Diving Safety

Drift is Normal. Being a Deviant is Normal. Here’s Why

What causes individuals and organizations to drift from acceptable standards and behavior? Is it an aberration or something to expect, and what can we do about it? Human Factors coach Gareth Lock takes us for a deep dive into human biases and our tendency to drift, and what that means for human performance.

by Gareth Lock

Header image: a deviant diver on the SMS Cöln, and other pictures courtesy of Gareth Lock, unless noted

In 1994, two US Army Black Hawk helicopters were shot down by two US Air Force F-15 fighter jets over northern Iraq killing all 26 people on board the choppers. When the story hit the media, it was almost unbelievable that two highly professional aircrews being guided by other equally professional operators on the Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft could mistake the Black Hawk helicopters for Mil Mi-28 Hind helicopters. But they did!

In his excellent book Friendly Fire: The Accidental Shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq, Scott Snook developed and demonstrated the concept of practical drift, a theory whereby each sub-organisation or team has a certain amount of leeway to undertake their operations. This flexibility acknowledges that you can’t follow the rules exactly to the letter all the time. The problem is that these small deviations compound across the wider system with potential disastrous results; and, importantly, no one appears to recognize that the drift is occurring. Snook’s event map describes a complicated web of relationships between multiple stakeholders—the tasking organisation, the aircrew in the Black Hawks, the F-15 aircrew, and the AWACS control team—all of whom were doing the best they could with their limited resources and quickly changing circumstances.

Practical drift is similar to the “Normalization of Deviance,” a concept Diane Vaughan developed during her examination of the Challenger Shuttle disaster. Vaugn explored the idea in her 1996 book, The Challenger Launch Decision – Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA. Normalization of deviance has been discussed in a number of recent diving blogs in an attempt to explore the acceptance of the (continued) breaking of a single rule.

Rather than focus on a single rule, we should consider Vaughan’s definition wider than the individual level, and look to a larger scale. “Social normalization of deviance means that people within the organisation become so accustomed to a deviation that they don’t consider it as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceed their own rules for elementary safety.” Neil Richardson, a safety and human factors professional (and colleague of mine) operating primarily in the aviation domain, offers another perspective while addressing the same point: “The Shuttle programme was risk-managed right up until the point it wasn’t and the Challenger and crew were lost.”

Risk management vs, uncertainty management

Risk management is often mentioned in the “professional” arm of diving and diver training courses—such as dive master, instructor, and instructor trainer courses—but it is rarely covered in detail during “user” courses or sport diving. Despite this lack of formal content and process, we are constantly managing relevant uncertainties with the goal of providing an enjoyable dive for ourselves and our students and reducing the likelihood of having an adverse event.

The term “uncertainties” has specifically been used instead of “risk” because of the way that we normally make decisions in an uncertain environment. When managing risk, we are often comparing historical analyses of quantitative data to determine likelihood and consequence using the logical or System 2 part of the brain. However, when we are managing uncertainties, we use a different part of the brain—often described as System 1—which relies on pattern matching, cognitive biases and mental shortcuts. Importantly, System 1 is heavily influenced by our emotions, which is why we often react quickly rather than logically.

Equating “risk” and “uncertainties” is like conflating the “apple” type of decision-making with the “orange” type of decision-making. They are both decision-making concepts, but they have different processes and applications and can lead to different outcomes.

We need to recognize that the uncertainties we deal with while diving aren’t just focused on physical safety/harm, but also cover legal, reputation, financial, psychological, and social uncertainties and their associated outcomes. Research has shown that the fear of psychological harm can be stronger than the fear of physical harm.

In the diving industry, when something goes wrong, the (social) media and “investigations” often focus on the proximal causes—those that are closest in time and space to the event—of what happened. There is a focus on violations, rule-breaking, human error, recklessness, or direct health issues, and only sometimes do supervisory/instructional factors come into the discussion. Furthermore, the media rarely examines “local rationality” (why it made sense for the individual to do what they did) or the immediate or wider organisational and cultural factors that may have been present.

Local rationality

If we focus on the local rationality to start with, we know that the majority of the time we are operating in System 1 mode, which is fast, intuitive, and pattern-matching based thinking. We are not actively paying attention to everything that we’re sensing; instead, we are picking what we think are the relevant or important factors based on our previous knowledge and experiences, focused by our present goals and expectations, and using those elements of information to make a decision.

Despite what some would think, you can’t pay 100% attention all the time! This means that we are literally ditching billions of bits of sensory data each day because, in real time, we don’t think those bits are relevant or important. When there are pressures that prevent us from being more thorough, we are trying to be as efficient as possible. These pressures might be related to time, money, peer-pressure, fear of failure, fear of non-compliance, or fixation on goals/outcomes. However, the more we get “right” without thinking about all of the incoming stimuli, the more we use this pattern to reinforce our decision and then repeat it. How often have you heard “We’ve always done it this way?”

