Community

ICE: How Intrepid Souls Spent Their Winter Lockation

How do you #DiveLocal when a pandemic is raging and all of the local surface water is frozen? Climb into your Arctic Expedition, grab a saw, channel your inner Wim Hof, and prepare to go hyperbrrric—the water’s jjjjjust fffffine!

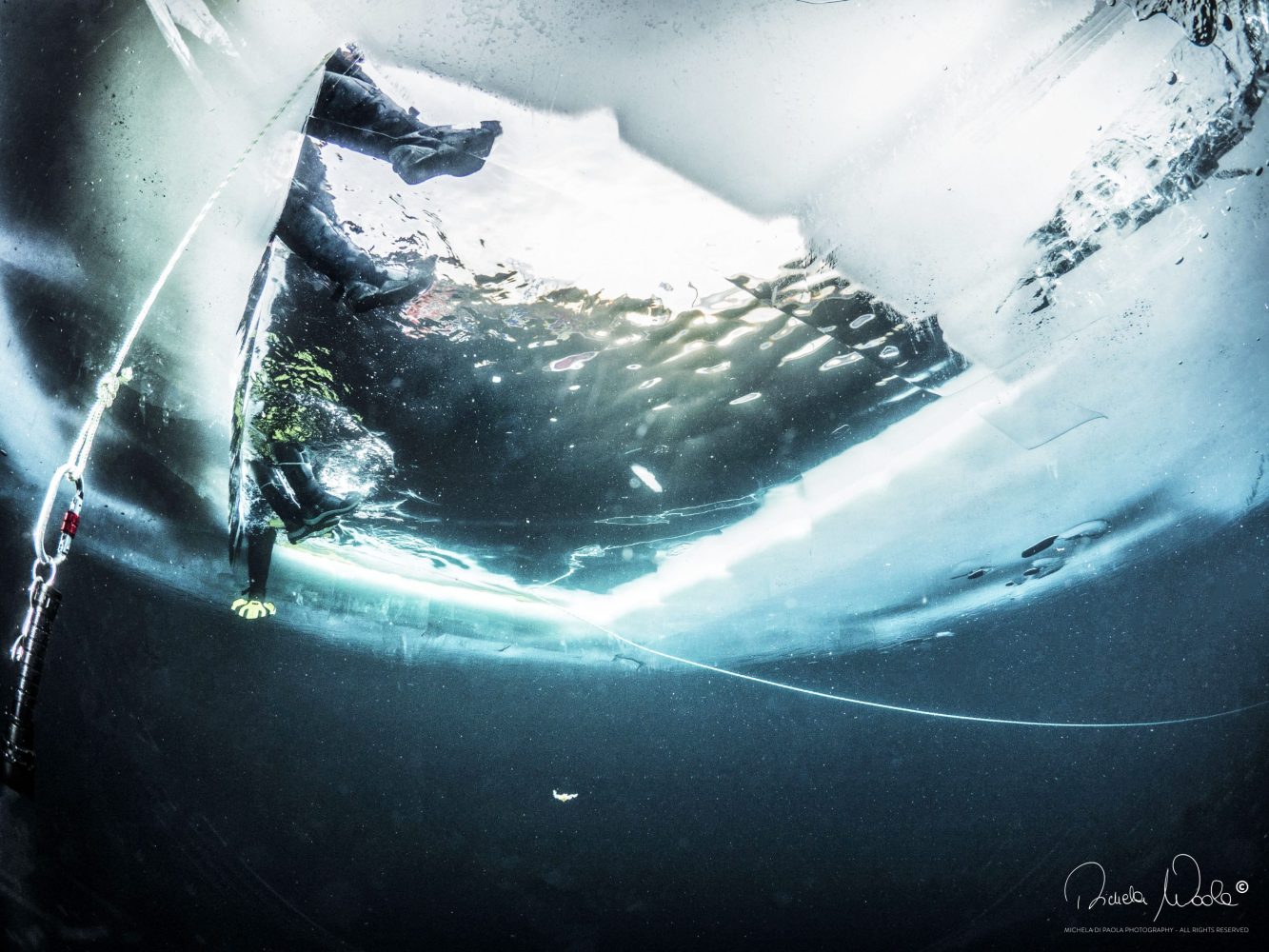

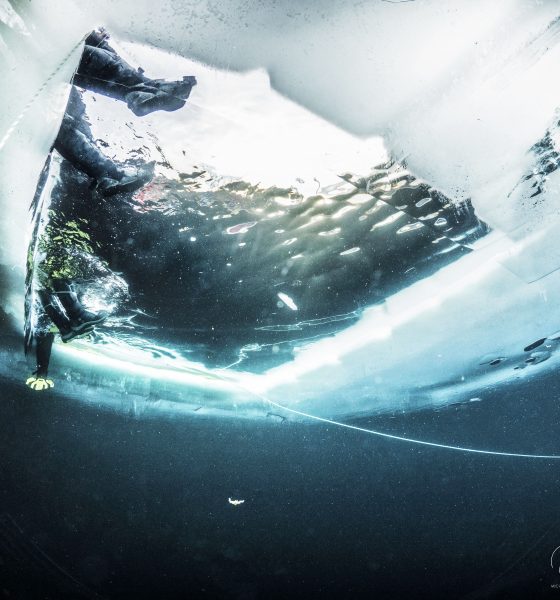

Header image by Michela Di Paola Photography.

