Cave

Stoned: The Adventures of Wes Skiles and the US Deep Caving Team

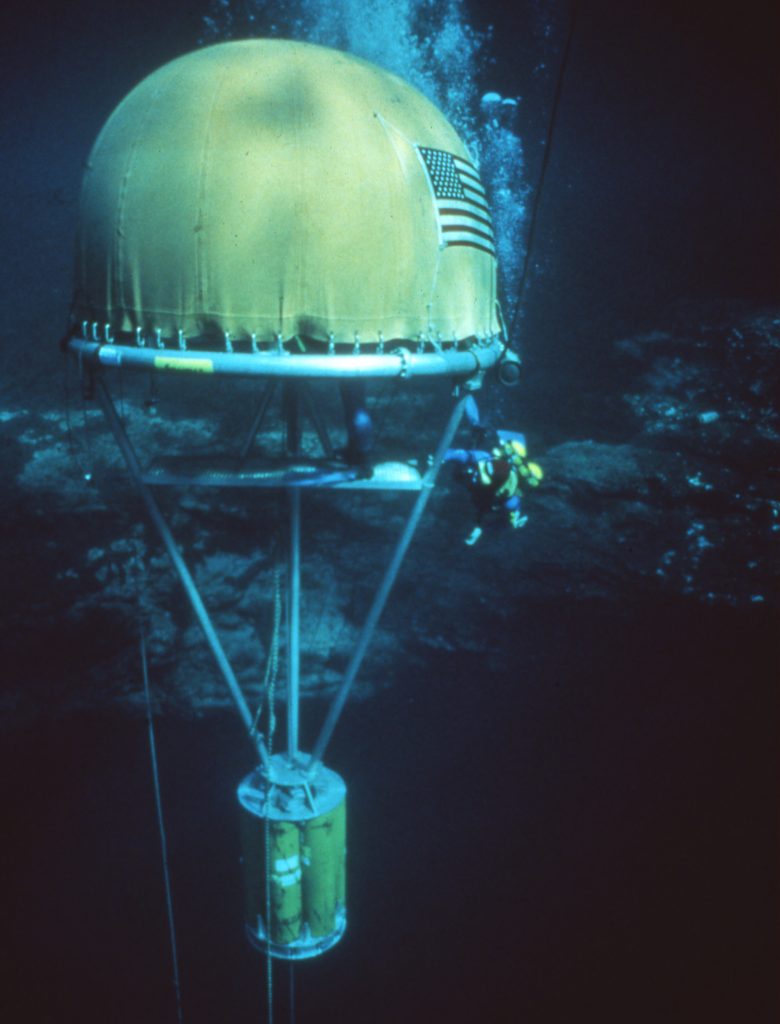

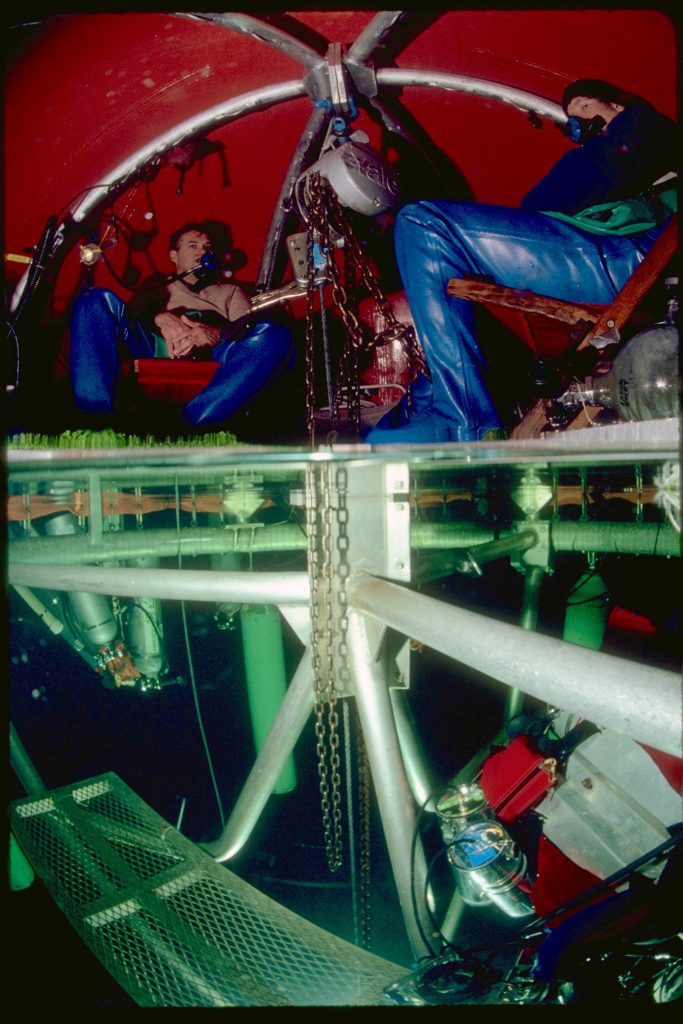

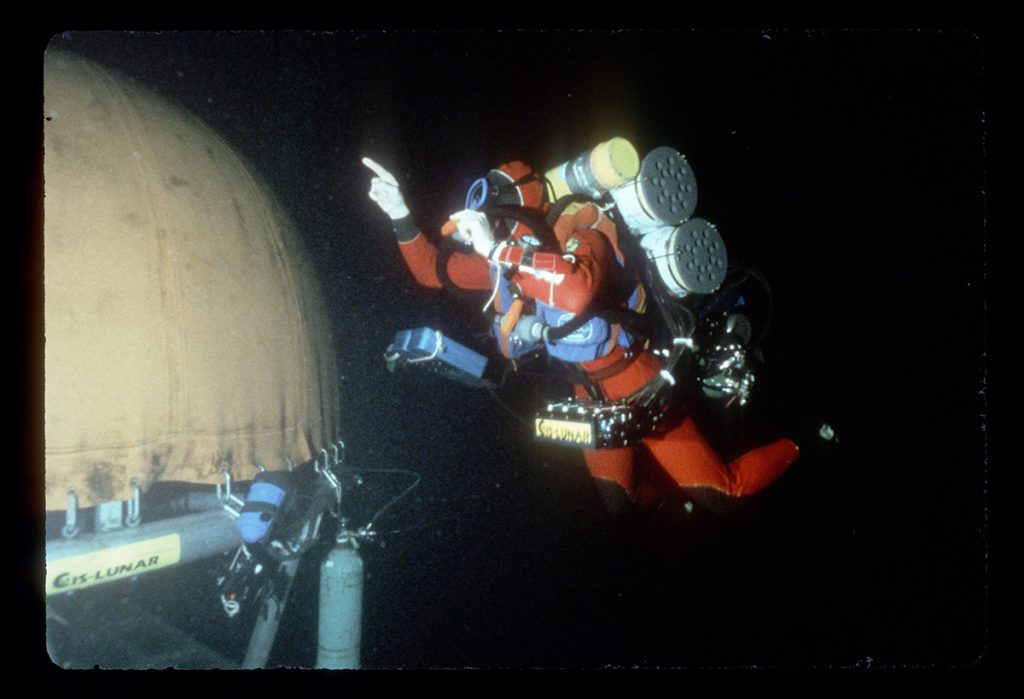

