Community

Getting to the Bottom of the HMS Regent Mystery

Italian shipwreck explorer Fabio Bisciotti and his team have reportedly solved the mystery of the HMS Regent, one of four Rainbow-class submarines built for the Royal Navy, that was lost at sea during WWII and discovered 50 years later near the Puglia region of Italy. Au contraire! Bisciotti et al, have now identified the wreck as that of the Italian sub Giovanni Bausan, and subsequently located what appears to be the remains of the Regent near the port of Brindisi. InDEPTH managing editor Ashley Stewart reached out to Biscotti to get the deets.

By Ashley Stewart. Images courtesy of Fabio Bisciotti and Michele Favaron.

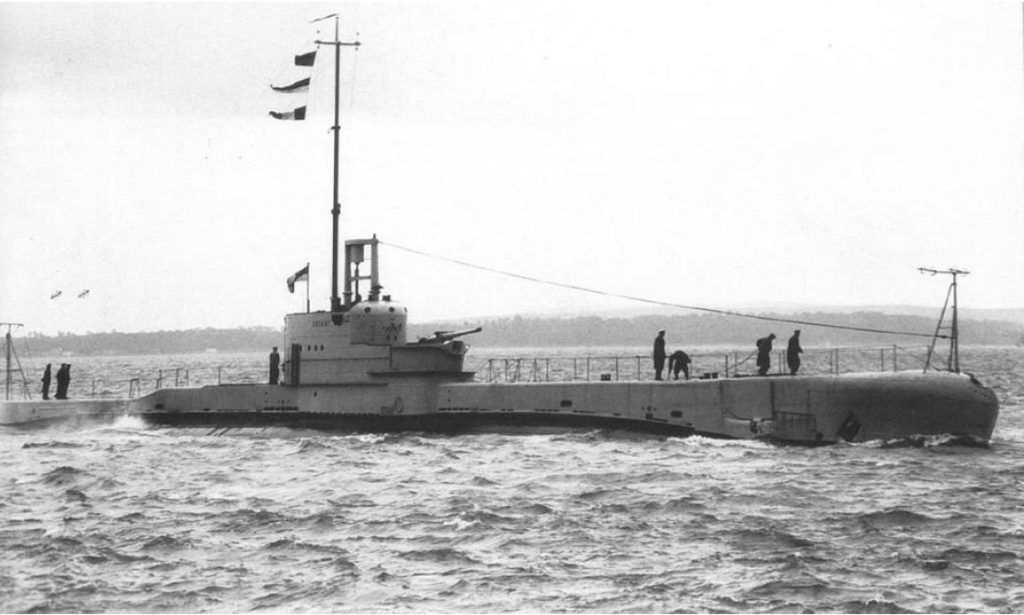

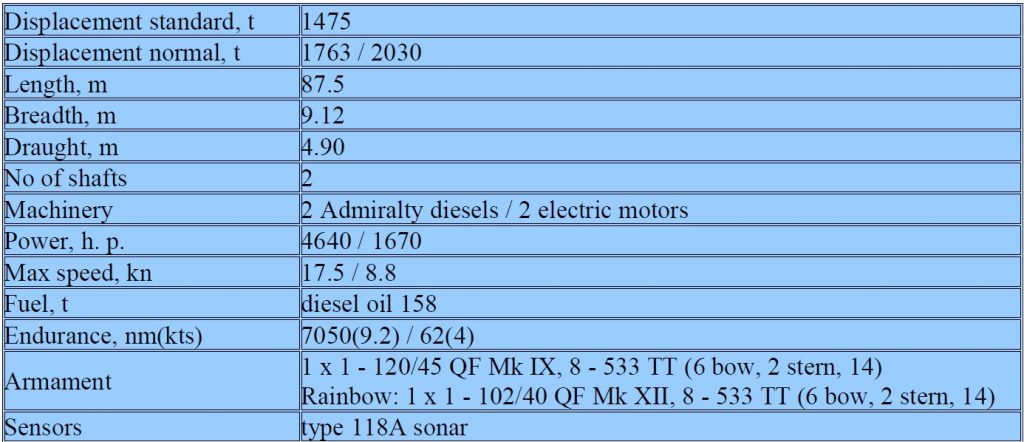

The HMS Regent, one of four Rainbow-class submarines built for the Royal Navy, patrolled during World War II until she was lost at sea sometime in April 1943.