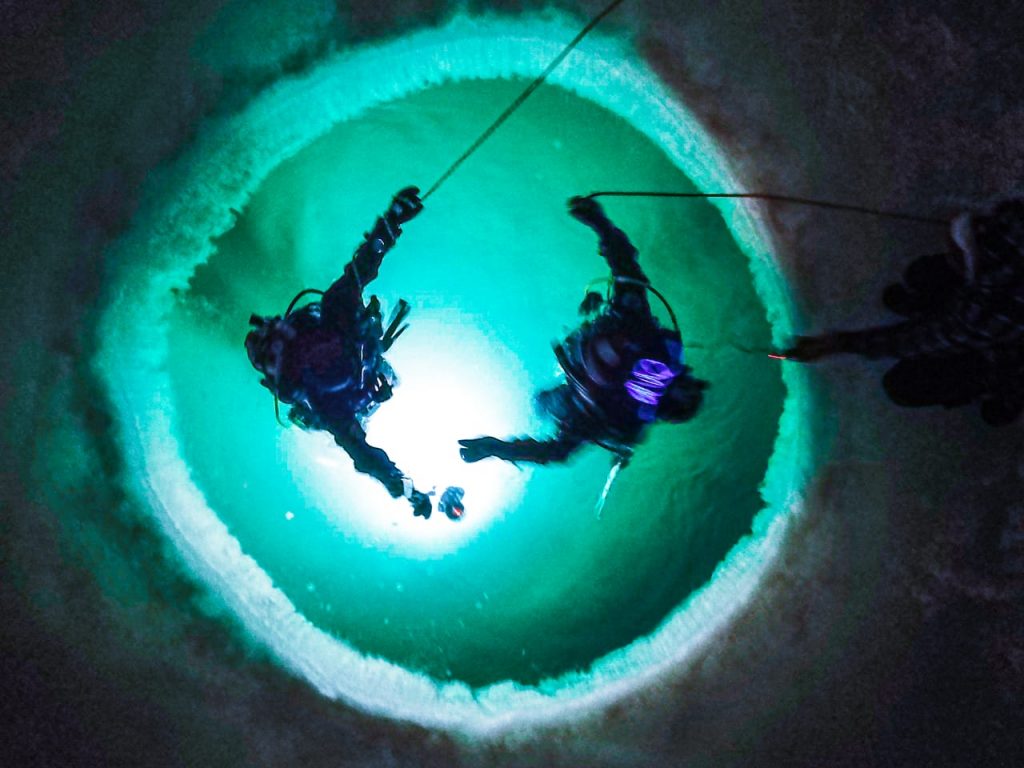

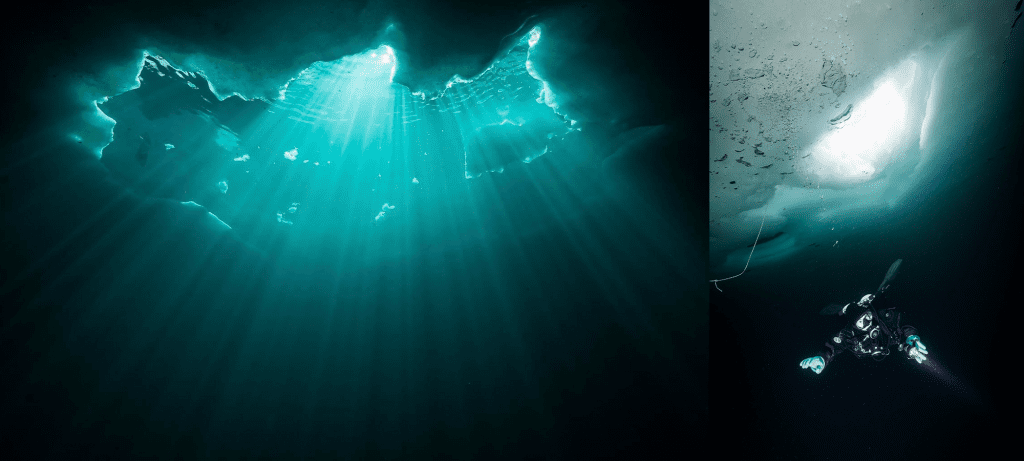

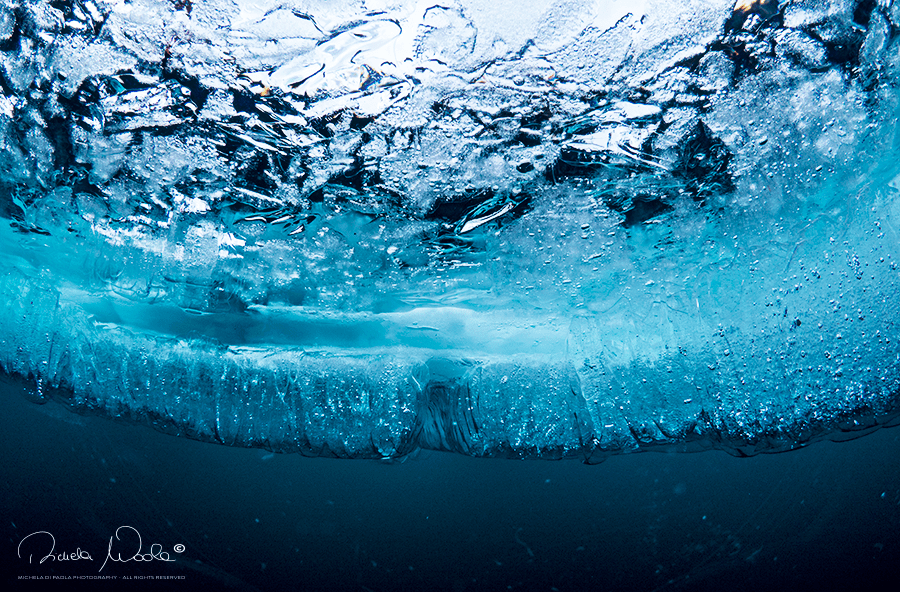

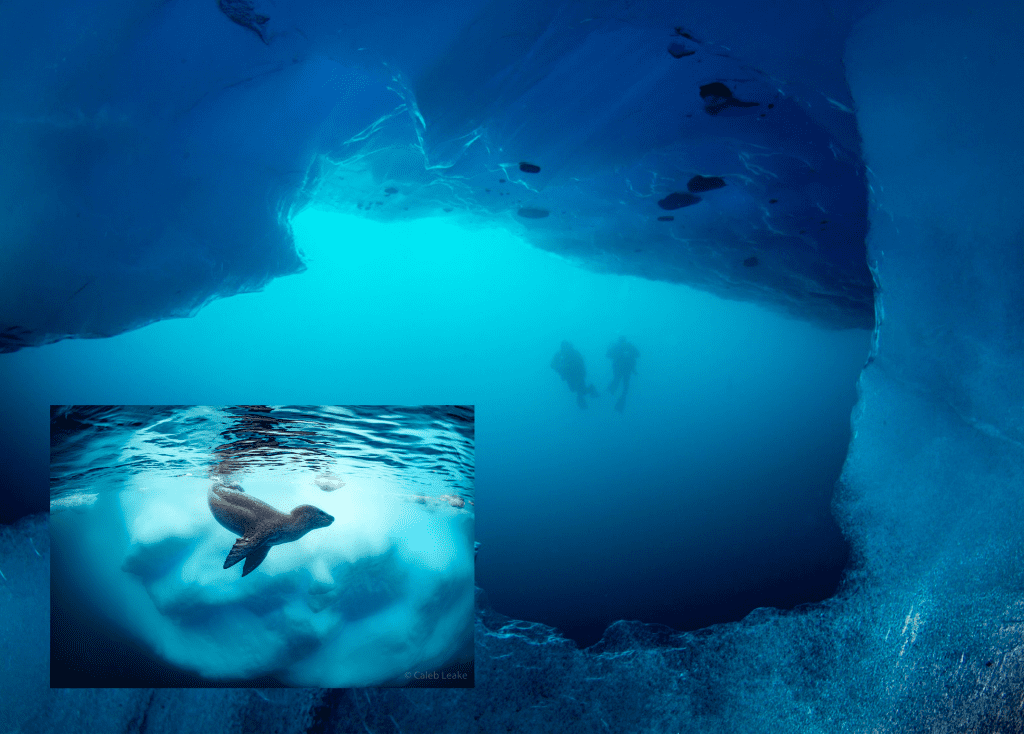

“I’m under the frozen lake’s surface and I can observe the layer of ice on top of me and the sunlight penetrating from the hole. I’m in a new dimension where, surrounded by deep silence, I can still perceive and observe the silhouettes of the persons on the surface.” Michela Di Paolo

Welcome to our special winter edition of InDEPTH. We wanted to catch a bit of the local lockdown diving spirit—no warm water travel diving here. So we reached out to some of our obsessive, warm-blooded diving friends and colleagues to break the ice. Here’s what they shared.

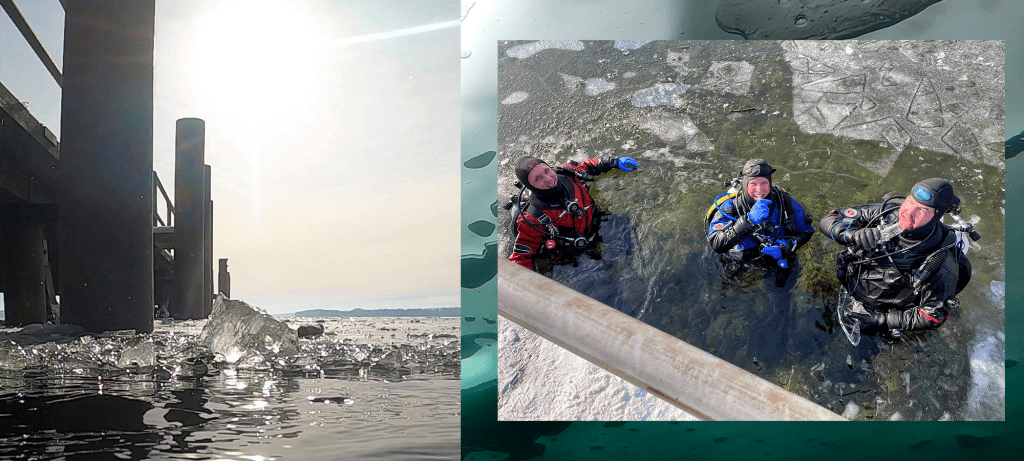

Lake Michigan, USA

“I’m used to ice diving in February. Over the past few years, it’s been in Antarctica, but that wasn’t an option this year. The good news: I landed a photoshoot with Seiko to dive their new Ice Diver Watch and so we obviously needed ice and headed to Michigan. Luckily temperatures plummeted in late January and the inland lakes were nicely frozen over with more than a foot of ice! It was really cold, in fact the air temperatures were colder than the water so we stayed under for 85 minute dives. I think it’s magical to cut that hole and slip below the cold, white world into a completely different place. I’m always mesmerized by the clear ice and the bubbles trapped in it. Our project was successful and the ice conditions were fantastic!“—Becky Kagan Schott

Top: David Schott under ice, photo by Becky Kagan Schott. Bottom: Becky Kagan Schott with watch under ice, photo by David Schott. Guys, get a photo studio!

