Diving Safety

Don’t Panic: Understanding the Causes and Remedies of Diver Panic

The “Hitchhikers Guide to The Galaxy” summarized it neatly: Don’t Panic! For good reason: taken together panic/anxiety/stress have been ranked as one the top three risk factors in scuba diving incidents. Here clinical psychologist and scuba instructor Laura Walton dives into the definition and causes of panic, explains why seeking to avoid panic can make matters worse, and offers effective strategies to consider.

by Laura Walton. Header image and photos courtesy of the GUE Archives

Panic, underwater, risks significant consequences for divers of all levels. Some research data and professional opinion lists panic as a significant factor in the majority of recreational scuba diving fatalities. Yet, the number of divers who can tell a story of the time they panicked, or almost panicked, suggests that it’s not uncommon. Avoiding panic seems reasonable. Paradoxically, however, it is a willingness to approach and understand the risks and experience discomfort may reduce the likelihood of a diver panicking. Successful progression in diving includes exposure to challenging situations that necessitate the development of effective technical and non-technical (See: The Human Diver) skills for responding to stress. Often less talked about, it is the skills to regulate cognitive and emotional reactions to problems that prevent panic. For divers seeking to improve their chances, this article highlights the more subtle processes involved in steering away from panic underwater. More experienced divers and instructors may recognize existing practices and be interested in the theoretical underpinnings.

Divers who panic underwater are at significant risk of injury or death, are unable to reason clearly, and cannot consciously control their actions. Their sole focus is to reach safety, and their erratic attempts to do so are usually ineffective and dangerous, often more so than the precipitating event that caused their alarm.

What is panic?

Panic is a physiological and psychological state that can occur when a person is—or perceives themselves to be—under severe stress. Panic interferes with thinking, information processing, and attention to one’s surroundings. It also inhibits one’s ability to consciously control their actions. Panic induces instinctive behavior, leading to survivalist actions which can be effective on land but potentially fatal underwater.

People in a state of panic are also unable to communicate effectively or respond to instructions and are unlikely to form an accurate memory of an event.

Divers are, understandably, warned not to panic. This is probably one of the least controversial opinions in diving; regardless of either one’s training or their experience level, divers will generally agree that panicking at depth can kill. While a range of barriers hamper attempts to gather data on diver panic—including the subjectivity of reporting and innate biases—various formal studies of recreational diving cite panic as a major contributor to dive injuries and fatalities (Buzzacott et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2002; Morgan, 1995). SO DON’T PANIC!

What makes a scuba diver panic?

Effective risk management for divers’ panic attacks involves understanding, addressing, and managing the factors that cause them.

