Cave

Exploration of Weeki Wachee 2019-20: The Search for The Source Continues

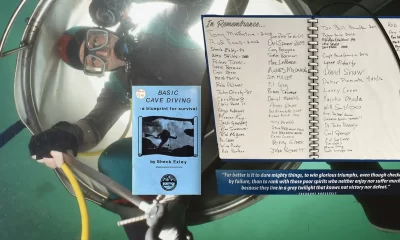

Karst Underwater Research (KUR) divers have just finished up their 2019-2020 season, plumbing the depths of Weeki Wachee Springs, which is now the deepest cave system in Florida. KUR director, Charlie Roberson, has the deets.

By Charles Roberson, Karst Underwater Research

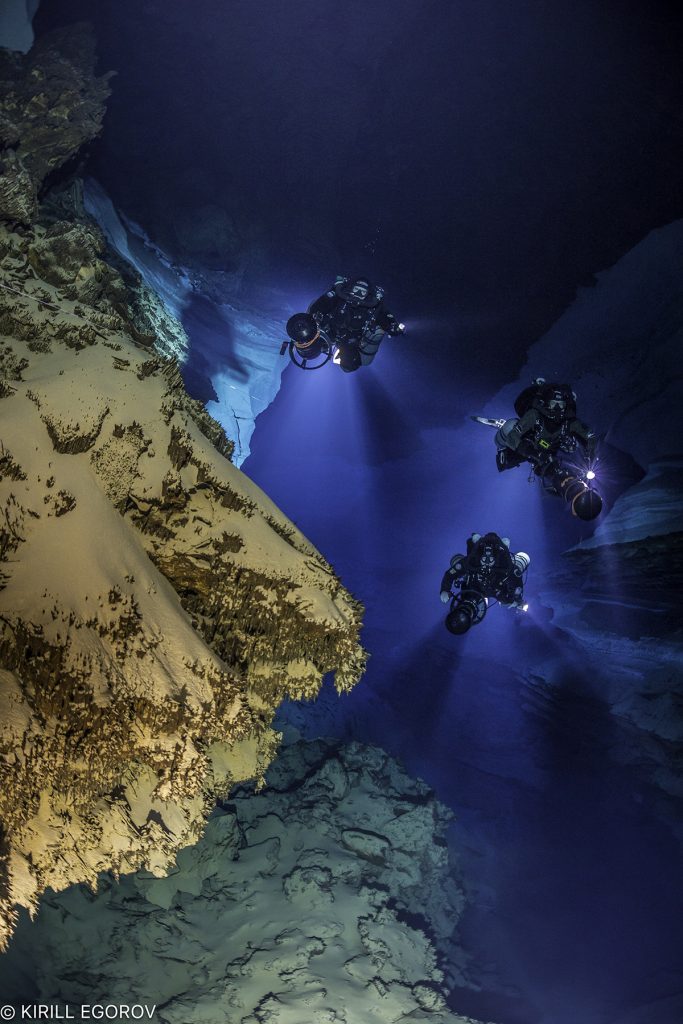

Header photo by Kirill Egorov

Note: depths are shown in meters of freshwater (mfw) and feet of freshwater (ffw).

