Community

Hal Watts: Plan Your Dive

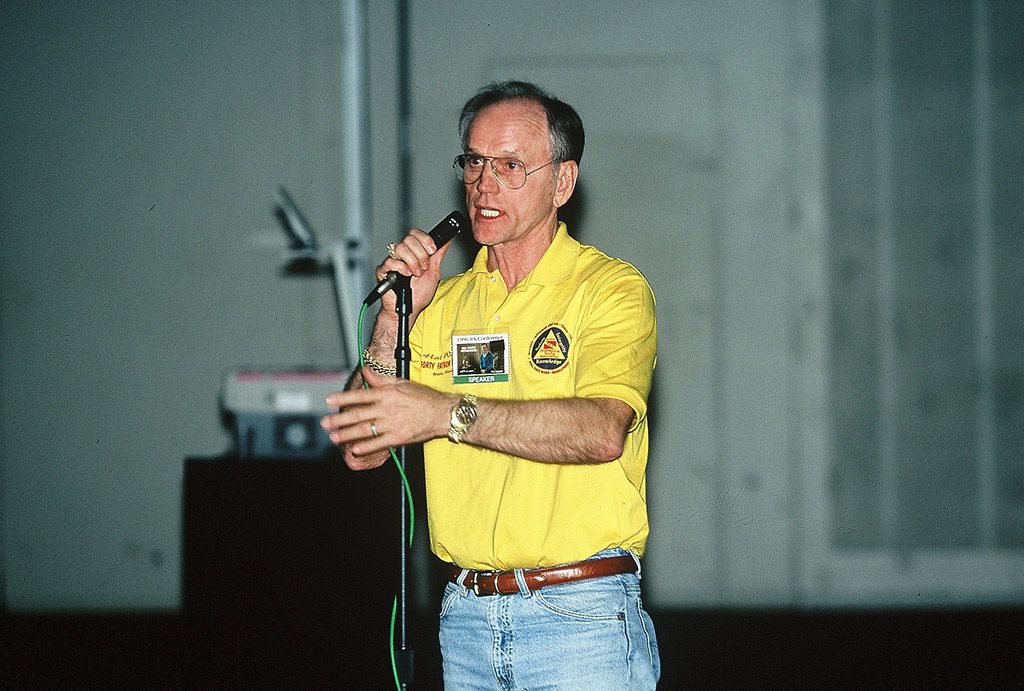

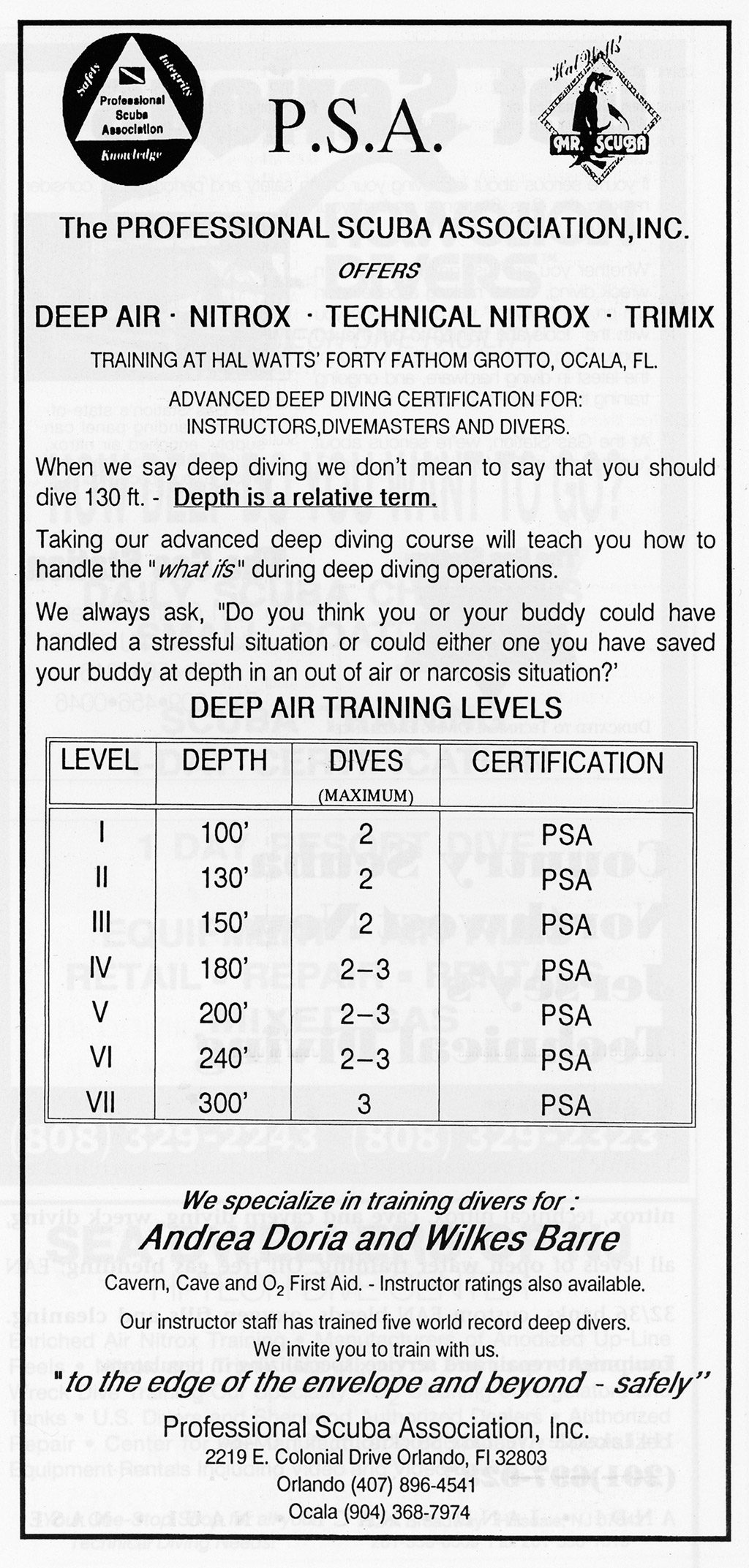

Known for his deep air diving exploits back in the day, 86-year-old Hal Watts, aka “Mr. Scuba,” is one of the pioneers of early scuba and credited with coining the motto, “Plan Your Dive. Dive Your Plan.” He founded the Professional Scuba Instructors Association International (PSAI) in 1962, which eventually embraced tech diving, but never relinquished its deep air “Narcosis Management” training. Italian explorer and instructor Andrea Murdock Alpini caught up with Watts and teased out a few stories from the training graybeard.

Interview by Andrea Murdock Alpini

English text by Vincenza Croce

“Plan your dive, dive your plan,” is a common refrain in diving, but it’s easy to forget the meaning of this phrase has changed over time.

The underwater explorers of the early days learned to plan their dives with watches, depth gauges, and US Navy tables. Back then, decompression tables were the Bible for divers—something miraculous, halfway between alchemy and physiology. Those trail-blazing divers defined what it meant to “plan” a dive.

But, at the time, the term “technical diving” did not exist; divers breathed air on the bottom as well as during decompression. Only after many years was oxygen added, followed by the famous jump into the hyperbaric chamber.

Later came new innovations after a few decades of experiments: hyperoxygenated binary mixtures, the NOAA tables, Heli-air (i.e. the addition of helium in tanks loaded with air), the change in the speed of ascent, new molecules to be studied, new physiological and narcotic effects, and their consequent impacts on humans and their psyches.

In a very short time, diving traditions underwent a metamorphosis. The spool and the coral tank became a proper reel, the ascent bin and the plastic bag disappeared in favor of the buoyancy control device (BCD), the surface marker buoy appeared—and then, even later on, wrists were adorned with underwater computers instead of decompression slates.

Divers later renewed and revolutionized a niche discipline, transforming it into a sporting phenomenon and a vocation. Faced with imminent change, there is often nothing that can be done when an anomalous wave arrives; you cannot stop its irresistible force with the wave of a hand. And thus was the American revolution of underwater technique, where the means of exploration—read mixed gas and scooters—have become the end.

