Education

Stay Warm – It’s A Piece Of (Layered) Cake

Fourth Element co-founder Jim Standing gets warm and fuzzy on the virtues of undergarment layering, and some of the specifics of Fourth Elements thermal options. No one is going commando!

by Jim Standing

In Germany, the time-honoured principle of layering for thermal performance called “Zwiebelsystem,” which literally translates as the “onion system,” means selecting the appropriate layers for various environmental conditions. But onions aren’t to everyone’s taste; to paraphrase the talking donkey in the movie Shrek, cakes have layers too, and everybody likes cake.

The concept that layering is the optimal technique to provide thermal protection came to scuba diving from the wider, outdoor-sport world. The model that most divers have come to adopt ever since Fourth Element launched the first base layer—the Xerotherm—designed exclusively for drysuit diving, is a good base layer, a thermal mid-layer (or two), and an outer shell.

The basic principle is pretty straightforward. Not only do the fabrics themselves hold air in their fibres, but by using layers, air is also maintained in the spaces in between, and it is this that provides the insulation you need. Choosing your combination of base layer and thermal layer is then a matter of assessing your needs, which are mostly determined by the temperature of the water and the planned dive duration.

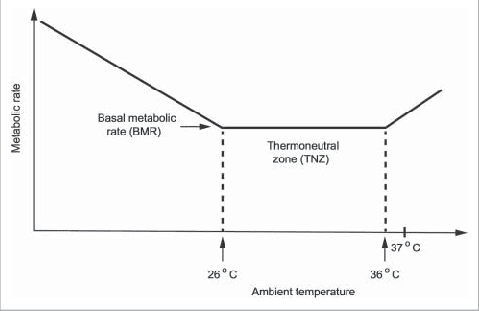

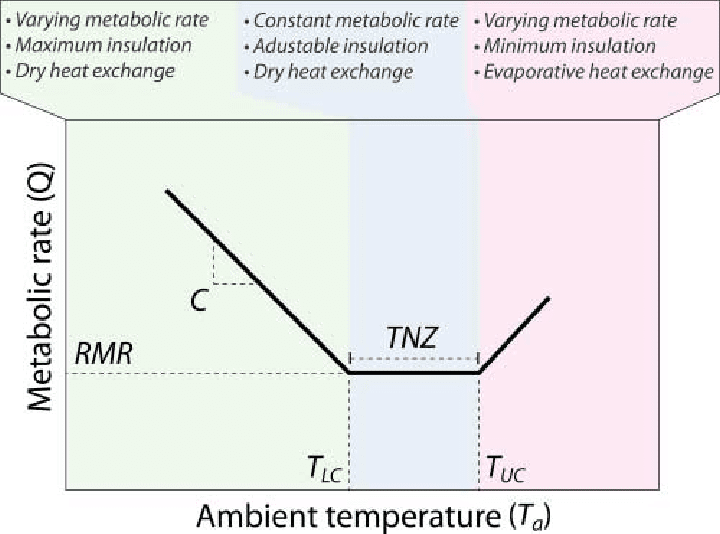

Our bodies are amazing machines, capable of regulating body temperature through passive and active means, from vasodilation or constriction and redistribution of blood flow to sweating and shivering, along with an incredible array of less obvious controls. All this is designed to keep our bodies functioning at a steady 37º C/98.6º F. But sometimes they need a little help. In the case of diving, exposure is almost inevitable as you are immersed in water at a lower temperature than the human body, meaning that there will always be heat loss along the temperature gradient. The diver’s insulation is designed to slow this loss down.

Ready Layer One

A good base layer is critical—it must manage moisture and keep your skin as dry as possible. Whether you like it or not, there will be some moisture inside your suit; hopefully, it’s just from perspiration, but at some stage it is likely that it will also be water from a leaky seal, a zipper or a more catastrophic leak. Keeping this moisture away from your skin is the job of a good base layer.

Water Is Wicked

Water is not a good insulator. Its specific heat capacity (the amount of energy that it requires to warm up by a mere 1 degree) is 4.2 times greater than air. In short, water next to the skin absorbs heat, drawing it away from the body and making you cold. Wicking is the process of moving water through a fabric from one face to another.

In the case of the diving base layer, its objective is to keep the moisture on the outer surface of the base layer away from the skin, maintaining a layer of air, a much better insulator, as the first line of defence against getting cold. If your undersuit also wicks, then this moisture will be moved even further away, and performance is maximised.