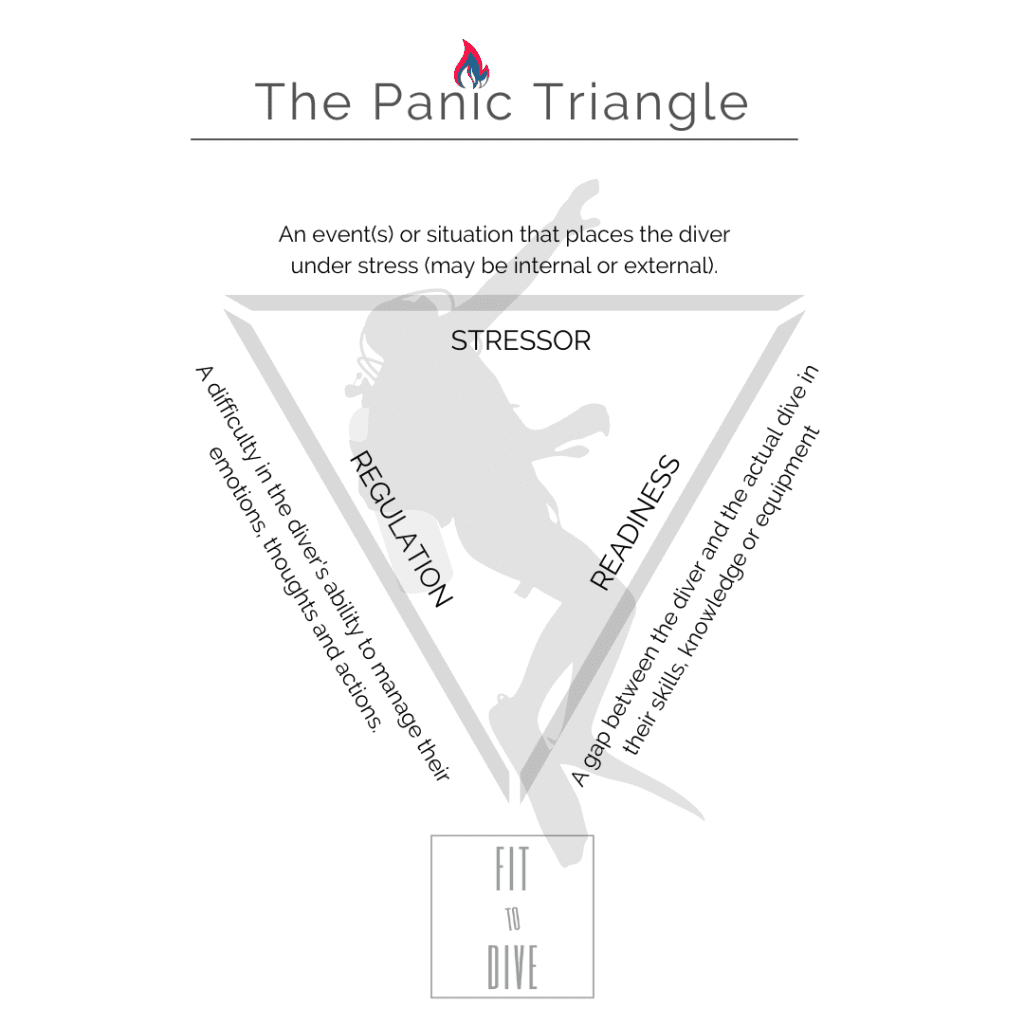

Various interacting elements can change a diver’s psychological and physiological state, potentially leading to panic. These factors are wide-ranging and can occur at any time—even long after a stressful event. This complex set of factors may be grouped into three broad areas: readiness, regulation, and specific stressor(s). Problems on all three sides of this triangle spark panic:

“A scuba diver panics when they encounter a stressor(s) that they are: (1) incapable of dealing with due to inadequate level of training, insufficient experience, or improper or deficient equipment (i.e. they lack readiness), and they are (2) unable to regulate their emotions, thoughts, and behaviours to remain sufficiently aware, alert, and stable enough to respond effectively (i.e. difficulty in regulation). In that situation, the scuba diver perceives that the situation is out of their control, the stress levels escalate, and thinking ability deteriorates. Unable to see any available solution, the brain “short-circuits,” with the primitive parts of the brain driving increasingly frantic behaviour in an effort to survive.” (Walton, 2019a)

Avoiding panic and anxiety seems reasonable, but …

Panic is not an action one can choose or not; it is an outcome that arises out of multiple precipitants, and a few drops of discomfort can quickly escalate into a panic storm. An anxious diver knows, rationally, that staying calm and solving their actual problem is the best course of action, but when that anxiety escalates into full-blown panic, the panicked diver is locked in an attempt to escape their own unpleasant experiences, so much so that they are incapable of calm and efficient action.

Oddly, evidence supports the theory that attempting to prevent panic may inadvertently lead to an escalation of the problem in both the immediate situation as well as over time. After one episode of underwater panic, the diver is often keen to avoid another. Investing time and effort into tackling the problem, one finds creative ways to move away from the internal storm of fearful thoughts and uncomfortable emotions.

Moving to prevent panic is a good thing, and reflecting upon a panic-inducing dive to develop risk mitigation strategies for the future is wise. Improving skills, upgrading equipment, and diving within more conservative limits can all help divers increase their diving safety. Yet, if these moves are made with a fixed focus on stopping the experience of panic, solution overload can increase anxiety.

Fight or flight fuels panic

A panic attack can be understood as a cycle (Clark, 1986). Fear is a precursor to panic, and frightening events trigger a cascade of endocrine and neurological processes that are intended to protect us—like the release of adrenaline and nerve signals that increase muscle tension. A fearful diver may start to worry, overthink, or distract from the unwanted emotion as their alarm grows.

