Community

Fact or Fiction? Revisiting Guinness World Record Deepest Scuba Dive

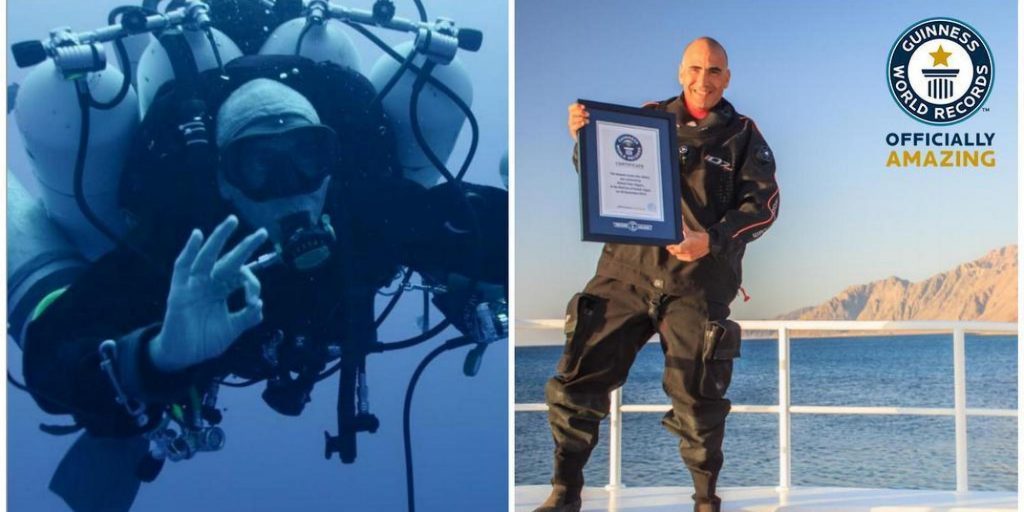

Newly released information calls into question the validity of former Egyptian Army Colonel and instructor trainer Ahmed Gabr’s 2014 world record scuba dive to 332 m/1,090 ft in the Red Sea. InDEPTH editor-in-chief Michael Menduno reports on what we’ve learned, why this information is coming out now, and what it all may mean.

by Michael Menduno. Header image courtesy of DeeperBlue.com.

See Fact or Fiction Part 2: Interview with World Record Holder Ahmed Gabr

See Guinness World Records’ response to the allegations at the bottom of the story.

Diving insiders were dismayed and saddened last month as an anonymous group of individuals using the moniker “Scuba Sam,” published a series of emails with the here-to-fore private details of the 47-year old, former Egyptian Army Colonel and tech instructor trainer Ahmed Gabr’s Guinness world record deepest scuba dive to 332 m/1,090 ft on September 18, 2014, in the Red Sea off the coast of Dahab, Egypt. He reportedly broke South African cave explorer Nuno Gomes’ previous world record of 318 m/1,044 ft set in Dahab in 2005. French cave explorer Pascal Bernabé also reportedly made a record deep scuba dive to 330 m/1078ft in Propriano, Corsica in 2005, several weeks after Gomes’ record dive, but the dive was not recognized by Guinness.

The emails, which were organized into six installments and sent to numerous high-profile technical divers including Gomes, as well as dive media outlets before being posted on Facebook by “Scuba Sam in August, called into question the validity of Gabr’s record, specifically whether he reached a record depth at all. The emails were also sent to Guinness World Records. A representative confirmed to me that they were being reviewed by the company’s Record Management Team.