Maybe an adverse event would provide a learning opportunity? Unfortunately, the likelihood of adverse events serving as cautionary tales is entirely dependent upon biases in our thinking and how those biases inform our interpretation of an event, adverse or otherwise. The following is a list of biases:

- Outcome bias describes the tendency to judge serious events more critically than minor events. This is because we disconnect the quality of the outcome from the quality of the decision. For example, those involved in a fatality with the same conditions as a non-fatality will be treated more critically; a poorly performing regulator that free-flows in 10 m/33 ft of cold water will be treated differently from the same regulator that free-flows in 40 m/131 ft of cold water because the consequences are more severe.

- Fundamental attribution bias is the tendency to attribute causality of an adverse event involving someone else to the individual involved rather than the situation or context. This is different to when we personally experience failure, as we often blame the situation or context! Inversely, when we personally experience success, we look at our skills and behaviors; but, when others succeed, we have a tendency to attribute the “opportunities” they had as the cause for success.

- Distancing through differencing is the tendency to discount failures in others as being relevant to ourselves because we are different to the other party in some way, even if the general conditions and context are the same. A recreational OC diver may forget part of their pre-dive sequence because they were distracted but an experienced OC technical diver may believe that they wouldn’t make that same mistake, even though the conditions were the same.

- Hindsight bias is the tendency to think that, if we had been in the adverse situation, we would have known at the time what the adverse event would have been and would have responded differently. Part of this is because we are able to join the dots looking backwards in time, recognising a pattern that wasn’t apparent in the moment.

Rewards

As a result of these biases, we aren’t very good at picking up small deviations in procedures because we experience “good enough” outcomes, and we are “rewarded” for gradual erosion of the safety margins that the original standards were created to address:

• We saved time (or weren’t late) as we skipped through the checks quickly.

• We saw more of the wreck or reef because we extended the bottom time and ate into our minimum gas margins.

• We managed to certify a few more students this month which helped pay the bills, even though we didn’t cover everything to the same level of detail that we normally do.

• We got some really great social media feedback because we took those divers somewhere they hadn’t been before—and shouldn’t have been either—but they loved it.

Rewards come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, but the common factor is the dopamine rush: Our brains are wired to favor the feel-good rush of a short-term gain over the prolonged reward of a long-term gain. On the other side of the coin, we are also willing to sacrifice a potential major loss in the future if there is a guaranteed minor loss now. For instance, imagine that you’re entering the water for the “dive of a lifetime” in cold water with a regulator setup that doesn’t breathe too well. You weren’t able to get it serviced because of time/money issues. At the end of this particular dive, you have to do a gas sharing ascent; someone else was out of gas due to an equipment failure, and both of your second stages freeflow and freeze, due to poor regulator performance, increased gas flow and the cold environmental conditions. This resulted in two people who were now out of gas and making a rapid ascent to the surface.

In hindsight, we can see where the failures occurred. But, in real time, the erosion of safety margins and subconscious acceptance of the increased “risk” are likely not considered. In mid-July 2021, I gave a presentation to Divers Alert Network Southern Africa (DAN SA) on the topic of setting and maintaining goals and how goal focus can reduce safety.

Organisations drift too

This article opens with the topic of normalization of deviation as it related to NASA and the Challenger Shuttle loss. The gradual, imperceptible shift from an original baseline through a series of “risk managed” processes and activities resulted in a “new” baseline that was far from acceptable when considering the original safety argument. This isn’t the first time an organisation has drifted, nor will it be the last.

Organisations are made of people, and there are reward systems in place within organisations which lead to a conflict between safety, workload, and financial viability. The image below from Jens Rasmussen shows this tension and the “safety margins” that are perceived to be in place. The difficulty is that we don’t know how big the gap is between the margin and catastrophe, so we keep pushing the boundaries until we get some feedback (failure) and hope that it isn’t catastrophic.