This arousal state colours thoughts with anxiety, generating further neurological and endocrine signals that the body is under threat. Often aided by narcosis, hypercapnia, or both, the reaction tips into panic, a vicious cycle in which the diver becomes more stressed and less capable at an exponential rate. The person is locked in a positive feedback loop: The more they fight against or flee from their own inner experience, the more of a problem it seems, and the more distressed they become.

Entrapped by fear, shame, and guilt: how emotions take over actions

In the early 90s, Jenifer Hunt studied divers’ reactions to decompression injury (Hunt, 1993). Although she didn’t study the role of panic, her research found that shame, guilt, and embarrassment were common reactions to panic, anxiety, and a perceived loss of control. Humans generally dislike and avoid such feelings, and divers are no different.

Divers often tend to minimize instances of panic or avoid talking about anxiety in diving. But, each time divers become anxious in the future, they’ll still experience their body’s unwanted reactions, including anticipatory fear of embarrassment, also called “experiential avoidance.”

As their willingness to feel certain emotions or sensations decreases, their anxiety increases. This can be a particularly strong motivator for divers because panicking underwater is objectively dangerous, and there are very sound reasons for wanting to prevent it.

People with a (non-clinical) history of panic report higher levels of experiential avoidance and are more likely to use avoidance strategies when facing emotionally distressing stimuli (Tull & Roemer, 2007). In addition, anticipation of panic itself motivates avoidance of situations and experiences associated with a past panic episode (Craske & Barlow, 1988). For some divers, particularly novices, this may mean avoiding diving entirely. If the person continues to dive, their avoidance tactics will look very different: they will impose restrictions on who they will dive with, where they dive, how deep, or under what environmental conditions.

Again, placing such limits on oneself to avoid severe consequences is a highly sensible response to panic in diving. However, when enacted in service of experiential avoidance, these restrictions can increase the problem. When a person feels a little more in control of their feelings, they feel better—a neurochemical reward. But, further experiences of discomfort only trigger more avoidance behaviour and, as the restrictions accumulate, the diver’s “safe” opportunities decline. Eventually, they can no longer dive without encountering the unpleasant thoughts and emotions they are trying to avoid.

Entanglement in language: how our words contribute to the generation of panic

How humans talk and think about stressful events impacts their reactions to future stimuli. Language has the capacity to shut down awareness and, therefore, drive subtle forms of avoidance that can contribute to future panic.

Human beings have an awesome ability to create mental representations from verbal knowledge. Words and stories yield versions of objects and events in the mind without the need for direct experience, activating knowledge, memories, and emotions in response to personal symbolism. This ability is tremendously useful. It can support situational awareness and enhance dive planning, as well as indicate workable solutions such as practicing for potential scenarios. However, the propensity for language to create mental representations and wake up neurological networks can be problematic.

The human mind can create an imagined, mental construct about a single word. Pause for a moment and watch what your mind does with these three letters: DCI.

Three letters, a series of pixels on your screen—but do they create an image for you? A story? Connect with previous memories? Try OOG (out of gas), CESA (Controlled emergency swimming ascent), AGE (arterial gas embolism), and CAGE (cerebral arterial gas embolism).

They are just letters. But, words are symbols that stimulate verbal networks in the brain, stirring up emotions and bodily sensations in the process. We react to our thoughts almost as if they were physically tangible. Thinking about a past incident or imagining a future catastrophe can evoke as much (or more) distress than the event happening in reality.

Divers who have experienced panic underwater, or who consciously avoid it, can generate highly aversive mental and bodily reactions (often without actually entering the water!). These reactions are unpleasant, unwanted, and can drive experiential avoidance via language alone, entangling behaviours and reaffirming anxieties.

Struggling with language

Clinical psychologist Dr. Steven Hayes’s Relational Frame Theory (RFT) explores links between human language and behavior (Hayes & Hayes, 1992). RFT helps to explain the role verbal behavior plays in psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and panic disorders. RFT describes human thought and action in response to verbal stimuli. This complex theory describes the evolution of panic in all settings, including diving. For a detailed primer on RFT, check out: What is Relational Frame Theory (Part One) and part two.

