Community

I Died Saving Another

As we’ve come to understand—thank you author Stratis Kas and Human Diver—”close calls” during diving operations are more common than most people realize. But how many divers have lost their lives trying to save another? Photographer/videographer Nico Lurot has. Thankfully, he was brought back to life, and is therefore able to share this harrowing, thorny tale.

Text and images by Nico Lurot.

During a recent photographic trip, I developed a good camaraderie with a few other photographers onboard. One evening, we were all sharing dive stories, and much like the iconic scene from Jaws where Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw were playing a game of one-upmanship by comparing scars, we were doing the same, trying to one-up each other with our close call dive experiences. I listened to a few people’s stories but had to eventually interject: “These are all cool stories, but did you die?”. They looked at me puzzled and one replied, “Did you? The short answer was “Yes.” This is the story about how I did.

Some context is needed though. In 2010, I set up Thailand’s first underwater imaging academy, with a team of divers whom I had worked with for a few years and trusted not only as exceptional filmmakers but also as world class dive guides. We wanted to create a hub in a highly saturated recreational market that offered something different: 1-1 dive guiding for underwater photographers and videographers of all levels.

The idea proved to be highly successful, but had one obvious limitation: diversity of dive sites. Phuket, Thailand, is blessed with a great diversity of local sites ranging from between one and a half to three hours away, and offers everything from wrecks and reefs to wall dives and muck dives. However, all in all, there are only about 15 sites, which meant it was hard to keep clients coming back year after year. While clients liked the service provided, like all divers, there was always the yearning for something new.

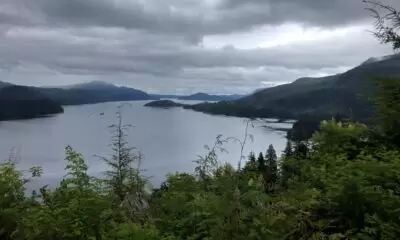

My close friend, Takuya, one of the best dive guides I’ve ever known and an encyclopedia of marine life knowledge, suggested we expand our reach. We decided to charter the Scuba Explorer liveaboard for a season (image below), to fill the vessel with underwater photographers and do something that the local market called us “crazy young idiots” for, venturing to dive sites that were supposedly not reachable from Phuket.

Takuya and I chose the Scuba Explorer because of her size and the size of her fuel tanks. We figured out that if we cruised slowly, we would be able to reach an area called the Adang Archipelago, right on the border of Malaysia in the south. It has always been possible to dive Adang, but to reach it normally involved taking a plane ride to Hat Yai (a southern Thai province) and then spend a long day and half minivan ride through a part of Thailand known for terrorist attacks. Needless to say, tourists are rightfully advised to stay away from there. Understandably, divers tended to avoid Adang. Although the archipelago itself was perfectly safe, the journey there by minivan was dangerous. Logistically, reaching it by boat from Phuket had never been done before.

We didn’t want to risk bringing clients onboard a test cruise, so we paid the expenses ourselves, with the hope that the trip would be successful. It was. Marine life was like nothing we could have anticipated. Due to the lack of divers and boats, the reefs were teeming with fish life. We saw species that were not known to us at our local sites, (Star-Eye Octopus), species that were not meant to be in Thai waters (Maldive Sponge Snails), huge tornadoes of pelagic fish like Rainbow Runners and Tuna, reefs that looked like they had never been damaged by diver interaction and, to top it all off, during a surface interval, we were greeted by a swarm of devil rays that jumped out the water as if to welcome us, all caught on video (below).

Training New Staff

Once we returned to Phuket, we began to market this trip, and the bookings came rolling in. Then we had a new problem: keeping our 1-1 guiding promise on a liveaboard. The size of the vessel was not the problem. The problem was the amount of staff I had whom I trusted to deliver the service we had come to be known for. So we launched an initiative to train people to become underwater photographer guides.

Here comes the scary part. On one of our cruises to Adang, we were welcoming onboard a new trainee, who out of respect shall remain nameless. He had come highly recommended by one of my colleagues at Discovery channel, so I was really looking forward to seeing what he could do. However, you know when you get a certain vibe from someone? You just know instantly that they’re going to be trouble? That’s what happened to me the moment he stepped on the boat, despite his glowing references. His whole energy was off. He was arrogant, too sure of himself, and gave a “seen it all before/nothing new you can teach me” vibe.