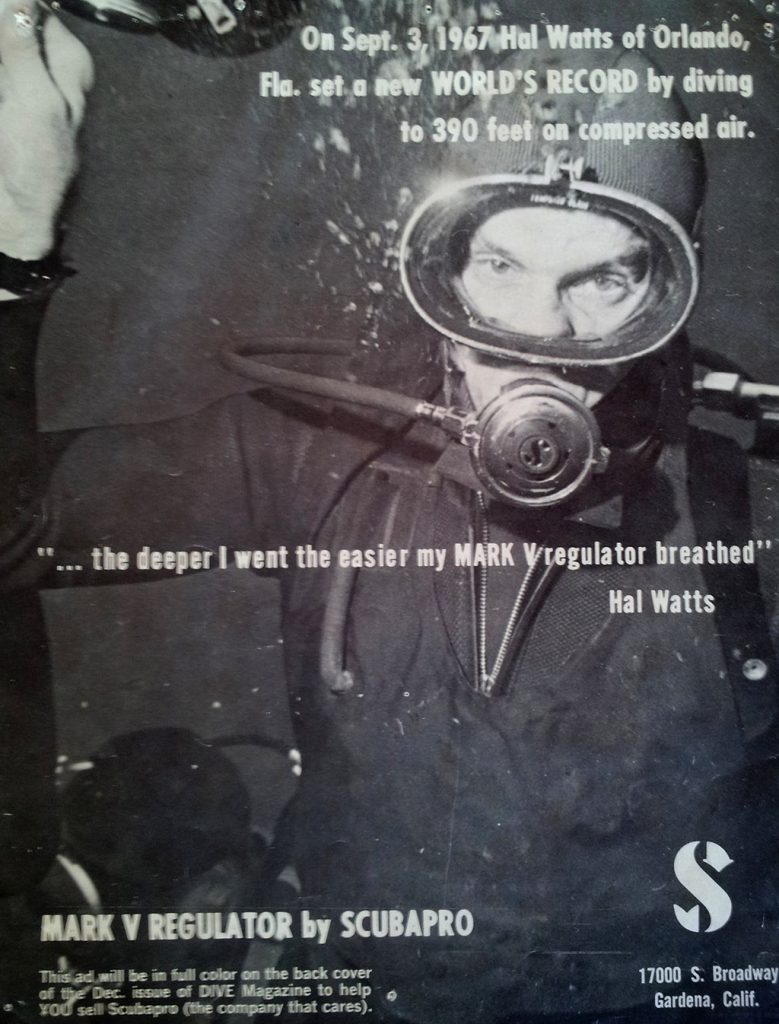

The self-proclaimed originator of the “plan your dive, dive your plan” motto was 86-year old Hal Watts, the founder of American didactic Professional Scuba Association International (PSAI) and a diving pioneer who once held the Guinness Book of World records for deep diving. Though the use of trimix grew in popularity, Hal continued to believe in deep air, in the ancient technique of coral fishermen. He supported wreck and cave diving—with decompressive mixtures and new configurations through PSAI; but, above all, he believed (and continues to believe) that deep air, if properly practiced, is a discipline with unique logistics, hidden dangers, and irresistible charms that can take you to a parallel world.

First of all, Hal, what was the dive that changed your way of seeing scuba diving? I mean, a dive that was like an epiphany, a dive which changed your point of view on a technical matter?

Hal Watts: Wow, you sure are really trying to test my old man memory. Now I’ll have to review some of my old logbook entries.

