Community

Diving Into “Ghost Ships of the Baltic Sea”

Veteran magazine editor/designer and wreck diver Jesper Kjøller, who grew up on the Baltic, examines what is arguably the most extravagant and uncompromising wreck photo book ever produced.

by Jesper Kjøller

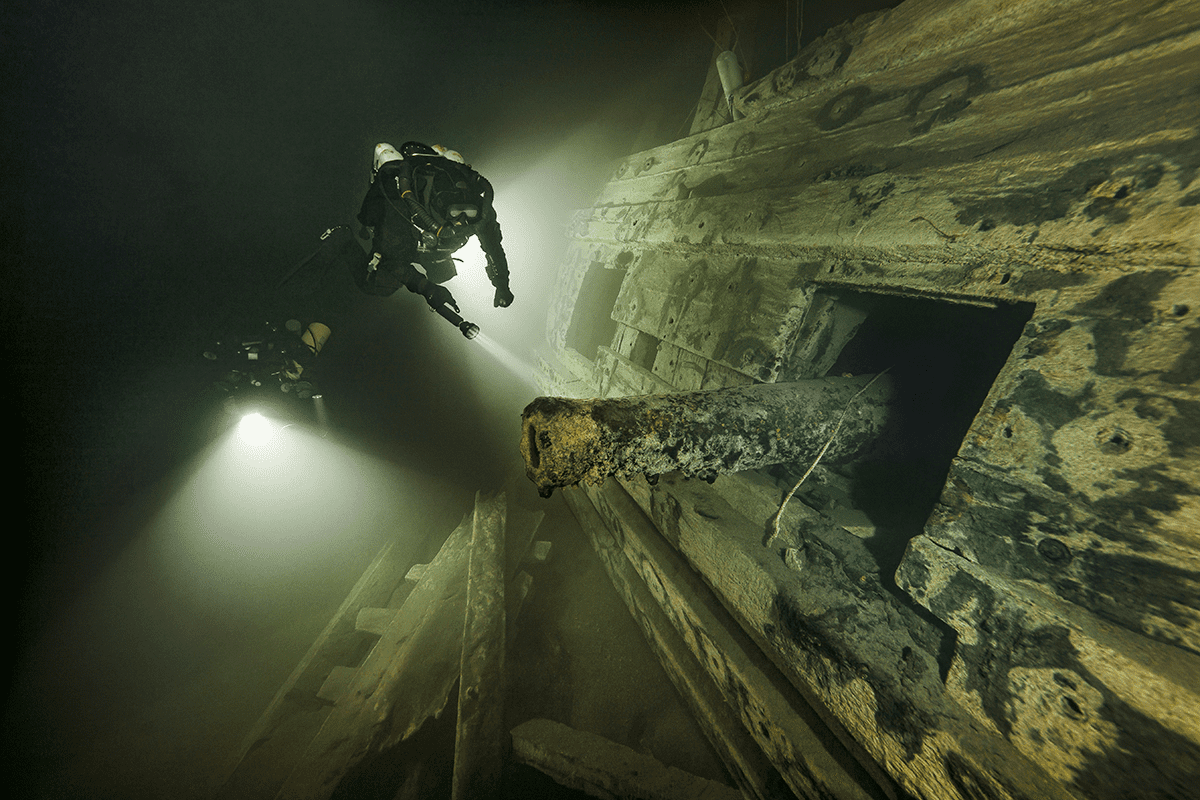

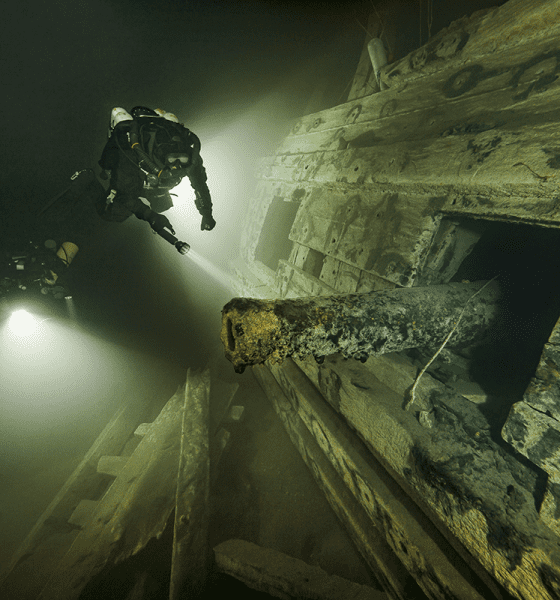

Header image by Jonas Dahm: Diver assessing the guns from Swedish Navy warship Svärdet

If you’re a sucker for well-preserved wrecks with historical significance, Ghost Ships of the Baltic Sea is a must. It is an amazing photo book featuring some of the most spectacular wreck photography ever published in an extravagant and uncompromising design.

