Community

I Trained “Doc Deep”

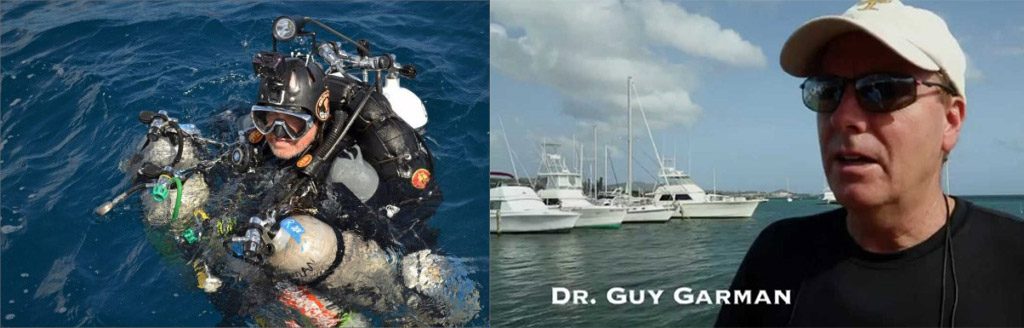

Numerous divers have died trying to break scuba depth records over the years, and the losses continue. Their deaths not only impact their families, friends and their support teams, but the diving community as a whole, as technical diving instructor Jon Kieren knows first hand. He was Guy Garman’s aka “Doc Deep,” first tech instructor and friend, who ultimately tried to dissuade Doc from attempting his 2015 dive to 365m/1198 ft, which proved fatal. Here is his story.

by Jon Kieren

As I look back at my career so far, there are plenty of things I wish had done differently, students I know I should not have passed, and divers I continue to worry about. It’s all a part of building experience as an instructor, but there’s one that will haunt me forever.

Almost eight years ago, I got a text message that I knew was inevitable. I had been having nightmares about it for years, including just the night before. I had prepared myself the best I could, but it’s still one of the worst things a dive instructor can experience.

“Guy didn’t come back”

For several years prior, I fought to stop the monster I believed I helped create. A constant knot of regret, fear, and guilt lived in the pit of my stomach. When that text finally came, sad as it was, I knew I would no longer have to wait anxiously for the foreseeable bad news.

Throughout my career as a technical instructor, the topic of depth records and Guy Garman’s name has come up frequently. It’s always been a tough discussion for me to navigate. Wanting so badly to defend the man who was like family to me, but too embarrassed and guilt-ridden to discuss it. I bit my tongue as armchair quarterbacks and keyboard divers ranted about how stupid he and his whole team were with little to no knowledge about him as a person.

Thankfully, after a few years, those discussions slowed down a bit, and I thought the days of depth records were finally gone. But, with recent record attempts reigniting the same discussions, I thought it might be time to finally share what I know about Doc Deep and how he came to perish at the end of that line 365 m/1200 ft below the surface.

Like anyone, Guy had his flaws. However, most of them were due to his incessant need to be the best at whatever he was doing at that moment. He led a truly extraordinary and passionate life, which ended as extraordinarily as it began.

He grew up in the Amazon jungles of Peru with the Aguaruna natives where he was nicknamed “Hummingbird” because of his constant buzzing about and his need to be involved in and understand everything. I remember listening to his stories of hunting crocodiles as a young boy with his native brothers, and his pet jaguar that would walk him to school and guard his bedroom at night. In my eyes he was truly a Renaissance man—marathon runner, alpine climber, and yet a physician in osteoplasty and head, neck and facial plastic surgeon.

Guy was certainly no stranger to hard work, sacrifice, danger, or pain. As a young man, I often turned for support and advice to this truly remarkable person who became one of my dearest friends. It’s unfortunate that most of what seems to be remembered about him is his lack of diving experience and fatally flawed dedication to accomplishing something he believed was important.

I’ll never defend his pursuit. In fact, I furiously opposed it for years, eventually needing to sever my relationship with him and the technical diving community in St. Croix, USVI, that I had built with such optimism and pride. However, I do believe it’s important to share what I know about how his fateful dive came to be so we can openly discuss the failures of the system that created this “monster” and try to put an end to these foolish pursuits.

One of the biggest criticisms (rightfully) was his lack of experience. But, to explain how he got where he was with so little experience, it’s important to understand the culture he grew up in. And this is where the weight of guilt sits heavily on my shoulders.

The Lure of Technical Diving

I found my passion for technical diving out of boredom, to be honest. Swimming for several years along the shallow reefs on top of the dramatic walls of St. Croix as an open water instructor, I was getting pretty burned out from the repetitive lifestyle and from seeing the same fish every day. So, as many 25-year-olds do when they’re bored, I started to do some pretty stupid stuff, such as single tank bounce dives on air to 75 m/250 ft … until I almost died.

