Diving Safety

Do ‘Bad Apples’ Actually Exist?

Human factors coach Gareth Lock explores and analyses the theory of “bad apples” as it applies to dive training. Are system failures the fault of individual agents or are they a result of the system in which they operate, or both? Lock’s answers and potential remedies will enlighten—he gets the core.

By Gareth Lock. Header image by Julian Mühlenhaus. Photos courtesy of Gareth Lock unless noted.

A diving instructor delivered a class in which one of the students misconfigured their equipment before entering the water. This misconfiguration led to hypoxia and the student’s subsequent drowning.

A boat caught fire during the night because of allegedly overloaded electrical circuits, and then 34 people died when they couldn’t escape the boat, despite the boat being accepted as seaworthy and general specifications being adhered to.

A diving instructor and two students died while undertaking a dive in a submerged mine system when visibility was reduced and they couldn’t follow the guideline back to the surface.

Each one of these cases is real, and each one will trigger a strong emotional response because we see, after the fact, it was likely that this event was going to happen given the conditions, actions, and decisions at the time. As a rule, we have a need to assign blame for tragedies, especially when there is loss of life, and even more especially when that loss strikes home. There is an impulse in us to hold someone accountable in light of a recognised standard of best practices, or good behaviour. And yet, at the same time, we know that those involved did not suspect they were going to die at the time; otherwise, they would have done something to prevent it.

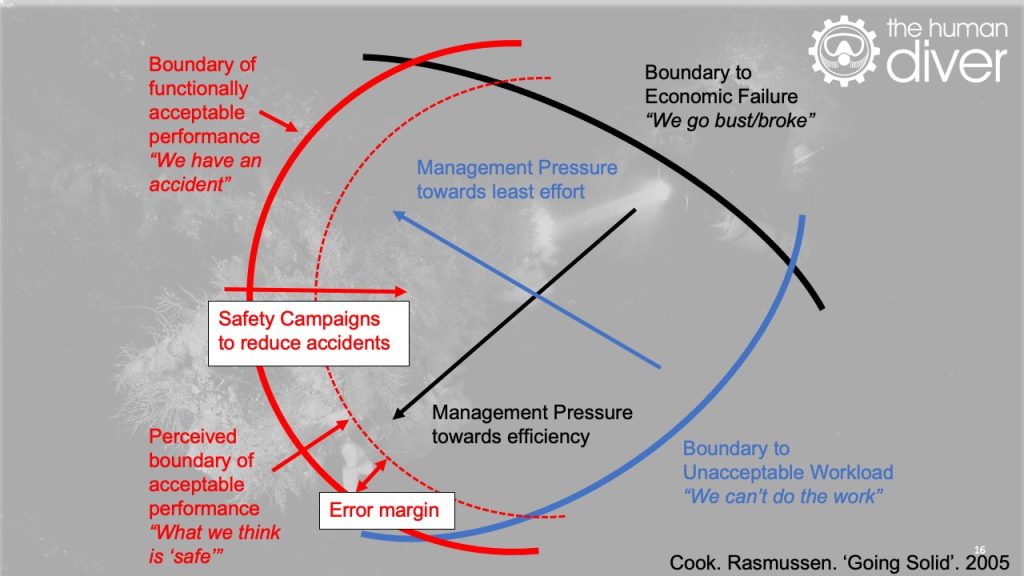

We have some degree of confidence that the participants in these scenarios were balancing acceptable performance (safety), financial viability (affordability), and workload (physical ability), which refers to resource and people rather than physical ability, and that they were managing risk and uncertainty and balancing those risks and uncertainties with the associated rewards. This tension exists in pretty much everything we do and, in the main, we are pretty good at it.