As a kid in Denmark, I spent time every July in my grandparent’s summer house on the shores of the Baltic Sea. I loved swimming, fishing, sailing, and snorkeling in the brackish ocean. The distinctive feel and smell of the Baltic water remain an integral part of my childhood memories. The same sentiment emanates from every page of Ghost Ships of the Baltic.

But what makes the Baltic so special, and why is it a wreck explorer’s dream hunting ground?

The Baltic Sea is the world’s largest inland brackish sea with a salinity considerably lower than typical ocean water. It is diluted by freshwater runoff from the surrounding countries balanced against evaporation from its relatively shallow basin.

The sea generally has a salinity between 0.3% to 0.9%, which is almost freshwater. The low salinity supports sparse marine life, and the absence of ships worm and marine growth results in exceptionally well-preserved wooden wrecks. By comparison, wrecks in tropical waters are quickly covered by corals, and the structures eventually crumble under the weight of the growth. In the Baltic, the wrecks often look like they just went down a few hours ago, even if they are several hundred years old. So, from an ecological standpoint, the Baltic is unique.

But the cultural and historical significance of the Baltic also contributes to its uniqueness.

Truk Lagoon and Scapa Flow are often heralded as the wreck diver’s nirvana. Exciting as these destinations are, they are dwarfed by the Baltic Sea, which is believed to contain more than 100,000 shipwrecks: the result of a rich (and often violent) 1,000-year history. The seabed of the Baltic feature Viking ships, 15th century warships, WWI- and WWII-era battleships and submarines, and modern vessels such as ferries and cargo ships.

A Labour of Artistry and Love

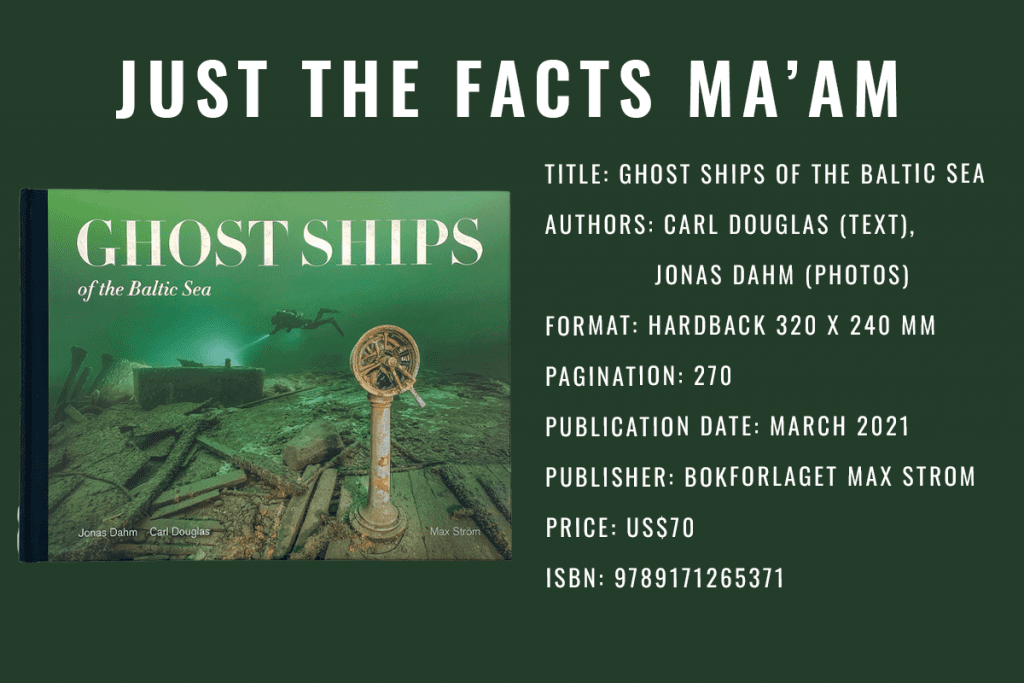

After more than two decades and some 3000 dives, Deep Sea Productions, led by Swedish business entrepreneur Carl Douglas, has located around 400 wrecks in the Baltic. Throughout their explorations, Carl and his team have collected stories and images from the wrecks, publishing their results in Ghost Ships of the Baltic for readers to enjoy. The book, which was 14 years in the making, showcases a collection of the most exciting and prominent wreck discoveries made over the last 25 years.

It is nice to experience something as extravagant and archaic as a large, thick, and heavy tome in this day and age when we mostly consume content on screens, and printed books and magazines sometimes appear to be a thing of the past. However, this is the only format that would do justice to these amazing and unique images.

Douglas’s texts are brief, to the point, and geared toward a general audience without specialized knowledge about wrecks or diving. His passion for wreck exploration and history is evident, and he is a storyteller at heart. By nature of its sheer size and weight, this is not a book you read cover to cover—it would be a challenge to read in bed, for instance. The narratives are companions to the images and serve as commentary, not as running prose. This works quite well. Readers do not have to read in sequence; they can jump freely around as specific images catch their attention and pique their curiosity.