The staff felt it too, and told me they did, so I suggested he accompany me. I thought that, if he was with the “boss,” he would be less likely to cause me trouble. That was the hope at least. We reached our first dive site the following morning, an easy-going dive in the Phi Phi Island Marine Park (known for being the location where “the Beach” with Leonardo DiCaprio was filmed). To his credit, the new trainee seemed to know what he was doing. He was proficient at finding and identifying species, and definitely had an understanding of what an underwater photographer needs from their guide. I was happy, the client we were looking after was happy. Maybe I was wrong about this trainee?

On to the second dive, I wanted to see what he was like with a camera underwater. I assumed the role of guide again on this dive, and instructed the trainee to take up the rear, and multi-task both photo taking, being aware where we were at all times, and being on the lookout for any unique species. The area was called Koh Haa, famed for having some stunning decorated caverns and beautiful reefs.

Danger, Danger

Toward the end of the dive, we were finishing off along a wall, but the swell started to pick up and there was a risk of being bashed against the wall. I signaled that we do our safety stop away from the wall, and both the client and the trainee replied with an “ok.” sign. After swimming out a few meters and when ready to surface, I turned around to signal “go up,” only to find I was minus the trainee. I looked back over toward the wall, and spotted him attempting to take a photo of a clown fish. Of all things, a clown fish!

If you’ve never attempted to take a photo of a clown fish before, I can tell you they are notoriously tricky to get good images of. They live in anemones, they never stay still for long, constantly coming in and out of the anemone. Add to that the difficulty of the large swell, and any attempt to capture this clown fish was just not going to be possible.

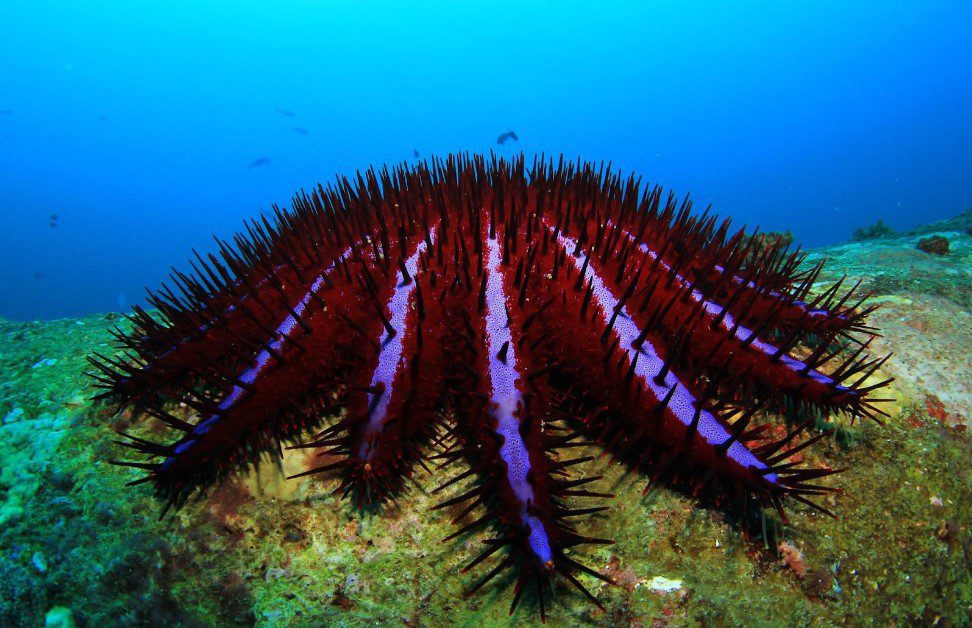

And here’s where the trainee made a massive error. He became so focused on trying to get this difficult subject in equally difficult conditions, that he made the decision to hold onto something to try and stabilize himself, and because he was so narrowed in on this clown fish, he wasn’t looking where he was about to put his hand. To my horror, he was about to grab onto a crown of thorns starfish (image below), a highly venomous pin prick battle tank of an animal.

Now the following was split-second reaction stuff. I had to speed over to him in an attempt to save him, but how? If I tried to grab him, it would surprise him and he would pull away, likely impaling himself onto the crown of thorns. Imagine a time when a sound has made you jump, you instinctively jump away from it in fear right? Same thing here. So, my second thought was to grab him by the tank and pull him away. The problem with that was that by the time I reached him, his hand would be so close to the crown of thorns that the natural whiplash caused from yanking his tank would risk pushing his hand onto the starfish.