After that, I decided to get the fastest and cheapest technical training I could. I booked a flight to Honduras, and a few weeks later I was a hotshot technical diver. Heading back to St. Croix with no teammates, I did even more stupid stuff. At least this time I had doubles and deco gas with me, but I quickly realized I needed some teammates and maybe a squirt or two of helium. So back to Honduras I went, and another few weeks later, I was a trimix instructor. With less than a year of technical diving experience and full support from my instructor trainer, and within training agency standards, I went to 90 m/300 ft for the third time ever with students in tow. Because the agency signed off on my instructor ratings, I had no reason to believe I didn’t have the experience or know-how to be doing what I was doing. They said I could, so I had a blind and naive confidence that what I was doing was OK.

Doc Deep had just moved to St. Croix and started diving when I was getting the tech community going. Just after finishing his advanced open water course, he was wandering around our shop checking our gear when he saw the banner on the wall advertising us as a technical training facility. When he asked the shop staff about it, they gave him my number and we set up a time to chat.

Now, keep in mind, I was like 26 years old and thought I knew everything there was to know about diving. A beast inside me had awoken, and I felt like I NEEDED to go as deep as possible as much as possible. Then Dr. Guy Garman pulled up in his Mercedes to talk about technical training.

Guy seemed incredibly sharp, and excited about technical diving. Plus, money seemed to be no object. So, I signed him up for the third round of tech courses that I had ever taught. I made sure he met all of the minimum prerequisites and course requirements and, within a few weeks, he was a trimix diver. When we started talking about depth records, Nuno Gomes held the record at the time and as an invincible 26-year-old, I thought, “If he can do it, why can’t we?”

We dove a lot, and I taught a bunch of courses trying to build a team of local divers to help us explore deeper and deeper down the walls of our small Caribbean island. Guy supplied the helium. My partner at the time was my primary teammate, and we were then doing dives in the 120 m/400 ft range, with Guy acting as a support diver (and financier) for most of it. But after a bit, I could sense his frustration growing. It was clear he was not happy in a supporting role, and his ego was screaming that HE needed to be the one to dive the deepest.

I clearly remember one boat ride out for some 120 m/400 ft+ dive where he was acting like a grump. As I was about to descend, I told him not to worry, that he’d be next, and he shot me a look that made me realize our relationship was no longer an equitable one. That dive went OK, but it told me that I needed to think about the amount of resources involved, as well as the risk to us and the support divers. Perhaps it wasn’t worth it just to see a big number on a dive computer. After some soul searching, my dive partner and I agreed that we needed to change the way we pursued technical and deep diving, and leave the pursuit of “depth just because” behind us. Guy didn’t like that.

Over the next few months, we began focusing on longer duration dives at shallower depths as opposed to uber deep dives, and my partner and I built up some experience on our new rebreathers. Guy, however, distanced himself from us and started talking about how he wanted to be the deepest diver with our other teammates.

Around this time, I got offered a job in South Florida that I just couldn’t refuse, so I took it. I left a couple of months later. Before I went, I tried to have conversations with him and our other friends on the island about how I thought his pursuits were reckless with almost nothing to gain. But in the end, I just had to leave it at that and try to put it out of my mind as I created both physical and emotional distance from the whole situation.

The Drive For Depth

Over the next year, a couple of new tech instructors arrived on the island filling the void I had left. Eager to make a name for themselves, they quickly became wrapped up in Guy’s pursuits. I think this is where things really began to take a turn for the worse. The teammates who still remained on the island were very close with Guy, but they were reluctant to support him. However, with the newcomers’ encouragement, Guy continued to aggressively drive forward, earning the nickname “Doc Deep”.

They started going deep. Really deep: 152 m/500 ft, 183 m/600 ft, 244 m/800 ft. On one 600 ft+ dive, one of the new guys got severely bent. Even so, everyone pushed forward, many were convinced Guy was the one to break Nuno’s record. In 2014, Ahmed Gabr reportedly reached a depth of 332 m/1090 ft, and Guy decided to aim for 365 m/1200 ft.

I couldn’t ignore what was happening anymore when I started seeing the social media posts about their plans and hearing the same from the team at events like DEMA and TekDiveUSA. I pleaded with my friends to not support him, knowing full well what would happen if they continued. They insisted if they didn’t help him, he would do it alone. I believed them, and understood the position they were in. So, I implored the training agencies to publicly condemn these pursuits of irresponsible and dangerous record breaking attempts for their own sake, and to warn the professionals involved, but they wouldn’t take a position.

The momentum seemed to be unstoppable at this point; this thing was going to happen no matter what. I said “goodbye” to Guy after a dinner we shared at TekDiveUSA in 2014, with me knowing it would likely be for the last time.

Week after week, the knot in my stomach grew, and then the day came that I had been dreading.

Of course, the news spread quickly through the diving community, bringing extremely harsh criticism to all of those involved in the form of articles, blog posts, and forum rants. It was hard to keep my mouth shut, but I just couldn’t get involved. I was sad, angry, and became quite depressed. Even though, rationally, I couldn’t see how I could have done anything differently, I felt guilty. I wasn’t alone. Guy’s close friends and family were deeply affected. Most stopped technical diving or diving altogether. One drowned himself in rum and is still fighting to come back.