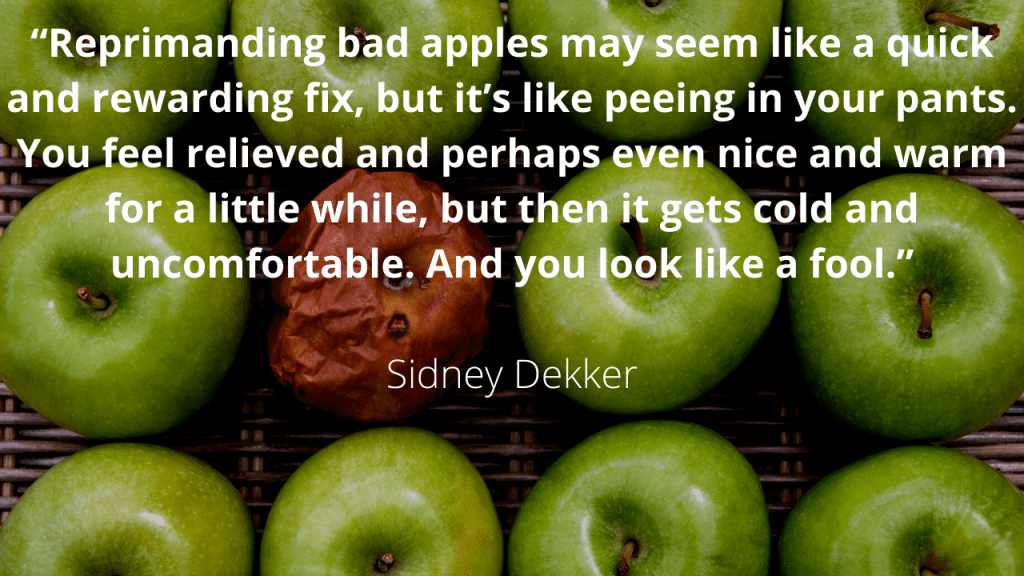

Within a system that goes right more often than wrong, bad events stick out like a sore thumb. Furthermore, when the adverse event is serious and ‘obvious’ we judge more harshly. We often believe that by getting rid of these ‘bad apples’ we can make the system safer. But as Sidney Dekker says “Reprimanding bad apples may seem like a quick and rewarding fix, but it’s like peeing in your pants. You feel relieved and perhaps even nice and warm for a little while, but then it gets cold and uncomfortable. And you look like a fool.”

These negative or critical responses are due to well-known cognitive biases, severity bias, outcome bias, and the fundamental attribution bias or error. What we often forget though is that our behaviour is a product of the system we operate in, and the choices we make in the here and now are influenced by experiences (good and bad) and the rewards (kudos, money and social media recognition) or punishments (disciplinary action, financial hardship, social media retribution) we currently face or perceive we face. The more we look into an event, the more we realize that context is so important in understanding how it made sense for someone to do what they did, or what conditions were present that increased the likelihood of the adverse event occurring.

So, where do ‘bad apples’ come from?

The term ‘bad apples’ comes from the concept that a bad apple will spoil the barrel, as such we should get rid of it before we lose the harvest. Technically, all apples will spoil eventually because of the natural decay process, even when isolated from other apples. The term bad apples has then been applied to humans in social and organisational contexts where the worry is that a single individual will corrupt others around them (from a given standard) and performance will deteriorate, or the company will go bust because of a lack of financial viability. In the safety world, ‘bad apple theory’ states that your inherently safe system remains safe as long as you get rid of the bad apples. There is a certain irony to these ideas.

There have been numerous papers looking at bad apples across multiple domains, police corruption, financial corruption, and healthcare organisations and their impact on safety and performance. In each case, the research has recognised that those individuals did not start off as ‘bad apples’, they started as well-intentioned, sufficiently-trained individuals that gradually got absorbed into the culture of the system in which they were immersed.

Many believe that individuals still need to be held accountable for their actions, and the individual bad apples haven’t been ignored in the research, e.g., Shojania and Dixon-Woods showed that 3% of doctors lead to 49% of complaints and 1% of doctors covered all complaints in a hospital. However, that paper also recognised that those individuals were a product of a failed system. At some point, disciplinary action is needed, but it should only follow a learning-based investigation and not be the first tool that comes out of the box.

The research recognizes that it wasn’t so much that the apples were bad, but rather the barrel in which they were being stored did not have the systems in place to stop the decay from developing. As such, we need to be looking more at the barrel rather than the apples if we want to make improvements to safety and performance in diving. As Professor James Reason said, “We cannot change the human condition, but we can change the conditions under which humans work.” Fundamentally, if the same ‘errors’ or ‘deviations’ keep happening at an individual level, it is likely to be a system problem, not an individual one.

Decay (drift) is normal

As divers, and being human, we all have a tendency to drift. We want to find more efficient or effective ways of getting the dive done or completing the class given the local pressures we are facing to achieve the goals we’ve set, based on previous outcomes (right or wrong). Our adherence to the rules is based on multiple factors: ease of rule compliance, fear of non-social compliance, fear of litigation, financial constraints, who wrote the rules, how much value the rules have, whether we will get caught, and what is the worst thing is that can happen.