Some of the chapters outline the Baltic history, while others dive deeper into specific wrecks and the stories of how they sank. But my favorite chapters explore a cross-section of subjects such as cargo, navigational equipment, ornaments, and figureheads.

While the explanatory text is focused and concise, the real stars are the images. No one browsing this book will be left untouched by seeing these wrecks and the abundance of photographic details. Intact wheelhouses with compasses, machine telegraphs and steering pinnacles, spiral staircases, cabins with bunks, signage, galleys with cutlery and tableware, captain’s staterooms, card rooms, and even musical instruments and human remains all tell profound human stories. The “Ghost Ship” expression in the title has never been less of a cliché.

The images that most significantly resonate with me are exterior shots showing larger parts of the wreck, often employing techniques that display the wrecks in a way that can’t be captured with the naked eye.

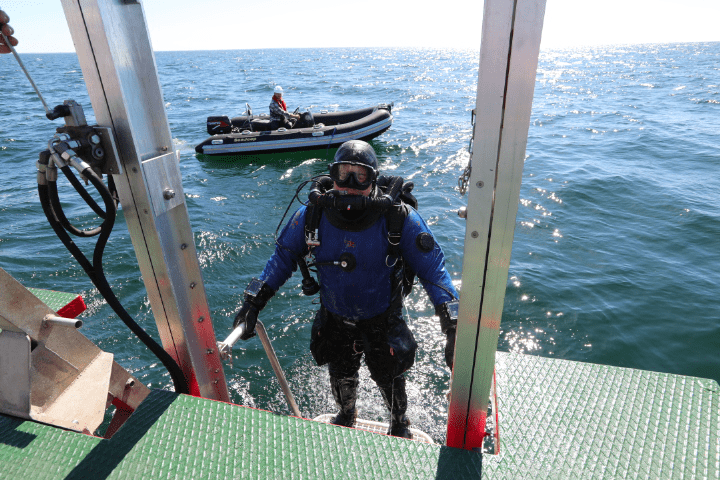

The book is co-authored by the retired firefighter and wreck photographer extraordinaire Jonas Dahm. He has developed unique methods to capture the essence of the Baltic wrecks. Often, they rest in almost complete darkness even if the water is clear. The low solar angle at northern latitudes and the layers of algae in shallow water dims most of the light at greater depths. Even the shallower wrecks rest in an eternal twilight, so special techniques were employed to capture the wrecks in all their splendour.

Cunning combinations of slave strobes, off-board video lights, high iso-values, and slow shutter speeds allowed Dahm to reveal the wrecks with depth and details never seen before. This would have been impossible with traditional onboard flash photography that mainly illuminates the foreground and often renders the background more or less completely dark.

These imaging techniques require significant preparation, teamwork, and patience, but the results speak for themselves. The images are simply stunning; however, they are actually deceiving in a way—you may be disappointed after diving these wrecks in person, as the images capture a magic that isn’t as tangible in reality. But, then again, all photography is manipulating reality. And these images almost have a textural property—they seem to leap off the pages, and the printing quality is sublime.

Black is Back?

The widescreen format of the book really gives justice to the images, but I do not agree with the choice to cover the portion of the pages beyond the boundary of the photos in black. I appreciate the intention to provide the images with maximum attention and to remove all interference; there are no captions, no names or explanations, not even a page number on the image spreads.

This is a bold choice in the presentation of the material, and it carries a certain punch. But a massive amount of real estate is taken up by black, which feels a bit wasteful. I would probably have made a different layout choice and used some of all that black space for captions. (Ed. note—the author is a veteran magazine editor and graphic designer.) I would have loved a section explaining the imaging techniques used. A few behind-the-scenes shots showing the setup and the support divers handling video lights and tripods would have satisfied the curiosity of nerdier readers.

The author’s intentions are clearly to give the images as much space and emphasis as possible and remove all unnecessary clutter to highlight the pictures as much as possible. If that is the goal, they have clearly succeeded. I respect that choice, even if it is carried out almost to the extreme.

If it is not already on your bucket list to explore the Baltic Sea, I’m sure this book will compel you to move a trip there to the top of your list. Meanwhile, you can enjoy exploring Ghost Ships of the Baltic Sea in the comfort of your armchair.

Dive Deeper:

You can purchase Ghost Ships here! You can also find it on Amazon.com!

Originally a professional musician, Jesper fell in love with diving almost 30 years ago. He made a career change and became instructor in 1994 and PADI Course Director in 1999 when he was offered the editor chair of the Scandinavian Diving Magazine DYK. Jesper became a GUE instructor in 2011, and in 2015 he moved to Dubai to apply his skills in underwater storytelling and imagery as Marketing Manager of Deep Dive Dubai. From Dubai he travels the world to teach and report for international dive magazines and to participate in dive projects like the yearly Mars field studies in the Baltic Sea or deep wreck explorations in Egypt. In 2021 he began as Editor-in-Chief of Quest, the GUE Member Journal.