Community

GUE v. DIR: Towards A New and Unique Future (2004)

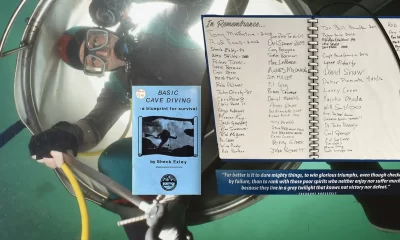

Here in this 2004 white paper, Jablonski presents the rationale, controversy, and evolution of the Doing It Right (DIR) system, discusses the rise of alternative DIR groups and how they differ from GUE, and charts out a new direction for the organization, all of which makes for fascinating reading for diving history buffs.

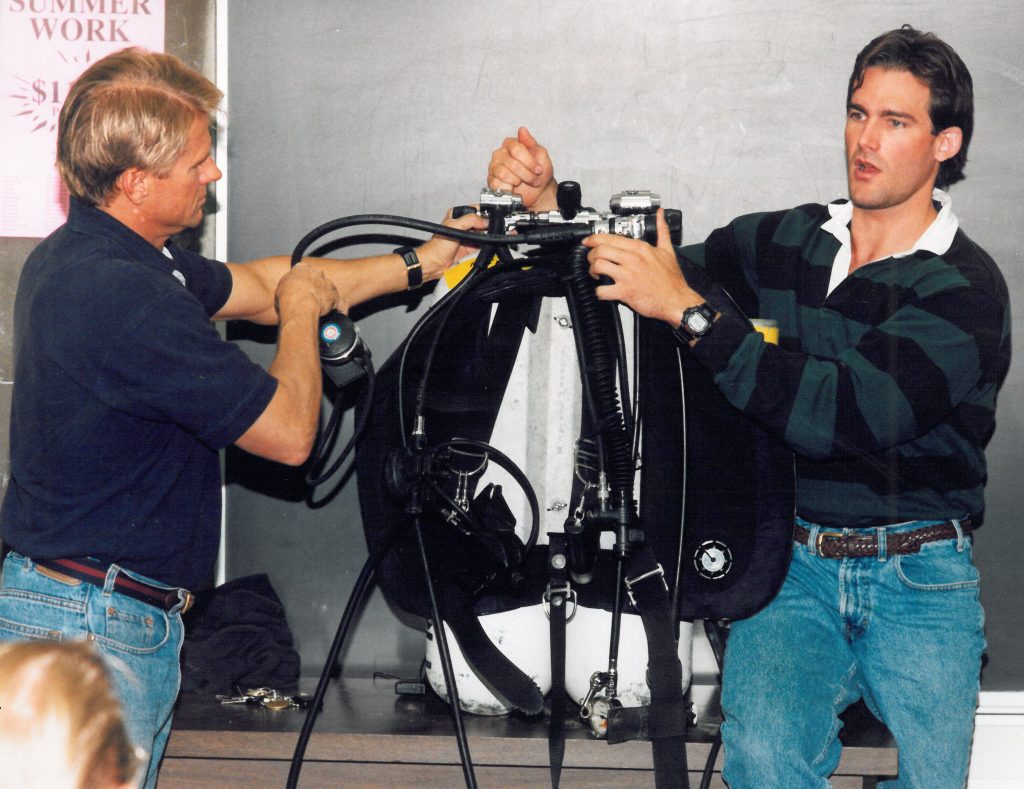

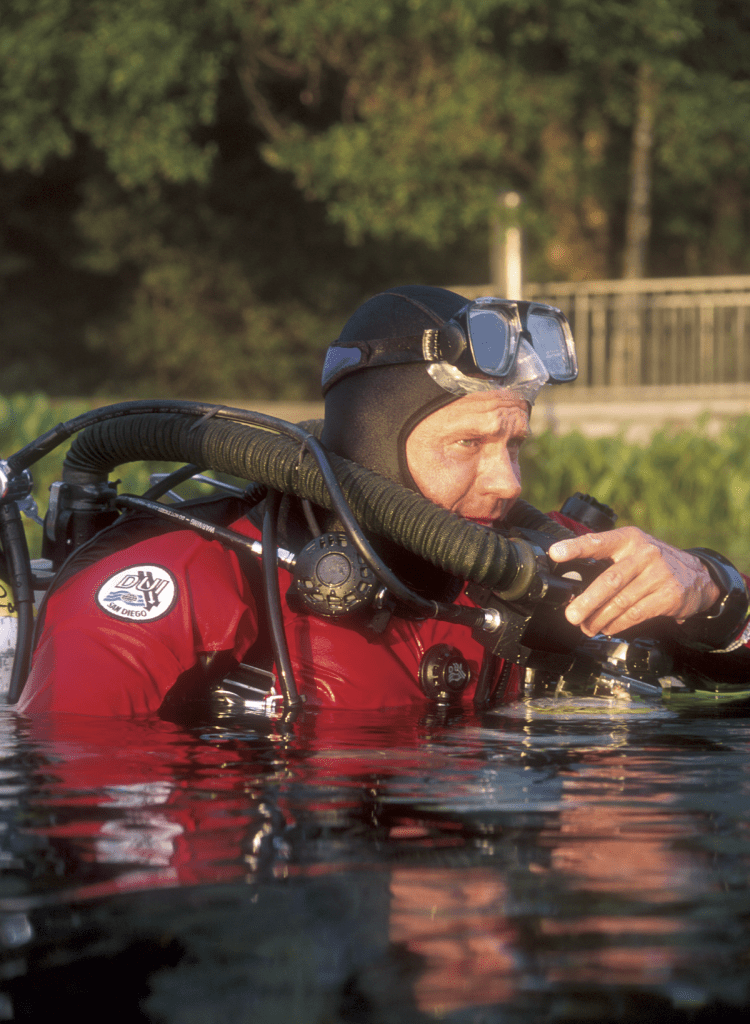

by Jarrod Jablonski, Preface by Michael Menduno. Images courtesy of GUE archives.

Preface

Standardization of equipment, gases and dive protocols are accepted and viewed as the norm in military and commercial diving. However, the idea of creating standards for sport diving teams in order to improve their safety and performance was, to say at the least, controversial in the 1990s when technical diving was just emerging. But that’s exactly what George Irvine, then the director of the Woodville Karst Plain Project (WKPP), and training director Jarrod Jablonski, did with the development of their groundbreaking “Doing It Right” (DIR) system of diving, which evolved from the earlier “Hogarthian” approach to cave diving developed by WKPP co-founder Bill ‘Hogarth” Main.

There’s little doubt that the DIR system garnered even more controversy as a result of Irvine’s pugnacious “my-way-or-the-highway” online persona, which arguably detracted from DIR’s importance. Jablonski went on to establish Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) in 1998, with the DIR system at its core. In fact, GUE’s membership magazine “QUEST” was originally named dirQUEST.