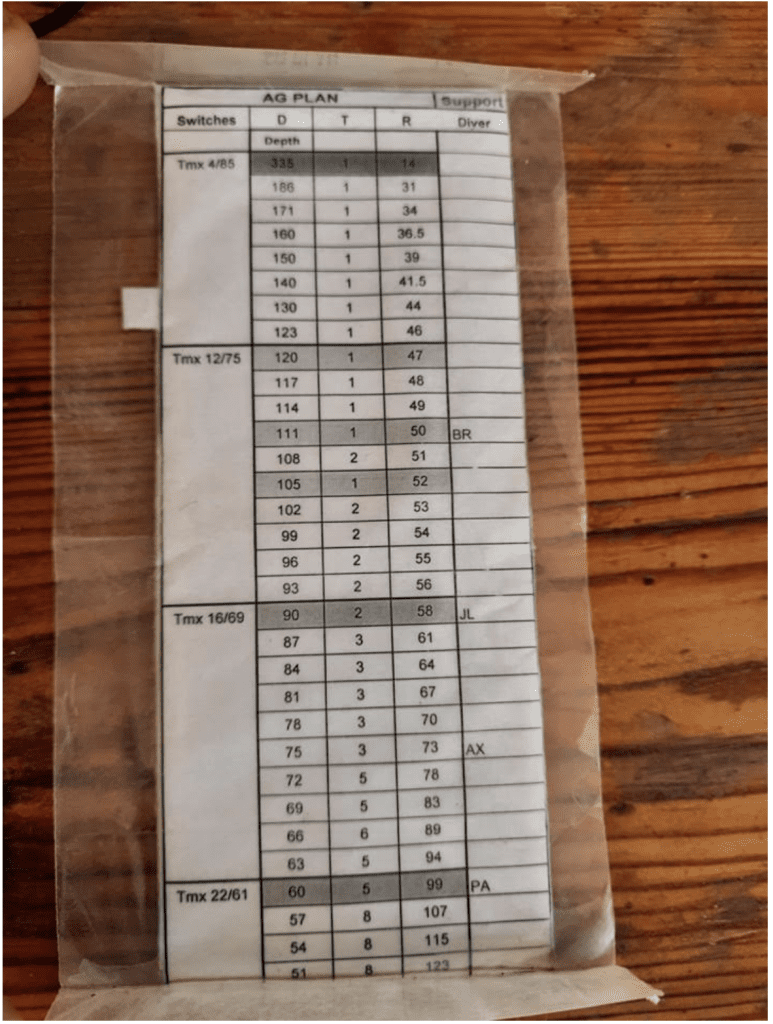

Each of the emails offered a detailed analysis of a critical aspect of Gabr’s dive based on information that had been kept largely private until now. This information included a continuous headcam video taken by Gabr’s lead support diver, part of the actual “runtime” dive plan showing Gabr’s initial planned gas switches and decompression stops, and a detailed report of the chain of custody of the special Guinness depth tags that were to be used to validate the record.

Taken as a whole, the analyses highlighted a number of substantive discrepancies in Gabr’s reported depth record claim and raised questions about Guinness’ quality control, and perhaps about deep diving records themselves. It will be up to Guinness, of course, to determine whether the allegations are valid, and if so, whether Gabr will be allowed to retain his record.

The history of diving can be characterized as a search for greater depth and increased bottom time, so it shouldn’t be surprising that there are deep diving records. The fact is they represent a kind of a conundrum in technical diving culture. On the one hand, for the individual, deep record scuba diving is extremely dangerous, akin to physiological Russian roulette, and arguably lacks meaningful purpose other than bragging and or promotional rights. On the other hand, as a community, we are driven by our genetic disposition to explore and determine exactly where the limits are, how deep we can safely go. The question is how do we, as a community, strike a balance between the two.

It’s worth noting that compared to extreme compressed gas diving, the balance point is considerably different for internationally-sanctioned freediving depth competitions, which have a strong safety record, and are primarily athletic endeavors.

Historically, in the case of deep world record scuba dives, numerous divers have lost their lives trying to beat a prior record. In Gabr’s case, there have been at least two known unsuccessful attempts to beat his record, both of which resulted in fatalities. As a result, many tech divers are unsupportive of these types of dives and think they should be discontinued. The possibility that a world record dive could be faked casts further doubt on their veracity. The possibility that someone might actually fake one, well….here is what we know.

The Analysis

Rather than simply contesting Gabr’s record, Scuba Sam’s episodic analyses raised pointed questions about his dive, based on the evidence used to validate the record, which had not been previously made public. According to Scuba Sam, Gabr was required to produce two pieces of evidence to validate his dive. First, he had to retrieve one of a number of unique, signed depth tags that were attached to the descent line under the supervision of the Guinness adjudicator, in five-meter increments (320, 325, 330, 335 etc.) beginning just beyond the depth of Gomes’ record.

Second, the first deep support diver would video meeting Gabr at depth during his ascent. In the video, Gabr would show the retrieved tag, along with the screen of his dive computer showing his maximum depth, which presumably would correlate with the depth on the tag. The support diver would then ferry the tag, which would be zip-tied to his shoulder D-ring, to the Guinness representative, who then inspected it for authenticity and viewed the video to confirm the maximum depth, and then granted Gabr the record. It should be noted that, according to sources, the Guinness adjudicator was not a diver.

Based on careful examination of the evidence, as well as their intimate knowledge of the dive, the Scuba Sam collective, which likely includes members of Gabr’s record dive team (or at least has been in touch with them), uncovered five discrepancies that raise serious questions about the legitimacy of Gabr’s record.

- Gabr’s ScubaPro Digital 330 m Depth Timer, which according to sources was covered with neoprene glue to protect the crystal, obscuring all the readings except “maximum depth,” was identified to be the Imperial and not the Metric version of the device. As a result, the maximum depth reading of 330 was in feet not meters. The Depth Timer and another computer did not survive the dive. A third surviving computer was clipped at 90m by plan and never went to depth.

