Cave

Diving Beyond 250 Meters: The Deepest Cave Dives Today Compared to the Nineties

How deep are the deepest cave dives today, compared to those three decades ago when technical diving was just getting started? InDepth editor-in-chief Michael Menduno and deep diving pioneer Nuno Gomes team up to review the history of deep cave diving, discuss the issues involved, and identify the people who are pushing our underwater envelope.

By Michael Menduno and Nuno Gomes

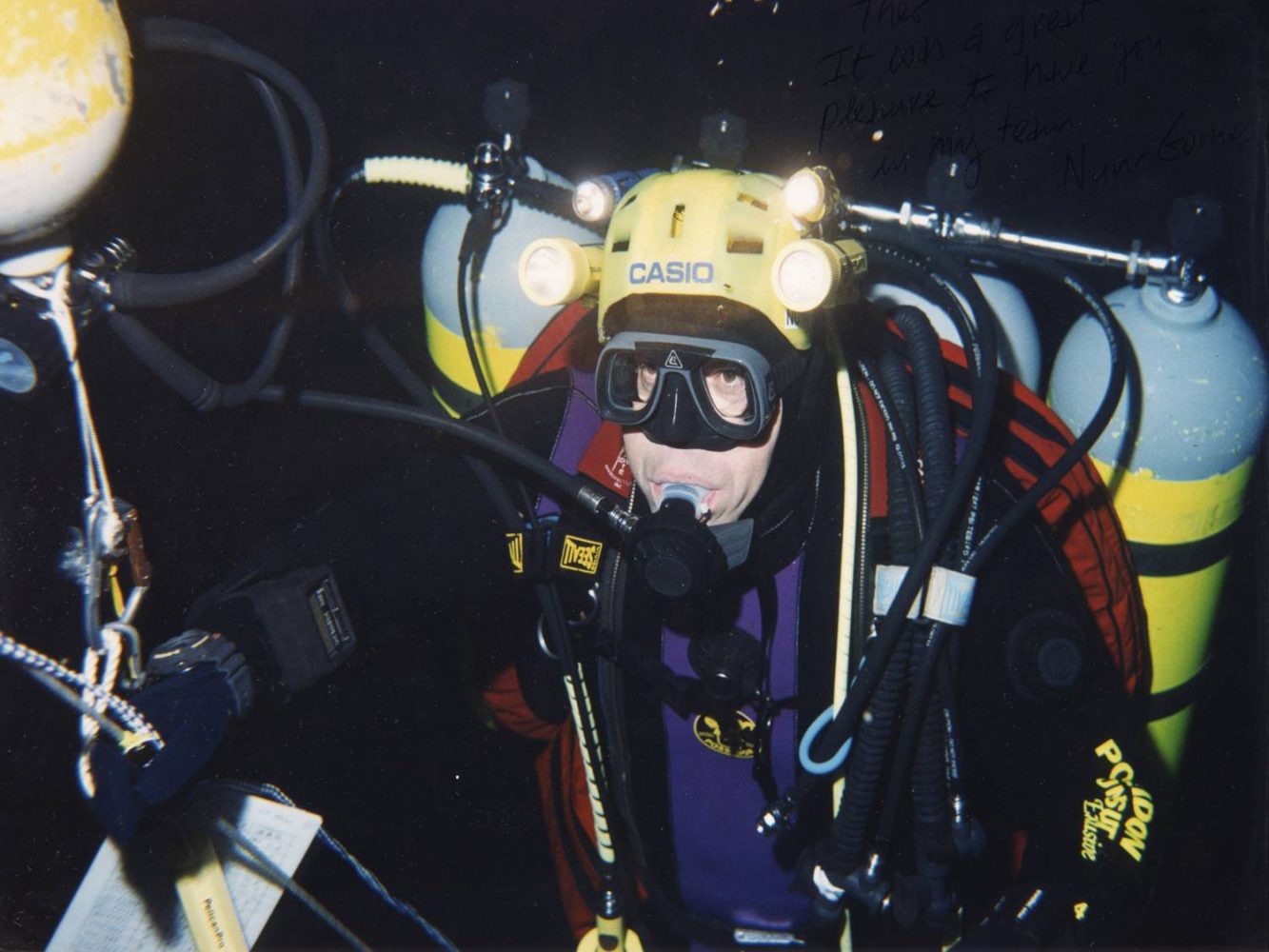

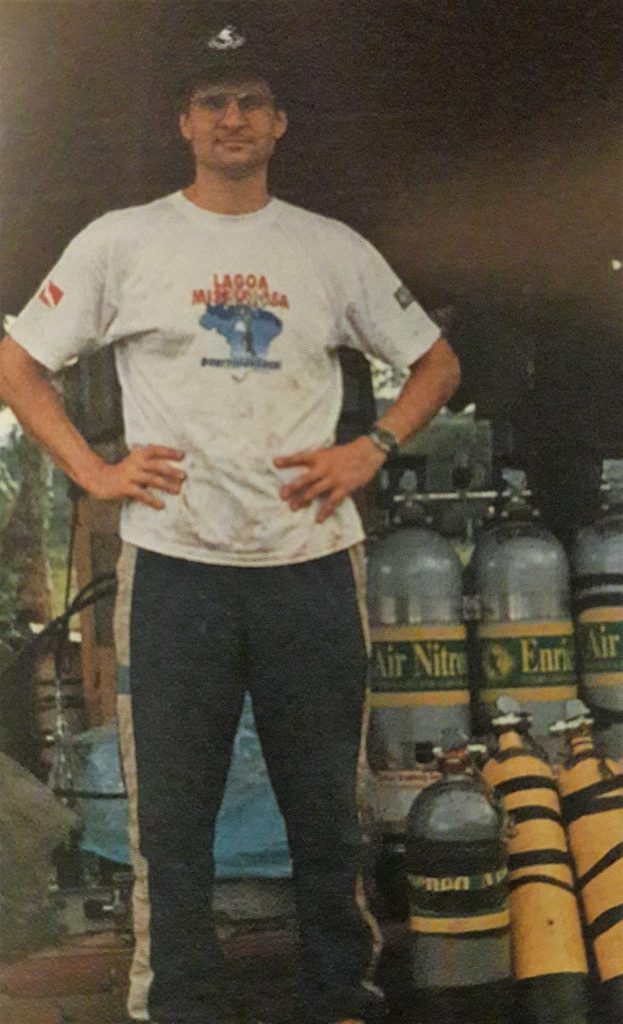

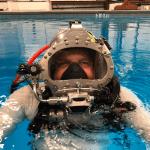

Header photo showing Nuno Gomes during his 1996 record deep cave dive at Bushmansgat. Photo by Theo van Eeden

A little more than a year ago, we ran an InDepth article, “Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives,” which compared the deepest tech shipwreck dives as of 2020 with those conducted in the 1990s when mixed gas technology was just emerging. Not surprisingly the story drew a lot of reader attention. As a result, it seemed fitting that we publish a similar article examining deep cave diving. Accordingly, I teamed up with deep diving pioneer and Guinness world record holder Nuno Gomes, who had already completed much of the needed research for his 2016 book that he co-authored with Olo Sawa, Beyond Blue: Journey Into the Deep.

Since the 1990s, technical divers have explored considerably deeper in caves than they have on shipwreck exploration dives, which is not surprising. The cave environment is far more conducive to staging equipment such as gas and scooters required for deep dives, conditions are also far more stable and rarely subject to weather compared to open water dives, and caves may also offer more psychological comfort for divers, for example, there is less sense of depth then a vertical plunge in open waters.

In addition, with the possible exception of Jacques Cousteau, cave divers were arguably the original tekkies and worked out many of the initial fundamentals of tech diving in terms of equipment and protocols. Again, likely due to the environment, they were also the first amateur diving community to begin experimenting with mix technology. In 1967, South African British Sub Aqua Club (BSAC) divers Roly Nyman [Gomes’ original cave instructor], Ian Robertson, John van der Walt and Danny van der Walt conducted the first trimix (an oxygen, helium, nitrogen mix) dive by cave divers to 107 m/350 ft in Silent Pool, in Sinoia, Rhodesia. After some unsuccessful attempts during the seventies, in 1979 Dale Sweet dived to 110 m/360 ft at Diepolder II in Florida, marking the first successful use of trimix by sport divers in the US.