There would be no news of the submarine for more than 50 years, until a research team proclaimed to have found the wreck in the Apulia region of Italy. But the Regent was lost once more when the site was declared by another team, including Italian explorer Fabio Giuseppe Bisciotti, to be instead a former Italian submarine once called the Giovanni Bausan.

Now, Bisciotti believes his team has solved the mystery of the HMS Regent once and for all, discovering a wreck with similar characteristics near the port of Brindisi. InDEPTH spoke with Bisciotti about the discovery and why he believes he’s found the wreck of the HMS Regent. Bisciotti previously spoke to InDEPTH about finding a sunken German WWII aircraft in the South Adriatic Sea. Edited for length and clarity.

Bisciotti’s report: English, Italian (Original)

How did your search for the HMS Regent begin?

We know during the war many submarines from the United Kingdom were lost here in the Adriatic Sea. From some combat diaries about some skirmishes in this area, we know we have various wrecks including submarines and one of them is the HMS Regent. We started this research with a unique objective to know the truth about this wreck.

Many years ago, a research team believed they found the HMS Regent. But after our research, we discovered it was an error. The previous research team believed they found the Regent in an area much farther north in the Apulia region in the Barleta area. The wreck in this area is not the HMS Regent but a former Italian submarine called the Giovanni Bausan. It was used after the arrival of allies in the south of Italy as an oil depot, renamed GR 251, without a conning tower or propellers, transformed into a big warehouse. We have documents from the National Archives in London that show American allies sunk this wreck in the same region.

How did you discover the wreck you now believe is the Regent?

We started developing some research and arrived in the real area where we believed the Regent was lost, quite south near the port of Brindisi. Thanks to the fisherman of the area and old witnesses, we discovered a story.

Here, in the late afternoon on the 18th of April of 1943 — the exact day when the Regent was lost — in front of the seashore, it was heard a very big explosion. The next day, some oil and fuel formed four or five miles out in the open sea where it was believed a submarine hit a mine. By the reports of the Italian Coast Guard of that time, the bodies of four sailors were found in the days after the accident. The first was found in an area nearby Brindisi. A second body was found in the Missipezza area south or Brindisi, and two other bodies were found in the Otranto and Castro Marina areas. The bodies were found between eight and 25 days after the accident. You can imagine the condition of these poor guys, but it is believed one was a non-commissioned officer and the other three were simple sailors. They were surely submariners due to their uniforms, which were blue as British submariners.

After much time, we narrowed down the area thanks to the local fisherman, and found a very object in the water around 80 meters down. The area is quite dangerous due to quite strong drift, and the direction of the wind from the area would create the correct route to where the bodies were found.

Why do you believe this wreck is, in fact, the HMS Regent?

