Cave

The Taming of the Slough: Crypt Edition

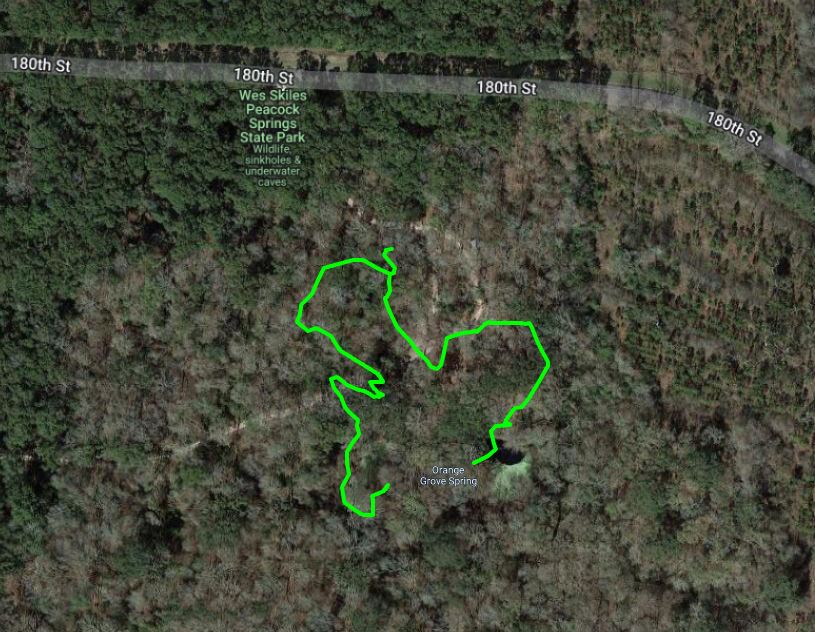

Rumors of a deep connection between the Crypt, a collapsed tunnel in Peacock Springs discovered by Sheck Exley in 1975, and lower Orange Groove, both located in Wes Skiles Peacock Springs State Park, Florida, only served to entice explorer Steve Lambert, who was determined to find the truth, after his team’s success extending Peacock III. Here is his story featuring a well-known cast of underground characters including Woody Jasper, Frank McNamara, Andrew Johnson, Thai Paul and greybeard Paul Heinerth who were involved in the find. Scoop that booty!

Text and images by Steve Lambert.

My name is Steve, and for the past four years I have had a somewhat unhealthy obsession with Peacock Springs. I couldn’t believe it when I heard that there was an alleged connection between the Crypt and Lower Orange Grove through a “deep section.” That rumor included the tale of a near-death experience—dive buddies frantically trying to get someone in the cavern to help, even though they had three hours of decompression to complete the dive. There were even furious police officers involved in the tale. Naturally, I had to go investigate. Over about half of a year in 2022, I was able to track down all of the pieces of this outlandish puzzle and put the story together as well as see the connection for myself. Nearly six months after that, I was able to begin an article on the subject of my desires.