“Humans can verbally construct a future and plan for it in great detail, thereby increasing the chances of survival. However, RFT also argues that derived relational responding makes verbal self-knowledge emotional and difficult”

― Barnes-Holmes et al., 2004

RFT is about how humans create relational frames between concepts using words. For example, if one dived to 37 m/121 ft in the morning at site A and the maximum depth for the afternoon dive at site B is 25 metres/82 ft, they would detect a relationship between those two dive sites: A is deeper than B, and B is shallower than A. This is a relational frame, where the names of site A and B can be verbal symbols of deep and shallow. If a third option is proposed for a site that is shallower than site A and deeper than site B, site C establishes a triangular frame. Such relational frames provide useful information for dive planning.

But what happens when discomfort or trauma is added in? If a person with no history of anxiety or panic does their first dive to 35 m/114 ft and has an unfortunate incident—perhaps they accidentally stir up silt and lose visibility—the combination of psychological stress and physical effects of gas density cause anxiety, but they manage to cope with the situation.

Their next dive is planned to 40 m/130 ft. There is a chance that hearing the depth will trigger bodily stress responses. This stress is a response to verbal stimuli—hearing the words “40 metres.” Why? There was a relational frame generated in the previous experience: 35 meters = deep = panic = “I almost died.” Our relational frame of shallow/deep then automatically connects in with another relational frame: better/worse. If 35 m = panic, then 40 m = worse panic! The low visibility may also impact this frame; the diver may learn to react strongly to low visibility through the association with panic on the first dive. The diver is now experiencing anticipatory anxiety for an event in the future that only exists in their mind as verbal stimuli.

This is partly because relational frames are bidirectional. During training, an instructor will show a student an object—a BCD, for instance—and tell them what it is called. They see the object, hear the word, and understand that the object is known by that word.

But, this phenomenon is reciprocal. Immediately, when the student is asked to put on the BCD, they can infer the word’s meaning: If the object is called a BCD, then the word BCD must mean that object. This process is automatic, unstoppable, and irreversible, so using language to escape anxiety can become a problem. What are the unstated reciprocals of each statement below? (Here’s a hint: safe/unsafe; easy/difficult; relax/panic)

“I feel safe when I am close to the guide”

“It will be an easy dive if the visibility is good today”

“When I dive with [name of favorite buddy], I can relax”

When divers encounter discomfort, they may seek to avoid the experience in the future by organising their actions according to the concepts linked in their mind: They create rules, like the statements above. Safety rules may be very helpful. But, if the function of the rules is to avoid unwanted emotions, the diver may get tangled in the reciprocal that they have unconsciously derived. When their favoured buddy cannot equalise or the visibility is not as expected, the reversed story becomes a source of anxiety in and of itself, even when nothing is actually wrong.

By unwittingly creating a neural network to signal danger if the reverse of their rules is to occur, any mental perception of rule-breaking could be enough to set off the panic cycle. Holding tightly to rules as a way to prevent panic becomes the fuel for further episodes. As anxiety increases, the rules increase and become more rigid, creating a restrictive network of relational frames. The diver is then caught up in a struggle with symbols of disaster in their own mind.

“As ideas enter a frame of coordination with “panic” then the specter of panic gets larger and larger while a person’s world gets smaller and smaller as they avoid an increasing number of things.” (Smith, 2008)

The alternative? Approach panic.

Avoiding emotions or mental images isn’t sustainable. Avoidance can sometimes be healthy; for example, sitting it out when not fit to dive. But, avoiding their own experience is exactly what causes divers to get lost in panic. When they struggle to escape panic, they spiral out of awareness into increasing emotional reactivity and a fusion with language that keeps them stuck in their own minds. The alternative to avoidance is approach: turning toward experience to become open to learning and accepting of discomfort. Drop the struggle with thoughts. Stay present in an emotional storm.