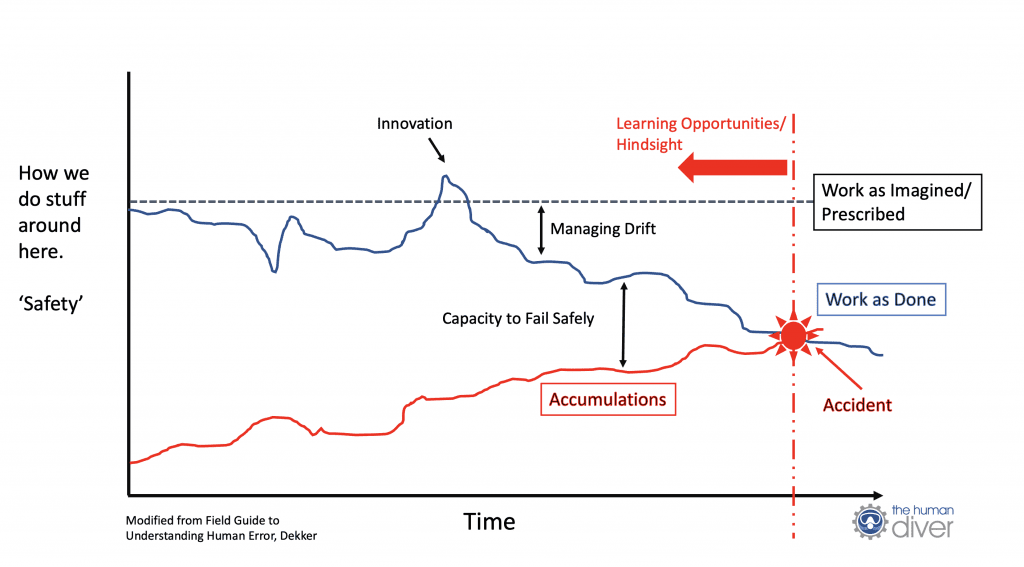

Another way of looking at this tension and drift is to use a framework from the Human and Organisation Performance (HOP) domain called the Organisational Drift Model from Sidney Dekker.

The premise here is that safety is “created” by the development of rules, processes, procedures, and a culture which supports adherence to these standards or expectations. In the modern safety domain, these rules, processes, and procedures are called “Work as Imagined” or “Work as Prescribed.” They rarely match exactly the operational environment to which they are going to be used. There are good reasons for that; you cannot document everything that you want your people (instructor trainers, instructors, dive masters, and divers) to do in every circumstance, so there will be gaps between what should be done and what is done. These gaps are filled in by experience and feedback. Some call this common sense, but you can’t develop common sense without personal experience!

As time progresses, there is an increased gap between the “Work as Imagined” (black line) and “Work as Done” (blue line). This gap is risk or uncertainty to the organisation. Not all drift is bad though, because innovation can come from drift as long as it is recognized, debriefed, and intentionally fed back into the system for improvement.

At the same time as individual and team performance is drifting, the operational environment is changing too. There are accumulations which are adding uncertainty/risk to the system: old or outdated equipment, external requirements changing, legislation changes, change of purpose of equipment or accommodation/infrastructure, and many others. Often these accumulations are dealt with by different people in an organisation, so the compounding effect is not seen.

The gap between “Work as Done” and the “Accumulations” line is known as capacity within the system. This capacity is managed by individuals, taking into account their experience, knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards and within the diving environment. Safety does not reside in paperwork, equipment, or individuals; it is created by those within the diving system taking into account all of the resources they have and the pressures they face while balancing workload, money, and safety dynamically.

However, when the capacity runs out (when the Work as Done line crosses the Accumulations line) an adverse event occurs. This event is now under the spotlight because it is obvious and cannot be hidden, especially if it is very serious. Hindsight clouds our ability to learn because we think the gaps must have been obvious. Effective organisational learning to prevent drift doesn’t need an adverse event. What it needs is a curious mind and the motivation to improve. If we stopped time 5 seconds before the lines crossed, while we still had capacity, then all of the learning opportunities would still be present and we could examine them. We would be able to see what accumulations are occurring, we would be able to see Work as Done actually was, and we would be able to increase the capacity of the system thereby reducing the likelihood of an adverse event. But that requires organisations to recognize that adverse events are outcomes from a complex system with many interactions, and where they set and demonstrate the acceptable standards and expectations. The absence of adverse events does not mean that you are operating a ‘safe’ system.

If drift is normal, what can I do about it?

First, recognize and acknowledge that drift exists. We all have a tendency to drift. If drift is occurring, look at the conditions that are causing the drift without focusing on the drifting individual themselves. This could be time pressures, financial pressures because of ‘cheap’ courses, lack of experience, high turnover of staff and low commitment to the sport by divers or dive professionals.

Secondly, create an environment where feedback, especially critical context rich feedback, is the norm. This has multiple benefits:

- Individuals find out where they are drifting from the standards/expectations which have been set.

- Organisations find out if their standards/expectations are fit for purpose and where issues about compliance are arising.

- Accumulations are identified in a timely manner and addressed.

There are a number of blogs on The Human Diver website and our Vimeo channel which help to develop a learning culture, understand how drift occurs via human error, and how to develop both a psychologically safe environment and a Just Culture. In terms of having an immediate effect, a post-dive/post-project debrief is one of the best methods, and you can download the DEBRIEF framework I created to help facilitate critical, learning-focused debriefs from here: www.thehumandiver.com/debrief

Remember, is it normal to err. It is what we do once we’ve made the error that matters when it comes to creating positive change in the future. If we focus on the individual and their behavior, things are unlikely to improve. However, if we look at the conditions and context, then we have the opportunity to reduce the chances of an adverse event in the future. And if we share those lessons, it isn’t just our organisation or team that improves, the diving community can too.

Dive Deeper

Be There or Be Deviant: HF In Diving Conference 24-25 September 2021

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 350 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and a Just Culture. In September 2021, he will be opening the first ever Human Factors in Diving conference. His goal: to bring human factors practice and knowledge into the diving community to improve safety, performance, and enjoyment.

\