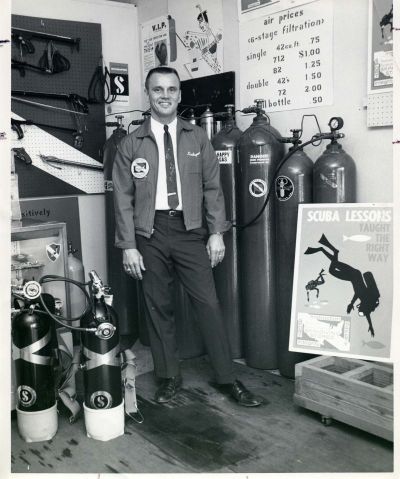

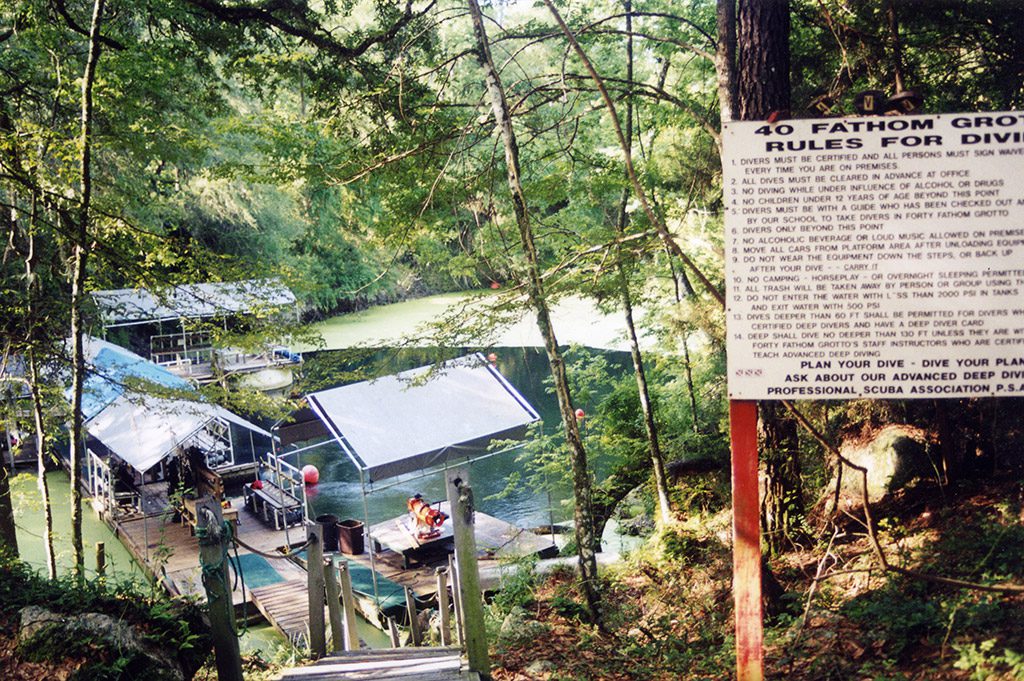

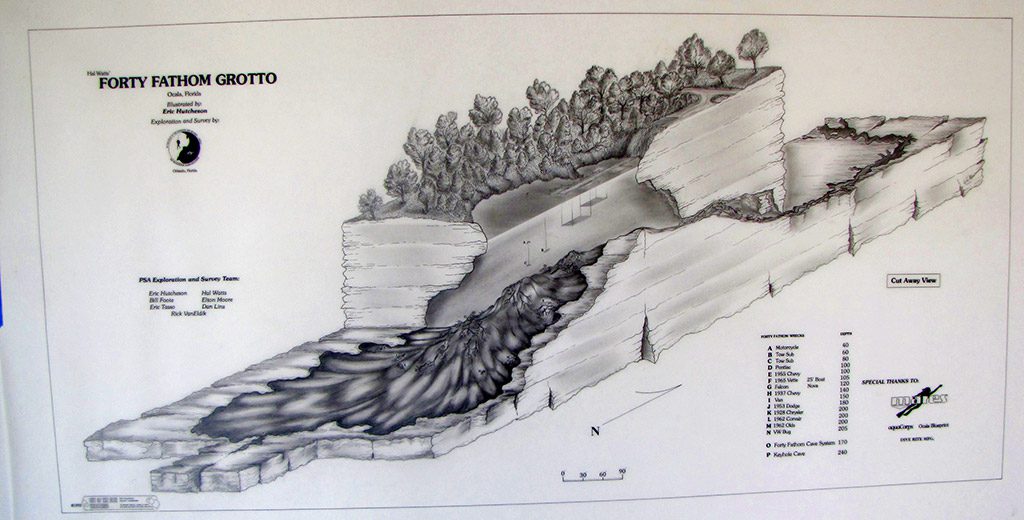

The first scuba dive that really got my attention as to just how serious and dangerous scuba diving can be was on December 2, 1962. I was diving with Bob Brown, co-owner of Florida State Skindiving School in Orlando, Florida. I was a member of a dive club in Orlando known as Orlando Sport Diving Club. Bob and I had heard of a sinkhole in Ocala known locally as Zuber Sink as well as Blue Sink. Years later, I later leased the property and renamed it as Hal Watts’s 40 Fathom Grotto, and I eventually purchased the Grotto in mid-1979.

