Community

Fact or Fiction? Part 2: Interview with World Record Holder Ahmed Gabr

by Michael Menduno

See Part 1: Fact or Fiction? Revisiting Guinness World Record Deepest Scuba Dive

See Guinness World Records’ response to the allegations at the bottom of the story.

The day before this issue of InDepth was to go LIVE with Gabr’s world record story—I had reached out to him to comment but he declined—I received an email from Gabr. He apologized for any previous confusion and told me that he had checked my credentials and legitimacy and was now willing to grant me an interview. An hour later, we were speaking on FaceTime. Gabr was animated and very talkative. He would frequently go off on tangents and I had to keep bringing him back to my questions. At first, he seemed a bit nervous, but he started to relax more as the conversation went on.

After we briefly talked about his military background—note that he made the dive while still a colonel in the Egyptian army—I began by asking Gabr why he thought these allegations were surfacing now, six years after he conducted his world record dive. He said he believed it was because a documentary of his dive had been completed, and his detractors wanted to get back at him. “Their agenda is to discredit me and the movie,” he said. I asked him if he knew who Scuba Sam was, and he told me that he was a former disgruntled member of his team that had fled Egypt under legal suspicion and wanted to get back at him.

Gabr verified that the head cam video included in Scuba Sam’s email was accurate. I asked him why he hadn’t carried a camera and filmed the dive to begin with. He explained at the time he had an 8-year old child and a pregnant wife, and he said it would have been a huge stressor for him to know that they might see the video if he had died. For that reason, he hadn’t videoed his training dives either.

What About The Depth Timer?

I asked Gabr about Scuba Sam’s first allegation, whether his Scubapro 330 m Depth Timer with blacked out corners—that only showed his Maximum Operating Depth—was metric or imperial. He answered by first saying that computers were not required as part of the validation and launched into a detailed explanation of Guinness’s measurement methodology.