Swiss diver Jochen Hasenmayer was soon to follow in 1981 with a trimix dive to 145 m/476 ft at Fountain of Vaucluse, France, using modified tables from pioneering commercial diving Oceaneering. This was the first of a series of ever deeper dives conducted by Hasenmayer, which inspired cave explorer Sheck Exley to begin his record-setting, deep mix dives.

Others, like cave explorer Bill Stone with his Wakulla Springs 1987 Project, as well Parker Turner, Bill Gavin, Lamar English, and Bill Main, who went on to form the Woodville Karst Plains Project (WKPP), began conducting mix exploration dives with the help of decompression physiologist Dr. Bill Hamilton. Similarly, in Europe, divers such as cave diving and rebreather pioneer Olivier Isler, as well as Stuart Clough, owner of Carmellan Research, who worked with British tech diver Rob Palmer, also embraced the new deep diving technology.

In contrast, the US wreck diving community didn’t begin to adopt mixed gas diving in earnest until the early 1990s, with help from tech diving pioneer Capt. Billy Deans, owner of Key West Diver, Key West, Florida—the first tech training center in the world. In fact, most wreck divers didn’t even use oxygen for decompression until the late 1980s; again, Deans was instrumental in helping the Northeast wreck diving community develop safer decompression protocols.

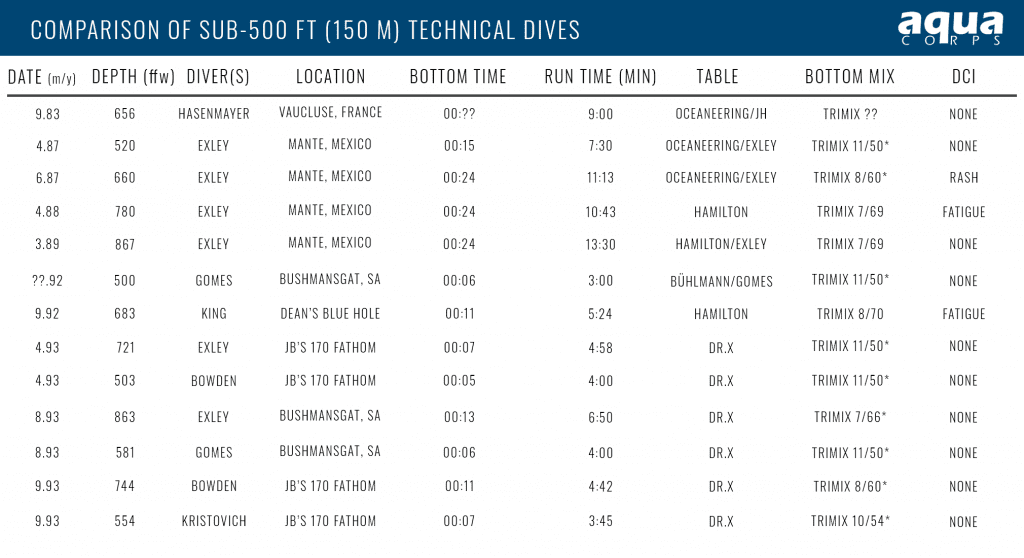

The View from aquaCORPS Circa 1993

In December 1993, my magazine aquaCORPS published reports from Sheck Exley, and Jim Bowden under the header “DEEP UNDERGROUND,” along with a table and explanation provided by Exley titled, “Comparison of Sub-500 foot (150 m+) Technical Dives,” that listed 13 known dives to depths beyond 150 meters. That table is shown below. All of the dives were cave dives conducted in fresh water with the exception of Jim King’s dive to 209 m/683 ft at Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas. Note that the listing, JB’s 170 Fathom, as it was initially called, was Zacatón, in Tamaulipas, Mexico, where Exley died in 1994.

Note that the dives were dominated by Exley, and to a lesser extent Nuno Gomes and Jim Bowden. Not listed are likely some further dives by Hasenmayer including his 1989 dive at Lake Wolfgang, Austria, where he suffered decompression illness and was paralyzed. Note also that Bowden’s partner Dr. Ann Kristovich made the list with her (woman’s) record deep dive to 170 m/554ft at Zacatón.

