Latest Features

Finessing the Grande Dame of the Abyss

Poetic Italian explorer and tech instructor Andrea Murdock Alpini shares the culmination of his lifelong dream to dive the storied wreck of the Andrea Doria. His goal? Assess what is left of the slowly deteriorating Grand Dame. He contemplates her fading beauty in three bold dives—Certo, il giovane esploratore divenne poetico.

Text by Andrea Murdock Alpini. Historical Images: Ansaldo Foundation. Other images courtesy of PHY Diving Equipment.

The day we left the mooring lines on the ground in Montauk, I was reading the Antarctic Diaries to trick myself into being patient. After four years of worry and work, we were finally moving. I have devoted all of my strength to this endeavor—and I hope we’re successful.

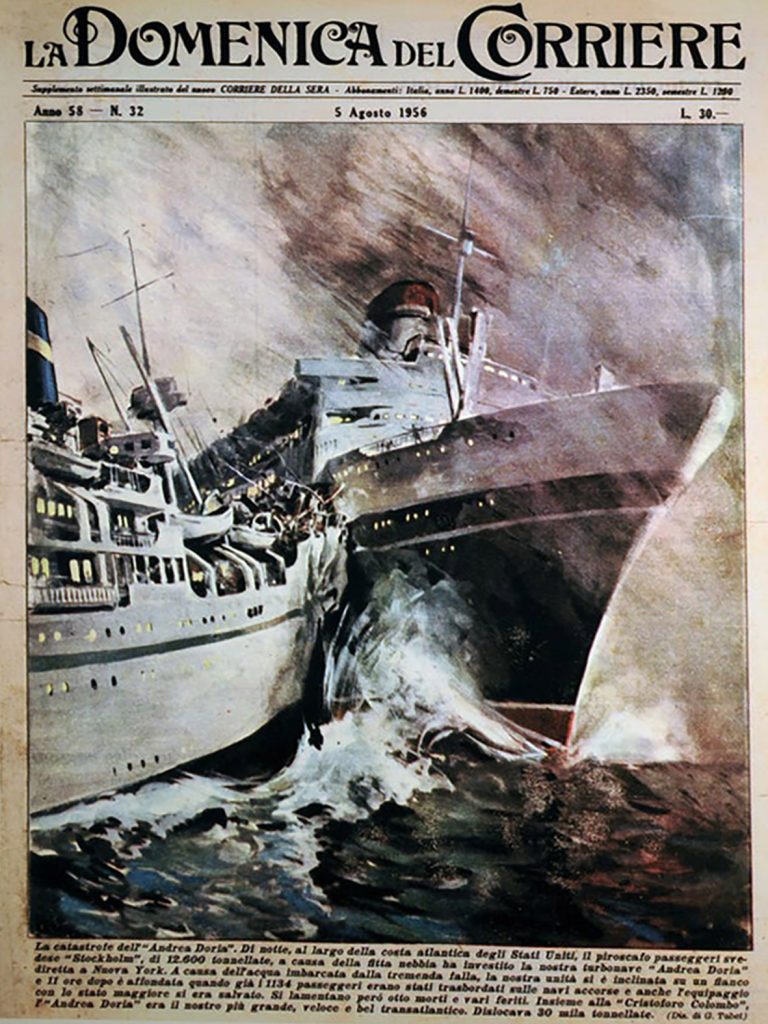

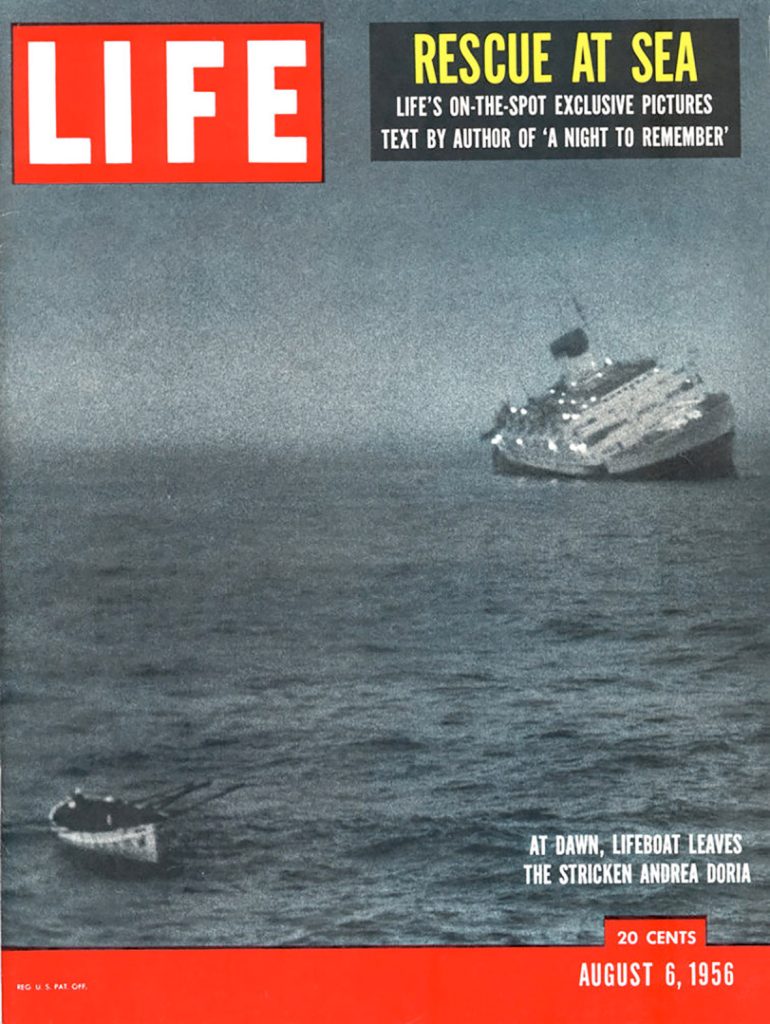

On July 25, 1956, the SS Andrea Doria—a microcosm of Italian cultural, social, political, economic, and manufacturing sensibilities—sank off the coast of Nantucket Island. Referred to as “The Renaissance Ship,” she made 100 successful transatlantic crossings between 1953 and 1956. Initially, it seemed that her 101st voyage would be no different. However, she tragically collided with another ocean liner in the summer fog, sinking 74 m/243 ft.

Many refer to the Andrea Doria as diving’s K2 or Everest. Why these mountains and not another rugged and difficult-to-reach peak? Perhaps the comparison pays tribute to the wreck’s fraught conditions—swift currents, poor weather, and freezing New England waters—Yes! Yes, and its formidable roster of brave, lost adventurers (sixteen and counting, to be exact).

And, K2 is often dubbed “The mountain of the Italians,” after all.

Doria Dreaming

It is September 2022, and we’re finally anchored above the Andrea Doria, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s been a lifetime dream but I am finally here. Getting here was a feat. Diving here will be, too.

Safety is more than just an implication for dives on the Andrea Doria. We’re 72 km/45 mi from the coast. The current is ever-present and strong—determined to carry you miles from the boat further into the boundless and rough ocean. By comparison, depth and bottom time feel like secondary concerns.

This is my third dive on the Andrea Doria. But my journey to this wreck has been long. Plunging into the water, my mind races with a tumult of thoughts. I’m heading in search of what is left of the Grande Dame.

Beware the Current

What keeps most divers from reaching Andrea Doria? In one word: Current. Swift and unceasing, it’s the first consideration to be made before an expedition on this wreck, in my opinion. Misinterpreting the current can produce a total débâcle. This isn’t a dive for the impatient—it’s often necessary to wait out the current, outlast the temporarily turbulent and overwhelming flow, and wait to enter calmer waters.