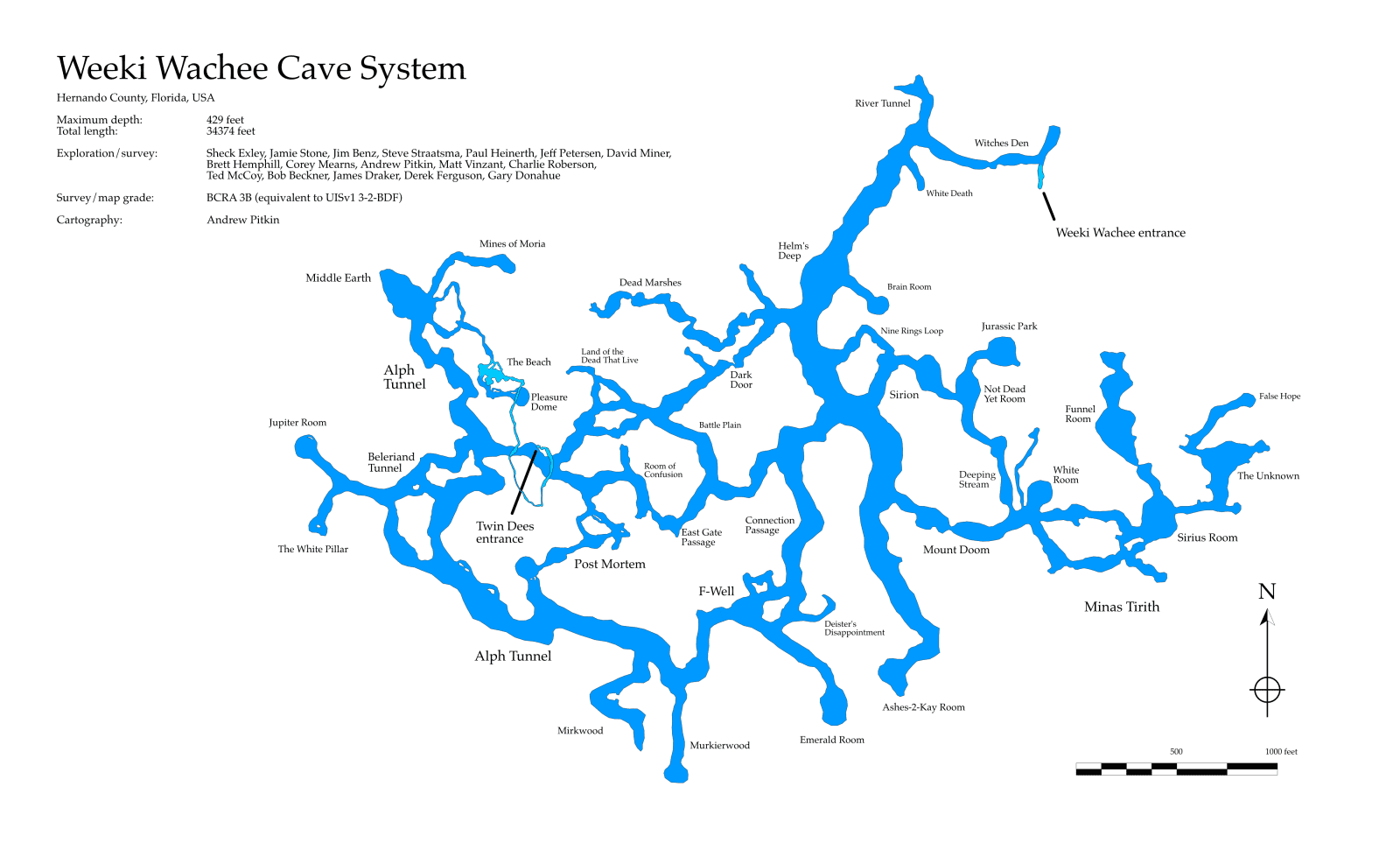

Karst Underwater Research (KUR) has a long history of exploration in Weeki Wachee cave system. Dives are conducted under a research permit from the Florida Park Service but the dive season is governed by the rise and fall of the local water table. The main spring entrance is only accessible during severe drought periods, but ever since Twin Dees (aka Little Spring) was connected in 2014, we have had safer and more reliable access to the system. Unfortunately, it’s not accessible at all times. When the groundwater rises beyond certain levels, the entrance shaft at Twin Dees becomes dangerous due to the high flow. Conversely, when the groundwater drops below certain levels, Twin Dees ceases to flow enough water to provide adequate visibility. It’s during the in-between periods of neither drought nor flood that Twin Dees allows divers to safely access the Weeki Wachee cave system.

Last dive season ended in the spring of 2019 with a significant new discovery. Karst Underwater Research (KUR) President Brett Hemphill had spotted a lead on the southeast wall of the White Stripe room during a video dive. Unable to dive for the next month due to work commitments in Palau, Brett gave fellow KUR directors Andy Pitkin and Matt Vinzant his blessing to explore this newfound lead. What Andy and Matt found was a whole new section of cave with significant flow. Not only did this section have flow, but it was also some of the deepest in the system with most passages below 110 mfw/ 360 ffw. Could this be the elusive water source for the entire system? In keeping with the Tolkien theme, they named the section Minas Tirith after the city of Gondor.

The team had to wait until the rains raised the groundwater levels and increased the flow in the small Twin Dees entrance. Conditions started to look promising during the summer, and the team undertook several setup dives to prepare for renewed dive operations. However, the summer rains raised the water levels faster than expected, and the window quickly shut due to high flow.

It wasn’t until December that the team was able to renew dive operations. On December 7th, Andy and Matt returned to the Minas Tirith section and pushed the end of their previous line. They continued approximately 168 m/550 ft into a large funnel-shaped breakdown room. Unable to find an obvious going passage, they fell back to a lead that Matt had spotted on their previous dive. This lead was located about two-thirds of the way into the Minas Tirith section on the southeast wall of a massive room that Pitkin’s son Miles named the Sirius room. The lead at the base of the room was at 113 m/370 ft and quickly led to another discovery that Matt dubbed the Unknown. The Unknown was actually two rooms conjoined in the middle. The first room was nearly vertical breakdown with a large window at the top opening to a shallower second room. Both rooms were large enough that it was nearly impossible to see both walls despite the clear, blue water. The team continued along the right wall of the second room into a small alcove they called the Attic, adding a total of 229 m/ 750 ft into the Unknown.