Decompression schedules for these dives were calculated using modified Oceaneering Tables, Hamilton’s Diving Computational Analysis Program, (DCAP), and Exley’s software program Dr. X. The table also includes some discussion of the first reported cases of High Pressure Nervous Syndrome (HPNS) by sport divers, in this case Exley and Gomes.

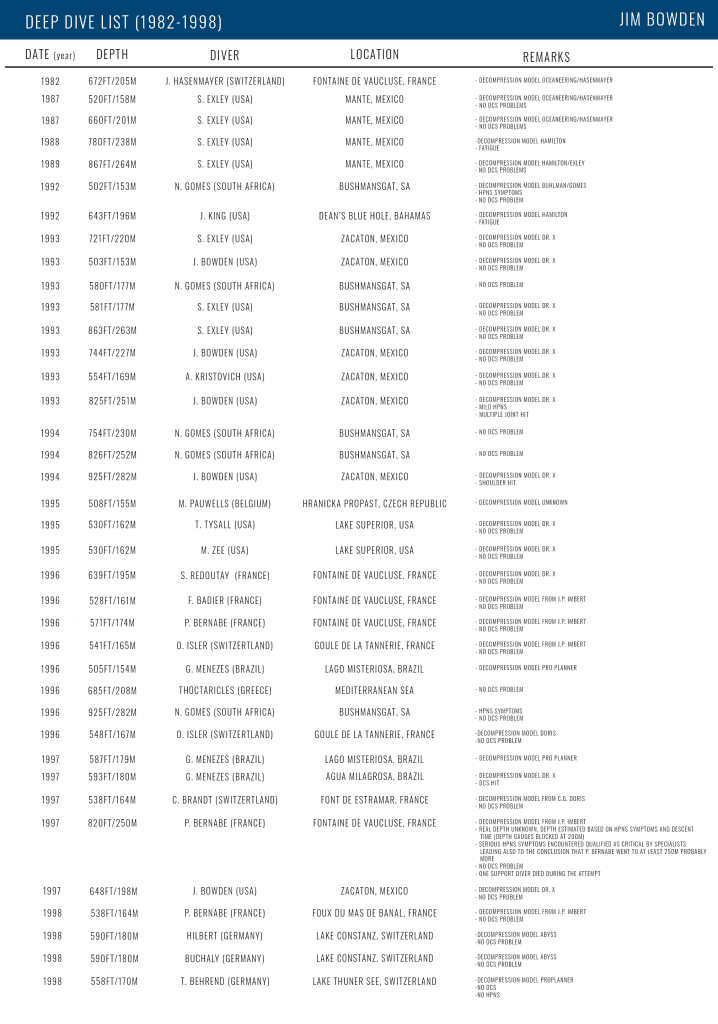

Bowden’s Deep Diving Chronology Circa 1998

In 1998, Bowden, who had conducted the deepest cave dive to 282 m/925ft at Zacatón in 1994, which was later surpassed by Gomes in 1996, compiled a chronological list of 38 sub-150 meter dives conducted from 1982-1998. Along with the table, Bowden wrote a short (unpublished) essay detailing his experience and views on deep diving, DCS, HPNS, depth calculations. We titled it, “Thoughts on Diving To Great Depths.” Bowden’s list is shown below.

All but six of the dives detailed in Bowden’s list were cave dives: there were five lake dives (one on the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald in Lake Superior, Michigan), and one dive in the Mediterranean Sea. In addition to Exley, Gomes, and Bowden, some of the new names that appeared on this list and subsequent lists as shown below are Pascal Bernabe, Olivier Isler, and Gilberto Menezes de Oliveira. Again, Kristovich remains the only woman to make the list.

Note that by 1998 several new decompression programs had gained favor by the faithful including British tech pioneer/engineer Kevin Gurr’s ProPlanner, a decompression model by French commercial decompression engineer JP Imbert turned tech diver, and the Abyss software model marketed by Chris Parrett and Joel Silverstein.