We had never talked to anyone about the sinkhole; therefore, we had no idea about the visibility or the depth. Up to this point, I had constructed my favorite BCD, using a large white Clorox plastic jug, which we tied to our twin tank system. We put air into the BCD from our “Safe Second Stage” mouthpieces.

Bob and I tied our safety line to a tree on the bank of the sink and reviewed our dive plan. I am reminded of the motto I came up with, many moons ago—Plan your dive, dive your plan.

We all know that motto. I didn’t realize that it was you who coined it.

It was back in the 1960s when I was writing course manuals for NASDS [National Association of Scuba Diving Schools] and opened up my Mr. Scuba dive shop.

But back to the dive at Zuber. I’ve failed to mention the fact that neither of us had been doing any dives below 30 m/100 ft. We followed the cave line down slowly, not paying enough attention to our depth. Before we realized it, we had hit the bottom, stirred it up, and had no clear water.

Lucky for us, I kept the cave diving reel in my hand, and Bob kept his hand on the line. I couldn’t see; however, I could feel Bob’s hand, squeeze his fingers tight on the line, grab his thumb, and give it the “thumbs up” signal. I don’t know how we managed it, but we were both able to use our NASDS safe second stages and add air into the Clorox “BCDs.” We were actually fated to begin an uncontrolled, too-rapid ascent. All of a sudden, we hit an overhead wall, which stopped our ascent at a depth of 9 m/30 ft.

We looked at each other, and gave the OK hand signal. While decompressing, following the old Scubapro SOS mechanical computer, I started to pull up the loose line until the dive reel appeared. Wow, we sure had an awful lot of loose line floating around us. Were we extremely lucky? Of course, we were. Our problem was that we never planned our dive, and consequently, were unable to dive a plan.

After that dive, I worked with Scuba Pro and Sportsways to create the “Octopus,” or “safe second.” A while later, the octopus appeared for the first time in Scuba Pro catalogs. I was also the first to add a pressure gauge along with the Octopus.

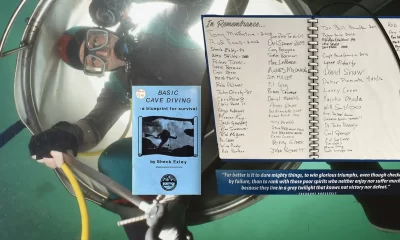

Ah yes, the “Safe Second.” That’s what NASDS called backup second stages, right? Sheck Exley (1949-1994), the legendary cave explorer with whom you were friends, was also credited with fitting a redundant second stage reg with a necklace. I want to ask you more about Exley, but first, I want to know: What are the best wrecks you ever dived?

This is really very hard to answer. I’ll have to list four, in the order that I dived them: the USS Monitor, Andrea Doria, Japanese wrecks located in Truk Lagoon, and the Lusitania in Ireland.

The most important would have to be the USS Monitor, a submarine used during the Civil War. A group of well-known USA divers applied to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for a permit to dive the Monitor, as she was located in protected waters. In addition to myself, the group consisted of: Gary Gentile, attorney Peter Hess, and several other well-known expert divers. At first, NOAA refused. Then, Peter Hess filed proper papers asking that we get the NOAA permit. To that end, we presented my Deep Air training material to the concerned NOAA group. I appeared as an expert witness and provided NOAA staff and their legal representatives with my internationally accepted training material and my record of training several world record deep air divers. Our deep air training has been accepted worldwide with zero diving deaths. After that, we received the permit.