While the exploration team was underway, Brett Hemphill installed a new habitat in the fissure at 21m /70 ft. This habitat is suspended by bolted anchors and has two seats for divers. As our dives grow longer, this habitat will get us out of the water sooner, allowing us to do our 21-15 m/70-50 ft stops warm and relatively dry. The plan will be to run a habitat scrubber in this habitat the same as we currently do in the 12 m/ 40 ft habitat.

On December 14, Bob Beckner, Derek Ferguson, and Gary Donohue explored and surveyed 255 m /835 ft of passage that they named the Battle Plain. This large passage connects several of the short-cut passages together and has an average depth of 100 m / 330 ft.

Into The Unknown

A week later, Brett and I set off to explore the Unknown. On the way, we plugged in a battery pack and turned on the radio location ring that Andy and Matt had dropped at the top of the breakdown in the Sirius room. With the red LED indicating that the ring was transmitting, we headed down into the passage leading to the Unknown. Almost immediately we came to the bottom of a large breakdown with what appeared to be a lead to the right. Brett went partially into this lead and came back to tie in. As he was doing that, I went further in the lead since I was going to bird-dog out in front.

Unfortunately, as I went further in the passage, it became apparent that it ended in a room with an unique bowl-shaped floor. I quickly headed back and signaled Brett before he tied in his reel. We decided to head up into the Unknown and quickly followed Andy and Matt’s line into a small alcove with even smaller going passage, and we decided as they did that there were other more promising leads to be explored first. When you’re exploring a deep cave with multiple leads, you have to triage and go with the most obvious first, giving preference to the direction you think the cave is heading. This doesn’t always work out, and I’m sure we’ve overlooked some important passages.

As we came out of the alcove, I scootered across the huge room to see that there was a deeper-looking passage on the other side. I signaled Brett to tie in, and as he did I dropped down to make sure this wasn’t an alcove at the bottom edge of the breakdown. At first I wasn’t so sure, but as I descended below the duck-under I saw a cobalt blue passage with a white floor and walls reminiscent of the Post Mortem passage. These slightly smaller, deep passages seem to be the connective tissue between the huge rooms and shallower trunk passages in this system. As Brett came down the breakdown with the reel, the most obvious passage was to the right, which would hopefully go around the north side of the breakdown room and head east, which is the upstream gradient in this area. I went a few hundred feet and ended in what appeared to be a terminal room. As I scootered around the small room, I noticed a doorway on the right heading east. Just as I was getting my hopes up, I came into another perfectly round room, this time with no other exit. Brett tied off on the far side of the room and started surveying out. We had explored 179 m/ 587 ft of passage that we appropriately named Lost Hope.

On the way out, we checked the radio location ring at the top of the Sirius room. Sure enough, the LED had turned green, indicating that the surface team had successfully performed our deepest radio location to date at 104 m/ 340 ft. As such, we carried the ring back to the Mega-Y, where we dropped it for a second locate.

The Deepest Cave in Florida

The first weekend in February was our next opportunity for exploration. In the meantime, Kirill Egorov had captured some amazing photographs of Mount Doom and retrieved the radio locate ring. Andy and I made plans to check several known leads on the south side of the passage between the White Stripe and Sirius rooms. Andy was to check the leads while I kept an eye on the guideline, and if it went, he would bird-dog out front while I ran the reel. Andy checked what initially appeared to be a large alcove just before the Sirius room but found an ongoing passage on the left side and gave me the signal.

As I tied in the reel and followed him through the archway, it opened up and turned to the south, which was exactly where we wanted to go. This entire section of the cave is below 107 m/350 ft, and as I looked at my gauge, I realized we were exploring at 122 m/ 400 ft. Andy scouted ahead as the passage came up into a large breakdown room. The way ahead wasn’t apparent until we crested the breakdown and saw the going passage on the other side. After 207 m/680 ft of new passage, we came slightly up into the familiar looking White Stripe room. We immediately saw the line and tied into an existing tie-off at about 113 m/370 ft.