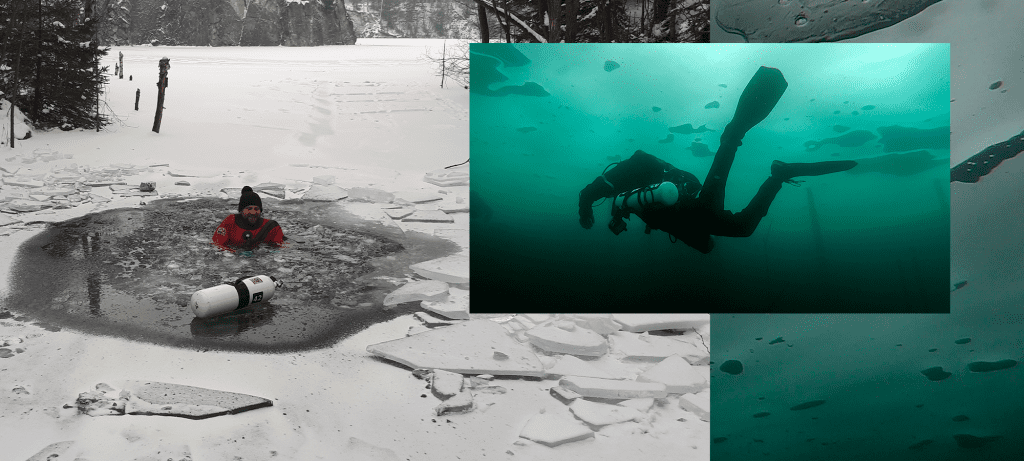

Morrison’s Quarry, Ottawa, Canada

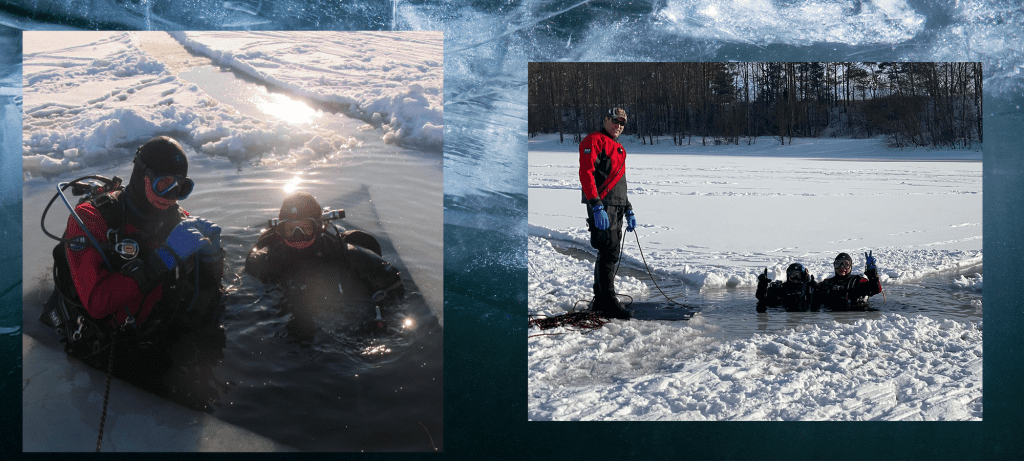

We’ve been diving under the ice since 2008, fast forward to this year and some of the faces have changed, and some of our equipment, but we are still ice diving, taking photos, and enjoying the beautiful viz. We ice dive at the quarry just located just north of downtown Ottawa. The visibility is easily 30 m/100 ft. You cannot silt it out, and the temperature rarely goes below 3ºC/37ºF. Toasty!

As much fun as we have, we do take our diving seriously, and make sure that we follow safe diving protocols. Anyone that joins us must have overhead training for starts. We use cave diving protocols, and we are not tethered. We use a reel, and always have a continuous line to the surface.

We put an ice screw into the surface of the ice, where we attach our reel, then go to get geared up. There is a nice, stove-heated cottage at the quarry, that makes getting changed much more comfortable. Each team goes to the water together, and gear checks are done without breathing the regulators. This is the absolute last thing we do, before descending, to avoid a regulator free-flow. The leader takes the reel, and we submerge into the blue abyss.

Once below, we practice bottle rotations, bottle and scooter drops, valve drills, s-drills, disconnecting inflators, taking photos, and even just hovering, or looking for the resident turtle. Once in a while, you may see a fish. [Ed. Note: The GUE way—practice, practice, practice!]

Upon our return to the opening, we immediately undo our harness buckles and drysuit inflation hoses to beat the freeze. One thing NOT to do, is to partially unzip your drysuit zipper. I made that mistake once, thinking I was quite clever getting my zipper started. It proved to be exactly the opposite of clever. The zipper froze, and being half open, I could not jump back into the water to thaw it. I sat in a heated van for what seemed like an eternity, waiting for my zipper to thaw, so that I could unzip it. You will only make that mistake once!—Chan Blanchard

