Exploration

Finding the Wreck of the “Admiral Knight”

Professional archeologist and tech diver Ewan Anderson recounts the tale of finding the early 1900s steamship the Admiral Knight in British Columbia waters in the spring of 2020—a collaboration of the British Columbia Underwater Explorers (BCUE) and the Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia (UASBC). It’s a tribute to the power of “Citizen Science,” and the joys of diving with purpose. Here’s how they found it.

By Ewan Anderson

“Well… I might have a target for you,” read the fateful email that led to our search for the wreck of the early 1900s Admiral Knight steamship.

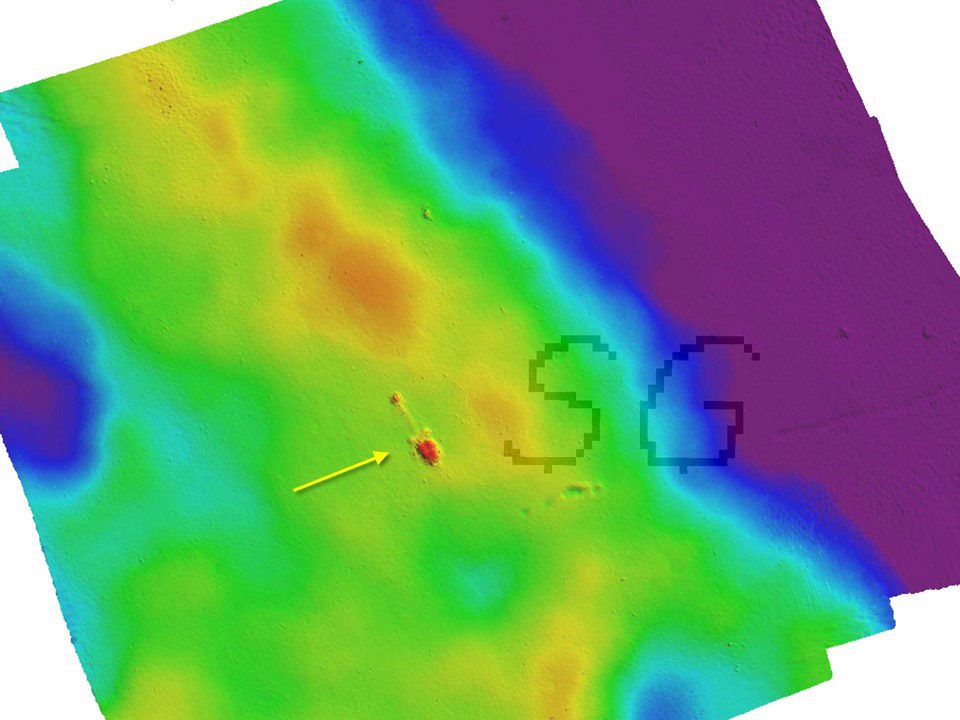

It was 2019, and Craig Lessels of the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) had been reviewing multi-beam sonar bathymetry datasets — basically, maps of the seafloor — when he noticed a cluster of features lying on the otherwise sandy seafloor, east of Galiano Island in the Salish Sea off the west coast of Canada.

Thinking the Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia (UASBC) might be interested, he forwarded what he had found to UASBC Explorations Director Jacques Marc.

As it turned out, the UASBC had, since 2006, been looking near this location for the Admiral Knight, a steam-powered freighter that sank after an explosion in its engine caused a catastrophic fire on board.