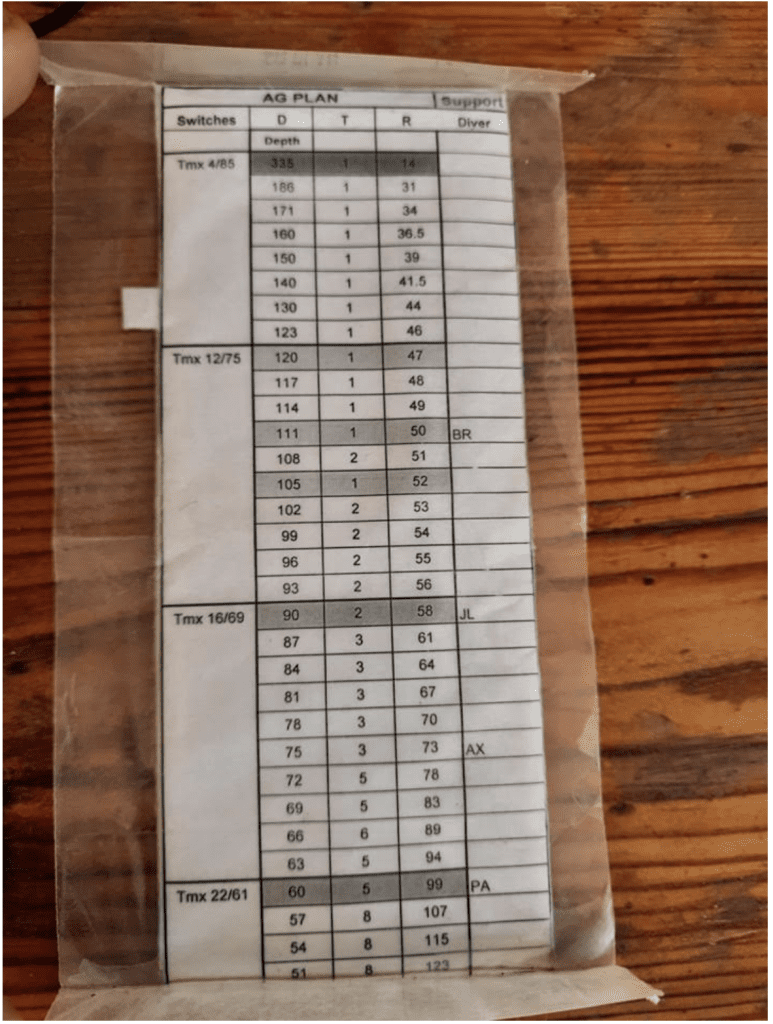

Guinness’s procedure for validating the dive was twofold. First, Gabr had to retrieve one of the unique, signed, and wrapped depth tags from the certified descent line. More on procedure surrounding the tags later. In addition, Gabr’s deep support diver, who met him at 90 m/295 ft, instead of 110 m/361 ft, as planned, was supposed to video him giving a special hand sign indication “3-5-0,” which was requested by the Guinness adjudicator shortly before the dive. In addition, he was to display the retrieved tag, which was the 335 (335 m/1094 ft) tag as shown in the video. He said that only the adjudicator, deep support diver, and Gabr knew the sign. Computers were not required. However, Gabr told me that he was so excited that he held out his Depth Timer (DT) which showed a max depth of 330. The question is whether it was feet or meters.

I asked him why he had blackened out the three corners of the Depth Timer so that only the max depth was showing. Note that only the last digit of the current depth reading, and part of the preceding digit, in the upper left-hand corner is showing. He explained that he did that before his last training dive because he was worried that breathing helium beyond 300 meters would give him hallucinations, so he wanted to keep his brain focused by having a single number. Is max depth the best number to have if you could only have one? Wouldn’t it be better to have current depth if you were hundreds of meters from the surface? Gabr’s account contradicts the explanation that two of his team members independently gave me. They reported that Gabr told them it was to insure the integrity of the device under pressure as per the manufacturer.

Gabr explained that he made the dive with four measuring devices: two computers, the Depth Timer, and a Swiss military watch which was rated to extreme depth. He told me that he clipped one of the computers on the line at 90 m/295 ft on his way to depth, as he was worried that it would fail and he wanted it to keep track of his overall dive time compared to his runtime table. He later retrieved the computer which is shown in his hand with double enders in the video. Gabr then said that the main computer died (went blank) at 290m/796 ft during his descent.

OMG! How did he monitor his depth with no working computer and a depth timer only showing MOD? Gabr explained that he used the rope as his “depth tool,” and his watch to keep the time?!? Wow. Can you imagine? What if you got blown off the line? The rope was NOT marked in 3 m/10 ft increments. Rather, according to the engineering report, it was marked in 5-meter increments from 320-350m, and 50-meter increments from 300-150 m, then 10m increments from 120-100 m, and the 3m increments from 96-90 m, where he met his first safety diver. In other words, it would be very difficult to follow as a depth guide, particularly if he were suffering confusion. Gabr reported to me that he was mentally confused and feeling drained at depth.

Note also that Gabr’s first three planned 1-min deep stops (186 m, 171 m, 150 m) were not marked on the rope, nor his stops at 140, 130, 123 (see the partial runtime deco table shown in Part 1). On the video, Gabr gave his first safety diver the OK upon meeting him at 90 m and later reported that the dive went according to plan. No mention of computer problems or the lack of a depth-keeping device at depth.

Again, I asked him about the Depth Timer, whether it was the imperial (feet) version as alleged, or the metric version. Specifically, if it were the metric unit, why wasn’t the decimal showing before the last digit of current depth? [See the analysis in Part 1] Note that the Scubapro metric unit shows the current depth shallower than 100 m in three digits XX.X, to the tenth of a meter. Gabr said that the device “wasn’t in feet.”

What happened, he explained, was that the depth timer began to flood on ascent, and as a result, the decimal point indicating that it was a metric unit and the temp reading had disappeared by the time he reached 90 m/295 ft. He said that eventually the face of the depth timer went blank. Again, Gabr pressed the point, “Why do I need to fake something that is not even required [for the record]?”

One source told me that Gabr had been wearing his metric depth timer on his previous training dives with a standard strap mounting. However, the depth timer in the video has bungee cords. Was the metric device swapped out for an imperial version for this dive?

What About the Gas?

I asked Gabr about arriving at his 90 m/295 ft stop, where he met his deep safety diver, roughly eight-minutes (21 meters shallower) earlier than the plan. He explained that it wasn’t an issue and was within his calculated safety limit. He said that he had reached the 335 m/1099 ft depth tag between 12-14 minutes, and in the absence of a working depth monitor, he ended up making his first stop from depth at 150 m/492 ft using the rope markings. The plan called for slowing his ascent rates as he ascended through various depth zones.