By 2004, Jablonski and Irvine’s system inspired the rise of a number of DIR groups around the world, each unaffiliated with GUE, and each with its own focus and nuance. This created some confusion and additional controversy surrounding what constituted GUE standards in comparison to other DIR groups. As a result, Jablonski authored an article titled, “Toward A New and Unique Future,” in the Summer 2004 issue of dirQUEST, which is reprinted below. Following that issue, the “dir” was dropped from the title of magazine, which was renamed “QUEST.”

In his treatise, Jablonski recounts in some detail the need, evolution, and clarification of GUE’s DIR standards, as well as discussing the rise of alternative DIR groups, the confusion that it caused, and the decision to take GUE in a new unique direction. His thesis makes for fascinating reading for diving history buffs like me.

In addition, he made several notable points which struck me as I read it. First, Jablonski pointed out that DIR was misunderstood from the beginning. Specifically, that it was NOT an indictment of non-DIR equipment configuration or practices, but rather an effort to promote uniformity among dive teams. There is more than one way to “do things right.” The key is to decide on a standard and stick with it.

Second, Jablonski concluded that DIR was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition of being GUE. In other words, GUE was bigger than DIR and encompassed a wider set of standards and practices. Those included the practice of “civility,” which was likely added in response to Irvine’s actions at the WKPP.