The Search

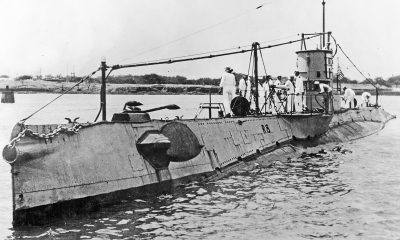

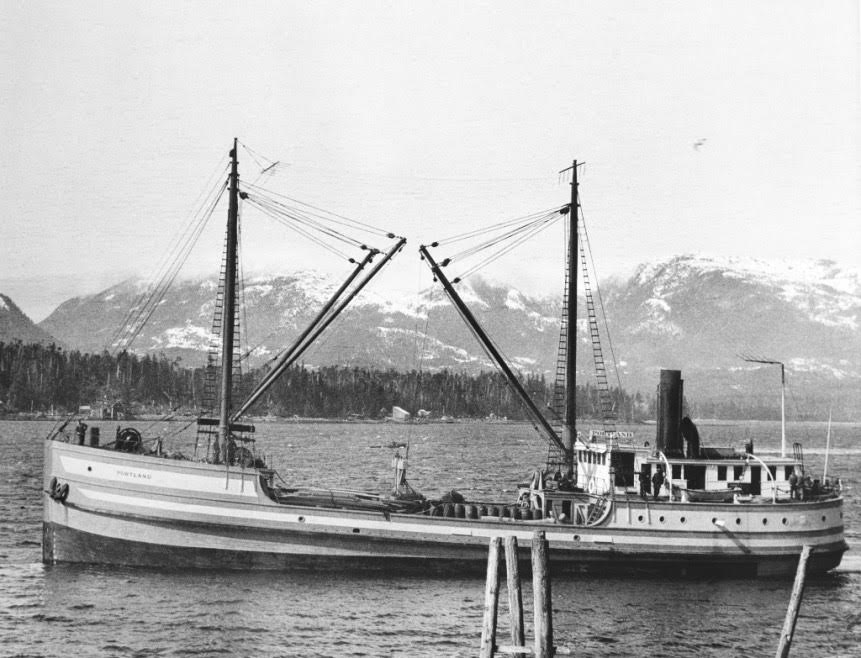

The UASBC search began, as usual, with some serious background research. The research turned up a wealth of information about the vessel’s origins and destruction in 1919. Launched by the Westward Navigation Company of Seattle in 1916 as the Kuskokwim River, the 43 m/142 ft long wood hulled, diesel-engine powered vessel was built to provide freight service between Puget Sound and Alaska. It was re-powered with steam engines in 1917 and renamed the SS Portland, and then renamed the Admiral Knight in 1919 after purchase by Alaska Pacific Fisheries, who may have used it to supply their canneries in Alaska.

On July 26, 1919, a fire broke out in the Admiral Knight’s engine room while the freighter was underway from Seattle to Ketchikan. The crew of 21 barely made it off the ship before it was engulfed in flames; the last six men leaped off the foredeck onto a boat dispatched by the local steam ferry just in time to be saved. Three days later, mariners were still being warned of the burning hulk drifting between Vancouver and Vancouver Island, but there was no sign of the ship by July 30.

The Admiral Knight was forgotten until the late 1950s when a group of divers explored a site near Galiano Island where a local fisherman reported to have snagged his gear on a wreck. In an interview in 2006, one of the divers remembered seeing an intact wooden hull and some machinery matching the Admiral Knight’s description at depths of 55-64 m/180-220 ft; although this firsthand account came with the caveat that they were “narked out of their minds.” This general location became the focus of the UASBC’s field surveys over the next few years, including searches using towed side-scan sonar in 2006 and a multi-beam sonar survey by Parks Canada’s research vessel, the MV David Thompson. Those searches did not locate anything resembling the Admiral Knight wreck, and its location remained a mystery until CHS’s review of data from deeper water in 2019, just beyond the UASBC’s previous search areas.

The CHS target sits in 57 m/187 ft of water, which puts it beyond the range of the UASBC Explorations “regulars” group, some of whom have been exploring and documenting underwater maritime heritage sites in British Columbia and Alaska since the early ‘80s. As a UASBC Explorations regular myself — albeit with only 15 years’ worth of expeditions in my dive log — and member of British Columbia’s close-knit Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) technical diving community, Jacques turned the project over to me and wished me luck. I had been bothering Jacques for several years to give up his wish list of deeper shipwreck targets, and it appeared that this was my chance to prove that GUE tech divers on Vancouver Island could make a significant contribution to the underwater cultural heritage record on B.C.’s coast.

The Plan

We were ready! In short order, I had a team of qualified and enthusiastic GUE divers, a dive boat, and a dive date in April 2020. And then we were interrupted by the pandemic. Organised diving took a big step back while everyone tried to figure out how to navigate a variety of restrictions and act responsibly in the face of this century’s biggest global health scare. Focus shifted to community-building through impromptu dives, and the big projects, like our plan to identify the Admiral Knight, took a back seat.