Photos courtesy of Chantelle Blanchard

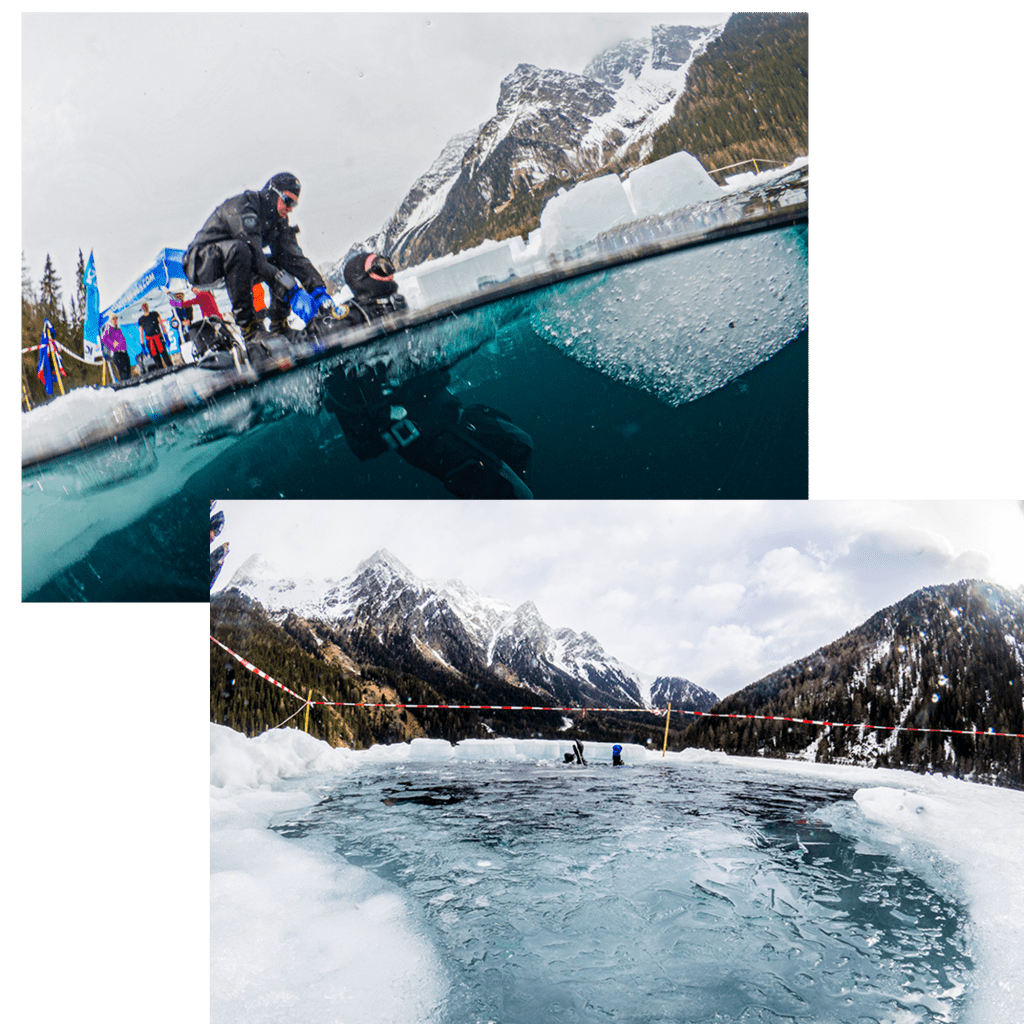

Borek Quarry, Southeast of Prague, Czech Republic

Not having any luck reaching Divesoft’s Jakub Slama by email? Chances are he is partaking in some water time at the local quarry, testing gear. This in the dead of winter. Slama calls it a “A nice day away from emails!”

“On this particular day we went to test gear at Borek Quarry, which is a popular place popular for fun dives and training, located about 1.5 hours SE of Prague in a small valley and covered with about 15cm/0.5 ft of snow. It’s about 33m/110 ft deep with water temperature at its lowest at 4ºC/39ºF. The air temperature was -10ºC, so a little chilly. The testing crew consisted of the J3 Team; Jakub Hecko, one of Divesoft software programmers, Jakub Šimanek, the factory instructor trainer and myself, Jakub Slama the sales guy.

We packed up the van with gear and the list of tasks and headed for the quarry. After opening the boom gate, we put our snow chains on the van and drove right down to the water. There was about 5cm/2 in. of ice completely covering the quarry; too thick to break without tools. We cut the ice with a chainsaw at a place shallow enough to climb out of the ice, which is quite handy, especially with a gear on.

We were testing a new remote display, which is nearing completion. I was also testing a new configuration of Divesoft’s Liberty rebreather called the “Heavy,” [A GUE-configured CCR] after we made some changes. [Ed.—He’s Not Heavy, He’s My (GUE) brother??] All of us were diving rebreathers with plenty of bailout, as direct ascent to the surface was not possible. Visibility was about 15m/50ft and deteriorated to about 6-8m/20-30ft on the bottom. We ran our reels all the way.

The dive took about 75 minutes including a short deco. I was the only one without a heated dry suit. The boys were toasty. After getting out of the water, you have to get your gear in the van quickly, otherwise everything freezes together, especially fabric and concrete. We headed back to write up our test reports. It was a nice test day, away from emails.”—Jakub Slama

Photo courtesy of Jakub Slama. Background image by Michela Di Paola Photography.

Quebec, Canada

We asked Nath Lasselin, who is an award-winning filmmaker, producer and arctic diving expedition leader to share her love of the ice. Here’s what she sent. Wow!