I next asked him about the video which shows him breathing his back gas (trimix 4/85) as he is met by his safety diver at approximately 90 m: “Why were you breathing your bottom mix?” Gabr answered immediately, “I ran out of deco gas.” He then launched into an explanation about Isobaric Counter Diffusion (ICD), and why it wasn’t a big concern for him to switch back to his back gas because the differences in nitrogen were minor. But what about the oxygen?!?

Note also, that none of the tanks had SPGs. I asked him about this. “It’s a weak point for failure,” he explained. However team members told me that all cylinders were triple checked, analyzed, and marked for proper contents prior to the dive.

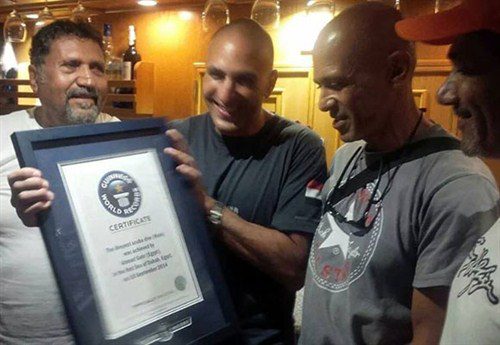

In the video, the safety diver descends to Gabr, asks in sign, Are you Ok? Gabr, who appears very relaxed, responds with an OK sign. No mention of an out-of-gas issue. Gabr then displays his retrieved 335 tag, shows his Depth Timer reading 330, and makes the sign requested by the Guinness adjudicator 3-5-0. “The first thing I wanted to do was secure the record, and do the whole video process,” Gabr explained. He next secured the tag to his support diver to prepare it for its trip topside. “My nightmare was that my deep support would lose the tag so I zip-tied it to his D-ring.”

After the Guinness protocol was accomplished, the safety diver switched out Gabr’s empty stages and passed him his stage bottle with trimix 12/75 deco gas, that was supposed to be breathed from 120 m up to 90 m. Gabr then went back on his deco gas. The support diver also sent up a status slate to the surface indicating Gabr was OK. The 90 m safety diver met them soon after, and facilitated Gabr’s gas switch to trimix 16/69.

There were several things that were a bit inexplicable. First, if you had just completed a 330+ meter diver, lost a computer, and then ran out of deco gas prior to your 90 m stop while you were facing another 14-hours of decompression, would you give your safety diver, who was carrying back-up deco gas the OK sign? Again, according to Guinness and other news reports, Gabr said that the dive went as planned. Second, were Gabr’s priorities. Wouldn’t you switch to your deco gas and then do the record protocol?

Finally, most troubling, Gabr had four 12L cylinders of 12/75: three staged on the line and one in a carried stage bottle. According to the plan, Gabr was to breathe 12/75 from 120 m to 90 m, for a period of 15 min at an average depth of 110 m or 12 atm. You do the math. For example, with a high 20L surface consumption rate for example, he should have burned through 20L/min x 12 ATM x 15 min=3600 liters. That’s roughly 1.5 12L cylinders, not four. Was he in that depth range longer? Gabr acknowledged that he had burned through lots of gas between those depths and was crazily coughing and had some chest pain. He thinks he had mild pulmonary edema.

Lines, Tags and Fitness

The fourth allegation concerns the angle of the descent line. The video, 50-minutes into the dive, shows the line at what is estimated to be 25º angle, which performing a trigonometric analysis, would mean that the 335m tag would be at approximately 303 m/989 ft short of the record. Gabr explained to me that the Guinness adjudicator and the calibration engineer who was on board measured the angle of the descent line at 15 minutes into the dive. Accordingly they subtracted 2.65 meters to arrive at the record of 332.35 m/1094 ft and 4.5 inches.

The fifth allegation is that there was a broken chain of custody with the tags, meaning that they could have been altered or replaced prior to the dive. Gabr disputed the claims. Though he wasn’t present for all of it, he said that the tags were under the control of the adjudicator the whole time, who even had his own locks to secure the tagged line the night before the dive. That is in Guinness’ bailiwick to determine. Gabr said that the adjudicator watched him dress and searched him prior to the dive. Eye witnesses reported that Gabr and his lead support diver were not searched thoroughly for tags before entering the water, and that the diver who escorted Gabr to depth was not searched.