Dive boats available for projects around south Vancouver Island changed, too. GUE instructor evaluator and Vancouver Island resident Guy Shockey bought a boat, the Thermocline, brought it up to the island from Puget Sound, then learned how to drive it (possibly in that order). While the boat was still just a twinkle in Guy’s eye, he told me he hoped to make Thermocline a platform for divers to do world-class diving, but for that to happen it was up to the local GUE community to demonstrate that we had interesting project dives to do. He and I agreed that identifying the Admiral Knight fit the long-term community goals perfectly. Soon after the Thermocline arrived at its permanent home in Vancouver Island’s Maple Bay, Guy started referring to himself as “The Boat Driver,” so I knew he was seriously committed.

The Dive

By early 2022, our diving activities on the west coast were back to their pre-pandemic norms, and the way seemed clear to dive the Admiral Knight. So, on a sunny weekend this past August, with water as calm as glass, I found myself dropping through the cool, emerald-green depths towards the bold future of underwater archaeology in my backyard.

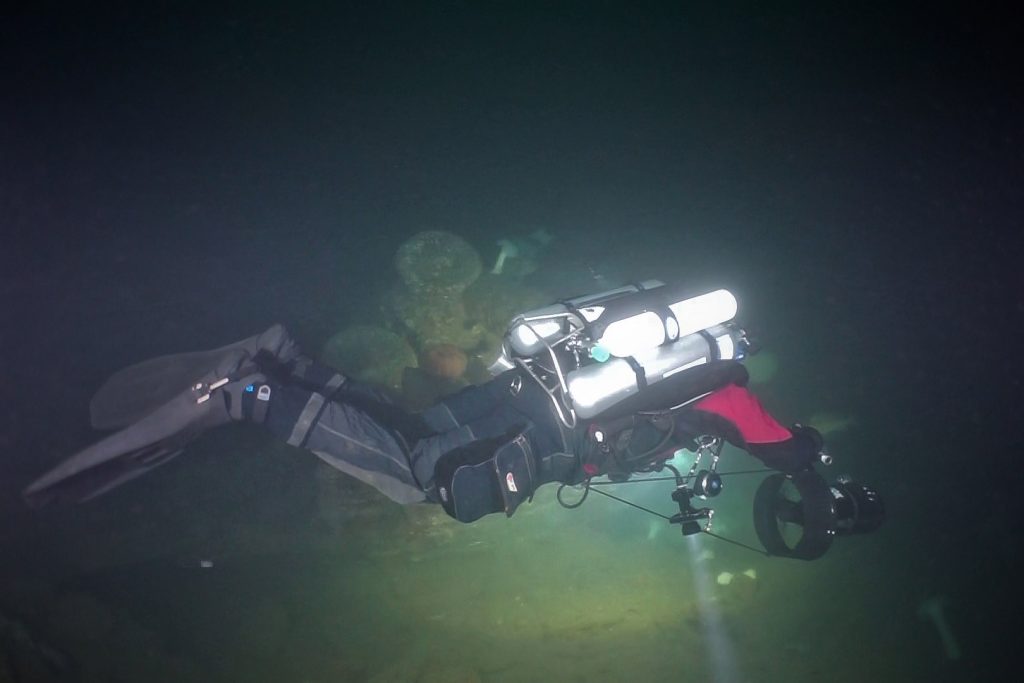

Dropping down the shot line with me was Jason Cook, an instructor and fellow rebreather diver. As we descended, I had a head full of plans and checklists, and handfuls of equipment. Try as we might to keep things simple, we were determined to complete a minimum number of tasks and needed the gear to pull them off. In addition to our JJ-CCR rebreathers and bailout cylinders to do the dive, we had a full-frame camera and two pairs of large video lights to document the wreck (if it wasn’t just a pile of rocks we were dropping onto). Jason had a 120 m/400 ft reel in case The Boat Driver dropped the shot in the middle of nowhere and our identification dive turned into a search for, well, anything. I had an additional large surface marker buoy (SMB) stuffed in my left thigh pocket, which we planned to launch without a line attached to signal the next dive team that we’d found something worth diving. We each had a diver propulsion vehicle (DPV) to drag all this stuff around if the current picked up (strong currents are common in our region, but also highly localised, and nobody was sure when slack tide was at this new site).