Use a super-light wicking layer like the J2 for layering under any undergarment to manage perspiration and small suit leaks without affecting buoyancy. It has a grid patterned knit, maximising the air next to the skin, but wicks moisture away very quickly. The added advantage of silver ion impregnated fibres minimises the growth of microorganisms such as bacteria, making this the perfect base layer for drysuit diving trips in which multiple days of diving are planned.

We designed it for some of the most extreme diving expedition conditions to maximise performance whilst maintaining healthy skin of the dive team over a continuous period of more than two weeks. The lead divers on the US Deep Cave Diving Team’s 2013 J2 Expedition, Phil Short and Marcin Gala, wore this layer for 19 days underground and whilst neither would vouch for its odour-reducing capabilities, Marcin’s comment, having previously suffered with skin infections, was, “It was a life saver.”

Use the Xerotherm to provide good wicking performance, coupled with great thermal protection. Adding this as a base layer to your undersuit makes a significant difference. It’s one of the fastest wicking materials available, and thanks to this fabric technology, it works so well when wet that some divers do not notice leaks in a suit until after the dive!

Choose the Right Undersuit

There are so many to choose from and many of them work on the principle that the thicker the undergarments, the better they will be. But that is not always the case: fabric technology, wicking and biomapping (identifying key areas of exposure) all play a part in designing an undergarment, and then there is the ultimate test—will it perform under a drysuit?

Fourth Element designed the Arctic undersuit for use underneath neoprene drysuits. In cold waters, layer this with a J2 base layer, or Xerotherm for extreme temperatures.

Under trilaminate drysuits, we recommend the HALO 3D, but many divers also choose the Arctic for the ultimate versatility of using it in warmer conditions and layering up more for the cold. In a correctly fitting trilaminate drysuit, there will be more room for undergarments, but it is important not to have so much bulk that movement is restricted.

The appropriate combinations will change with four variables, water temperature, duration of dive, frequency of diving and personal factors – some of us just feel the cold more (or maybe are just willing to admit it)

The Arctic undersuit is typically used for dives of up to an hour in temperatures from 10º–16ºC/50º–60º F.

The Arctic Expedition was developed for temperatures from 6º– 14ºC/42º–57ºF.

The HALO 3D was developed for temperatures of 4º–10ºC/40º– 50ºF.

In really cold/long exposure conditions, add an additional base layer or other insulation to the body core. For example, a Xerotherm vest will not change your buoyancy but will add more comfort. The X-core vest, developed by Fourth Element as a passive heating garment should be worn either next to the skin or over the baselayer, but provides significantly greater thermal protection.

Turn Up the Heat (but only if you must)

For some of the most extreme divers doing long dives in cold water, active heating using a battery may be required. This involves task loading, additional equipment and the increased risks of something going wrong. If using active heating systems, we recommend wearing these over the base layer, but ensuring that adequate passive thermal protection is also worn in the case of equipment malfunction.

In an ideal world, to avoid the potentially catastrophic effects of heating equipment malfunctioning midway through a dive, active heating systems should be reserved for the return from the deepest point of the dive and thought of as assets for a more comfortable decompression. Remember, repetitive diving in cool water will result in longer term thermal stress to your body, and insulation that felt adequate at the start of a week of diving, may not feel so good half way through the week, especially if dives are long and tiring. In these cases, an extra base layer top can be employed to great effect to get a little more comfort.

Stay Cool and Dive Smart

Finally, don’t overcook it. There is plenty of emerging evidence that the best way to dive is just comfortable, and maintaining this for as long as possible—keeping your body in the thermal neutral zone where it is able to use its own thermoregulatory systems without resorting to extreme sweating for example.

Dive Deeper:

A Beginner’s Guide to Drysuit Layering

Jim Standing founded Fourth Element with Paul Strike in 1999. He studied Natural Sciences at Cambridge University and specialised in, among other things, animal energetics and the physiology of diving mammals. This led to him frequently being found at the bottom of a bath at different temperatures often in various stages of hypothermia, experimenting with metabolism, thermo-regulation, and skip-breathing. He would love to say that this experience set him on the journey to develop some of the best thermal protection in the world, but that was mostly driven by getting cold whilst diving, an experience which drove him and Paul to question the gear they had, and to wonder if they could do better.