History

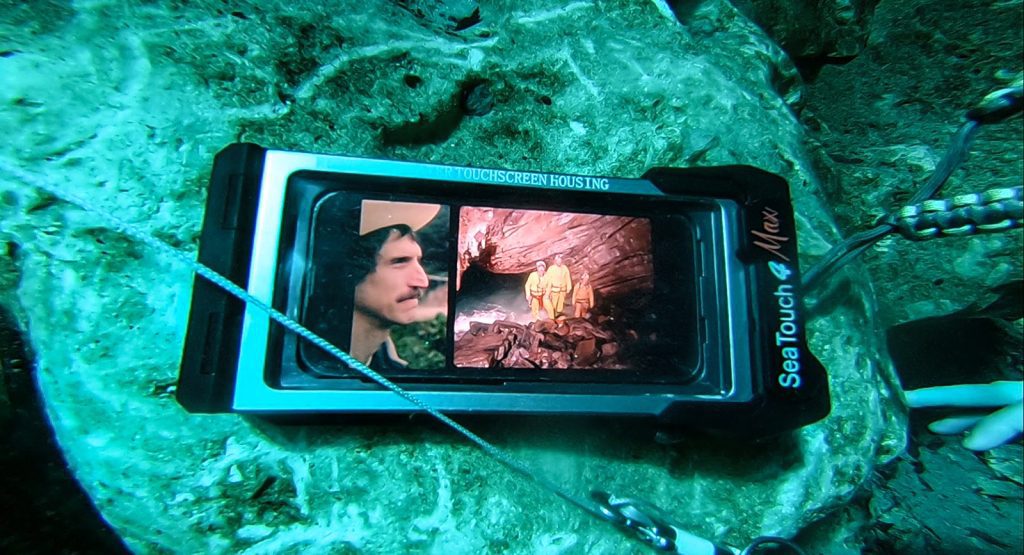

The deep section of the Crypt was originally explored in the mid-80s by Woody Jasper. In a time before most people had access to trimix or trimix dive planning tools, divers had to be resourceful to reach the far recesses of caves. When I asked Woody about diving the Crypt in the early days he told me “ I used a travel mix of half oxygen and half air [60% O2] so I didn’t start my bottom timer until I went on air in the upper Crypt, then I would stop my bottom deco time when I went back on the hot mix. Saved a shit load of needless deco. Max depth on the hot mix was 52 feet, so pushing O2 a bit on the return trip, but Nitrox hadn’t been invented then so we still thought two atmospheres (PO2=2.0) was safe.”

Using this method, Woody was able to shave off large amounts of decompression time from his dives. Keep in mind that this was at a time when “nitrox” hadn’t been invented and divers thought a PO2 of two atmospheres was within “safe” limits. It was also a time when you could count the number of sidemount divers on one hand, and only on a few fingers for the number of sidemount divers making deep dives.

Missed Connections

Frank McNamara started looking at Lower Orange Grove after Ted McCoy told him that he thought it connected to Lower Hendley’s in P3 (ironically, it was that same connection I was looking for when I began pushing P3 . Ted told Frank about some no-mount exploration he had worked on down in the “Little Sister” jump in the past, and he wanted to have a look.

Frank tied into the jump and headed off into a low flow, silty area. After accidentally making a wrong turn at a T, he ended up at a rock-on-clay restriction which appeared to be a dead end. “I went through it, he said, “and placed a silt stake and, after a turn, it popped out in a large room at about 46m/150 ft of water. This room had several breakdowns on the floor off to the left. After about 90m/300 ft, it got much bigger and dropped down to about 56m/185 ft deep and turned into a very wide and low tunnel covered in goethite with a decent amount of clear water flow.”

Frank continues: “I continued down this tunnel for a bit and came upon a breakdown with two different possible paths up (both nasty restrictions). I took the one that looked slightly bigger and went bottle off to get through. It popped into a big room going up a hill and after ascending a little bit, I found what appeared to be a very old line. I tied in and left my reel (my favorite one at that), assuming I’d be back to survey (vis was completely cooked from passing the restriction). I then turned to head out. At this point, I tried to go through the restriction without taking a bottle off and got properly stuck (it required exhaling fully to get enough slack to release my bottle).”

After the dive, Frank realized he hadn’t laid enough line to connect to Lower Hendley’s and assumed he had connected back into another line in Lower Orange Grove. About six months later, he went back to repossess his reel, but on this dive he went in on the line he thought he had tied into on his last dive. To his surprise, his line was nowhere to be seen. He left defeated, and it was over a year before he went back to recover his reel. He retraced his old line but, once again, bad visibility from passing through restrictions prevented him from getting the survey data and he still had no idea where his line had tied into.

“Years later, I heard about Andrew’s near miss down there, so Luke and I went back to follow the line that I had tied into back up. When we saw the little skeleton in the Crypt we knew I had actually connected Lower Orange Grove to the Crypt in 2016,” McNamara said.

Thai Paul

In 2020, Piyajit Pratipasen or “Thai Paul”—as he is known by many cave divers—was staying in Luraville for a few weeks and took up an interest in the Crypt. At this time, nobody knew that Frank had connected the two sides of the cave, not even Frank. Generally, when people say something “doesn’t go”, most people take it as gospel and never bother trying. Particularly if it requires a bunch of extra work and expensive gas to go see, and even more so if you have to swim any notable distance. These challenges didn’t bother Paul, and he spent the summer of 2020 making many dives down into the Crypt.