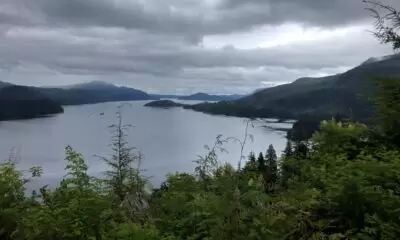

Rabbit Lake in the Chugach Front Range, Alaska

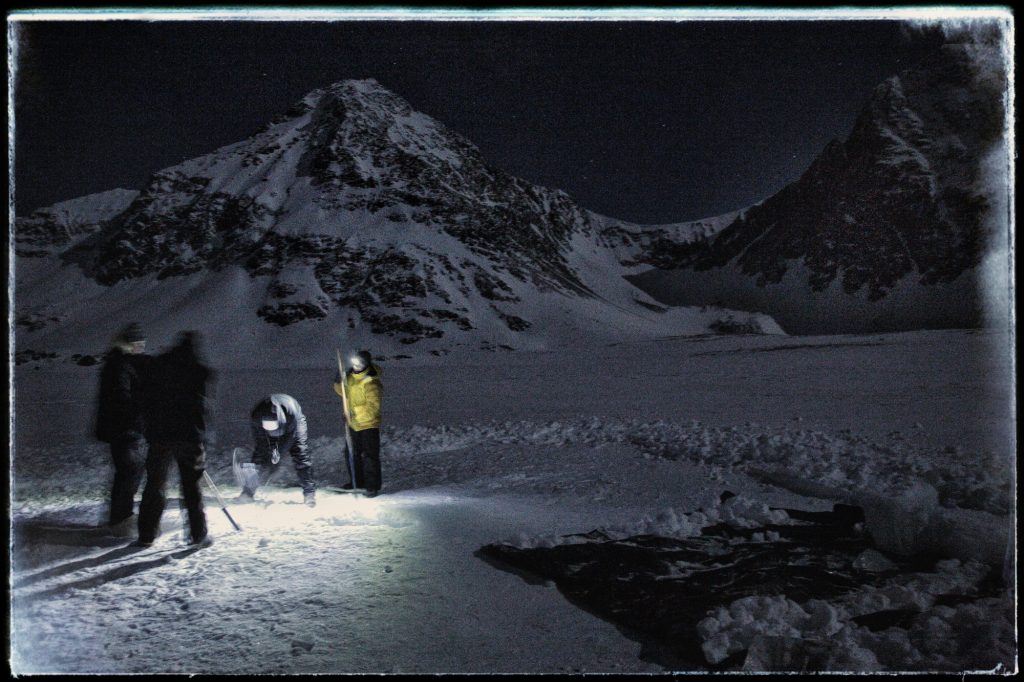

Definition: Type 2 Fun is loosely defined as something that is typically misery in the moment, but fun in retrospect. Backcountry, alpine, winter ice freediving falls squarely in the category of Type 2 Fun.

“This January, with surface temperatures plunging to -20°F/-29ºC, a group of local freedivers loaded up expedition sleds with winter mountaineering equipment, freediving gear, pole saws for cutting through the ice, and contingency gear, and set out towards Rabbit Lake—a remote, alpine lake over six miles into the Alaskan backcountry. Local freediving has experienced a huge surge in popularity, due largely to the COVID-19 pandemic. With various degrees of business restrictions, many local divers have turned to more creative, adaptable methods of exploring underwater.

In the summer, the Lake boasts 100 ft/30m plus visibility, but even in July the water is 42ºF/6ºC; in January, once you get past the ice, it’s 33ºF/0.6ºC. Divers wore 7mm open cell apnea wetsuits. In many cases, these suits are actually warmer than dry suits when floating on the surface, and keep you almost entirely dry prior to submerging. In this instance, it was obviously crucial; not only for comfort—or as close to comfort as you can get when ice is forming on the inside of your mask—but also for safety.

Normally, experienced freedivers in attendance have breath-hold times ranging from four-to-six minutes. However, between the cold, the caloric burn from hiking, climbing, and cutting through almost four feet of solid ice by hand, divers were happy with 90-second holds per dive. And while we’ve pushed past 30m/100ft deep in Rabbit Lake in the summer, on this trip, illuminated by 15,000 lumen video lights, divers stayed within 10m/33 ft of the surface, using a weighted line to find their way back to hole, like a cave diver running a reel.

Any expedition needs support, and especially on trips like this including; support personnel, cohesive teams, careful planning, and proper equipment. These underscore the difference between Type 2 Fun and accidents. In many ways, we use these trips as an opportunity to practice and execute extremely challenging projects safely. The procedures and methods are saved for future projects and refined and improved as needed.—Ron Fancher

Photos courtesy of Dive Alaska, Jordan Flesner, Jarod Powell, Frank Marley, and Alex Fancher

Shiretoko National Park in Northern Hokkaido, Japan

Our friends at Fourth Element know all about ICE, or rather counteracting its effects. A few seasons ago, the enterprising British thermal purveyors hosted Expedition ICE—a dive trip to Shiretoko National Park to photograph the elusive free swimming Sea Angels aka Clione limacina. Of course they used the opportunity to test their new non-electric X-Core heating vest, which allowed for some extended dive times. Isn’t that what diving is all about? More depth, more time.

Top Photo by Charlie Jung. Expedition photos courtesy of Fourth Element.

Vladivostok, Russia

Welcome to the seventh-annual World Under Ice Dive Games, held this year in snow and ice-laden Vladivostok, despite COVID-19 restrictions. The event was sponsored by DAN Europe, the National Dive League, the Russian Geographical Society, and Frogman drysuits. This year 30 intrepid heat-challenged divers from Russia, Korea, Egypt, Italy and Cyprus braved the cold to compete on the special underwater course beneath the ice. Using their compass and a map, divers navigated the course according to their instructions and earned points by performing certain tasks along the way, while on the clock. The winners were treated to warm fuzzies! [Ed—We made that last part up] See you at Vladivostok next year. Don’t say Nyet!—Sergei Cherepanov

Photos courtesy of the Sea Frog Dive Club. DAN Europe banner art by Russian cartoonist Sergey Cherepanov, Instagram @seniorcartooner.

Lake Lison, Switzerland

“Our tradition is to go ice diving for one big weekend at the end of every winter with a group of friends. We chose this lake because the visibility is usually very good and we hoped to get some good shots. The air temp was 5ºC but the water was only 2ºC. It was freezing! Because of the cold, we kept dives to 20-30 min. What’s more, the regulators went freezing when we jumped. It definitely made valve drills challenging!—Christelle Baudat

Photos by Gatien Cosendey.