The context is driving the behaviour. However, we should be creating an environment where adherence happens for two reasons – the rules match the environment, and those involved want to comply because they understand the value, risks, and bigger picture. Adherence should not be because those involved have to comply and are fearful of the consequences. This can lead to gaming of the system and misplaced motivation.

The normalisation of deviance, normalisation of risk, and practical drift’ (See Normalisation side box below) are all terms used to describe the slow movement away from the standards which have been decided upon, written down and published, potentially without recognition of a developing gap. Consequently, feedback is required to identify the deviations and provide corrections back to the standard, or maybe even change the standard. At the training agency level, this should be happening via the QC/QA processes, where the student provides some form of feedback to the agency about the standard of teaching and whether skills were taught or not. The problem with this is that unless the performance standards are available and briefed prior to the class, the student doesn’t know what they don’t know and won’t be able to spot drift. Therefore, unless there is a major deviation, which means that significant drift will have already occurred, drift is hard to spot.

NORMALISATION

Normalisation of Deviance is “when people within an organization become so insensitive to deviant practice that it no longer feels wrong.” Vaughan “…had found no evidence of rule violation and misconduct by individuals.” Instead, the key to accepting risk in the past was what I called “the normalisation of deviance”: Normalisation of Deviance is not about breaking rules, it is a social construct based on having standards that are gradually being eroded. This is happening because the output takes priority, and the secrecy associated with discrete or siloed operations means that other stakeholders don’t know or can’t know what else is going on. In diving, this could be the gradual reduction in hours needed to undertake training to meet a competitive advantage or the acceptance that deviations are happening and, as long as it doesn’t end up with a serious injury or fatality, it is okay. Vaughan, Diane. The Challenger Launch Decision. University of Chicago Press. Kindle Edition. Location 86.

Normalisation of Risk is the gradual process through which risky/dangerous practices or conditions become acceptable over time. In diving, these can be: reducing the amount of gas remaining at the end of a dive because nothing has gone wrong, using CCR cells beyond 12 months of manufacture because they still work, or not having a continuous line to the surface while cave diving. See: ‘Shit Happens’: The Selling of Risk in Extreme Sport

Practical Drift comes from the work of Scott Snook examining the Blackhawk shootdown in April 1994. “Practical drift is the slow steady uncoupling of local practice from written procedure. It is this structural tendency for subunits to drift away from globally synchronized rule-based logics of action toward locally determined task-based procedures that places complex organizations at risk.” See: Snook, Scott A.. Friendly Fire (p. 24). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Instructors, are you a “Bad Apple”? Check the results of our survey that we conducted with the Business of Diving Institute: Bad Apple Survey

Another dimension is the constant fear that if the student provides critical feedback to the agency about the instructor, the instructor will behave badly toward them in the future. As such, the student provides platitudes that add no value to learning. This problem is replicated at the Instructor Trainer and Course Director level. ITs and CDs drift as they are human too, but the consequences are more serious as their deviations become more widespread.

Some agencies deal with individual instructor drift by undertaking a regular check of the instructor’s performance in a live class, or by recommending co-teaching sessions where drift or variability in performance can be identified and corrected. However, we have to be careful of the ‘observer effect’ or ‘Hawthorne effect’ as well as the possibility of individuals ‘playing the game’ to pass, meaning they know how to adhere to standards but choose to cut corners when not being observed.

At GUE, [Ed. note: G.Lock is on GUE’s Quality Control board] we have worked hard over the last four to five years to change the perception of feedback within the QC forms from being something to be feared to be something that is rewarding, especially when low scores or critical comments come in. I remember when an instructor from another agency had completed their internship and taught one of their early classes, I contacted them because of a comment in the form. I wanted to understand the background behind this comment with a view to them self-improving or getting them support.

The instructor’s initial response to me was very defensive, which confused me. Afterwards, they explained the reason for their reaction was that in the past the only reason QC contacted an instructor was because there was likely to be a lawsuit inbound, and so everything had to be documented as per the standards!

If the diving industry and training agencies (barrels) want divers and diving instructors (apples) to improve, they need to provide an environment where variability in performance is visible, recognised, and not hidden. This means that there is a need for psychological safety to speak up before something happens, and a Just Culture so learning from adverse events can happen.