The Darkness Continues to Beckon Circa 2000

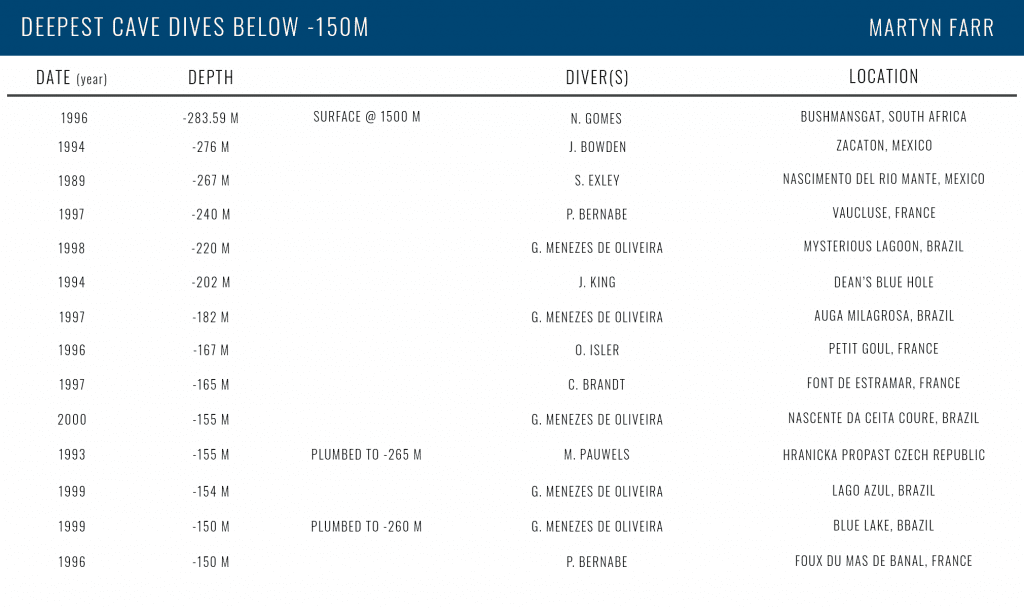

In 2000, British cave diving pioneer and author Martyn Farr published a list of the 14 deepest cave exploration dives beyond 150 m/489 ft. His seminal book, The Darkness Beckons, first published in 1980, and subsequently updated in 1991 and 2017, details the history of cave diving beginning with the early British dives at Wookey Hole. Farr’s list is shown below.

All but one of the divers can be seen on previous lists, and all of them are men. Note that five of the 14 dives were conducted by Brazilian cave explorer de Oliveira, while Bernabe claimed two of the deepest dives.

The Deepest Cave Exploration Dives Today

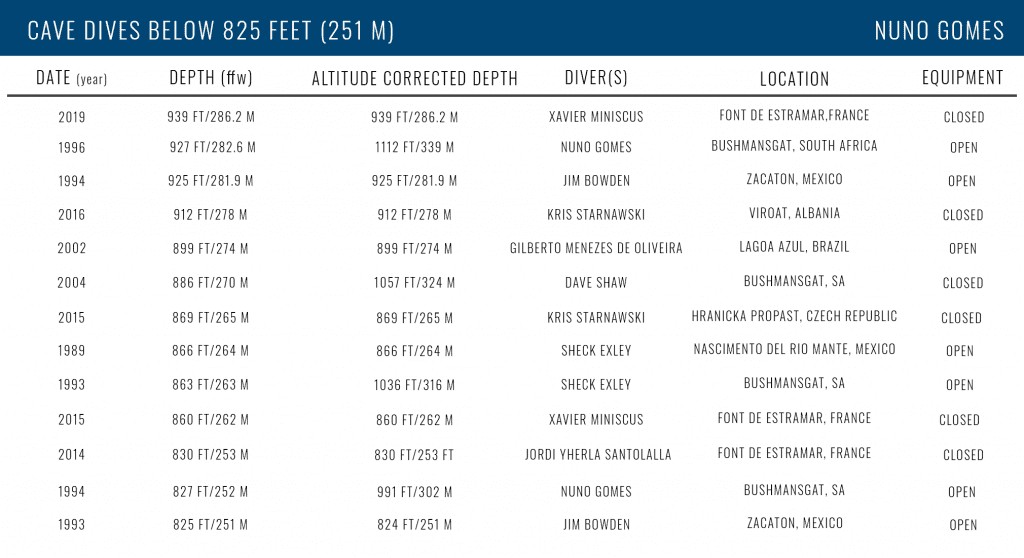

In 2016, Gomes published a list of deep dives in his book, Beyond Blue. He updated and refined the list for this article to focus on the 13 deepest cave dives, all beyond 250 m/816 ft—the new demarcation for über-deep cave dives vs. sub-150 meter dives in the 1990s. Seven of these 13 dives were conducted after the year 1999.