Lower Saxony, Northern Germany

“My buddies Antonia and Christian and I dived in a dredging lake, which has a maximum depth of 18m. The air was -6ºC/21ºF and the water 3ºC/37ºF. I was wearing my heated Santi vest beneath my DIR gear and we used a 50m/165 ft leash and a 2m/7ft buddy-leash for safety. It was my first time sawing a hole in the ice, which definitely warmed me up. Of course, my dog was very curious and found the ice hole intriguing. I had to make sure she didn’t fall in. We’re still learning ice diving and think it would be sensational to go ice diving in Greenland”—Claudia Lindner

Photos courtesy of Claudia Lindner. Background image by Michela Di Paola Photography.

Gullmarsfjorden in Lysekil, Sweden

“Gullmarsfjorden is a popular place for Scandinavian divers to visit. We refer to it as “green water diving.” Fortunately, the winter opens a whole other type of diving for our group who would like to see something different. Our adventure took place in January, which is typically mild. My buddy Erik and I decided to go diving on a sunny day to get some nice ambient light for a multicolor shallow water photo. Fortunately, the temperature outside has been below freezing for over a week and the ice only covered the confined areas in the harbor, so no hole cutting was needed. The beginning of the dive was the worst, as your face hits the 0°C/32ºF water. But it went numb after a few minutes and was no longer a bother. We tied a reel to our entry point right where the ice started and used it the whole dive. Unfortunately, the fish life is not what it is during summer, many divers look for nudibranchs and squids instead.”—Jesper Haav

Photo courtesy of Jesper Haav.

Lake Plöenersee, Germany

“The opportunity to ice dive in Germany is limited. The cold periods are usually not long and hard enough for the lakes to freeze over. But this February was perfect! We were the first ones at the lake in the morning and sawed our way into the water. Hard work for hard men! With water temperature of 3ºC/37F and a frosty -15ºC/5ºF in the air, we had to prepare our equipment especially carefully.

We had an “encounter of a different kind” when ice sportsmen met above and below the water. We were diving in the shallow area in a small indentation of the lake. Some ice skaters were having fun there, too. We could see them dimly! They were making their circles above us and we could hear their scratching on the ice booming loudly in our ears. It was a surreal experience!

Unfortunately, even ice dives are limited by gas supply and eventually must come to an end. In retrospect I should have hurried from the lake to the car! The zipper on my drysuit iced up in the frosty air. I had warm water in the car, but it was closed. And the key was? In my suit of course!”—Keith Kreitner

Photos courtesy of Keith Kreitner. Background image by Michela Di Paola Photography.

Lake Palù, Chiesa Valmalenco, Italy

“My dive in Lake Palù will always remain in my memories. The air temperature was 0ºC/32ºF degrees while the water temperature was 2ºC/36ºF. The episode that I will never forget relates to my regulator. I was ready to jump into the water only to discover that my regulator was completely frozen and it was not possible to breathe! In order to make the dive, I dipped it in a pot of boiling water, put it in my mouth and immediately submerged under the ice! It was a short dive and not very deep. Thanks to the Valtellina sub DIVE club for making it a wonderful experience!—Michael Forenzi