Interestingly, when viewed today, GUE’s standards have clearly demonstrated their robustness. In fact, one could argue that many of GUE’s standards, such as a pre-dive checklist, streamlined equipment, nitrox vs air, cylinder marking and gas switching protocols, as well as more conservative gas parameters—OK, not everyone has bought into helium beyond 100 ft/30m, yet—have been extremely successful in that they have largely been adopted by the technical diving community. Here’s what Jarrod Jablonski had to say back in 2004.

The article makes for fascinating reading for diving history buffs like me.

Toward A New and Unique Future

by Jarrod Jablonski, GUE Founder and President

The history of underwater exploration is filled with striking personalities and noteworthy actions. However, underwater exploration took on a new form with the emergence of scuba diving. Initially driven by commercial and military interests, underwater exploration using scuba grew to include sport divers, who embraced underwater exploration as their life’s passion and who sought to develop the best tools possible to complement their exploration needs. While the sport was in its infancy, and choices were limited, these divers did not vary greatly in terms of their equipment and configuration.Furthermore, given that training options at the time were also limited, these divers also shared very similar techniques.

As more people took up scuba diving, however, variation in equipment, training, and equipment configuration grew. With ever-growing numbers of people finding pleasure in open water, no decompression diving, a collective identity emerged reflecting the interests of recreational diving participants. An entire industry would soon follow to serve these interests. Concurrently, another identity would take shape, one tied to a group of divers, some coming from within recreational diving, some from without. These divers pushed the limits of recreational diving, exploring increasingly more demanding environments; e.g. caves, deep wrecks and ice. Over time, these two groups would diverge and each would follow its own trajectory. The somewhat vague (in part arbitrary) categories of “technical” and “recreational” diving can be used to describe these two trajectories.

Given the different orientations of recreational and technical divers, it should come as no surprise that different training practices, equipment choices, and configurations would emerge to answer to the wants of each. The evolving idea of what it meant to be “recreational” led to some divergence regarding what one needed to know to remain safe during dives of minimal difficulty. As a result, dive training tended to become shorter, with minimal treatment of topics such as gas planning, breathing gas concerns, decompression, and crisis management. Likewise, this shift led to greater variation with respect to equipment choices and to how this equipment would be configured.

However, the needs of technical diving generally required greater knowledge of these areas, more precision, more attention to detail, refined skills, practiced crisis management, a sound configuration, and well-crafted and well-maintained equipment. Conventions foreign to the recreational diving community, such as the “thirds rule,” the use of a long hose and a redundant regulator, emerged specifically to address the needs of the technical diver. However, in time, it became apparent that the more precision and proficiency that was required to pursue exploration-level technical diving, the more the need for a unified system. That’s because it was impractical, if not impossible, to operate efficiently as a team if individuals were not functioning under a common set of constraints.

Regardless of environment, there is substantial variation among divers with respect to both the value they place on efficiency and how intensely they seek to extend the limits of their diving practice. I would argue that the position that divers take on issues of efficiency is largely tied to the nature of their diving. For instance, it is clear why early divers did not consider standardization an urgent need. That’s because their diving was less aggressive and thus less likely to demand a high level of efficiency.

However, as diving became more aggressive and more complex, the benefits of precision and efficiency become progressively more obvious; individuals undertaking such dives quickly realize the benefit of standardizing nearly all aspects of their diving to make it more efficient. So, when evaluating different equipment configurations—from those used in the early days of underwater exploration, to those representing “Hogarthian” ideas (discussed below), to the evolving principles of “Doing It Right”—it is useful to keep in mind the importance of efficiency in dealing with complexity.

As a greater number of divers (both recreational and technical) discover the value of efficiency as a means of improving the quality of their diving, standardization in training and equipment, seems the likely future of the practice of diving. The public first became aware of the movement toward standardization and of its value, when the Hogarthian diving system became popular. This scheme was composed of a rough set of ideas and equipment recommendations that served as useful standards for measuring desirable aspects of diving equipment configurations.