Note that obtaining an accurate measure of extreme depths can be challenging, especially in the cave environment, depending on the topography; divers sometimes have to rely on estimates. Few gauges are rated deeper than 200-250 meters, and even then, pressure sensors are not usually calibrated to read accurately at those depths. Gomes used an imperial Parkway gauge that went to 999 feet and then started counting again from zero. In practice today, depths are calculated using a combination of gauges, ropes, sonar, trigonometry and ROVs.

Gomes’ table is shown here and lists the dives by their nominal depth, but includes a column for altitude adjusted depth. Note that Bushmansgat is located 1550 m/5000 feet above sea level. When adjusted for altitude, Gomes’ dive was equivalent to a sea level dive to a depth of 339m/1,112 ft making it the deepest cave dive on record.

It should also be noted that all of the dives shown on Gomes’ table were solo dives (though there were support divers at shallower depths). Gomes believes that’s the only way these dives can be conducted. “It’s safer,” he explained to me. “If something goes wrong, only one diver dies instead of two.” The problem according to Gomes is that it’s not possible to save someone at these depths in the event of trouble. “You are pushing so close to the physiological envelope that you can hardly save yourself let alone someone else, if something goes wrong. You don’t have the time or the capacity, you have to concentrate on yourself,” he said.

New to the deepest cave diving list are French cave explorer and former military and commercial diver Xavier Méniscus, and Polish cave explorer Krzysztof (Kris) Starnawski. Insiders say there is a healthy competition between the two über-divers reminiscent of the rivalry between Exley and Hasenmayer back in the day. Watch this space.

Interestingly, Miniscus, Gomes, Exley, Bowden and Starnawski each account for two of the deepest cave dives, while the others on the list claim a single entry. All of the divers are still alive with the exception of Exley and David Shaw who both died conducting extreme deep dives. Spanish cave explorer Jordi Yherla Santaolalla, suffered decompression illness at deep depth during ascent from his 253 m/830 ft dive at Font de Estramar, France in 2014. He was aided to the surface by his support team and was treated for DCI.

It’s also interesting to note that in addition to claiming the deepest cave dive, Gomes set the Guinness World Record for the deepest (open water) scuba dive of 318 m/1,044 ft near Dahab in the Red Sea in 2005. Several weeks later, Pascal Bernabe claimed he set an unofficial record to 330 m/1077 ft in Corsica. Their records were supposedly bested almost a decade later by Egyptian ex-military diver Ahmed Gabr in 2014 with his reported dive to 332.35 m/1,090 ft in the Red Sea which earned him a Guinness World Record.

However, Gabr’s record remains under a cloud of doubt in the tech diving community, as evidence that suggested that he did not actually make a record dive surfaced last summer. In February of this year, Guinness announced they had investigated claims that Gabr faked his record dive, and said they found “no conclusive evidence which establishes foul play.” However, it did not address specific allegations, nor did they interview Gabr’s support team.

Not shown on Gomes’ list are the recent remarkable deep exploration dives conducted by Australia’s Wet Mules led by Dr. Richard “Harry” Harris, and Craig Challen in Pierce Resurgence. In early 2020, Harris and Chalen pushed the cave to the amazing depths of 243 m/792 feet, which fell just shy of the 250 meter cutoff. Note that Harris and Chalem dived as a team vs as solo divers. I’m sure the discussion of diving solo vs. as a team will continue as cave divers dive deeper. And we will.

Comparing Today’s Deepest Dives to The 1990s

Diving equipment has significantly improved since the 1990s, and rebreathers have become the tool of choice for deep diving, as the ever prescient Stone and Isler predicted. Six of the seven deepest cave dives conducted since 1999 were done on rebreathers; all of the 1980-1990s dives were done on open circuit.

There have been no major changes in decompression algorithms short of adding conservative factors and adapting the algorithms for constant PO2 rebreather diving.

However, Gomes pointed out that divers are breathing mixtures with far greater helium content consistent with the new research on gas density and diving safety. In addition, more attention is being paid to transitioning gases from helium to nitrogen during the ascent to avoid isobaric counterdiffusion.