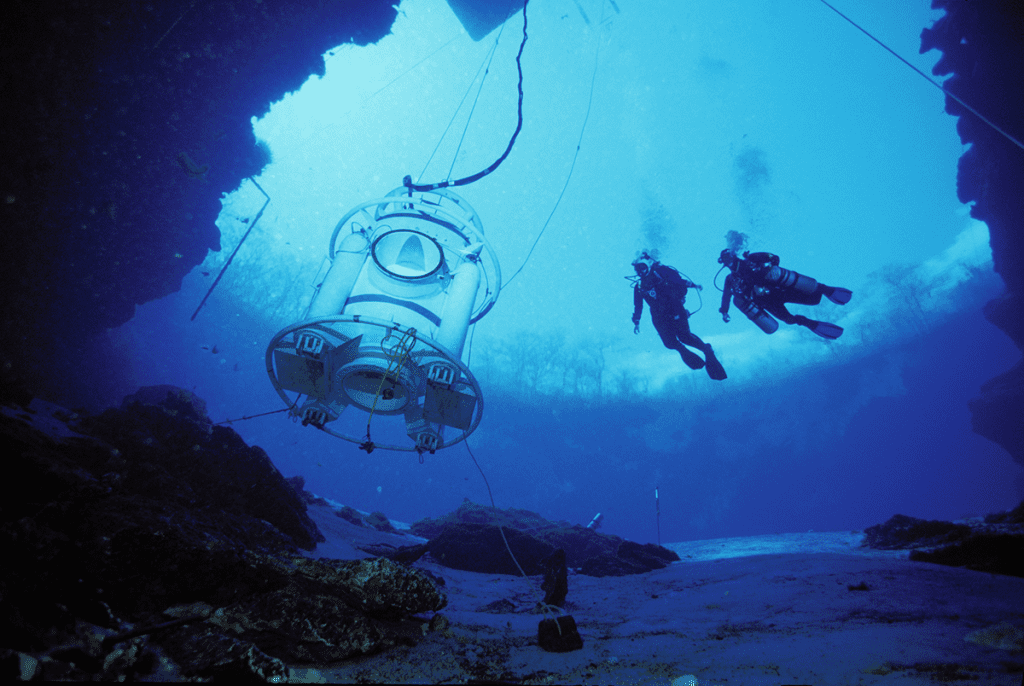

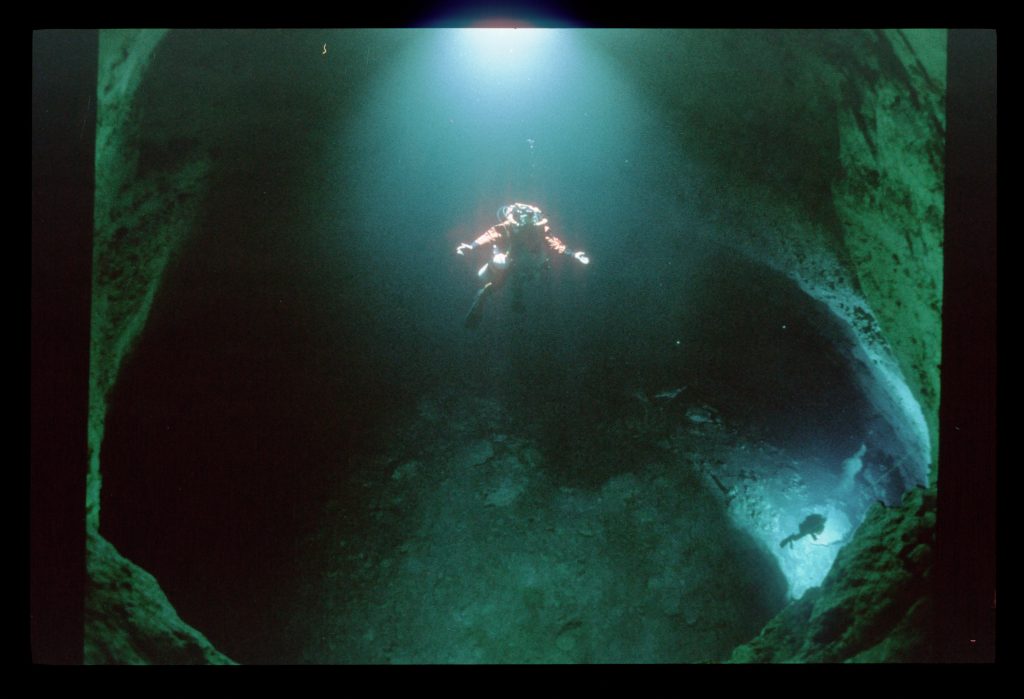

Text by Bill Stone, July 28, 2010. Images from Wes Skiles courtesy of the United States Deep Cave Diving team. Header image by Wes Skiles: Looking up towards the entrance of Wakulla Springs with habitat in view. A photo from this series was used in a Rolex ad featuring Bill Stone.

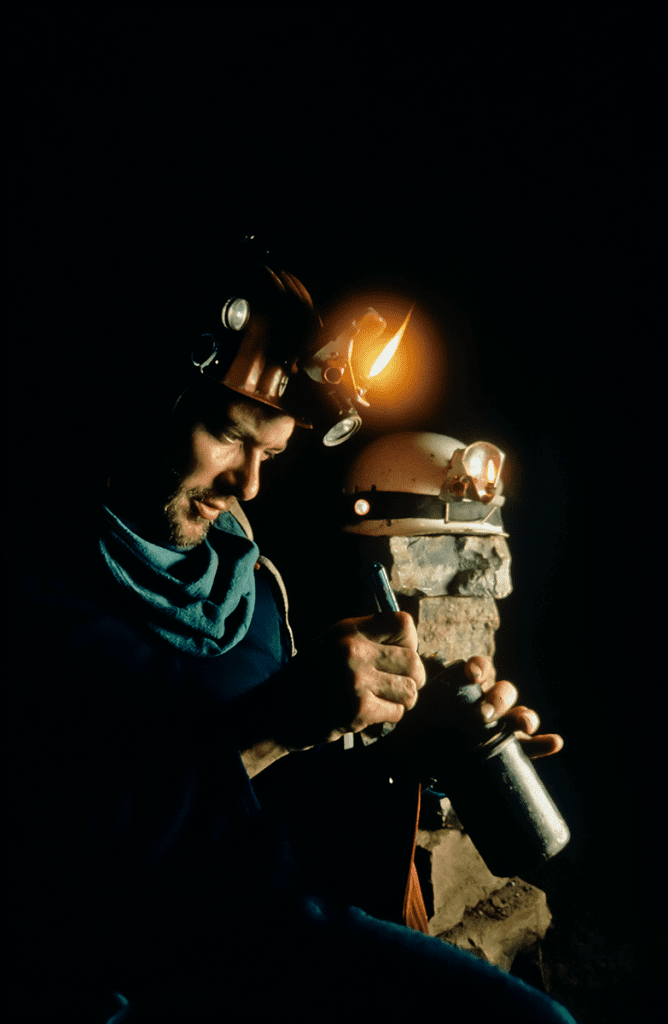

It was in the fall of 1980 that I first met Wes Skiles. I had driven down to Jacksonville non-stop from Maryland to continue training in deep diving with Sheck Exley. Sheck was teaching me how to dive deep on air for an expedition I had planned for 1981 to the San Agustin sump in Mexico. He recommended I pick up a set of twin 104s for work in Florida and went so far as to recommend a dive shop where I could get them: The Aquifer Dive Center in Jacksonville. It happened to be the dive shop owned by Clark Pitcairn, who was Sheck’s partner at the time on several pioneering, long stage dives. Wes worked for Clark and split his time equally between surfing and cave diving – getting off once a week on Wednesday evenings with Clark to dive a spring somewhere or the other in the Wild West that was spring diving in north Florida in those days.

So, at that time, Wes was a 23-year-old cave diving surfer bum, doing anything for a weekly cave diving fix and catching the next wave. Like several of us who were lucky enough in that era, Wes had the good fortune of being an apprentice to Sheck Exley. But Wes went further than most of us and became Sheck’s protégé—a redneck protégé with a wicked sense of humor.

The Wakulla Project 1987

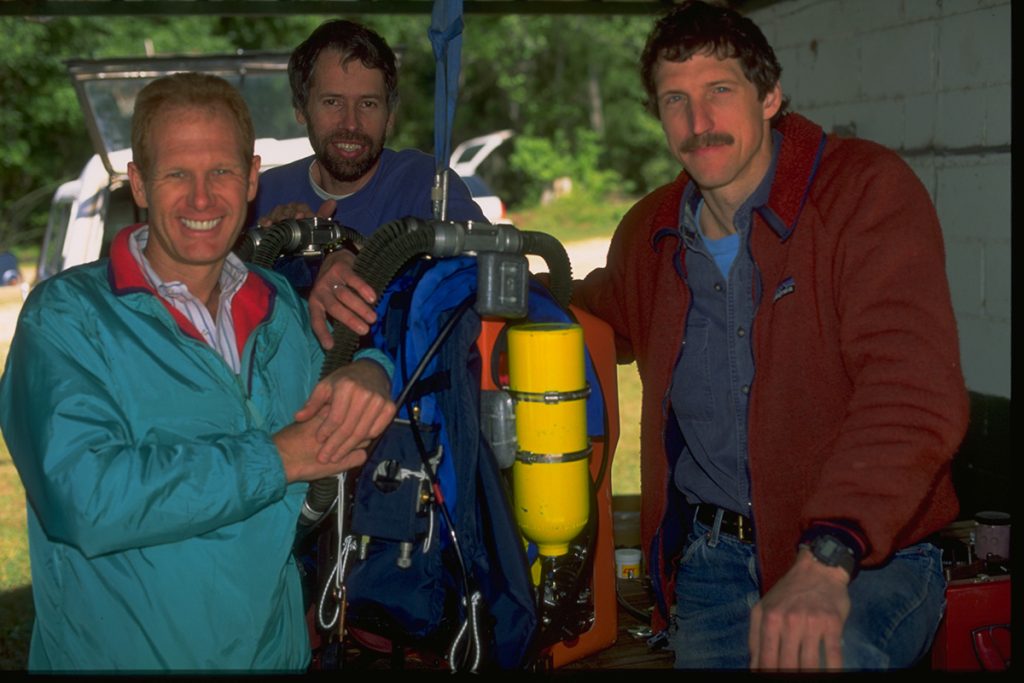

I lost track of Wes until the fall of 1987 when an unusual series of events led to us being granted a three-month permit to explore Wakulla Springs. By that time, Wes was well known as one of Florida’s top cave divers, and there was little question he would be involved with the project. So was National Geographic. We had set up our headquarters in the small concession stand building left over from when Wakulla was a private resort.

The expedition was short on cash, and we had let this fact be known to our sponsors at National Geographic. At that time, the best known underwater photographer at National Geographic was Emory Kristoff. Not long after sending the emergency note to NGS, Wes and I were working on gear together in the concession stand when came a knock on the door. Wes went and answered it, and there, in a trench coat in the rain, was Emory Kristoff. He walked in and, doing his best James Cagney impersonation, said, “Da boys in DC heard your message, so dey sent me to deliver the money.” Whereupon he opened the trench coat and slapped a wad of $3,000 on the table. Then he turned to Wes and said, “Hey, kid, I hear you knows how to run a camera underwater?”

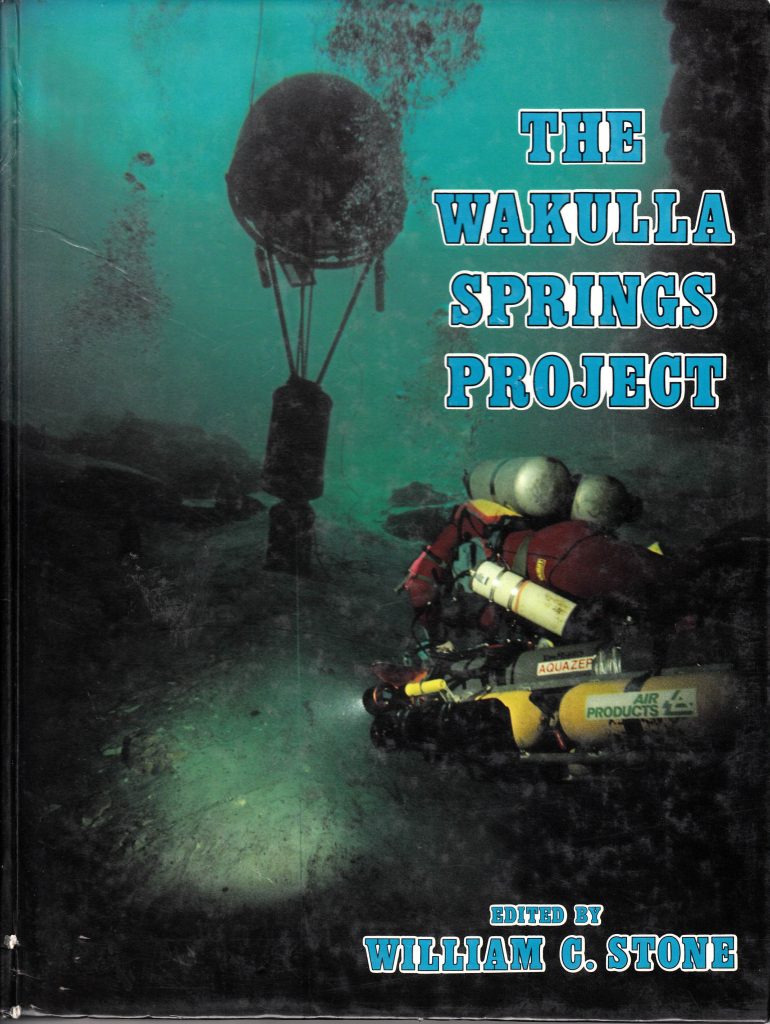

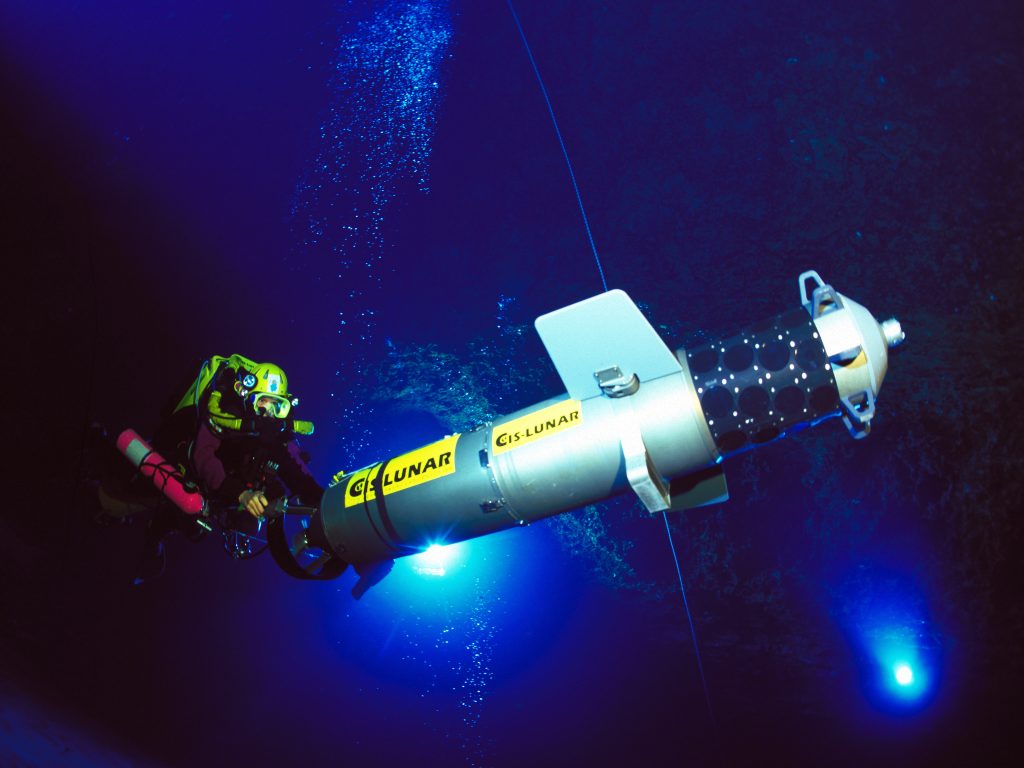

And Wes was stumbling for words. So Kristoff continued, “Well, de boys in de basement at 17th & M sent me with another present for yuz.” And he had his assistant outside bring in several boxes with $20,000 worth of Benthos deep submersible camera gear. He and Wes then disappeared for some time together and the next thing we saw was this tank sled that bolted under an Aqua Zepp carrying all this camera gear. With Emory’s encouragement, Wes set off on a mission—one that would become his life’s mantra—to get a series of powerful images that would turn heads at NGS. He got them, but the story got bumped because of the Centennial series of stories that came out that year. His shot, “Phantoms of the Cube Room,” taken in Sally Ward, and other shots of divers riding Aqua Zepps into the Grand Canyon of Wakulla—suspended in blackness as if flying in space—became the center pieces of the book that was written about the project. That book, propelled by Wes’s stunning photos, was one of the principal catalysts of what later became known as the “Technical Diving Revolution.”