On past dives, I’ve seen the water roil on the surface and toss ballast lines as if they were straws. I’ve also seen the current calm completely in an instant.

Mustering the Courage

After my first dive I had reviewed my objectives—considering both current and conditions. I had been slapped back by the Grande Dame herself, and so I tried to find the motivation to face this second dive with the best possible approach. Come on! It’s just the cursed current!

On my second, the visibility had been so poor that I cut my bottom time to avoid unnecessarily long decompression. I knew I wouldn’t have captured any good images: just unclear shots of the wreckage.

I’m determined, therefore, not to waste this chance, my latest opportunity–perhaps my last. I want something more from Andrea Doria, and I’m hoping she wants the same from me, too.

Third Time’s a Charm

When I saw the wreck for the first time, I laid my hand on the left hull, whispering, “And so, you are Andrea Doria.” I knew a lot about the ship, but nothing about the wreck—at least not until the first time I met her.

But, that was then. I’m on my third dive, and now that I’m in the water, I know something has changed.

The water is a different color, a different density. Above all, the current is much less intense. Perhaps it’s even disappearing—a stretch that has taken me two minutes in the past takes me less than a minute to cover. For the first time, the surface of my mask isn’t covered with plankton and nutrients. I can finally see. At 26 m/85 ft, I look up and find a straight, taut, unmoving anchor line.

Proceeding lower, the line still isn’t moving. I can’t believe it; this must be the opportunity I’ve been waiting for. It’s finally time to see the propeller.

I count the cleats—first two, then three.

And here we are! It’s time to cross the keel en route to the left propeller. The current is low under the wall, perhaps only one knot—nothing compared to the four and five-knot flows of my previous two dives. How intense will it be beyond the bulkhead?

On previous dives, when I dared to peek over the wall, I felt the current trying to tear the skin from my face. Now, when I brave a hesitant glance, with both hands firmly gripping the wreck, I don’t feel hostile forces. In fact, just the opposite. Today is a gift.

Crossing the keel is typically laborious, but with visibility somewhat intact, I can move efficiently. Along the hull, the current picks up—just as expected. I continue on, finning in the direction of the propeller.

Within a few minutes, I’m at 70 m/230 ft. Joe Mazraani suddenly appears from the black, calling, “Andrea! It’s here!” Despite nearly a hundred dives on the wreck, I know he’s never experienced anything like this. It makes the journey all the more meaningful.