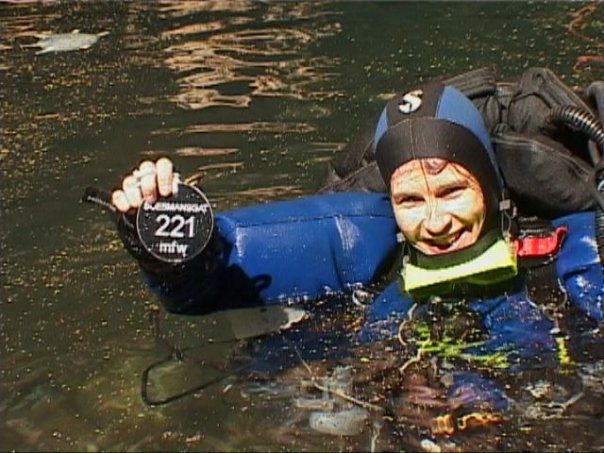

Note as of yet, no women have made the deepest dive list. Currently, Vera van Schaik, holds the Guinness World Record for the deepest scuba dive (women) to 221 m/721 feet, which she made in October 2004 at Bushmansgat, surpassing Kristovich’s record of 169 m/554 ft. Van Schaik went on to write a book, Fatally Flawed: The Quest to be Deepest, about her experience, and also wrote the forward to Gomes’ book.

Since Van Schaik’s dive at Bushmansgat, two female divers have died trying to break her record. Forty-year old French diver Brigitte Lenoir died in Dahab, Red Sea, in May 2010. Then in September 2017, 45-year old Bulgarian technical diving instructor trainer, Teodora Balabanova, died attempting a dive to 231 m/754 ft, while her husband, Mihail Balabanov, who had accompanied her, was injured.

Today, as this article is being written, one of Gomes’ students, Karen Van Den Oever is planning to dive beyond 250 m/816 ft at Bushmansgat on March 25, 2021. If she does go through with it, we plan to announce the results in the issue. [See: “South African Cave Diver Karen van den Oever Sets New Women’s Deep Cave Diving Record.”

Cave Divers Do It Deeper

How do the deepest cave exploration dives compare to those of shipwreck divers? The ten deepest cave dives today average 284 m/926 ft (adjusting for altitude and freshwater), compared to an average depth of 209 m/682 ft for the ten deepest cave dives in 2000, or approximately 75 m/245 ft deeper.

In contrast, the ten deepest shipwreck dives today average 176 m/576 ft, compared to 121 m/398 ft for the ten deepest shipwreck dives in the 1990s (see Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives). In other words, the deepest cave dives exceed the deepest wreck dives by 108 m/352 ft on average, and as a result of depth and geography are also likely considerably longer on average.

The ten deepest cave dives today average 284 m/926 ft (adjusting for altitude and freshwater), compared to an average depth of 209 m/682 ft for the ten deepest cave dives in 2000, or approximately 75 m/245 ft deeper. In contrast, the ten deepest shipwreck dives today average 176 m/576 ft, compared to 121 m/398 ft for the ten deepest shipwreck dives in the 1990s.

Will cave divers continue to push depths ever deeper over the next twenty years as they did with the last? “Xavier and Kris may push the limits a little deeper. Who knows,” Gomes told me. “However the work of breathing (WOB) becomes a problem at those depths, particularly on rebreathers.” [Note that Dave Shaw died of respiratory insufficiency at a sub-250 m dive at Bushmansgat—see video below]

Will cave divers take a lesson from the cutting edge of commercial diving and adapt hydrogen as a breathing gas for extreme depths? Hydrogen is half the weight of helium, and its slight narcotic properties have been shown to ameliorate the effects of HPNS, which is believed to be a contributing factor in Exley’s death. In fact, ambitious tech divers have already conducted an experimental hydrogen dive according to retired scientific diver of the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) John Clarke’s latest blog, “Hydrogen Diving: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly.” Interestingly enough, Sheck mentioned the use of hydrogen and hydreliox towards the end of my 1992 aquaCORPS interview with him, “Exley on Mix.”