I joined Paul on one of his first dives into the area. Having heard many stories of collapse and instability in that area, I was intrigued and a bit nervous. Diving our CHO2ptimas, we swam in from PI along the Nicholson Tunnel and into the room at 70 feet. I followed Paul, who had been down through the breakdown before, into a small spiraling maze of breakdown. Eventually, around 120 feet deep, we hit a rock-on-rock restriction that I didn’t quite fit through. Paul popped off his CHO2ptima like it was nothing and slipped through the crack, but it had been several months since I had been on a rebreather due to my construction hobby, and I decided that low vis, depth, and a rebreather-off restriction took me to my limits for that dive.

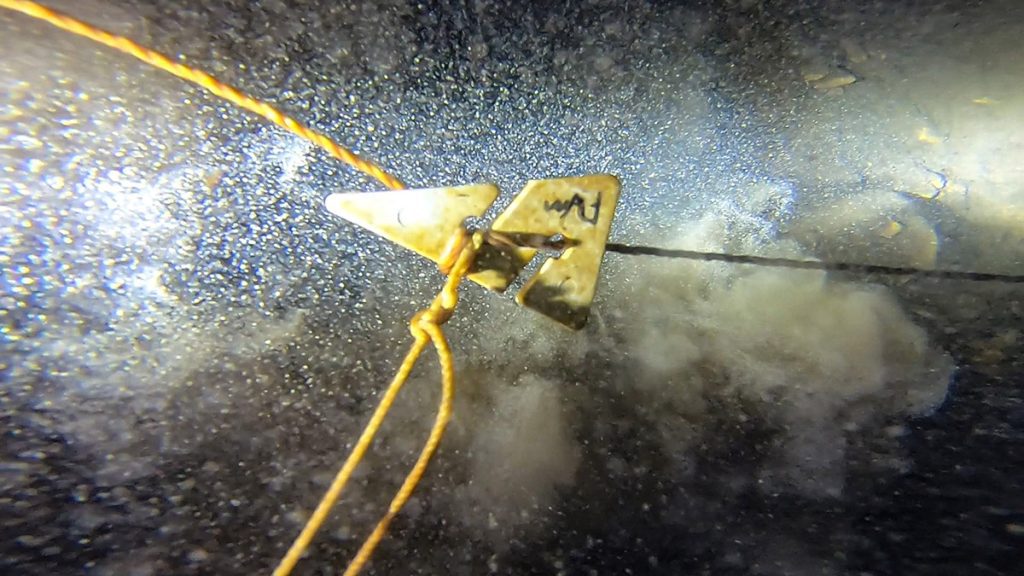

Over the next few weeks, Paul continued diving the Crypt with anybody he could hoodwink into going with him. Seeing as how there was no available data for the area, Paul decided to turn it into a survey project. As he mapped, he noticed it trending toward Lower Orange Grove. Eventually, his survey data showed the two locations trending towards each other, with minimal distance between them. He continued working on his survey for several weeks, until a dive incident stopped him in his tracks.

“The Dive”

Rumors about this dive were the hot topic of cave country for months. Sensationalized versions included broken equipment, breathing bailout down to the last PSI and tears of relief and near death were shared among divers, who were very surprised to hear that the Crypt went anywhere other than into a dead-end breakdown pile. When I finally got the chance to talk to Andrew over dinner at High Springs premier Mexican restaurant, I learned that the story was neither as dramatic nor as ridiculous as it had been propagated to be. I was both relieved and slightly disappointed that the chaotic ending to the dive had much more rational and controlled roots.

On Paul’s last dive into the Crypt, he went with Andrew Johnston. Paul was on a CHO2ptima and Andrew on a KISS Sidewinder. They snaked down the vertical breakdown through restriction after restriction and ended up in a gorgeous room deep in the Crypt. Paul was giving Andrew a tour and showing him all of the different lines in the area. He pointed him to the path suspected of connecting the two areas (which happens to be a restriction and the smallest, deepest place in the whole cave) and motioned for Andrew to have a look. Andrew wiggled into the small rock-on-rock restriction, visibility became worse and worse. After some struggle, he popped through into the bedding plane beyond.