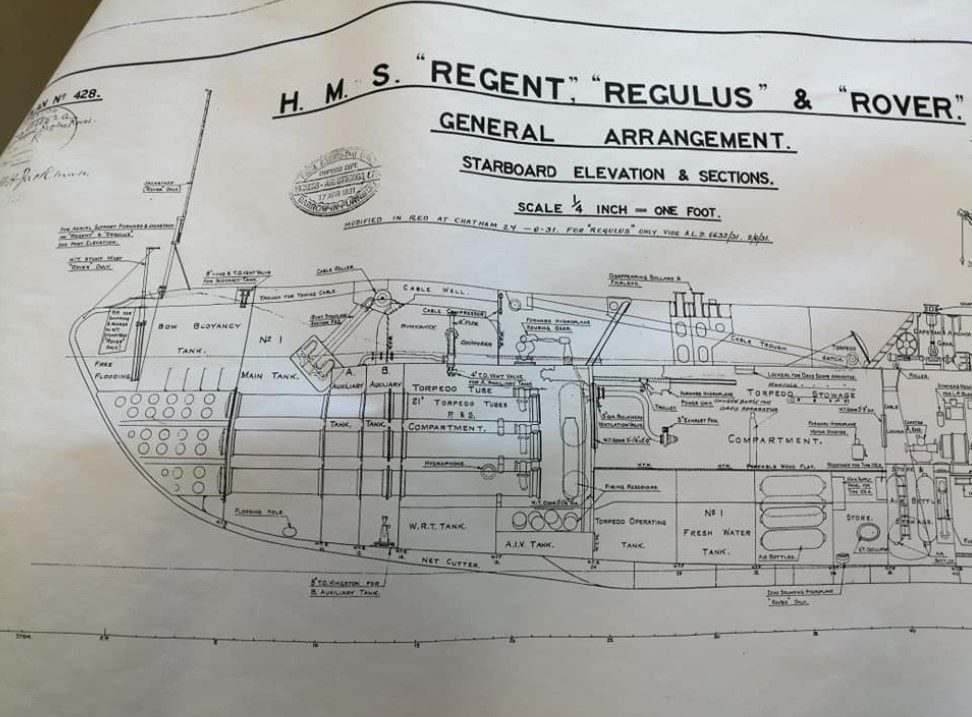

We found some particular points unique to British submarines. First of all, the hull of the wreck had the particular dimension and measurement that pointed to British design. Then, we arrived at the bow. The bow is of course upside down, but we found the area where the torpedo tubes were located. We found three on each side. Everybody knows, or at least wreck divers know, the bow section of a British submarine is unique in its class. A British submarine has a total of six torp tubes, instead of four like a German U-boat or Italian submarine.

But, in the center of the wreck, it’s gutted and open. We are sure there were two explosions. The first explosion by a mine, on the left side, and a second explosion probably detonated by the ammunition store. Of the wreck’s 87 meters in length, the visible part is about 65 meters and the rest is under the mud. We were not lucky with the visibility and extensive damage, so we have small proofs but enough to say for sure this is a British R-Class submarine.

Tell us about the dive itself.

The diving operation was with two boats and the dive team, Michele Favaron, Stefania Bellesso, both of Acquelibere Sub Padova, and myself, with research from Giuseppe Iacomino, in partnership with the Italian Naval League. We arrived on the point in the very early morning with my personal boat with Garmin. We already knew the wreck was there by previous scan. We set a lazy line on the seabed to mark the position. We prepared our equipment and cameras. The current was very, very, very strong. It’s not an easy dive, it’s very hard. It was hard to stay on the line but when we arrived on the wreck, the conditions were better and visibility was good. The wreck lies in about 75 meters/245 ft on the seabed, but the shallower part is at 57 meters186 ft. The dive was on open-circuit with 18-45 trimix as back gas, and 50% and 100% deco gasses. About 25 minutes bottom time and 45 minutes deco.

What’s next for your team?

We are involved with the Pentagon in the finding of some U.S. bombers ditched in the Adriatic sea and the finding of still-missing submarines nearby. We are also working with a university on the study and the maintenance of present wrecks and future projects.

Fabio and his team published an extensive report about the discovery with the help of the Italian Naval League, which provided logistical support. Here’s an excerpt describing the dive:

“Operation N 41 has finally come to an end, the scout ENDURANCE sailed from Manfredonia on 20/05/2022 at 9.30 am to Villanova arrives on site at 15.00. The team, made up of Fabio Giuseppe Bisciotti and Giuseppe Iacomino immediately returned to the sea towards the REGENT point, thus ensuring the planned dive point for the following day. The diving team, composed of Michele Favaron, Stefania Bellesso and Fabio Giuseppe Bisciotti reached the diving point at 7.15 UTC +1. At the moment of the descent there is immediately a very strong cross current such as to force the team to use the treadmill line in order not to lose energy.