It’s also likely that future tech divers may one day have access to lightweight, self-contained one-atmosphere exosuits, similar to what atmospheric-diving-systems (ADS) pioneer Phil Nuytten, of Nuytco Research, is building for the US Navy. Far-fetched? In 2014, British caveman Phil Short piloted an exosuit on a Woods Hole expedition in Greece to depths of 123 m/400 ft in search of the Antikythera Mechanism. It’s not hard to imagine.

I asked Sheck, a few years after his record 264 m/867 ft dive at Mante, what he thought the ultimate depth limit would be. “There is no limit,” he said. “We’ll always find a way to go deeper and deeper. That’s been the pattern all along. Ten years from now, twenty years from now, people will be doing things we’ve never dreamed of, and I see no reason for that to change.”

“There is no limit,” he said. “We’ll always find a way to go deeper and deeper. That’s been the pattern all along. Ten years from now, twenty years from now, people will be doing things we’ve never dreamed of, and I see no reason for that to change.”

Dive Deeper:

What does it take physiologically to dive beyond 250 meters? Here in this story from aquaCORPS #11 Underground XPLORERS, August 1995, we analyze extraordinary number of factors must be considered to conduct a 1000 ft/307m dive and includes Bowden’s decompression table. See: Absolutely Risky Business

By comparison, here is Nuno Gomes’ decompression table used for his record 1996 dive to 282.6m/927 ft.

What was Bowden’s motivation to bottom out Zacatón? Also in aquaCORPS #11 Underground XPLORERS, we interviewed Jim Bowden about his plan to get to the bottom of Zacatón: “I want to see the end of the cave. This one just happens to be vertical.”

You can find out more about Nuno Gome’s diving projects including his record dives on his website.

For the deepest shipwreck dives see: Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives

Video Resources: Deepest Cave Dives

World Record Cave Dive -286.2m (939 feet) 30-déc-2019 – Xavier Meniscus at Font Estramar

World Record Cave Dive – 282.6 m (927 feet) – Nuno Gomes

Hranicka Propast 265m-Kris Starnawski

Récord de profundidad de Europa en espeleobuceo-Jordi Yherla Santolalla

Pearse Resurgence 2020-Richard Harris and Craig Challen

Diver Records Doom | Last Moments-Dave Shaw

Olivier Isler : la Doux de Coly

Dean’s Blue Hole Cave Exploration by the Bahamas Caves Research Foundation 2019-Jim King

Sheck Exley Bushmansgat Cave Part 1

Sheck Exley Bushmansgat Cave Part 2

3D maps produced by DEPTHX of the Zacatón Cenote System by Stone Aerospace

Nuno Gomes Talk: Cave Diving World Records

Find your Dare: Verna van Schaik at TEDxSoweto 2013

Be sure to check out Nuno’s autobiography, BEYOND BLUE: Journey Into the Deep, which includes a lot of important cave diving history.

Michael Menduno/M2 is InDepth’s editor-in-chief and an award-winning journalist and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for more than 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.”

His magazine aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving (1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving and he produced the first tek.Conferences and Rebreather Forums 1.0 & 2.0. In addition to InDepth, Menduno serves as an editor/reporter for DAN Europe’s Alert Diver magazine, a contributing editor for X-Ray mag, and writes for DeeperBlue.com. He is on the board of the Historical Diving Society (USA), and a member of the Rebreather Training Council.

Nuno Gomes is a professional civil engineer, a CMAS technical diving instructor and a commercial diver. He was born in Lisbon, but his family relocated to South Africa during his youth. He now lives in New York, permanently, with his family. He has done all types of diving all over the world.

He used SCUBA (open circuit) to dive to a depth of 321.81 meters (1,056 feet), inclusive of rope stretch, in the Red Sea off the coast of Egypt near Dahab, in June 2005. The total dive time was 12 hours and 20 minutes. The descent took 14 minutes with two minutes spent at the bottom.

He also used SCUBA (open circuit) to dive to 282.6 meters (927 feet) in the Bushmansgat cave, in South Africa, in 1996. The cave is located at an altitude of 1,550 meters (5,086 feet) above sea level, which resulted in a decompression schedule for an equivalent sea level dive to a depth of 339 meters (1,112 feet) in order to prevent decompression sickness. The total dive time was 12 hours and 15 minutes with four minutes spent at the bottom of the cave.