My relationship with these people was fractured. I couldn’t help but be angry even though I knew they were only trying to do the best they could to keep him alive. Others who advertised themselves as deep support specialists continued to offer services to help divers achieve extreme depths. As could have been predicted, accidents happened and people got hurt, but that didn’t seem to stop them. Not until very recently, has the frenetic pursuit of deep water record breaking seemed to slow a bit.

So what went wrong on the dive? It wasn’t anything significant, because it doesn’t take a lot at 365 m/1200 ft. Guy’s family has GoPro footage, but the details haven’t been released to the public, and it isn’t my place to do so. All I can say is that successfully diving that deep—and living to tell about it—is more a matter of luck than skill. If anything goes wrong, it’s almost impossible to recover from; and if someone does succeed, I believe it’s simply because it wasn’t their day to go. What do we learn from these stunts? Nothing. We already know what it takes to put a diver that deep, it’s just not with scuba.

The Aftermath

In Mexico, I questioned a recent depth world record team who asked, “What did we learn?” In their formal presentation, they claimed their reason for not using rebreathers or habitats was that the team didn’t have the knowledge or experience to do so, and gaining that experience would be too expensive and time consuming. They used very low helium content mixes trying to avoid HPNS, but suffered severe narcosis and CO2 issues, making it impossible to manage an entanglement at depth and very nearly resulting in an uncontrolled ascent from an absurd depth that was only stopped by sheer luck. They responded to my “What did we learn” comment by stating that, in the future, they might use more helium and rebreathers. These are all things the vast majority of the technical diving community have understood for over a decade, but they just never thought to ask people who were actively doing extremely big dives almost every weekend.

I recognized a clear similarity in the two teams, a strong reluctance to seek or accept advice from those who were far more knowledgeable and experienced than they. Almost like they thought if they did it all themselves from scratch, that they would find some magic trick nobody had thought of. Or maybe they were just trying to avoid being told that what they were doing was reckless. Either way, one team got lucky, the other did not.

So where do we go from here, knowing that these reckless boundary pushing personalities will always exist? I think we have to encourage training agencies to publicly speak out against depth records and petition Guinness to stop acknowledging them. Most importantly, I think we need to raise the minimum standards for instructors so that only those with a significant amount of real-world dive experience are guiding new technical divers into the world of deep diving, and are doing so responsibly. I absolutely should not have been qualified to teach Guy Garman technical diving. I was at the absolute peak of the Dunning-Kruger effect when we began our relationship, as was he when that fateful dive took place.

As instructors and industry leaders, we need to watch and listen for clues in our students that their motivation might have more to do with record breaking and ego than competent diving and worthwhile exploration, and set them right when and where we can. This is a skill that instructors need to develop. I was too young and too excited about tech diving to see the signs at the time, and suffered the ultimate consequence.

However since working with Guy, I’ve refused to issue certifications, withdrawn students from classes, and severed working and personal relationships when I see individuals unwilling to accept that the limits apply to everyone. It’s a tough discussion to make, but as instructors we need to try to guide students in a responsible way.

This doesn’t mean we need to condemn pushing the limits. Most of us are here because we want to discover what we are really capable of. But mentoring divers to show them what limits can reasonably be pushed, and which ones (like depth records) simply cannot, is important.

Pushing a boundary should really only be tolerated if there is something to learn or discover, in other words, if it’s a risk worth taking. Otherwise we’re just apes beating our chests.

Guy left a huge hole in my heart when that text came in, but I try to use it as a reminder of the impact I have on aspiring divers and the importance of reinforcing a conservative approach to technical and cave diving. While this is probably the hardest thing I’ve ever written, I think it’s important that we speak openly about these types of events so others can learn from them.

See Companion Story: The Risk and Management of Record Chasing by Neal Pollock PhD

Dive Deeper

Wikipedia: Guy Garman

Undercurrent: A Fatal Attempt at a World Record (2015)

Men’s Journal: Prominent scuba diver presumed dead after world-record attempt off St. Croix by Pete Thomas

Scuba Tech Philippines: Guy Garman: World Depth Record Fatality by Andy Davis

Scubaboard: Doc Deep dies during dive.

Others stories by Jon Kieren:

InDEPTH: SUMP POTION #9 by Jon Kieren

InDEPTH: Grokking The FATHOM CCR: My Dive into the Nuts & Bolts with the Inventor by Jon Kieren

Jon Kieren is a cave, technical, and CCR instructor/instructor trainer who has dedicated his 13-year career to improving dive training. As an active TDI/IANTD/NSS-CDS and GUE Instructor and former training director and training advisory panel member for TDI, he has vast experience working with divers and instructors at all levels, but his main professional focus resides in the caves. In his own personal diving, Jon’s true passions are deep, extended range cave dives, as well as working with photographers to bring back images of his favorite places to share with the world.