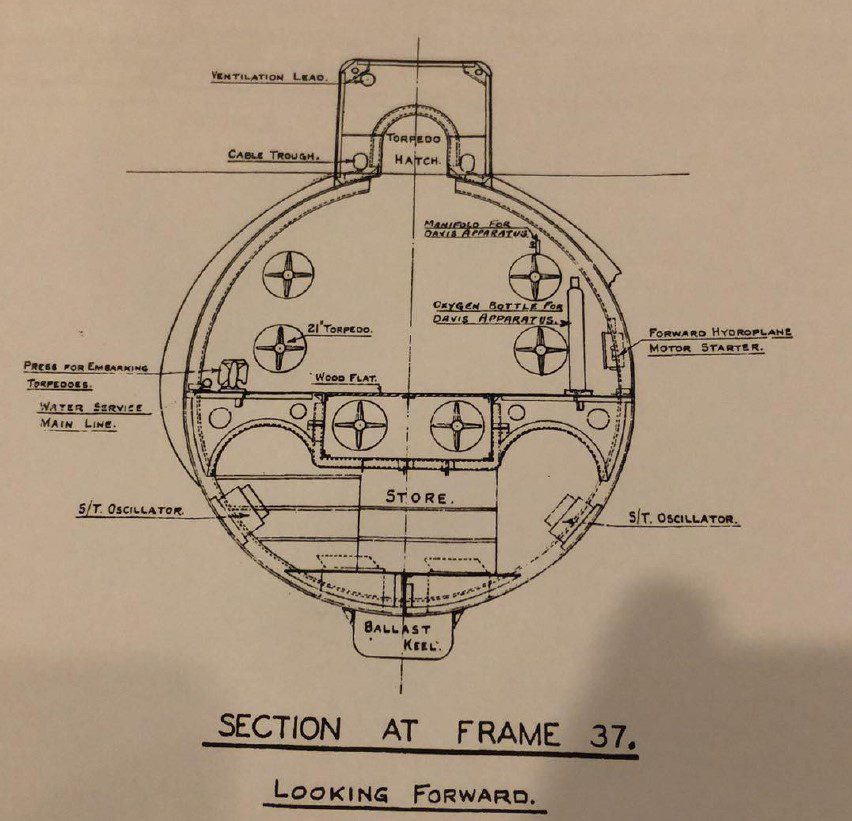

Touchdown of the wreck at an altitude of -60 meters where it was found that the body appears to be overturned by 180 with the rostrum cutting cables along the entire keel clearly visible.

The protuberance noted and photographed undoubtedly has the function of a cable-cutting rostrum. The design is typically English of R-CLASS as the height of this rostrum is 11.5 inches, or 30 cm appropriately calculated with line. The entire body of the wreck has been shaped and the total length is 87 meters, which is the length of a R-CLASS submarine. The remaining models such as classes P, T, S, and U do not possess such dimensions (P) or design (T, S, U) such that they can be traced back to the rostrum studied. The photo taken at the stern shows exactly the rostrum and is completely identical to the drawing of the construction plans. Please note that only the R-CLASS possesses these characteristics. At the height of the gutted point, the rostrum appears strongly deformed due to the violent explosion of the mine.

The ovals shown in the photo do not belong to the turret as you might think but refer to the lower ventral band of the hull in the area between the waste oil recovery and batteries n. 2 and n. 3, exactly below the engine pistons. By looking in the construction plans they are easily identifiable and have been found exactly in the same area. As a first impression the HMS REGENT struck a mine on the left side which undoubtedly initiated a second detonation below the casemate of the 122 mm gun. The explosion did not disable the submarine but literally gutted it.

Currently, the possibility of penetration inside the wreck is excluded due to the structural impossibility of ensuring easy entry and exit. Further studies will be started later for the safety of the wreck itself.”

DIVE DEEPER

Operation Regent-Bausan Report by Fabio Bisciotti

Rapporto Regent-Bausan (Italian) by Fabio Bisciotti

InDEPTH: Surveying and Identifying a Sunken JU 88a German WWII Aircraft (2019) by Fabio Biscotti

InDepth Managing Editor Ashley Stewart is a Seattle-based journalist and tech diver. Ashley started diving with Global Underwater Explorers and writing for InDepth in 2021. She is a GUE Tech 2 and CCR1 diver and on her way to becoming an instructor. In her day job, Ashley is an investigative journalist reporting on technology companies. She can be reached at: [email protected]