Now it was my turn to look around as Andy surveyed the new line. On the way back, I spotted a possible lead on the south side of the breakdown room and dropped down to check it out. In doing so, I not only found a likely going passage but hit 126 m/ 414 ft, setting a new depth record for Florida caves

On the way back, I spotted a possible lead on the south side of the breakdown room and dropped down to check it out. In doing so, I not only found a likely going passage but hit 126 m/ 414 ft, setting a new depth record for Florida caves.

Closer to where we started exploring, I also spotted another likely passage headed southeast. Normally a big loop would be disappointing, but this loop may open up one or more leads in the southeasterly direction, which is the upland gradient in this area.

A dry winter without much rain meant that the groundwater levels were dropping quickly. With only a few more weekends of diving available due to conditions and the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic shutting down the state parks, we made plans for two final exploration dives of the season. In mid-March, Brett and Andy checked the deep leads in the loop passage we had discovered on the previous dive. All the leads they checked turned out to be small without significant flow.

Racing the Pandemic

The next weekend, Matt and I headed in to check several leads, and the team rallied to pull nine safeties from the cave. Our first stop was a lead I had spotted at the start of the large loop that Andy Pitkin and I had put in several weeks prior. I initially looked into this lead while Andy was surveying and expected to see the large breakdown of the Sirius room, but to my surprise that’s not what I saw. I still thought this may just be a short loop, so I asked Matt to go to the base of the breakdown in the Sirius room, and I would quickly go in and look for his light.

As I went in through the window, I realized immediately that it was a medium-sized room with a passage headed off to the right or southeast. I looked around the room and didn’t see Matt’s light right away, but as I headed over to the left side, I saw the faint glow of his light beyond a duck-under in the Sirius room. I headed over closer and realized it was too small to pass, so I headed out. Matt obviously had the same idea, and we met in the middle. I gave him the signal that it went and signaled him to tie in to the existing line.

I bird-dogged as Matt followed with the reel, and we quickly entered the passage to the southeast of the room. I caught a quick glance at my depth as we descended past 128 m/420 ft. We dropped into what appeared to be a terminal room with conglomerates of rusty sand dollars on the ceiling. There were two low restrictions at 131 m/429 ft that opened up after a few feet, but there were no signs of flow, so Matt tied off as I started to survey out.

Our next stop was the Unknown. At the base of the Unknown is a room on the right that curves around and looks like it may go. I held on to the line while Matt checked this room again but as before, he found that it didn’t go. Matt and Andy had ended their exploration of the Unknown in the far east corner of the second room, the Attic. We checked that again without success. We also dropped down into the False Hope passage that Brett and I had explored on a previous dive. Unfortunately, the leads we had seen were low and had no signs of flow. Matt did spot one narrow lead with a bit of flow that could possibly skirt the northwest side of the breakdown.

Luckily, we had one more lead to check that I had spotted on the way in at the bottom of Mount Doom. Until recently, Mount Doom was the deepest part of the cave at 124 m/407 ft. The lead was on the far side of a saddle, which made it hard to see unless you were on the far south wall looking straight down. As I came through the restriction up into Mount Doom, I went left over the saddle rather than right toward the exit. I paused long enough to flash Matt, and he quickly headed back my way as I dropped straight down in the crease toward the white sand ripples at the bottom. The duck-under was large enough to pass, and I could see a room on the other side. I went through knowing that the glow of Matt’s light would provide a reference to exit. The room was wide and had at least one going passage to the south. We had no time to explore it further, so it will have to wait until next season.

As I write this season recap at the beginning of summer, the groundwater levels are still dropping due to the unseasonably dry winter. Hopefully, the summer rains will recharge the system quickly so we can get back in and explore the newly discovered passage at the bottom of Mount Doom. Until then, KUR divers will continue to focus on other projects.

Dive Deeper

Check out Karst Underwater Research

Alert Diver: “Where Mermaids Fear to Tread”

Charlie Roberson is an attorney who lives and works in Gainesville, Florida. He is the founder of FATHOM Dive Systems, LLC, a manufacturing company that focuses on life-support equipment for underwater exploration.

Charlie learned to dive in 1991 while serving in the U.S. Navy. He then spent the next two years diving the wrecks and deep walls of the Western Pacific. After returning to the states, he moved to Gainesville to attend the University of Florida and take up cave diving. Years later, he is still cave diving and currently holds the world record for penetration in an underwater cave at 8,208 m/26,930 ft.

Charlie is a director of Karst Underwater Research (KUR) and has participated in numerous KUR exploration and survey projects. Most recently, he traveled to Mexico for expedition caving projects in the Peña Colorada and Río Uluapan. Charlie also serves as the preserve manager for the National Speleological Society’s Mill Creek Sink Preserve and as the diving coordinator for Florida Speleological Researchers’ Diepolder cave system.