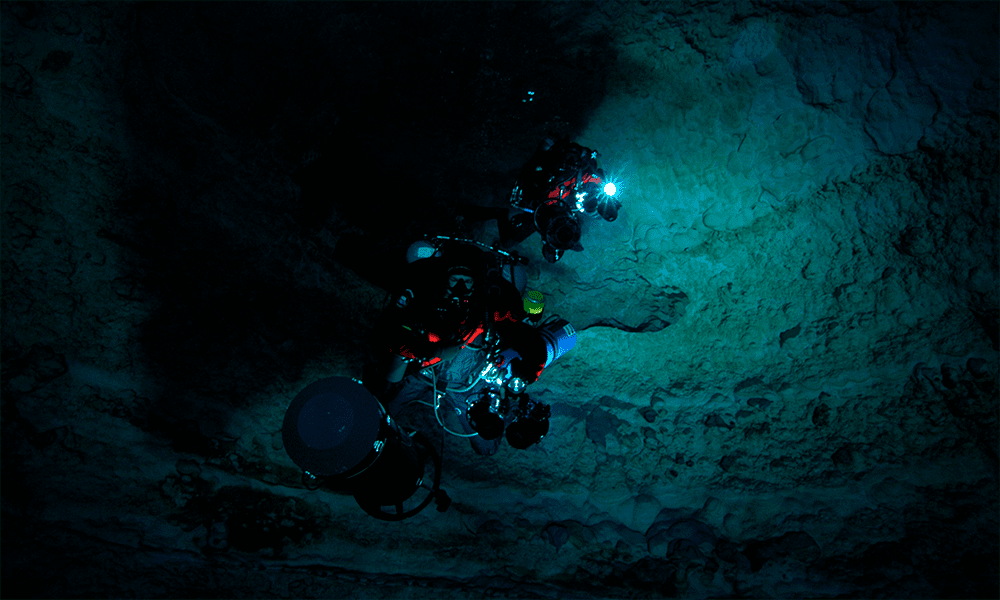

Cultivated by a small collective of cave explorers, i.e., Bill Gavin, William “Hogarth” Main, Lamar English, George Irvine, and myself, the idea behind this “system” was that there were preferred methods of configuring equipment, and that these methods had a profound effect upon diving efficiency. Bill Main invested considerable time seeking the most streamlined configuration possible, which resulted in his middle name being chosen to represent the overall system.

Though useful, the Hogarthian system did not require a specific piece of equipment or a particular configuration. Therefore, it did not provide divers with an objective diving standard that would ensure efficiency in the water and was thus limited in its utility. However, by promoting the idea that a careful selection of equipment and configuration could substantially impact the success of a dive, Hogarthianism introduced a dynamic new paradigm to divers and encouraged them to seek improvement through minimalism and streamlining. Armed with this new perspective, many divers (myself and the above explorers included) sought to assemble the most efficient equipment configuration possible, often sharing our findings with the public at large.

Rather than provide divers with an objective standard to assemble their configuration, Hogarthianism offered a loosely-knitted set of ideas or philosophy that, in the interest of diver efficiency, promoted an ethos of careful gear selection. However, the lack of an objective standard did not permit divers to understand what exactly constitutes a Hogarthian diving configuration. Instead the “system” varied according to how different advocates of Hogarthian diving saw the links tying together equipment, streamlining, and efficiency.

This disparity of opinion, along with Hogarthianism’s singular emphasis on equipment (versus general diving practice) led to considerable confusion among the diving public (it was extremely difficult to standardize what, was largely subjective in nature). Eventually it became clear that both a more complete system and greater standardization were needed. To be as useful as possible, the components of the system would need to be objectively arrived at and standardized. George Irvine and I, having worked extensively with the Hogarthian system, and having written at length about it, worked toward this new paradigm. We named this new paradigm “Doing It Right” or DIR.

As the first holistic scuba diving system ever crafted, “Doing It Right” began to gain significant popularity in the mid-1990s; a key component of its success was the detail and care that guided its growth. By adhering firmly to standardization, DIR initially faced opposition from diving quarters that saw the loss of “personal preference” as a notable sacrifice. Even so, with the gradual recognition that it is impossible for a team of divers to be efficient in the water without notable uniformity in equipment, training and configuration, opposition began to erode and continues to erode to this day. That’s because divers have begun to realize that there is a significant penalty in terms of wasted energy and effort for stubbornly seeking to maintain an individual “style.” Why reinvent the wheel alone when there is a proven system that ensures safety, efficiency, and success in the water?