“I am not fearless. I’m alive today because I’ve learned to embrace fear …”

― Jill Heinerth, Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver

If unaddressed early, a diver’s unhelpful beliefs, thoughts, and emotions may spark panic. By creating space for uncomfortable experiences, instead of shutting down, they can retain situational awareness and more control over their behaviour. Skill at distancing from the words helps maintain calm; the awareness that a thought is a thought tends to decrease the emotional reaction. In responding with openness and space, there is more room to notice the language networks the person may be tangled in. Limiting beliefs and rules may allow a person to feel as if they are controlling stress, but, in the long-term, makes it worse.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

― Viktor E. Frankl

In the panic state, conscious choice is not an option. But, there are many moments in the seconds/minutes/hours/days/weeks/months/years before the cycle spirals when there is a choice. How divers relate to panic is a choice: approach the thought and the fear it generates to think through a useful response (e.g. problem-solve, train in necessary skills, apply risk management); or find ways to avoid the symbolic representation and the emotions it raises (i.e. worry, distract, project). Arguably, that choice makes all the difference in whether a diver is prone to panic.

Plan and make stops

Making room for uncomfortable experiences is (rather obviously) uncomfortable! It requires stopping and assessing when there is an urge to bolt. It means applying focus on the important task when one is cold, in pain, or frustrated. It calls for putting time and effort into training and practice. It demands admitting fears, communicating needs, and risking rejection. It acknowledges gaps in knowledge and seeks to self-educate, preventing panic through curiosity.

Rather than turning away from panic, it is possible to create more moments to acknowledge its precipitants and choose responses: simple pause points like taking a few minutes to stare at the sea between pre-dive checks and entering the water, setting up points on the descent to stop and offload stress while nothing else is demanding attention, or doing a bubble check of equipment to take note of any psychological leaks (Pacher et al., 2017). Panic is the end of a build-up of stress—a point of no return. The practice of pausing with a willingness to take notice creates opportunities for becoming aware of issues long before reaching the zenith of panic.

Stopping sounds easy. It’s not. A genuine pause to do nothing but be aware of one’s own state can feel vulnerable. It involves exposure to difficult thoughts and sensations. Showing up through fear is more challenging than dissociating. But, it works. Every effective way to address panic or overcome fear involves some form of exposure. By increasing the willingness to experience these, the diver regains control over their actions.

To illustrate, someone learning to clear their mask may struggle with the aversive experiences of water in their nose and fear of drowning. To avoid these uncomfortable sensations and emotions they could tough it out, mentally disconnect, use distraction to get away from the feeling—rushing to get it over with. Or, they could slow down, notice the sensations, focus on staying present, and being aware of performing the skill. In the second option, there is exposure to the sensations and emotions, and that exposure is important in allowing habituation.2 Being more willing to be uncomfortable makes it easier to become familiar with it.

Getting help to approach to panic

When someone has been stuck for a while, perhaps due to prolonged avoidance strategies or severe psychological trauma, the problem may be more entrenched. If the issue impacts the person beyond diving, it may even meet criteria for a condition such as post-traumatic stress or an anxiety disorder. Even if the problem only happens in diving contexts, there are evidence-based psychological approaches that are effective in disentangling the person from the problem.

Therapies for panic, anxiety, and trauma involve turning from avoidance to approach and will include some form of exposure. For example, in Eye-Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing Therapy (EMDR), patients ponder a distressing scenario and allow themselves to notice the unpleasant reactions they experience (while sitting safely in a comfortable chair). In doing this, the brain gradually gets used to the experience and is finally able to file it away. When the person returns to similar situations, they are no longer so reactive to the stressors and can select a more helpful state—calm, focused or confident.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapies also tend to involve various forms of exposure, such as mentally rehearsing difficult situations and practicing effective responses in the water. One of the most well-known and effective forms of addressing panic, anxiety, and phobia involves “graded exposure,” where the person gradually faces their fears by doing increasingly challenging versions of it, until it no longer causes them to panic. One of the main reasons this works is because it tackles overt and covert avoidance.

Greet Discomfort, Avoid Panic

In response to difficult experiences, shoving thoughts and emotions away temporarily works. If anxiety or panic occurs when circumstances trigger unprocessed trauma, then there is a risk of re-traumatisation. It’s like forcing yourself to run on an injured leg—the repetition of intense emotions is painful and feeds cycles of unhealthy avoidance. People can and do work through trauma without formal therapy; like bones and skin, the brain and nerves have innate healing processes. But, sometimes wounds need help to heal. Therapies for trauma and anxiety can help divers to approach panic. PFOs aren’t the only holes in the heart that can be repaired.