Other than the Monitor, my favorite deep wreck dive would be the Lusitania, which is a very personal and proud story for me. The main reason is because venture capitalist Gregg Bemis owned the diving rights to the Lucey at the time. Gregg had contacted me requesting that I train him on PSAI Narcosis Management Level V, on air—which is 73 m/240 ft—and then train him on trimix so he and I could dive to 91 m/300 ft on the Lusitania lying off the coast of Ireland.

When word got out that I had enrolled Gregg in my Narcosis Management Course, a well-known international course director (a personal friend of mine) called and told me, “Hal, do not teach Gregg deep diving.”

He told me that he had been training Gregg at his facility, and that he was a “train wreck.” “He is from a very well-off family in Texas, and if you cause him any injuries, you will be sued and put out of business,” my friend said. Well, guess what? Gregg completed the 240 Level V Deep Air course, then our PSAI Trimix course. My wife, Jan Watts, Gregg, and I went to Ireland to dive the Lusitania. He and I made an awesome 91 m/300 ft trimix dive to the deck.

Diving on the Andrea Doria with Tom Mount, Peter Hess, and several great wreck divers was also an awesome dive. Last but not least was a great trip to Truk to dive on some of the Japanese wrecks.

Please tell us about Sheck. What was your relationship with him like?

Sheck and I became friends and made several dives together, and one of my favorites happened when Sheck, his Mary Ellen, my wife Jan, and I were diving at 40 Fathoms. Sheck wanted to practice gas switches during descents. Sheck was practicing, getting ready for a planned very deep dive (I think in Mexico with Jim Bowden). The four of us swam to the east side of The Grotto, slowly following the wall during our controlled descent, watching Sheck practice gas switching.

After reaching our planned depth of 73 m/240 ft, we began our controlled ascent up to our first planned deco stop. During our last deco stop on our 4.5 m/15 ft platforms, I noticed that Sheck had a funny look on his face and was messing with his drysuit between his legs. I remembered then that he had told me that he had an attachment installed in the drysuit that would allow him to pee underwater. He was clearly in a bit of discomfort and Mary Ellen, Jan and I just floated nearby and watched.

I’ve heard that Sheck later used diapers, or just cut it loose in one of his old neoprene drysuits on his big dives, so evidently he didn’t get that early p-valve to work. What about your friendship and job collaboration with Gary Taylor, your brother-in-arms and a co-owner of PSAI?

Andrea, get comfortable, since this question will take some time to properly answer.