Paul had taken Andrew into that section of Lower Orange Grove on a previous dive, and Andrew recognized where he was. Now in very low visibility, through a bottle-off restriction, Andrew was in a tight spot. All puns aside, he was quickly racking up deco sitting at 56m/184 ft, unable to communicate with Paul through the silt-out. He had to quickly decide whether to take the risk of trying to feel his way back through a restriction that he wasn’t comfortable with, or going to a known exit while leaving his buddy behind.

Paul was in the Crypt frantically waiting for the silt to clear. Worried that Andrew had gotten stuck, or confused by arrows from two different lines contradicting the exit, he waited at depth as long as he could before deciding he needed to get help. Paul swam briskly back to the entrance they had come from at PI, but had over three hours of decompression to do before he could safely ascend and ask for help. He was able to give a wet note explaining the situation to another diver in the cavern and had them take it to the surface while he finished the most stressful decompression of his life; he didn’t know whether his buddy was dead or alive.

Paul Heinerth was at Peacock Springs teaching that day and heard news of the situation. The IUCRR was alerted and a search began. Divers went to the Crypt to search, but Paul was still underwater and nobody else really knew their way around the Crypt. A local family swimming at Orange Grove spotted a diver in the water and alerted Kate Swanson. She jumped in where she met Andrew decompressing. Everyone involved was extremely relieved to hear that he was okay and he was able to exit the water without any major issues. By this point in the day, cave divers were all talking about the incident, shocked to find that the Crypt was connected to Lower Orange Grove, and even more shocked to hear the story of its accidental confirmation.

Getting the Data

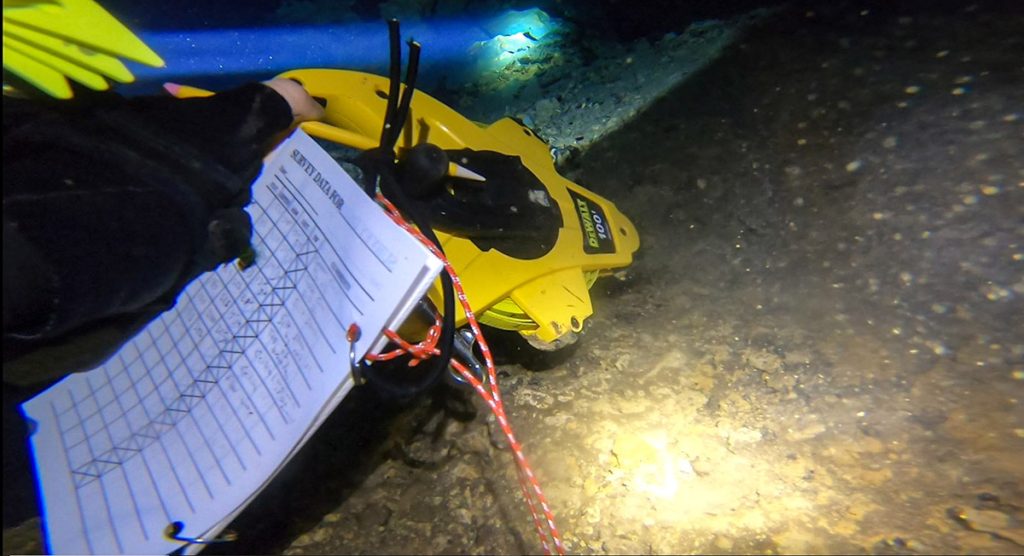

In the summer of 2022, I was having trouble recruiting people who hated themselves enough to suffer through long P3 dives, so it was time to work on the next project on my list until P3 was back on the menu. By then I had heard so many unreal versions of the story about the Crypt connection, I decided to go see the real thing for myself. I recruited my coworker and fellow CHO2ptima diver Justin Judd to go check it out with me. I figured if we were going to put the time into diving it, we might as well come out with something useful, so we decided to make it a project to get the data confirming the connection, as Thai Paul had misplaced his and there were no copies. Aside from that, we were testing prototypes for the Nomad Ray and this project would be the perfect proving ground.