The visibility on the descent was just over 20 m/60 ft, which is fantastic no matter where you are in the world. As we passed 40 m/130 a huge grey shape swam right in front of me — a shark! — no, just the biggest lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus) I had ever seen. As the monster fish disappeared, we hit a layer of low-visibility water hovering about 5 m/15 ft off the seafloor. It appeared we were going to be diving in the dark — and the cold, since it was also suddenly only 9° C/~48° F. Finally, the shot appeared below us, lying on a featureless, sandy plain. There wasn’t even a pile of rocks pretending to be a wreck in sight.

Like the optimist he is, Jason quickly got out his reel to tie-off and start a search. I, on the other hand, stared dejectedly into the gloom, where I could just make out some white blobs in the distance. But wait a second — the blobs must be plumose anemones (Metridium farcimen), and anemones must be attached to something! I got Jason’s attention with a flash of my light, and we headed off towards the anemones.

It turned out that our search for the wreck was brief — the anemones were only about 10 m/30 ft away, attached to a driveshaft just forward of a small steel propeller. It was a convenient place to tie off the reel, and an auspicious start to our dive. I deployed the SMB, which, unencumbered by a line attached to a spool, careened to the surface, and launched, like a small pink ballistic missile, out of the water beside the waiting Thermocline. The second dive team — Lee Critchley, Conor Collins, and Colin Miller — were into the water in moments to start their dive.

Back at the wreck site, Jason and I started the next phase of our dive: a visual survey of the site. Firing up the DPVs, we followed the driveshafts forward from the propeller. The shafts disappear under a jumble of machinery that will need a more thorough survey to sort through. The large water-tube boilers appeared next, standing upright on their fire-boxes about 2-3 m/6-10 ft proud of the seafloor. Patches of the relatively thin steel encasing the boilers had corroded away, revealing intricate tubing that was cutting-edge boiler technology in the early 20th century. Winches and engine parts formed another pile forward of the boilers, beyond which was the relatively featureless expanse of seabed corresponding to what was once the vessel’s hold. About a minute later, we rounded the forecastle which sat upright about 3 m/10 ft high, the foredeck winch still in its original position. We completed our circuit with a straight run back to the stern, spotting the second drive shaft and propeller.

As the second team arrived on the bottom, Jason and I lit up the wreck with our video lights. I wanted to document the visual survey we’d just completed, so I coordinated with Jason to do a re-run at slow speed. He led and illuminated the wreck, while I followed with the DPV-mounted camera and lights. Keeping Jason in frame made for a good scale reference as we slipped slowly past century-old rust and watchful fish. The end of our video captured the other team swimming around the boilers. Conor was taking still photos while the others inspected the machinery and puzzled out what they were looking at.

And just like that, it was time to go. Leaving the reel for the other team to collect, Jason and I headed back to the shot line and had the usual brief conversation confirming our decompression plan before leaving the bottom. The ascent took us back up to the relatively crystal-clear water above 45 m/150 ft. We crossed the thermocline around 15 m/50 ft and completed our deco in 18°C/64° F water and dappled green sunlight.

The Rediscovery

Back onboard the Thermocline, we all agreed that the first day of diving was a great success. We had identified a wreck and concluded that it was worth diving again; but was this definitely the wreck of the Admiral Knight? We thought so: it is a steam-powered, twin-screw vessel of the correct size. And we knew the burning hulk was seen by several witnesses drifting in the vicinity of our wreck site in late July 1919. More definitive evidence of the wreck’s identity lies in a closer inspection of the surviving equipment and the cargo. We surfaced with about 10 minutes of good-quality video and some still photos, which Jacques will want to review and comment on.

The two-hour sail back to the dock, and lunch at the marina pub gave us plenty of time to debrief and discuss the details of our dives. We sketched out the goals for diving the next day, and I included a somewhat ambitious list of items to measure and a plan to create a 3D model of the boilers.