- Though he reported that his dive went according to plan, Gabr was 21 m/70 ft shallower, and eight minutes ahead of his runtime schedule, when he met his first support diver at 90 m/294 ft approximately 50 minutes into the dive. Shortening or altering the approximate 15-hour-long decompression schedule could significantly increase the risk of a serious decompression injury. Dive team members (see below) told me that it was highly unusual for the schedule to vary by more than one to two minutes during training dives. “Even a one-minute difference on a 200-meter plus dive was a big deal,” one team member said.

- In the video, Gabr is seen calmly breathing the wrong gas—his trimix 4/85 (4% O2, 85% He, 11% N2) back gas at 90m/294 ft, instead of from his trimix 12/75 stage bottle, which he was supposed to switch to at 120 m/392 ft. The stage appears unused with the regulator still in place, however the image is somewhat obscured. Improper or missed gas switches on a dive of this magnitude could cause serious injury or death.

- A trigonometric analysis of the angle of the descent line based on line markings—divers reported a fierce current—would likely put Gabr’s 335-meter tag at about 303 m/989 ft, which would be shy of the record.

- Reportedly, there were at least three breaks in the chain of custody of the depth tags following the arrival of the Guinness adjudicator, and an arguably less-than-transparent process, meaning that the official tags could have been altered and or replaced prior to the record dive. In addition, eye witnesses reported that Gabr and his lead support diver were not searched thoroughly for tags before entering the water. As one witness put it, “Gabr probably could have smuggled a firearm past.” The descent line was pulled up the day after Gabr’s record dive, but the event was not recorded or documented.

What About Gabr’s Dive Team?

When I read Scuba Sam’s first and second emails, my first instinct was to want to validate that the video and dive plan information was authentic. I was also skeptical as to why this information was coming out now, roughly six years after Gabr’s dive. Fortunately, an industry friend put me in touch with a member of Gabr’s dive team, who agreed to speak with me on the condition of anonymity.

The diver then referred me to another member of the team, who referred me to another. All together I interviewed five team members, who validated the authenticity of the video and the plan, along with a local tech operator. Note that the original dive team consisted of 22 members including 12 support divers, who spent nine months working with Gabr to train for his record attempt, which included 22 training dives, and consumed more than 500,000 liters of helium, and more than 250,000 liters of oxygen. The gas was donated by sponsors.

After speaking among themselves, the team members I interviewed decided that as a group they wanted to remain anonymous for this article. Three of the individuals told me that they were afraid of possible retaliation from Gabr and feared for their well-being and their livelihoods. According to them, one support diver who was involved in retrieving the descent line the day after the dive, was reportedly threatened, subjected to a campaign to discredit him, forced to give up his ownership in the local dive shop and ended up fleeing Egypt for his life, several months after the incident.

All five of the team members that I spoke to were angry, distraught, and felt betrayed. “Each of us had questions at the time, but there were plausible answers. When I put it all together now, I feel stupid,” one said. Another said, “I just want the truth to come out. I’m fuming!” And another, “I haven’t heard any good answers. I don’t want to help someone who has cheated.”

Several team members told me that when someone confronted Gabr about his breathing back gas after seeing the video, he reportedly responded by saying he had run out of (deco) gas, contradicting his earlier statements that the dive had gone as planned. “There are just so many holes,” a support diver noted.

Small Discrepancies

According to team members, there were numerous small discrepancies leading up to the dive, each with plausible answers. At the time, no one had put them all together. Why did Gabr put neoprene cement on the corners of his ScubaPro Depth Timer obscuring almost all of the read-outs except for maximum depth? Ans: It was recommended by the manufacturer to protect the integrity of the crystal face. Why would Gabr plan to clip off one of his dive computers at 90m and not take it to the bottom? Ans: To make sure he had a working computer on ascent. Why were there no submersible pressure gauges (SPGs) on the tanks? Ans: Fewer points of failure. Why wasn’t Gabr willing to carry a camera to document the dive? Ans: He didn’t want his children to see the video on the Internet, if he were to die.” All plausible answers taken by themselves, but taken as a whole potentially represent a pattern of non-transparency.

In addition, team members noted that Gabr seemingly had a surprising amount of energy after surfacing from his 15-hour dive, which finished at about 12:30 am. After offering a military salute, he was chatting and shaking everyone’s hands and had to be told to sit down. He even had to be dissuaded from running later in the morning.

In contrast, Gomes was so exhausted following his 12-hour world record dive, he had to be helped to walk off the boat, was placed on a saline drip, and was wheeled to the car with a diving doc in attendance and was driven to his hotel. There he was given a medical, put on precautionary oxygen and went to sleep. He rested for several days but he said that it took him a couple of weeks before he was back to normal. John Bennett, another prior 300m/979 ft reportedly had a similar experience.