Unfortunately, this need is not helped by litigation and the discovery process, where anything written down can be demanded in the case of a lawsuit. For example, at the top of one of the major training agency’s incident report forms, it says, “This form is being prepared in the event of litigation.” This guidance is not likely to help anyone understand how it made sense for people to do what they did, especially if they were deviating from standards to achieve certain goals. If it isn’t written down, then it didn’t ‘exist’ and therefore can’t be produced! However, the lack of documentation makes it difficult or even impossible to detect drift. Furthermore, the lack of clear and coherent standards across the industry—and the limited visibility of these—means that it is harder to spot drift developing. Fundamentally, what acceptable standards are you drifting from?

Understanding one of the ‘bad apples’ above

The following list looks at the conditions surrounding the first event and shows how variability at multiple levels caused this tragic event.

- A number of instructors had filed complaints to their agency about the instructor involved. It is not clear what the agency did about these complaints, as nothing appeared to change in terms of the instructor’s behaviour.

- Students did not have easy access to the agency’s standards and, when located, said standards were difficult to understand and contained contradictions.

- The agency HQ staff (as with most agencies) was very small and so had limited opportunities to undertake QC checks.

- The financial margins for dive training are small, so efficiencies are found. Instructors holding multiple unit training certifications means proficiency cannot be as high when compared to specialisation. Multiple unit certification increases instructor teaching opportunities for a limited market.

- The bespoke class was based on combining multiple classes and didn’t formally exist in the manner it was being taught.

- The class schedule was constantly changing due to the availability of staff and students.

- The urgency to complete the task was driven by financial pressures for fear of handing grants back.

- There appeared to be a perception that photographic media was needed for the shop that the deceased student worked at, and the instructor was the manager/owner of that shop.

- The students in the class did not feel that they could challenge the developing situation on the boat, likely for reasons of social conformance and culture.

- There was no ‘team’ on the boat, with the perception of four students plus an instructor, rather than a learning team working together around a common purpose.

- There had been a very similar error made by the student on a previous dive two weeks prior, and this didn’t appear to have been picked up by the diver or dive team.

If we look at Snook’s definition of ‘Practical Drift’ (See Normalisation side box) we can see that over time each of the different parts of the system gradually drifted away from a standard and there was no effective check in place to bring those involved back to the expected, and possibly unclear, standards.

Opportunities for change.

The following provides some opportunities for improvement.

- If the financial viability of your dive business is struggling; you have two choices: you can cut corners and be more cost efficient, or you can fold and find another job. The problem with cutting corners is that you don’t know where the ‘accident line’ is until you step over it. Get an external view of how you teach and what margins are being eroded, and listen to that feedback. It might save you a significant amount in the future.

- If you are a lone instructor, and you do not have any form of checking performance and don’t co-teach with others, then you will very likely drift. You need to be proactive in arresting this drift by involving others and accepting feedback from them. Own the likelihood of drift.

- If you are an agency and your instructor trainers are not checked on a regular basis, do not be surprised that your instructors will not be performing at the standards they should be following. When drift or deviations occur at the top e.g., ITs and CDs, the impact at the lower levels is magnified. There is a need to create a psychologically-safe environment so that feedback is expected, can be provided, and is then shared amongst other instructors. This change starts with leaders.

Summary

There are two ways of looking at the question, “Do Bad apples exist?” in the diving industry (and life in general). One answer would be “No, they don’t exist” because everyone has the potential to be a ‘bad apple’ based on the context in which they are operating. The other way is “Yes, because at some point good apples turn bad,” but the reason they turn bad is because of the system.

Learning comes about via exploring boundaries and making ‘errors’ and reflecting on them afterwards. This ability to learn from our own and others’ mistakes is relatively immature in the diving industry—not just looking at outcomes but also at local rationality. We only have to look at social media to see the conflict and judgment that happens when an adverse event is made public. Unfortunately, we have an innate bias to look for individual fault rather than systemic weakness and often ignore the context that is driving those behaviours. This is especially true in the US with a litigious culture that looks to blame and sue, rather than learn and understand. There is a long journey ahead to improve the orchard and barrels, but we will get there more quickly if we stop focusing on the ‘bad apples’.

Instructors, are you a “Bad Apple”? Check the results of our survey that we conducted with the Business of Diving Institute: Bad Apple Survey

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 350 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture.