Community

Resurrecting a Ghost: The Launch of Ghost Diving USA

By Katie McWilliams. Photos courtesy of Ghost Diving USA unless noted. Header image by Jim Babor

Ghost Diving, formerly Ghost Fishing, has officially arrived in the United States. Naming Southern California as home for the United States chapter is not an expansion to a new territory; instead, it is a warm welcome home after a long journey.

Ghost Fishing first arrived in Southern California in the mid 2000s spearheaded by Karim and Heather Hamza. Their team, a group of volunteer technical divers, set out to improve the health and viability of the Southern California waters. The team started with the Infidel, a sunken squid fishing vessel near Catalina Island in 45 m/150 ft. They diligently worked to clean the Infidel which took almost two years. This victory was huge for their effort. Sadly, due to lack of funding, they were unable to continue other projects. Despite this hardship and some time away from their pursuit of the ghosts, Karim and Heather are back and more motivated than ever.

Heather’s passion is deeply rooted in her mission to advocate for animals. This passion has helped her to push through and focus on advocating for the animals that are often unseen. The marine life that goes undetected but is ever threatened in our oceans. These are the animals Heather makes very certain to see. Her passion and love for them is palpable; it radiates from her like the warmth of a sunny day. It beckons you to join her cause. This is what keeps the fire alive in her heart for Ghost Diving. She knows that she can turn the collection of nets and her experiences into educational opportunities. Heather’s aspirations for Ghost Diving USA include continuing to educate others regarding the threat of abandoned and discarded fishing gear, seeking legislative solutions to the problem, and ultimately, building an informed and empowered community that takes care of our oceans.

Karim thrives in situations that require precision and accuracy. He explains that for him, this new era of Ghost Diving is providing a fresh opportunity to build a community of elite divers that share a passion for and commitment to a great cause. He has the knowledge and experience to help train and mentor divers along their path to becoming ghost divers and intends to give all he can to the process. He wants to bring to fruition teams of divers who trust not only each other but also the process, as well as high training standards and passion for the cause. As Karim described all the things that a ghost diver needs to be, one of the original team members immediately sprang to mind, Jim Babor.

Jim recounted the arduous process that is becoming a ghost diver and being active with projects. He started with the project as a safety diver. The deep team would come up from the dive to the nets, and Jim would ascend with them through their scheduled decompression. He then progressed into his technical training and began photographing and documenting the work the divers were doing. Jim shared something that truly captures the essence of the passion needed to be a ghost diver. When asked about some of his most memorable incidents, he recounted the amazing experience of rescuing live animals by cutting them out of nets they were trapped in.. When asked what it felt like to cut an animal out of the net and watch it swim away, Jim was simply at a loss for words. We spoke on the phone and despite Jim’s reflective pause as he gathered his thoughts, it was apparent that the experience resonates with him on a deep level rooted in compassion. For Jim, the Ghost Diving USA launch brings his commitment and journey as a ghost diver full circle.

Helping to lead Ghost Diving USA into the future is scientific coordinator Norbert Lee, Scuba instructor, marine biologist, and active technical diver. To speak to Norbert is to feel his can-do attitude and realize his aspirations are rooted in protecting and fostering the growth of the underwater world while educating the community about ocean conservation. More importantly, his strong sense of commitment to the team effort shines through everything. In asking Norbert about his journey to becoming the US chapter coordinator, he cited the significance of the mentorship he has and continues to receive. This mentorship comes from a variety of sources including Pascal van Erp, the Hamzas and Jim Babor.

Norbert Lee’s goal is to collect data about the environmental impact of ghost nets and how their removal impacts the health and growth of a given area. By collecting this data, he is confident he can help to educate the community about the true impact of abandoned fishing gear. He does not want to stop with nets. He wants to help recover lobster pots and other fishing apparatus that continue to catch fish after being left behind. Through educating the community, he does not want to villainize or chastise commercial fishing but rather to build working, symbiotic relationships with fishermen. By working together, Norbert hopes to have the nets removed before they do irreversible damage.

The Founding of Ghost Diving

Pascal van Erp has a commanding grasp on the issue of abandoned fishing gear. As the founder of Ghost Diving. Pascal’s passion has built a formidable and forward-thinking movement. Speaking to Pascal is a unique experience. He exudes a quiet confidence that only time and experience can build. In researching his work to prepare for his visit and subsequent presentations, it became quite apparent that Pascal is consistent in his message. The message is that Ghost Diving breathes new life into abandoned nets that can be recycled or upcycled. To reuse and upcycle the nets means to actively contribute to the health of the planet for today and more importantly, future generations.

Next, Pascal emphasizes Ghost Diving is dangerous. He explains that the dangers are not always apparent. Instead, they lurk in the shadows cast by ghost nets. Team dynamics are not only critical but a matter of life and death. Pascal frequently mentions the significance of trust. The ability to trust teammates to maintain composure in the face of adversity. Trusting that if something goes wrong, they can and will continue to problem solve. Trusting that they can and will save your life. The team must always perform at the highest levels. It is critical that the dive is executed according to plan and that the procedure is applied with absolute fidelity. The nets do not discriminate between human life and marine life. They are not forgiving. A diver can meet an untimely fate in the grasp of a ghost net.

Ghost Diving USA provides a unique and exciting opportunity by planting its roots here. With support from Zen Dive Co., ghost divers will have access to equipment, standard gasses and service that will meet all their needs while ensuring the quality and reliability of these resources. While funding issues had previously plagued Ghost Fishing, the Ghost Diving partnership with Healthy Seas along with other community sponsors helps to ensure the security of the critical funding that makes these projects possible.

Launching Ghost Diving USA

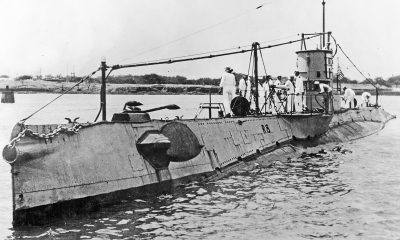

Zen Dive Co. hosted a launch event for Ghost Diving USA on Thursday, April 28. The energy in the building was electric. Everyone was thrilled to network, build community, and work towards supporting Ghost Diving USA in any possible way. Karim opened the evening by describing the net diving mission that the ghost divers had gone on earlier in the day. He explained in detail that the Moody, a Wickes class destroyer, sits at approximately 45m/150 ft. Conditions at sea were challenging. Spring is a rough season in Southern California. Variable winds cause large swells, and upwellings bring up life giving nutrients. Unfortunately, both phenomena significantly reduce visibility. This dive was no exception. Karim described a thick green cloud in the shallower depths cutting visibility to 4.5–6 m/15–20 ft. This green cloud blocked out all ambient light as the ghost divers descended, and then cutting the nets only made visibility worse. Essentially, there was no ambient light, and visibility quickly became next to zero. The ghost divers were forced to rely upon the light they brought with them. Despite the challenges, the net clean-up was successful, but the work is far from done. The ghost divers will have to return to remove more net.

Pascal made a brief presentation about the problem of ghost nets. It was incredible to experience a room full of people feeling compelled to act, and everyone looking for the way they could best support the mission. Veronika Mikos of Healthy Seas helped to drive the point home when she explained that through partnerships with organizations such as Bracenet and Aquafil, the recycling and upcycling of nets can help to significantly reduce carbon emissions. Additionally, as the ability to recycle nets and the products made from nets grows, they become sustainable and renewable. The yarn made from the nets can be processed infinitely and never loses quality.

The most precious resource to any of these projects is manpower. Volunteers. People willing to train hard, think of the many versus the one and ultimately focus on safety. A ghost diver is a technical diver that has successfully completed a series of training workshops that help to best prepare them for what they will experience on a net retrieval dive. The workshops also serve to build team cohesion. Pascal and Karim both explain that the need to work with technical divers is not to be exclusionary. Ghost divers need to be able to handle any situation that may arise at any moment. Technical divers are trained to do exactly that.

For recreational divers and non-divers alike, there is a place for everyone. Ghost divers cannot do what they do without support. Jim shared with me that his son, middle-school-aged at the time, used to volunteer as surface support. He and a friend would help to bring nets onto the boat and then search through them meticulously for any trapped marine life that could be released back into the ocean. Not only did his son help to raise awareness through multiple award-winning science projects, but he also became a diver crediting his experience helping with ghost nets. The Hamzas and Norbert hope to grow Ghost Diving USA to include recreational limit projects that allow for the training and participation of recreational divers.

Ghost Diving USA is hitting the ground running. If you are looking for a way to get involved, a great place to start is to follow them on their social media pages. They are on Facebook and Instagram as Ghost Diving USA or @GhostDivingUSA. If you would like to inquire about the application process, you can reach the USA chapter via email at [email protected].

You can also act right now. Learn about what abandoned fishing gear does to our oceans and talk to others about it. Through raising awareness, you can help remind people that while the surface of the ocean is beautiful, it is what is below the surface that desperately needs our help.

Dive Deeper

| Ghost Diving International: | https://ghostdiving.org |

| Aquafil: | https://www.aquafil.com |

| Bracenet: | https://bracenet.net/en |

| Healthy Seas: | https://www.healthyseas.org |

| Alert Diver: | Ghost Fishing by Michael Menduno. The story of Heather Hamza and her team (2014). |

Katie McWilliams is an avid diver, spending every spare moment she can in the water. Currently completing her divemaster and training for her technical pass, she wants to not only further her education and ability to explore the ocean but help with the training of divers. Specifically, Katie wants to focus on spreading awareness of how we can help the health and conservation of the oceans and marine life. Outside of diving, Katie works in moderate/severe special education. She enjoys reading, exercise, off-roading, camping and spending time with her husband, family and friends.