Some speculated that the difference was due the fact that Gabr’s team removed his quads (four back mounted cylinders) and switched him to a sidemount rig at his 21 m/70 ft stop, while Gomes stayed in his quads the entire dive. However, Gomes, who has been diving quads since 1996 and has hundreds of in-water hours on them, is insistent that wearing quads had nothing to do with his condition. “I can tell you with 100 percent certainty that having the quads on by back throughout the dive made absolutely no difference to my condition and how I felt afterwards,” Gomes wrote to me.

Why weren’t any of the discrepancies highlighted in the video noticed on the day of the dive? Those present reported that it was a stressful operation. “The day was insane. Chaos. There were people, press and police. There was no time to think or compare notes,” one team member recalled. Conditions were also stressful, with a ripping current. The support boat reportedly even ran out of food. “It was the most stressful day of my life,” a support diver told me. Another explained that he was so task loaded, all he could do to focus on his job. Gabr’s dive concluded about 12:30 am. By 1:30 am, the boat was back at the jetty. Gabr was then awarded his Guinness world record certificate.

So why is all of this coming out now, six years after the dive?

Blame it on the COVID-19. After much of the northern hemisphere went into lockdown earlier in the year, one team member reportedly decided to use the time to write a book about the world record dive experience, and got in touch with others to discuss their experiences, to compare notes, and then he began reviewing the data. No one had reviewed the video. “It was a holy shit moment. We were seeing the video with fresh eyes, not what we had wanted to see,” a team member reported.

What Now?

After seeing the first four emails and interviewing team members, I reached out to Gabr to see if he would be willing to speak with me on the record. He responded quickly and said that he would be willing to talk but asked if we could wait until the final installment of Scuba Sam’s emails had been published. I contacted him again after the final email episode was released and the various analyses posted on Facebook. Gabr said he would be happy to do the interview in the next few days and gave me some possible times. He asked if I would email him the list of questions that I planned to ask. I sent him my questions and waited to hear back.

Gabr wrote back to me the day before we were tentatively scheduled to talk. He thanked me for my interest but explained that he wouldn’t be able to do the interview. “Not because I don’t want to,” he wrote, “but because all my media interactions have to be approved first by my legal team and they advised against doing the interview for the time being.” [Author’s note: Gabr contacted me and agreed to do an interview just as this story, and issue, was being finalized for release. His responses to my questions are in Part 2: Interview with Ahmed Gabr.]

It will be up to Guinness to investigate the allegations that have been leveled, and decide whether Gabr actually completed a world record deep dive or not. Given the newly revealed evidence, and Gabr’s lack of response, he will likely face a large degree of skepticism on the part of the technical diving community until the truth is known and the issue resolved.

I asked Gomes, who’s spent the bulk of his thirty-some year career making deep dives for his perspective on the situation. After all, depending on the outcome of Guinness’ deliberations, his world record dive to 318 m/1,044 ft could be reinstated. We spoke by phone. “I never doubted Gabr’s record was valid,” Gomes offered. “I mean how could someone fool Guinness World records? It would take a well-planned scam, a hell of a scam. It would be just terrible. I mean how could you live with yourself? It’s just inconceivable.”

Read what Gabr has to say in Part 2: Interview With World Record Holder Ahmed Gabr

This story has also been published in DeeperBlue.com.

SEP 1, 2023—Editor’s Note: Guinness World Records finally reviewed and responded to the allegations re: Gabr reported record dive in early 2021, stating there was “no conclusive evidence establishing foul play.” See: Guinness World Records concludes review into deepest scuba dive (male) record. The trouble is that their investigation did not address specific allegations, nor did they interview members of Gabr’s support team who raised concerns. Guinness World Records did not respond to InDEPTH’s queries regarding their investigation. As a result, questions about Gabr’s dive remained unanswered.

Dive Deeper:

Scuba Sam’s Analysis of Gabr’s Dive

Where no one else has gone before | Ahmed Gabr | TEDxAUC (In Arabic)

Ahmed Gabr discussing breaking the world record on his dive to 332m: the planning, the preparation, helium, and the determination.

Ahmed Gabr’s Training dive before 332,5 meters dive- the new world record.

Nuno Gomes World Record Sea Dive: World Record Sea Dive (part 2) (Video)

Nuno Gomes’ World Record Dive 318.25 m “Beyond Blue” final episode (Video)

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s editor-in-chief and an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving (1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012, and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018. In addition to his responsibilities at InDepth, Menduno is a contributing editor for DAN Europe’s Alert Diver magazine and X-Ray Magazine, a staff writer for DeeperBlue.com, and is on the board of the Historical Diving Society (USA).