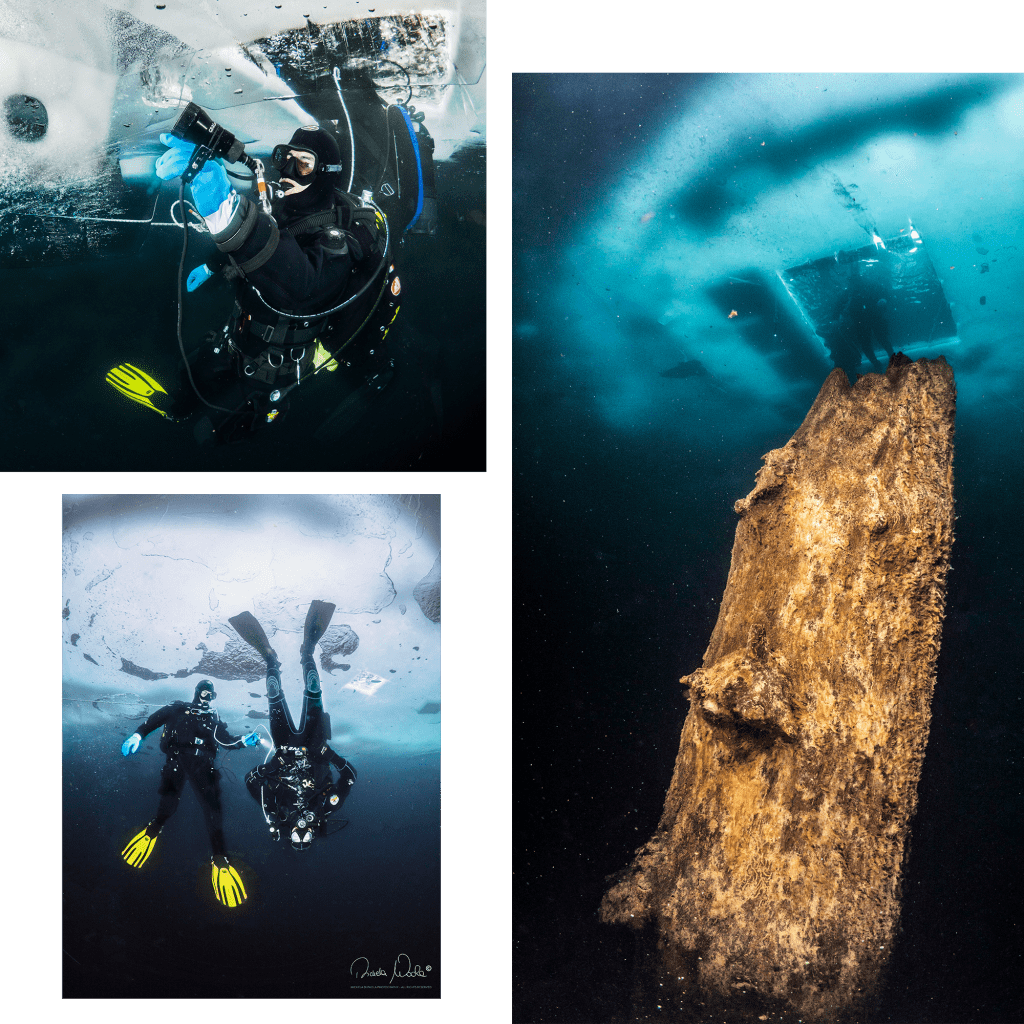

Anterselva, Italy

“There is no shortage of locations for the cold winters of the Alps. But in Anterselva in the northeast it is special! A small alpine lake at 1650m/5,414 ft completely surrounded by mountains of more than 3000m/9,843 ft. The lake was formed thousands of years ago, after a landslide blocked the path of the stream that flows downstream. In fact, on the bottom we can still admire huge fossil trees, which were part of the forest that once covered the valley floor. Ice is always very thick at this altitude. From 60 to 90 cm/2-3 ft and it is not easy to cut with a chainsaw. At night the temperatures drop to -15°C/ 5ºF, but during the day it is a few degrees above zero. We found a fossil tree, still standing, after who knows how many hundreds of years! It has a huge diameter; the two of us could not surround it with our arms. As soon as we touched it, the sediment clinging to its surface was released, ruining the visibility.”— Matteo de Lorenzi

“Time simply stops underwater, there is only you with your buddies; and you are there impressed by the landscapes and wonderful phenomena that Mother Nature offers you.”– Michela Di Paola

“My heart’s beats slow down, my breathing rate becomes normal, I don’t feel the chill anymore and I’m almost astonished observing the wonderful spectacle in front of me; the world seems upside down.”—Michela Di Paola

“I lift my head up and admire the air bubbles that, coming out from my regulator, go up towards the ice surface upon us and run away, (more or less fast), in different directions, glittering and reflecting many colours creating a magic game of lights and shadows. It generates emotions that are more than words can say, and will remain unforgettable.”—Michela Di Paola

Images by Michela Di Paola Photography. Grazie to Niccolò Crespi for his help with this story.

Undisclosed Lake, Finland

“Around January to March most of the lakes and quarries in Finland have ice cover and the sun is quite low so the water gets very clear because it’s cold and there is no photosynthesis. During these times the water below 6m/20ft is around 4ºC/, but shallower than that the water is closer to freezing.

One ice diving specific safety issue is free flowing regulators and freezing inflators. You learn to be very quick disconnecting your inflator LP hoses.

My personal record is seven times during an ice dive. Because the water is coldest near the surface and the freezing happens usually at the surface or just below, one tip is to start the dive just using your drysuit until you hit 6m/20ft where water starts to get warmer. Another is to add some silicone to the inside of your inflator to prevent it from freezing, and do your regulator check underwater not at the surface to prevent freezing. Lastly, I can tell you that a warm beverage tastes very good after nice long ice dive.”— Teppo Lallukka

Photo courtesy of Teppo Lallukka

Antarctica

We can’t mention ice, without giving a shout out to the Queen of Ice Adventures, our friend Faith Ortins, founder and principal of Blue Green Expeditions.

“Diving around icebergs in polar waters is a different kind of challenge. While there is less risk of an overhead environment, there are other issues that are unique to this type of diving. First, it is important to remember that these icebergs are large sources of fresh water gradually mixing with the salt water ocean they are sitting in. That means there is usually a layer of relatively fresh water around the iceberg creating a vertical halocline of variable width. Unlike haloclines sometimes found in caves, this halocline is usually impossible to see as it is the same temperature of water as the sea water. As a result, it is common for neutrally buoyant divers to swim into a fresh water layer and find themselves sinking rapidly. Of course, they respond by adding air to their BC or swimming upward only to exit the fresh water and begin rising very quickly. And the yo-yo effect begins. This takes some getting used to even for experienced divers. However, those with good drysuit skills will adjust quickly.

The second issue is that this iceberg environment is generally much more dynamic. The polar dive guides are very good at selecting icebergs that are stable due to either their size and shape or being grounded on the bottom. However, the weather conditions are very prone to changing, and of course, the icebergs themselves are constantly as they melt. It is critical that divers have excellent situational awareness skills. They must watch for changes in the ice in the event the iceberg begins moving which could lead to the diver being trapped under the ice very suddenly. Even a small piece of ice breaking off from the lower part of the iceberg could knock a diver unconscious if hit when the ice floats up to the surface. Reading the ice is an important skill for diving around icebergs and the knowledge of the polar dive guides is paramount. It is also one of the most fun dives ever. Well worth braving the freezing polar waters.”—Faith Ortins

Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) has teamed with Ortins and her team to provide two unique diving trips to Antarctica in January and February, 2022 and spaces are still available. Need further encouragement? Here GUE founder & president Jarrod Jablonski quizzes Faith about the coming expeditions. Keep the Faith! And stay warm people—go talk to Mr. Standing!

Dive Deeper:

Check out Nico Lurot’s Top Ten Ice Diving Locations in The World on GUE’s YouTube channel. And for God sake’s stay warm!!! ;-D