Panic is an outcome—an unwanted one—and an event we cannot directly prevent or choose. It is an involuntary human process triggered by various factors. Everything about diver panic—from the way it feels to the potential physical and social impacts—is aversive. So, it’s natural to avoid all its aspects. To prevent panic in scuba diving, one needs to be more willing to be uncomfortable—to be less concerned with getting soaked in the precipitants in order to retain focus on finding solutions.

Panic Survey: Please help us to better understand the experience of scuba divers with panic, and answer questions raised this article by Dr. Laura Walton. Please compete the Panic Survey here.

Footnotes

- Behaviourism is a traditional school of psychology that explains all behaviour in terms of stimulus and response; i.e. what we do is learned via interaction with the external environment. Traditional behaviourism virtually ignored the role of human thought and language and was considered flawed for this reason.

- Habituation: innate reactions to a stimuli decrease when the stimuli is given frequently. For example, the strong reaction to breathing underwater for the first time lessens as we get used to it.

References

Barnes-Holmes, Y., Barnes-Holmes, D., Mchugh, L., & Hayes, S. C. (2004). Relational Frame Theory: Some Implications for Understanding and Treating Human Psychopathology. In International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy (Vol. 4, Issue 2).

Buzzacott, P., Rosenberg, M., & Pikora, T. (2009). Using a Delphi technique to rank potential causes of scuba diving incidents. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine, 39(1).

Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behavior Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461–470.

Colvard, D. F., & Colvard, L. Y. (2003). A Study of Panic in Recreational Scuba Divers. Undersea Journal,

Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (1988). A review of the relationship between panic and avoidance. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(6), 667–685.

Davis, M., Warner, M., & Ward, B. (2002). Snorkelling and scuba diving deaths in New Zealand, 1980-2000. South Pacific and Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS) Journal.

Hayes, S. C., & Hayes, L. J. (1992). Verbal Relations and the Evolution of Behavior Analysis. American Psychologist, 47(11), 1383–1395.

Hunt, J. (1993). Straightening out the bends. aquaCORPS.

Morgan, W. P. (1995). Anxiety and Panic in Recreational Scuba Divers. Sports Medicine, 20(6), 398–421.

Pacher, A., Cleveland, S., Muth, T., & Schipke, J. (2017). Fatal Diving Accidents in Alpine Waters: A Series of Triggers Leading to Disaster? Austin Sports Medicine, 2(1), 1014.

Smith, S. T. (2008). What is Relational Frame Theory (Part Two). Ironshrink.

Tull, M. T., & Roemer, L. (2007). Emotion Regulation Difficulties Associated with the Experience of Uncued Panic Attacks: Evidence of Experiential Avoidance, Emotional Nonacceptance, and Decreased Emotional Clarity. Behavior Therapy, 38(4), 378–391.

Walton, L. (2019a). Panic Triangle: What makes scuba divers panic? – YouTube. Fit To Dive Youtube .

Walton, L. (2019b). PREVENT PANIC in Scuba Diving. In Fit To Dive.

Additional resources:

Undercurrent (2003) survey of more than 12,000 divers: Panic in Recreational Scuba Divers

Alert Diver.Eu (2011): Psychological reactions and scuba diving, description of a treatment by Maria Luisa Gargiulo

Alert Diver.Eu (2015): No Panic, we’re Divers! by Andreas Aceranti and Simonetta Vernocchi

What does the absence of panic in face of extraordinarily stressful circumstances look like? Here WKPP co-founder and explorer Bill Gavin reports on a freak incident that resulted in the death of WKPP co-founder and explorer Parker Turner. The report was mandatory reading for Capt. Billy Deans mixed gas courses in the early 1990s: The Incident Report at Indian Springs by Bill Gavin

Check out Dr. Walton’s online course:

Laura Walton is a Clinical Psychologist and scuba diving instructor bringing together psychology and scuba diving to help people with their diving. She provides specialist psychological services for scuba divers in the UK and widely accessible online courses. Laura has been guiding and teaching scuba diving in the UK since 2012 and is currently a PADI Master Instructor at The Fifth Point Diving Centre, Blyth, UK. Find her blog here: Fit To Dive Blog.