Because DIR’s insistence on standardization is frequently misunderstood, it sometimes becomes a source of tension among divers. That’s because some see the insistence on uniformity as an indictment of practices that do not abide by DIR principles. However, there is nothing essentially hostile or critical about DIR; in its most basic form, it is ultimately pragmatic, promoting the concept of uniformity within and among teams of divers.

Because DIR’s insistence on standardization is frequently misunderstood, it sometimes becomes a source of tension among divers. That’s because some see the insistence on uniformity as an indictment of practices that do not abide by DIR principles. However, there is nothing essentially hostile or critical about DIR; in its most basic form, it is ultimately pragmatic, promoting the concept of uniformity within and among teams of divers.

To be fair, there is a certain degree of legitimate tension generated by imprudent advocates of DIR. Having personally benefited from the system, they take it upon themselves to become almost evangelical in their promotion of what they understand to be its tenets. Nevertheless, this is not an intrinsic weakness of DIR; all successful movements have their zealots.

By crafting a set of objective standards meant to regulate diving practice, DIR triggered a paradigm shift in diving, one that will forever modify the way that divers evaluate their diving. It is now part of our ethos to believe that divers acting cohesively and with shared purpose are more efficient. Nonetheless, considering standardization in isolation is unfair to the system’s holistic approach.

DIR Principles

As a well-defined, standardized system, DIR was designed to maximize efficiency across multiple environments in order to promote safety and fun. Among its key principles are:

Unified Team

Central to the DIR diving system is the concept of a unified team. This system pairs divers of similar capacity within an environment that they are properly prepared for. Teams of individually capable divers produce a level of safety and efficiency beyond what is capable while diving independently. Few things are as rewarding as diving within a group that maintains a similar degree of care and focus. Any diving activity where the concept of a team is marginalized will always fail to maximize its potential with respect to fun and safety.

Preparation

For DIR, preparation for diving involves five primary components. These are: pre-dive preparation, mental focus, physical fitness, diving experience, and dive planning. Divers who try to circumvent any of these areas are not adequately prepared for the dive and stand a good chance of experiencing reduced comfort, a missed dive opportunity, or even a dangerous situation. With ill effects, far too many divers assume that dive preparation begins the day or even hours before the dive.

Streamlined Equipment

The elements comprising a standard DIR equipment configuration have been endlessly discussed and are now well known. For those seeking more information on this subject, please refer to my book, “Doing it Right: The Fundamentals of Better Diving.”

In short, the DIR configuration was designed to work in a majority of situations and to ensure safety and promote a diver’s efforts, not undermine them. Streamlined and minimalist in nature, the DIR configuration was designed to maximize divers’ efficiency while minimizing their risk. Items should not hang free or protrude from divers’ bodies, increase drag or cause entanglements.

Balanced Rig

The DIR rig is a carefully weighted rig; one that ensures that while divers are not over-weighted, they are able to hold a decompression stop in the face of a catastrophic gas loss. This requires a careful assessment of the component parts of one’s configuration, and how these each impact statically and dynamically, on the buoyancy characteristics of the configuration as a whole.

Cylinder Labeling

DIR embraces the uniform practice of marking cylinders with the Maximum Operating Depth (MOD) in a clear and easily identifiable manner, and utilizing only this data to identify bottles. This practice prevents divers from becoming accustomed to unreliable identification procedures.

Standard Gases

DIR promotes reliance on standard gas mixes for all phases of diving. “Standard gases” help to insulate divers from the risks of inappropriate gas ratios, provide a common platform for cylinder marking and gas mixing, ensure team symmetry, and vastly simplify decompression logistics.