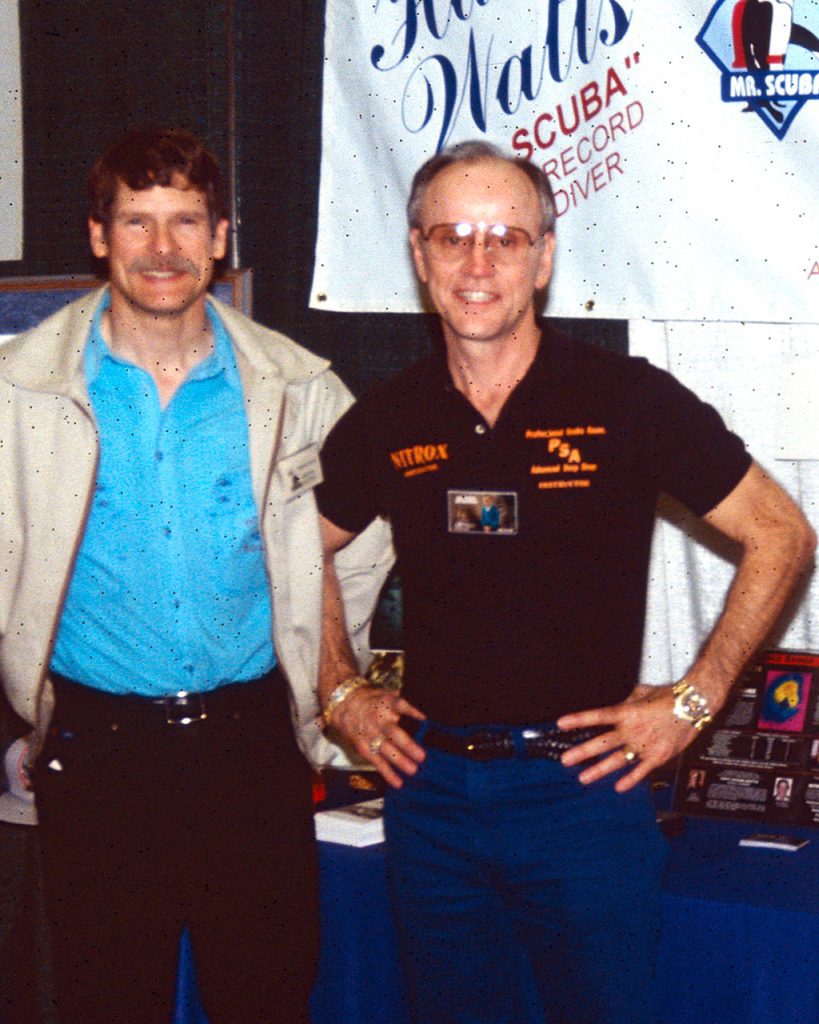

I first met Gary in Miami, which is where we became friends when I was staying in his home and taking Tom Mount’s nitrox course. I have a photo of Tom, Gary, and me gas blending on the floor of Tom’s garage. During the course, Tom was still using his worn-out hand written paper flip charts as his notes.

Gary was impressed with my deep air program and offered to put together an updated slideshow presentation for me to teach with. PSAI still uses an updated version of this system to date. Gary stayed with Tom until Tom thought he had sold IANTD [International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers] to another individual. After that sale came about, Gary contacted me wanting to get more involved with PSAI. Being smarter than folks thought I was, I jumped at the chance to have Gary on the PSAI Team. Tom’s deal fell through, but Gary was totally involved with PSAI, and now is a partner and president of our agency. Thanks to Gary and Tom.

Many, many years ago I was still taking some type of classes—I think regarding mixed gasses, maybe with Rebreathers—at Tom’s house. In fact, I was one of Tom’s instructors who did the final proofreading of one of Kevin Gurr’s manuals. Too far back to recall much about this mixed gas stuff—remember my reputation for being a deep air diver.

Speaking of the people with whom you’ve dived, was the aim of The Forty Fathom Scubapros Club?

Before I invested in a sinkhole in the Ocala, Florida, area—which was locally referred to as Blue Sink or Zuber Sink, and is now referred to as 40 Fathom Grotto—several diving buddies whom I had dived with and trained for extreme deep air diving—as well as cave exploring—got together and planned to dive The Grotto at least one Friday night per month. Within a short period of time, several other buddies joined our group, which eventually became known as The 40 Fathom Scubapro’s dive club. Each diver had to meet my requirements of training.

Eventually, our group set specific personal requirements—being a good person, supporting our club safety rules, and making at least one 40 Fathom Grotto dive per month. We set a limit of 14 or 15 members. Three 40 Fathom members eventually set World Records for deep air: I was one, A. J. Muns, and Herb Johnson set ocean records, and later I set the air depth record for cave diving. Naturally, as time passed and we got older, our membership got smaller. It is notable that none of our club members have died during any scuba dive.

Finally, what led you to create the iconic motto, “Plan Your Dive. Dive Your Plan?”

I used to be a private pilot, and we used to say, “Plan your flight, fly your plan.” This was back in probably 1961 when I had just started diving and there were so many instances where all the other divers would get in the water without saying anything. I’ve seen so many incidents and fatalities that could have been avoided through proper planning.

Dive Deeper

ScubaGuru: LXD 029 : Hal Watts – Record Deep Diver & Technical Diving Pioneer

Netdoc: Netdoc chats with Mr Scuba, Hal Watts

InDEPTH: The First Helium-based Mix Dives Conducted by Pre-Tech Explorers (1967-1988) by Chris Werner

Alert Diver.Eu: Rapture of the Tech: Depth, Narcosis and Training Agencies

Professional Scuba Association International: PSAI History

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and PSAI technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of PHY Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. He published his first book, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti (2018) and IMMERSIONI SELVAGGE, the new one is on the way, out on fall 2022.