in the middle of Europe far away from the oceans, without the means or opportunity, such an exciting endeavor seemed to be completely out of reach for me.

Then, in June 2009, a spur-of-the-moment decision would unexpectedly propel me in the right direction. I watched an episode of the Discovery television show Treasure Quest documenting an expedition to the sunken British passenger liner RMS Lusitania, the second most famous shipwreck in the world after the Titanic. The documentary followed Gregg Bemis, the American entrepreneur, deep-sea explorer, and owner of her wreck, who was trying to answer the lingering mystery as to what caused a massive second explosion aboard the Lusitania after she was torpedoed by a German Imperial Navy U-boat 18 km/11 miles off Kinsale at the Southern coast of Ireland in May 1915.

I instantly became obsessed with the crazy idea of trying to get involved in one of his future expeditions, and I couldn’t help but google Mr. Bemis’s phone number and call him at his residence in Santa Fe, New Mexico. At that time, I knew I had little to offer to him apart from my enthusiasm for a future wreck expedition project; nevertheless, I pledged to try to support his cause going forward. Over the course of the next five years, I would follow up with Mr. Bemis every three to four months to get a better understanding of his mission and his project.

First date with the Lusitania

In January 2014, I started my first attempt at keeping my promise and met with Mr. Bemis in Dublin to discuss pitching his exciting wreck expedition project to the showrunners of a popular daily educational show, which my employer at the time—one of the leading television networks in Europe—was producing. Sadly, the showrunners did not recognize the historic significance of the Lusitania in the context of World War One, and the potential that Mr. Bemis’s historic endeavor would have, and passed on the project.

Yet, this setback did not deter me from developing other ideas and I did the best I could with the means available to me. In 2015, I created a website and a Facebook page (now renamed, Preserving the RMS Lusitania) with the intent to raise awareness and funds for his ambitious project. Even though the fundraising part wasn’t really successful due to its limited reach, my Facebook page would slowly but surely gather some attention from divers involved in previous dives to the Lusitania wreck, and I was very excited about that.

In the first quarter of 2019, Mr. Bemis told me that the Irish government had granted him a preliminary license for this intended extensive wreck expedition. I was working in television in Los Angeles at that time, so I developed pitch materials and used my connections in the industry to find a way to pitch the project to one of the major US television networks. In October 2019, the pitch was successfully made to a major network. But, despite being very interested, they decided not to proceed with the project due to budgetary constraints and the pending status of the expedition which Mr. Bemis was planning.

When Gregg Bemis passed away in May 2020, I was deeply saddened. I had always been inspired by his remarkable persona and steadfast commitment to what he believed was right, irrespective of obstacles ahead or potential consequences. At first, I had little hope that I would ever be able to make a difference with respect to shipwreck exploration and preservation efforts; but, I recalled how much I had always admired his unwavering determination and decided that I could not give up on following my passion.

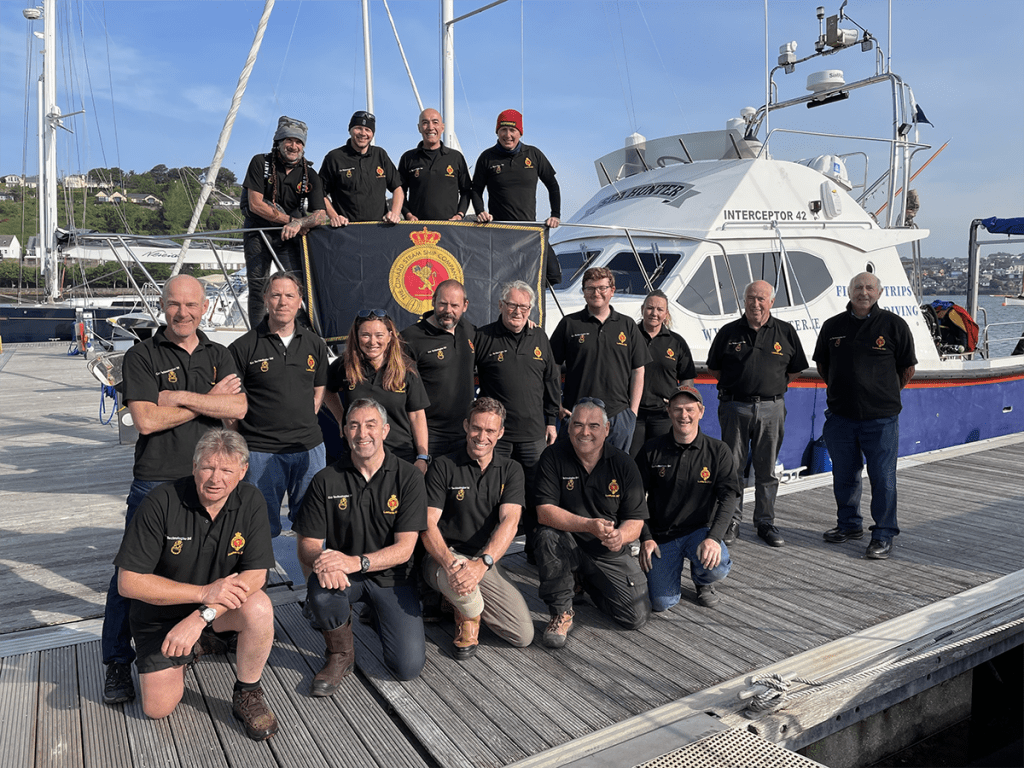

In July 2020, I talked with a couple of technical divers on social media who had been involved in a previous wreck exploration and documentation project named Lusitania Project 17, which was sanctioned by Mr. Bemis and the Irish government. This was an ongoing international project started by fellow divers Peter McCamley and Gerry Brown from Northern Ireland with the goal of surveying and digitally mapping the famous shipwreck using innovative photogrammetry technology. This technology creates fascinating 3D mosaics from sequences of still images or extracted video footage to get a more detailed and broader picture of the present state of shipwrecks which, in turn, is crucial information supporting the preservation efforts by divers, archeologists, and scientists.