Finally, I asked Gabr about his reported high energy level following the dive, which contrasted sharply with Gomes’ experience who had to be helped to walk (See Part 1). Gabr, who is reportedly very fit, explained that, unlike Gomes, he removed his quads at 21 m/70 ft and so only wore them for 4.5 hours. Gabr said that he also hydrated and ate every hour during his shallower deco stops, which he asserted Gomes’ did not. He also pointed out that at 41-years old at the time of the dive, he was 12-years younger than Gomes when he set his record. Ouch! I later checked with Gomes’ who said that he also hydrated and ate. As discussed in Part 1, Gomes insists the quads were not an issue for him. We ended the post-dive discussion with Gabr pointing out that its difficult to compare one person to another.

What now?

I asked Gabr what he intended to do. To my surprise he launched into a story about a sustainability project he was involved in with the first Egyptian to climb Mt. Everest. He then told me about a shipwreck exploration project in the Mediterranean in late September that he planned to do a pilot film about. I finally interrupted him. “But what about the allegations?”

“I have no idea,” he said. “What do you think?” “It’s up to Guinness,” I offered. “No, Guinness is done with it. It’s over,” he said. I asked Gabr if he had been in touch with or heard from Guinness or his project leader. He said he hadn’t, adding that, “They have a bullet-proof system.” He went on. “I am confident in what I did. But it bothers me that my reputation has been targeted. Why do I have to justify myself? I am confident, but I’m being hurt,” he said.

He went on. “Why are they doing this now, after six years,” he asked rhetorically. “Usually people try to discredit a record at the time it is made. But why six years later?”

“Do you think it’s because of the documentary film?” I asked. “I’m sure about that,” Gabr replied. “It’s the same person who was with the team. He was trying to sell helium illegally in my name and got me into trouble. He wants to discredit my whole record and the movie,” he said.

I asked if Netflix was going to release the documentary, which several people had told me about. Gabr said, no, that the documentary, which had investors, had not been sold yet. “Netflix didn’t buy it?” I asked. “No,” he said. I asked him several times if he had a financial stake in the film but did not get a clear answer, though he acknowledged he was under contract.

Gabr then said about his anonymous accusers. “They are not searching for the truth. They only mention half the truth. There was no peer review from professionals. My record would be discredited if I had relied on one of the computers. For sure. But that was not the measurement methodology.”

I asked Gabr if he would be willing to have a peer group review all the information and possibly clear him. Gabr said that he was open to anything. He said that he has been using the same video in his talks as presented in the emails and is always willing to sit and discuss things at every dive show he attends. “I don’t mind talking about my dive,” he said.

Conclusions?

There is obviously a lot of information to unpack, and numerous additional details, as well as information protected by confidentiality that I have omitted here. It’s clear to me that I am not in a position to render a judgement, nor is it my job. My job has been to ask questions, lay out what appear to be the facts as best and fairly as I can and point out inconsistencies as I see them.

As I said before in Part 1, it’s up to Guinness to decide if they want to investigate the allegations or not, and on that basis to determine if Gabr completed a record dive or not. However, given the widespread distribution of allegations about the record, and what seem like surprising discrepancies, it’s likely that his record will remain under a shadow until the full truth is known, whether by Guinness or perhaps, as Gabr suggests, through a peer review by professionals.

SEP 1, 2023—Editor’s Note: Guinness World Records finally reviewed and responded to the allegations re: Gabr reported record dive in early 2021, stating there was “no conclusive evidence establishing foul play.” See: Guinness World Records concludes review into deepest scuba dive (male) record. The trouble is that their investigation did not address specific allegations, nor did they interview members of Gabr’s support team who raised concerns. Guinness World Records did not respond to InDEPTH’s queries regarding their investigation. As a result, questions about Gabr’s dive remained unanswered.

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s editor-in-chief and an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving (1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012, and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018. In addition to his responsibilities at InDepth, Menduno is a contributing editor for DAN Europe’s Alert Diver magazine and X-Ray Magazine, a staff writer for DeeperBlue.com, and is on the board of the Historical Diving Society (USA).