Exploration

Diving Into History With Thailand’s Sira Ploymukda

Certifiable Venezuelan dive geek Carlos Lander explores the discoveries of Thailand’s underwater archeology research team headed by resident expert Sira Ploymukda, who’s been involved in at least ten shipwreck excavations. Their findings are shedding light on Thailand’s role in early transoceanic commerce.

by Carlos Lander

Lead image courtesy of Siwat Worachananant and Sira Ploymukda

Thailand is famous for its stony beaches, picturesque scenery, and outstanding dive sites, including reefs, deep drop-offs, wrecks, walls, and caverns. Most of the must-see sites are in the Andaman Sea along the west coast.

Thailand has a splendidly nuanced cultural heritage, one that has recently been explored in unprecedented depth by a new generation of marine archaeologists.

Despite what you may assume, marine archaeology is not about shipwrecks—it’s about human development. Luckily, Thailand is home to a resident expert: Sira Ploymukda, head of the country’s underwater archaeological research team.

Ploymukda (pronounced ploy-mook-da) is an expert archaeologist, who studies traditional artifacts, ports, and harbors. During his studies, he unearthed substantial evidence indicating that Thailand was a transoceanic corridor and a trans-peninsula route; his research also explores ship construction technology and its role in Thailand’s archaeological history. These subjects constitute his doctoral dissertation, the defense of which has, unfortunately, been delayed by the pandemic.

Ploymukda has also contributed to the excavations of at least ten shipwreck sites in Thailand. He was trained in the diving arts by explorer and instructor Bruce Konefe who also leads shipwreck discovery teams in the country. As the head of the field department of Thailand’s Underwater Archaeology Division for over ten years, Ploymukda has taken the time to explore and study new archaeological sites. Over time, his efforts have paid off.

Ploymukda and his team are exploring newly-discovered wrecks in an effort to determine the ranges of each particular ship based on their design, the cargo content and type, and the average payload weight in order to calculate the economic value of the cargo that was moved across cultures by these particular ships. While the Thai government is engaging with neighboring countries to publicize the importance of this academic exploration, divers are taking the lead in these research efforts. Their first major task: finding the wrecks in the first place.

Discovering New Shipwrecks

Ploymukda describes two basic methods for finding shipwrecks: active and passive. Many countries utilize satellite images to search, but sonar is more effective for exploring a specific area. Once the team has a lead on a new wreck based on sonar images, a diver or a remote underwater vehicle (ROV) is sent to verify what’s down below. This is active searching.

The second method, passive searching, happens when a village fisherman catches his net or line on the ocean floor, losing it or tearing it apart. This indicates that there is something on the sea floor that’s not supposed to be there—an object big enough to get a net stuck. At this point, an archaeologist becomes a detective.

While an archaeologist’s role is to explore, exploration is costly. So, one way to reduce expenditures is asking fishermen to report these kinds of incidents. Archaeologists or explorers gather as much information as possible from fishermen for the purpose of determining if a potential site is worth exploring (economically speaking).

In the end, there’s only one way to be sure of what’s “down there,” and that’s diving.

Once researchers decide to investigate a site, they closely guard their leads; looting is a big problem in Thailand. Since most site robberies take place in shallow waters, dive teams tend to excavate and survey sites at around 40-70 m/131-230 ft, making them more difficult for robbers to access. Ploymukda dives with a rebreather and often uses trimix (an oxygen, helium nitrogen mix to reduce narcosis) as diluent.

The site location remains confidential until all data and artifacts are collected, but for organizational purposes, it’s customary to name each wreck after the nearest port. GPS coordinates aren’t published until after excavation is complete.

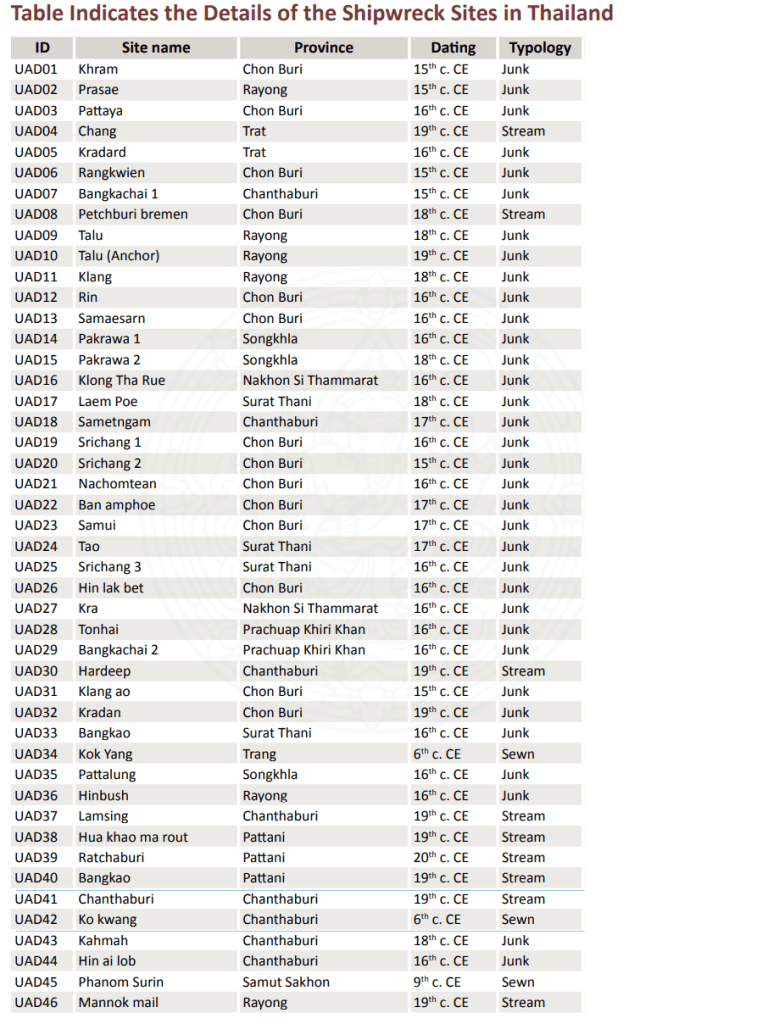

The present study includes the wrecks below:

Boots, err Fins On the Ground

Underwater archaeology is a scientific diving effort with forensic diving elements, meaning that divers must adhere to written protocols and prepare appropriately-sized teams. In general, a complete team is composed of one land team—including an officer who is responsible for all planning and contingencies—and two diving groups, one to perform the dive and the other to serve as a backup team. The backup team needs to be ready to enter the water in less than one minute in case of any emergencies.

Depending on the depth, a bottom time of 30 minutes plus decompression is customary. But, the officer is responsible for adjusting the plan based on a variety of factors, including weather conditions, currents, or depths.

Ploymukda explained that, in the past, the location of a shipwreck was manually recorded using a compass, a nautical map, and depth gauge, and wrecks were only sketched—a far cry from today’s sophisticated GPS, photogrammetry, and modeling technologies. Along with recording the specific location, divers also survey the sites, collect samples, and take measurements, videos, and photographs.

In the event that the team salvages any artifacts, they take immediate action to prevent those artifacts’ decay. Tanks of saline on the boat mimic the artifact’s familiar underwater conditions until the object is sent to a lab facility for further conservation work. Fortunately, in Ploymukda’s case, he has his own lab.

The first step in the lab is removing the salt from an artifact by putting it in distilled water. Depending on the artifact, other processes are undertaken; for example wooden findings are saturated with a wax-like material, vacuum-sealed, and freeze-dried. Then, artifacts are sent to a separate lab for dating, which is paramount to the next step: building a narrative.

Building the Story

Archaeology’s purpose is to construct a narrative: a story that fits into historical context. But, it’s not that simple underwater. Data collected from the site during a dive is integral to discovering that context, but those data aren’t the only useful tool.

Context, to an archaeologist, includes the place where an artifact was found, the soil, the site type, the layer of soil the artifact came from, what else was found in that layer, and numerous other minutiae. A shipwreck, unless it was found in a harbor, is much more difficult to put into a context than a site on land; luckily, Ploymukda’s research expertise fills in some crucial gaps.

The design of each individual ship serves as an indicator of their travel range, their cargo content and type, and the average payload capacity. These data, along with historical manuscripts or logs, are particularly important tools for cultural context identification.

The ancient peoples of the Southeast Asia region were seafarers, and they knew how to use various types of sailing vessels for long-distance voyages. But, Ploymukda and his team are trying to understand the intercultural exchange that occurred as a result of these sailing routes in the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand.

Their investigations uncovered two types of shipwrecks with distinct construction and rigging, which are integral details when determining a ship’s commercial route. Shipwrecks found were classified using ship typology, building technique, and rigging styles to pinpoint the sailing routes; once a ship was classified, the distance she could travel, the number of people she could carry and the amount of cargo she could hold could be estimated.

The shell base shipbuilding technique originated in Egypt, and was widely adopted throughout the Indian and the Pacific Oceans, as confirmed by various wreck recoveries. Frame base, however, is a technique from the east, popularly used in Chinese junk ships. Between 2008 to 2018, 46 shipwrecks were excavated in the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, and researchers encountered both the shell base and frame base in their explorations.

In addition, researchers observed different rigging techniques. Rigging refers to the system of ropes, cables, and chains that support a sailing ship. According to archaeological evidence, rigging implements have been in use in the Pacific Ocean for the past 3,000. Two rigging techniques were discovered: Lateen and Junk rigs. Lateen rigs were found in sewn boats in South East Asia. Junk rigs have been found in China; this is evidence of cultural interchange between China and Thailand.

As you can imagine, all this work takes time. Not only must researchers discover a shipwreck, salvage artifacts, and conserve them, but they also must study the wreck, associate it with a timeframe history, build a narrative theory, and test that theory. And, after all of that, many of the artifacts are sent to museums for display and further preservation.

In this line of work, you don’t just do research using books; to paraphrase Indiana Jones, “If you wanna be a good archaeologist, you gotta get out of the library.” In Ploymukda’s case, he has fulfilled that admonition entirely.

Ploymukda’s work is still ongoing. If you want to learn more about this project, you can visit the Fine Arts Department of Thailand online, where you can access the virtual museum and contribute to the project.

Additional resources:

SEAARCH: Southeast Asian Archeology, Underwater Archaeology Division (Thailand)

Ancient Maritime Cross-Cultural Exchanges

X-Ray: Ancient Wrecks Ming Pottery Wreck: Exploratory Expedition in the Gulf of Thailand

Other stories by Carlos Lander:

InDepth: They Helped Foment a Dive Computing Revolution: RIP Cochran Undersea Technology (1986-2020)

Carlos Lander—I’m a father, a husband, and a diver. I’m a self-taught amateur archaeologist, programmer, and statistician. I think that the amateur has a different mind set than the professional and that this mindset can provide an advantage in the field. I studied economics at university. My website is Dive Immersion. You can sign up for my newsletter here.