The former 240 m/787 foot-long passenger liner lies at a depth of about 93 m/305 ft below the surface of the Celtic Sea, which is known for strong currents and poor visibility. In addition, there are commercial fishing nets that cover parts of the wreck. All of these elements hamper divers’ efforts. But, the adverse conditions at the bottom of the ocean are just part of the challenges that the divers have to face.

As with most other historic shipwrecks, the chronic lack of funds available for meaningful exploration and preservation efforts—divers typically have to invest their own limited personal time and money to do this crucial work— understandably slows the survey process down. As a consequence, only a limited region of the Lusitania wreck has been thoroughly surveyed with photogrammetry to date. But the lack of funding isn’t the only issue; there’s also a race against time as the condition of the wreck continues to deteriorate. Recovering as many historically important artifacts as possible should be a priority, and understandably so.

Middle Row: Dominic Robinson, Colin Brennan, Fran Hockey, Stuart Williamson, Padraig Begley, Christian Dalton, Claire Fitzsimmons, John Griffin, Jon Hayes. Front Row: Peter McCamley (team leader), Scott Yeardley, Will Schwarz, Frank McDermott, Alex Whitaker. Not shown: Gerry Brown and Vic Verlinden

The discovery of the wreck of the RMS Titanic in 1985, as well as the success of James Cameron’s blockbuster movie from 1997, has resulted in an unparalleled revival of interest in and popularity of vintage ocean liners likely not seen since the Golden Age of Travel. More than 23 years after the movie release, Titanic enthusiasts spend millions of dollars on books, merchandise, artifacts and reproductions, or tickets to permanent or traveling Titanic Exhibits around the world showcasing authentic artifacts. This, in turn, seems to allow RMS Titanic Inc, the company owning the salvage rights to her wreck, to fund proper exploration and preservation efforts. In contrast, many other legendary ocean liners like the RMS Lusitania or the HMHS Britannic seem to be left to their fates, exposed to the forces of nature, and are bound to ultimately disintegrate into unrecognizable piles of debris, just because of the lack of funds available? We can’t allow this to happen.

We all know that the majority of people who see a four funneled passenger liner assume, by default, that it must be the RMS Titanic just because they don’t know about the other thirteen four stackers, or ocean liners from the Belle Époque in general. Therefore, I believe the chronic lack of funding available for wreck exploration and preservation efforts positively correlates to the lack of awareness on the side of the general public. Yet, many initiatives to raise funds run by museums, non-profits, or other entities tender to special interest groups only and therefore have limited reach.

We can’t expect them to stem the tide alone and, needless to say, their efforts deserve our support. However, I think the traditional approach of educating people and raising awareness will not suffice to make a meaningful difference. In this day and age, the excessive supply of entertainment and information available is overwhelming and as a consequence people’s attention spans are short, so in order to get their attention, we need to make history more perceptible for them and emotionally engage them. For example, I know from my experience that being able to see historic artifacts and passengers’ personal effects recovered from shipwrecks up close is a very moving experience. Therefore, more efforts should be made to make museums and exhibits virtually accessible online.

Furthermore, historic shipwrecks tend to have an air of mystery and adventure surrounding them which capture the public’s imagination. I believe that higher levels of awareness and engagement could be reached by sharing the unique experience of wreck divers and wreck exploration with a larger group of people who usually don’t have the opportunity or the means to experience it firsthand themselves.

I strongly believe that it is our duty to properly preserve our history and heritage for posterity, but this is a massive task that can’t be accomplished without the public’s involvement and engagement. Going forward, I am determined to keep Gregg Bemis’ legacy alive, and I am committed to helping support scientific shipwreck exploration and conservation efforts. Utilizing my professional background in business and entertainment and the power of social media, I will be developing and implementing various marketing concepts in close collaboration with historic vessel owners, maritime museums, and archeologists from around the world. Together, we can make a meaningful difference.

Dive Deeper:

The Lusitania Museum and Signal Tower

Announcement: Our Lusitania Virtual Museum Experience

Stanford Magazine: He’s weathered many storms to secure ownership of the Lusitania wreckage. Now Gregg Bemis wants to get to the bottom of suspect events a century ago. What Really Happened? by Joshua Alvarez

The Lusitania Resource: Remembering Gregg Bemis

Nikolaus Thomas Grohne is an entertainment entrepreneur based in Los Angeles, California. He has been obsessed with vintage ocean liners from the Belle Époque era since the discovery of the wreck of the RMS Titanic in 1985. Nikolaus started his career as production assistant on television commercials and NFL Europe sports games in Frankfurt, Germany. While earning his graduate degree in international business at Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences and London Guildhall University, he also interned with several film production companies located in Los Angeles, New York, and Paris, France. After having worked as finance manager for several television production companies both in Munich, Germany, and Los Angeles, California, Nikolaus has found his new calling and is currently working on several concepts to help support scientific shipwreck exploration and preservation.

To connect with Nik, you can follow his page Preserving the RMS LUSITANIA on Facebook, or his LinkedIn profile