One morning at Wakulla in the fall of 1987, we were having our usual pre-mission planning discussion at the lodge. Sitting in the sun room were Sheck, Paul Heinerth, Clark Pitcairn, Paul DeLoach, John Zumrick, Mary Ellen Eckhoff, Tom Morris, Wes and me. We were strategizing who was going to do what and when. Suddenly Wes got this look of apprehension on his face and Sheck said, “Wes, is there something wrong with this plan?” And Wes, yelling over his shoulder as he ran out the door, said “Oh crap ! My tanks !!” And we all saw him running down the hill to the springs where we had one of several compressors set up. Wes had put an empty set of twin 104s on charge, and since it was going to take a long time to pump, he had come up to the meeting,which had lasted longer than expected. When he returned, he had this sheepish grin on his face. Sheck, in his usual understated way, said, “I guess you over pumped them?” Wes, in his equally laconic way, said, “Well, I guess you’d like to say I hydro’d them. But since they didn’t explode, I figured, hell, why not keep the extra gas for a better safety margin today ?” There was a moment of True Wes.

Leo Dickinson was also there in 1987, filming a documentary with Wes’s help for HTV Britain. Following the longest exploration dive of the project—almost 1,400 meters from the entrance in B Tunnel—Leo interviewed Wes and said (when Wes had just turned 30), “Do you feel you’ll be able to keep this up— to continue exploring”? And Wes responded, on film, “As I get older, I know things will become more difficult, but we’ll just change that with technology,” and keep on diving.

San Agustin Expedition 1994

There was a long gap of time before I saw Wes again. It was Thanksgiving 1993, and we were testing the Cis-Lunar Mk4 in Ginny Springs before a planned expedition to Huautla in the spring of 1994. Wes and I went on a dive together, both with Mk4s, to the Hinckle restriction in Devil’s Eye and then coasted out. When we got to the entrance, and it came time for decompression, Wes told me he was going to use his normal air dive computer, since he did not yet trust the decompression algorithm that we had recently installed on the Mk4. I said, “OK,” and proceeded to surface 45 minutes ahead of Wes. He later explained that due to earlier decompression incidents he had to be conservative. I respected that decision as a sign of controlled discipline—something both of us had learned well from Exley.

The next time I saw Wes was at a barbecue at Woody Jasper’s in February 1994. It was a send-off party for two important expeditions that spring—for Sheck and Jim Bowden’s push on Zacaton—and for our project to Huautla. Late that evening, Wes broke out some videos he and Kenny Broad had collaborated on and with a tongue-in-cheek smile, warned us to learn from these videos so we would not make the same mistakes on the upcoming projects. One was the infamous “Jacque Eye-Ear” escapade in which a famous French free diver (played by Kenny) attempted to swim from Devil’s Eye to Devil’s Ear on one breath; and the second one “Captain Safety”—an insane underwater horror flick with monsters with glowing eyes and Aqua Zepps that flew upside down. Both used novel points-of-view that were early indicators of Wes’s genius behind a camera. His later artistic work “Little Devils” had a powerful visceral aura to it. Wes, understanding the power of the film, enjoyed pointing out that a certain portion of his growing public audiences seemed to leave halfway through a screening of “Little Devils” out of sheer claustrophobic anxiety.

A few months later, during much sadder times following the loss of Sheck in Zacaton and our Scottish teammate Ian Rolland in San Agustin, Wes came to Huautla. He arrived like the cavalry on a white horse— instilling new enthusiasm to a demoralized team. He was on official assignment from National Geographic and was determined to capture on film the essence of the undertaking and to buoy the spirits of those who chose to continue on. He succeeded in both. He knew exactly what he needed to get, and I watched as he spent 27 rolls of film and more than a week hanging on rope to get one picture of the entrance to the Sotano de San Agustin that he knew was a keeper. He did that 15 more times in other places and the result was the National Geographic story on the expedition printed in September 1995. I owe a great debt of gratitude to Wes for doing that. Had he not brought the team back together, it is doubtful we would have gone on to continue exploration beyond the San Agustin sump.

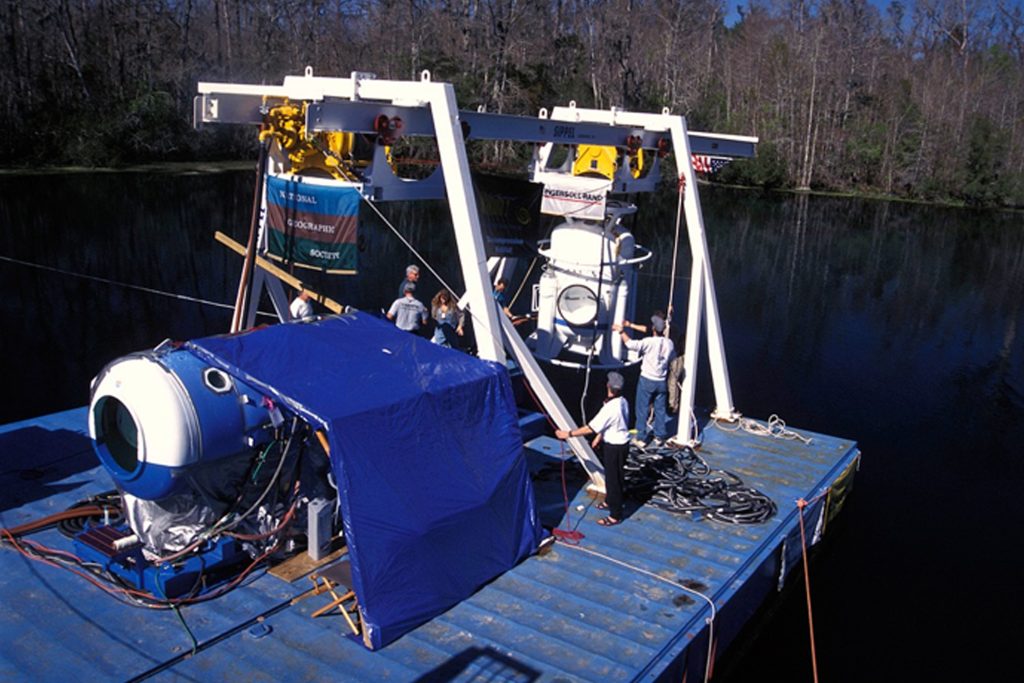

Wakulla 2 (1998-99)

I had the privilege of working with Wes again in 1999 at Wakulla Springs. This time he had a much more mature style and a crew of six working for him. But he carried that same gleam of excitement in his eye to be there where it was happening and the same determination to get the shot. He was now a regular with National Geographic, and his footage was at the heart of the hour-long documentary “Mapping the Labyrinth” that captured the essence of the effort to build the first 3-D cave map. I enjoyed the frequent evening campfires we had at Indian Springs—where the team was based for that project—with Wes telling tales of his upcoming projects.

Over the next decade, I did not see Wes much. But during this time, his reputation, his catalog of underwater films, and his print articles continued to grow to where he achieved worldwide recognition. He even occasionally stuck little jokes into his films to tease friends, like the hand-held sonar cave mapper in “The Cave.” I could see that wide “Wes grin” on the other side of the email as he wrote to me about that scene.

The day before Wes died, USA Today ran a major story on Wes, Kenny Broad, Brian Kakuk, Jill Heinerth, and their recent blue holes expedition to the Bahamas. The August 2010 issue of National Geographic Magazine boasted what may be Wes’s most stunning image ever on the cover, followed by a three-page fold out inside. He went out at the top of his game. The best underwater photographer on this planet.

I would have worked with Wes anywhere. Under any conditions. On this planet or off it. He was a true expeditionary man—a true brother in exploration. If there is life after death or existence in a parallel dimension, I know that Wes is out there now, showing them how to make perfect pictures. Carry on brother.

To explore more stories, documentaries, videos and articles by and about Wes Skiles click here: Celebrating Wes Skiles

William C. “Bill” Stone, PhD, P.E. is the CEO of Stone Aerospace, Inc. and Sunfish, Inc., both based in Del Valle, TX. He is an internationally acclaimed cave explorer and the president of the United States Deep Caving Team.