Thanks to sponsorship from Dive Rite, Justin and I were able to spend six dives and nearly thirty hours on our CHO2ptimas completing a tape survey from the dock at Orange Grove to the surface at Cisteen. We worked our way in from both ends, slowly working through to the connection point in the middle. Surveying from surface to surface gave us the advantage of being able to determine our own loop closure without needing to rely on the accuracy of any previous survey of the system.

Having said that, it was Michael Poucher—the leader of the original Peacock Springs survey himself—who helped us plot our data, so I can hardly imagine he would have any trouble tying our data into the existing survey.I had expected the two areas to connect as described by Paul and Andrew, but what I had not expected was how incredibly beautiful the deep section of the Crypt was. The clean white limestone ceiling polka-dotted with goethite formations in one of the bigger rooms was absolutely stunning. We were intrigued to find a deep water source at the far end of the Crypt, and water flows out of this Northern source up into the PI side, and siphons off into Lower Orange Grove.

It was also very cool to see twisted, knotted line in the deeper section (with Woody Jasper’s signature three-knot ending) still in perfect shape after nearly fifty years. Another unexpected bonus of slowing down and looking at the cave in detail as we surveyed was finding more passage; we were able to lay around 152m/500 ft of line and found a more stable route to get to the deep section.

Making the Traverse, On Purpose!

After completing our survey work and having seen both sides of the connection and studying the “crux” of the traverse several times in great detail, Justin and I were ready to make the first dive by intentionally entering Lower Orange Grove and leaving from a different exit. We decided to enter from Lower Orange Grove, so we would be swimming into the flow as we progressed, making the deep silty restrictions easier to pass. With our intended route from Lower to Upper Orange Grove, no matter where we had to bail out, we would end up in the same place. We left two 80s of oxygen and a 50% bottle in the Orange Grove basin as we descended, carrying cave-filled sidemount LP85s of 18/45 as our bailout. On our last survey dive, we had staged two bottles of 50% at 70 feet in the Crypt in case we needed to bail out in the shallow section after passing through the restrictions.

This made the traverse a much more pleasant dive than we had expected. All of our other dives had been spent tediously pulling a tape measure and trying to read a compass wedged in awkward places in bad vis. This was the first dive where we could really take our time to enjoy the incredible cave passage. Because we didn’t need to spend as much time at depth, it was the shortest out of all of our dives on the project. Everything went well, and both of us thoroughly enjoyed the relaxing dive from Lower Orange Grove to Upper Orange Grove.

After completing the dive as planned, Justin, Grace Winfree, and I celebrated with a Luraville classic, the chili-slaw dog. While choking down the delightful eccentricities of rural North Florida, we engaged in a philosophical debate on whether the journey we had just undertaken was a traverse or a circuit. It did not fit any of the traditional definitions, and none of us had heard of anything similar in other caves. As the dogs were downed and the warm slaw dripped, it was decided upon that this novel course was most befitting of being titled a traverse. We all agreed that the new path would be known as the American Airlines Traverse; a title with a deeply personal meaning.

In Conclusion

The connection between the Crypt and Lower Orange is quite a significant one. Aside from being an enjoyable technical challenge and stunningly beautiful, it shows us that water is moving under the park in ways that we did not realize, and on more than one level. We now know there is more than one water source for Peacock Springs, and that Lower Orange Grove is taking water from both the Crypt and Upper Orange Grove. I highly suspect this water makes its way to P3, but for now that remains to be seen …

Thank you to Woody Jasper, Frank McNamara, Thai Paul, and Andrew Johnston for sharing their pieces of this story with me, and to Dive Rite for sponsoring the survey project.

DIVE DEEPER

InDEPTH: The Taming of the Slough: P3 Edition by Steve Lambert

InDEPTH: SUMP POTION #9 by Jon Kieren

Steve Lambert lives in North Florida where he works at Dive Rite and is actively involved in the exploration and survey of underwater caves with Karst Underwater Research. He frequently joins expeditions with Beyond the Sump and Hole Patrol. His hobbies include quitting when things get too hard, residential construction, and compiling Kpop playlists.