I immediately lay eyes on two shovels and start counting the others—I’m starting to film. Upon discovering a thin, precise, powerful blade, I feel ecstatic.

I turn to see the propeller, and for a moment I feel like Vaslav Nijinsky. It’s so big that I can’t see it all at the same time. Somewhere, under the soft blanket of anemones, “Genoa” still adorns the hull.

The bulb tapers like a bullet. It’s beautiful and refined—like the architecture of Michelangelo and the engineering of Leonardo. Even individual details embody the ship’s allure.

Beautiful Ship, Marvelous Wreck

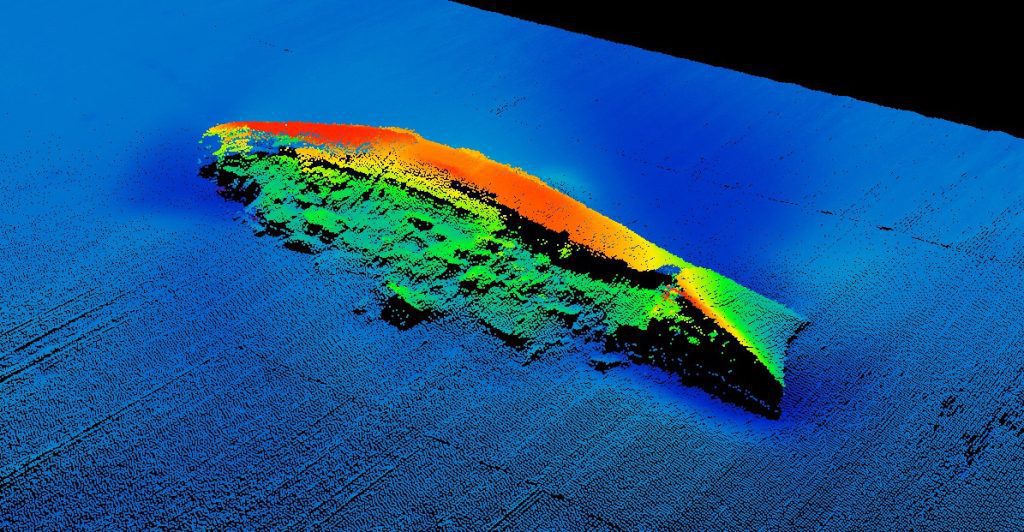

In July 2016, nearly six decades after she sank, ocean exploration company OceanGate ventured on three nearly four-hour underwater expeditions to the wreckage, capturing more than a dozen sonar images of the liner. The company’s findings were consistent with reports of intrepid divers’ observations: The Grande Dame of the Sea was rapidly deteriorating.

Recent underwater sonar imaging of the wreck reveals that this majestic ship is deteriorating more rapidly than originally thought—a large section of the bow has crumbled, and most of the superstructure has collapsed.

Andrea Doria was a floating masterpiece—so much more than just a luxury ocean liner. Underwater, she was perhaps an Eighth Wonder of the World. But today, devastating currents and ocean storms have nearly totally reclaimed her form.

Yet, a masterpiece remains in the details. Like the works of a Renaissance master, no one needs to see every brushstroke to understand the beauty of the whole picture: even a part of the whole is enough.

If you travel to Florence, Rome, Milan, Venice, Naples, Palermo, Urbino, Parma, or Genoa, you’ll catch a glimpse of the greatness of Italy that was. You’ll discover the same on the Andrea Doria. She, too, exemplifies the Italian spirit—what it means to be Italian.

The Boot has something to offer to anyone open to learning about its cultural sensibilities, despite some natives’ cynicism. But, many say that seeing the Andrea Doria today makes no sense because it’s disappearing—I defend that by suggesting that more divers should see it before it disappears.

Seeing the Andrea Doria is like seeing the Colosseum in Rome; even if its architecture constitutes only a fraction of the former Teatro Flavio, the remains make their own kind of sense, and seeing them feeds one’s soul. American architect Louis Khan describes “Beautiful buildings, marvelous ruins.”

The Andrea Doria is a beautiful ship and a marvelous wreck.

My dream had always been ahead of me, on the run and out of reach. To spend a moment in unison with my dream—to reach out and touch it—was nothing short of a miracle.

Dive Deeper

Journal of Ship Production and Design: The Decay of the Andrea Doria by Philip Sims, John Moyer, and Steven Gatto. J Ship Prod Des 26 (03) August 2010: 187–198

Other stories by the prolific Andrea Alpini Murdock:

InDEPTH: Hal Watts: Plan Your Dive

InDEPTH: Tridente D’Oro: Underwater Tradition and Innovation

InDEPTH: I See A Darkness: A Descent Into Germany’s Felicitas Mine

InDEPTH: Stefano Carletti: The Man Who Immortalized The Wreck of the Andrea Doria

InDEPTH: No Direction Home: A Slovenia Cave Diving Adventure

InDEPTH: My Love Affair with the MV Viminale, the Italian Titanic

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and PSAI technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of PHY Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. He published his first book, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti (2018) and IMMERSIONI SELVAGGE, published in the Fall of 2022.