As I said, this was split-second thinking … The last possible solution I had was the reverse of the first idea. Instead of grabbing his hand from the top and risking him pulling away towards the starfish, I would put my hand between his hand and the starfish and tap upwards, hopefully surprising him and making him pull away in the opposite direction. At least logic dictated that he should pull away. After all, if something surprised you, you would surely move in the opposite direction right?

Unfortunately for me, this didn’t happen. The trainee, against my definition of logic, felt my hand against his and instead of pulling away, slammed me down onto the starfish. The pain was like nothing I’ve ever experienced. The puncture wounds where the thorns had penetrated my thumb began literally gushing blood. I managed to make it back to the boat with both client and the trainee, where I apologized to the client for rushing off and explained what had happened.

Once Bitten, Don’t Die!

I began sweating profusely as a reaction to the venom. Then I vomited, and then I blacked out. I woke up (Takuya told me it was a few minutes later) and was shivering uncontrollably, not good when you consider the outside temperature was 37° C/98° F. Clearly the venom was having a serious effect and was getting worse every moment. The closest hospital was back on Phi Phi island, about an hour away. The sweating, vomiting, blacking out, shivering cycle repeated every 20 minutes or so while on the way to Phi Phi. I began to feel very weak.

When we reached Phi Phi, we were told the doctor had taken the day off and was unreachable. The only person there was a nurse, whom we had to show a photo of the crown of thorns too, so she could understand what had poisoned me. She replied in Thai, “Mai Dee,” which directly translates as “Not good”. No kidding! She gave me a multitude of drips directly into the vein in my right hand, but said I needed medical attention from the mainland. Takuya rushed out onto the beach, found the smallest speed boat with the biggest engine (less weight with a big engine obviously equals more speed), and chartered it back to Phuket. Normally the journey time between Phi Phi island to Phuket is one and a half to three hours, depending on the vessel. This little speedboat did it in 25 minutes.

Takuya was doing everything he could to keep me from blacking out on the way back. What was scary was that I began to find it increasingly hard to breathe. When we got to the harbor, the ambulance was there waiting for us. Takuya told them what happened and what my reaction to the poison had been. They explained that since it had been close to two hours, I was lucky to have kept breathing, but that I was going into anaphylactic shock.

The next thing I remember is arriving at the hospital, being rushed in, seeing hospital lights overhead passing by. Then I honestly don’t remember what happened. I woke up and saw three faces I didn’t recognize (but who were clearly medical professionals) and Takuya’s face all looking down at me in shock. Takuya shouted “Nico-san! Are you okay?”

In complete surprise I answered, “Yes mate, feeling a bit rough, but I’m okay. Why?” His response will stay with me forever. “You flatlined!” When someone says that to you, you have an awfully strange feeling—almost a feeling of emptiness, like, it’s that easy? I believe my response was something along the lines of “Huh?” He pointed to the electrocardiogram, which I realized in my dazed state was attached to me, and he said “You flatlined! You were out cold, we were all talking and then we heard, “beep.. Beep… beeeeeeeeep.” You died Nico-san! Are you ok?”

What happened between arriving at the hospital and waking up to faces saying “You died” is all a blur. I remember nothing. I don’t have any poetic closing to this, not any life lesson to share, nor some story about the other side, nor any “My life flashed before my eyes” recount to tell. The reality is that I walked away with my life, which I’m hugely thankful for, obviously. But the whole thing made me question if I did the right thing. The honest answer is I think so. That may be the only take-away from this story for anyone who has dealt with a near-death or death experience when diving. Don’t question what you did. Don’t ask, “If I had done things differently, would I have gotten a better result?” because the reality is, you don’t know. Needless to say though, we did not keep this trainee onboard.

In hindsight, I came out okay (although minus a chunk of my right thumb which was surgically removed), and no one else was hurt. The point of this story is not only to share how quickly something can go wrong, but what the potential cost of trying to save someone is. It was very scary, I ended up ok, and no one lost their life. Crisis somewhat averted. I wouldn’t even hesitate to do it again, despite what happened to me. The idea of having someone I was responsible for die, would be unbearable. I’m happy that I had such quick, instinctive reactions and stopped another from getting hurt. The end result is everyone is safe and maybe it’s a great story to tell my daughter one day.

Nico Lurot started diving at age 10 and has made more than 3,000 dives all over the world. He filmed underwater in South East Asia for nearly a decade between 2006 and 2015, working with some notable production houses along the way. He has been a GUE diver since 2018, and his desire to share his passion for underwater photography & videography with our community is evident. Nico runs with GUE’s YouTube channel and is working with GUE’s marketing and media team on social media development, and GUE’s outreach.