Jason and I were back in the water 24 hours after our first dive on the wreck. The shot line had landed right behind the boilers, so we got to work immediately. This time, we planned to document the boilers using photogrammetry. Issues with camera float arms the previous day meant we were not able to carry as many big lights, so I had the camera while Jason handled most of the lighting.

The somewhat poor visibility and missing lighting (though we still had a lot of lights) meant we had to get relatively close to the wreck for well-lit photos. And since the boilers don’t cover a very large area, I decided to park the DPVs and kick. In hindsight, the DPVs might have made things easier, but I didn’t notice the current sweeping across the wreck until after the kicking started. I’m not beyond second-guessing myself underwater, but with only 30 minutes of bottom time to set-up and complete the photogrammetry, there wasn’t a lot of time to reorganise and restart the work. In the end, we managed to get about 470 reasonable photos for our modelling project.

The second dive team, Guy and Jim Dixon, arrived on the wreck a few minutes after Jason and I started taking photos. Guy and Jim had the straightforward task of just enjoying the dive. This seemingly simple job is a common assignment on UASBC dives: divers who are unencumbered with cameras, lights, measuring tapes, and other documentation equipment are free to explore and are likely to notice important features that busy diver-photographers might miss. This team spent some time inspecting two “block” features that I had noticed the previous day; sitting forward of the engines and boilers, the blocks could have been the remnants of the vessel’s cargo, which would be an unusual find because we don’t often see intact cargo on our wrecks. We didn’t manage to solve the mystery on this expedition, and even with Guy and Jim offering detailed descriptions, we’re all still scratching our heads.

Although there were only a handful of divers who made it down into the wreck in August, dozens of people have contributed their time and energy over the last decade and a half to making these successful dives possible. To dive into the unknown just to see what’s there is one thing, but to dive with purpose and come back with valuable information requires dedicated research and planning. Credit for our success (and the pressure to succeed!) in search for the Admiral Knight is largely due to Jacques Marc and other researchers at the UASBC who laid the groundwork for the project.

There is much more to come. We’ve proven that we can add deeper sites to the list of the UASBC’s potential expeditions. Jacques and other UASBC volunteers are turning to the archives to find more targets. By extending the range of what is possible for the local community, we also open the door to exploring deeper into history. Indigenous peoples have lived around the Salish Sea since time immemorial, as indigenous elders and cultural leaders say, and their cultural inheritance includes documented sites spanning the last 14,000 years. The connection Salish peoples have with the sea around us is undeniable, yet tangible underwater heritage sites other than shipwrecks have barely been explored.

As for the Admiral Knight, any uncertainty about the wreck’s identity may be beside the point. The wreck still makes for a great dive, and although it is relatively deep for most divers, many in our local dive community are qualified – or will be soon – to dive it. It’s worth the effort just to see the intact boilers and the entire vessel’s contents laid out on the seafloor, just as they were 103 years ago. The intact sections of wreck and potential cargo provide opportunities for further study and research as well.

See companion stories:

Building Community Through Project Diving By Guy Shockey

Introducing GUE’s New Project Diver Program By Francesco Cameli

Dive Deeper

InDEPTH: How to Become an Explorer: Passion, Partnership, and Exploration

Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia

Marc, Jacques and Warren Oliver Bush (2021) Historic Shipwrecks of the Southern Gulf Islands of British Columbia. Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C.

Ewan Anderson is a professional archaeologist whose work focuses on assessing and mitigating development construction impacts to cultural heritage sites in British Columbia. A consultant for all levels of government, a variety of industries and Indigenous communities, his expertise is in cultural heritage law, cutting edge archaeological methods and Indigenous peoples’ relationships with archaeology and those who practise it.

Ewan is passionate about diving – especially when combined with underwater cultural heritage projects. He is a GUE certified JJ-CCR diver and IANTD certified cave diver. His diving has taken him around the world, even though everything he needs – from wrecks to caves – can be found within a few hours of his home in Victoria, on Vancouver Island.

His professional work and diving almost never mix, for which he is often thankful. Ewan pursues his interests in underwater photography, underwater photogrammetry, and advocating for conservation of marine environments and underwater heritage, free from the yoke of capitalist overlords. He is a regular volunteer on Underwater Archaeological Society of BC expeditions and has served on the Society’s board of directors since 2018.