Conservative Gas Parameters

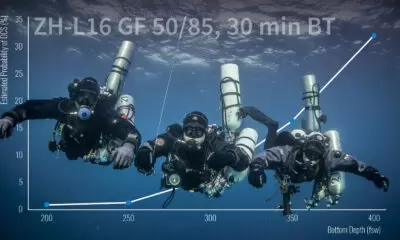

DIR promotes conservative gas parameters for all phases of diving. Among these are: Equivalent Narcotic Depths (END) of less than 100 ft/30 m, the partial pressure of oxygen (P02) during the working phase of the dive of 1.4 ATA or less, and P02s of 1.6 ATA or less for decompression. To offset the toxic effects of oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide, DIR recommends the liberal use of helium together with the conservative use of oxygen.

GUE Diving

To a careful reader, a casual review of diving history will reveal a movement toward greater standardization. DIR’s place in history is assured, given its role in introducing a new paradigm to the diving public, one where standardization provides divers with the key to efficiency, safety, enjoyment and success. Though there is still variation among divers, in time, the desire for proficiency will force them to migrate toward a known paradigm that through its insistence on standardization, ensures phenomenal success in both extreme diving projects and in recreational applications. For this reason, the trajectory that the history of diving will follow will speak volumes to the impacts of the DIR movement.

With all great movements, comes inevitable corruption and fragmentation. Today, DIR has spread to every corner of the globe, with self-appointed DIR groups emerging in dozens of different countries. Given their physical separation, their lack of centralized direction, their own specific agendas, beliefs, power struggles, and constraints, these satellite groups cannot help but to promote a version of DIR that is uniquely their own. Many of these “versions” of DIR bear little resemblance to the original, however well-intentioned and devoted to the founding principles of DIR these groups may be.

The unavoidable division of DIR is the result of many factors, ranging from breakdowns in channels of communication, to differing interpretations, to personal agendas, to private experiences, to power plays, to simple disagreements among proponents. As individuals and groups adopt DIR they will often make choices very different from those that I and other founders of DIR would have made. As a result, it is necessary for us to recognize that DIR will be repurposed by those it has influenced in ways that serve their own interests. Nonetheless, in the end, I believe that these systems that adopt DIR can only benefit the future of the diving industry. Even so, I believe that to enhance the safety, fun and efficiency we sought to ensure when we first started to build DIR, it is necessary for us to ensure greater standardization across additional domains.

From the outset I believed that divers’ training, their equipment, their configuration, their knowledge, and their skill set should all contribute to greater safety and enjoyment in the water. That was the reason I founded GUE. The DIR system is at the core of GUE training. That is not surprising, given the extent to which my efforts helped to shape both DIR and GUE. However, with the passage of time, GUE has shaped its own identity, one that is not identical to that of DIR. And though being DIR is a necessary condition of being a GUE diver, it is not a sufficient condition; it is not enough.

There is more to being a GUE diver than being DIR. Among other things, it entails a standardized measure of competence (training), a commitment to civility, and also to non-smoking, aspects to which DIR in-itself does not speak.

There is more to being a GUE diver than being DIR. Among other things, it entails a standardized measure of competence (training), a commitment to civility, and also to non-smoking, aspects to which DIR in-itself does not speak. Over time, GUE vice-president and long-time DIR supporter Dr. Panos Alexakos and I came to see that there was really no way to reign in the growing number of interpretations by DIR advocates; it would be a waste of resources and energy to struggle with them over the correct interpretation of DIR. With this in mind, we have struck out on a new road, a distinctly GUE road that looks fondly upon DIR as the foundation that can empower the organization toward a new and unique future.

DIVE DEEPER

GUE.tv: DIR 2004 – Basics of “Doing It Right”

Jarrod Jablonski is an avid explorer, researcher, author, and instructor who teaches and dives in oceans and caves around the world. Trained as a geologist, Jarrod is the founder and president of GUE and CEO of Halcyon and Extreme Exposure while remaining active in conservation, exploration, and filming projects worldwide. His explorations regularly place him in the most remote locations in the world, including several world record excursions at 300 ft to cave penetrations in excess of 24,000 ft/7 km; these dives include bottom times of 12 hours with total immersions near 30 hours. Jarrod is also an author with dozens of publications, including three books and more forthcoming, as well as several awards for lifetime achievement, including the 2018 DAN-Rolex Diver of the Year, 2016 Eurotek and 2015 Golden Trident. He successfully completed his first Ironman in April 2019.