Community

Is a Just Culture needed to support learning from near misses and diving accidents?

Human factors coach Gareth Lock delves deep into the meaning, impact, and need for “Just Culture” in diving, as well as creating a psychologically-safe environment that enables divers to highlight and challenge possible safety issues. Lock argues that both are essential, and offers practical suggestions for building the culture we deserve.

Text and photos courtesy of Gareth Lock

The heavily regulated aviation industry is often praised for its effective Just Culture, which has facilitated an ultra-safe operating environment. What purpose could a Just Culture serve in diving, and why should we care when we are in an unregulated environment? Aviation is ultra-safe—regulatory agencies implement safety targets and demand continuous improvement of safety performance. Nevertheless, adverse events still happen. Why? Because of the complex nature of operations and the variability of human performance. It isn’t because of ‘stupid pilots’ and/or ‘pilot error.’

The following two stories centre around a similar adverse event—a departure from a point on the runway the crew weren’t expecting—but have very different outcomes when it comes to the opportunities to learn and improve. As you read them, consider which one has more parallels with diving and the diving community.

Case #1

A crew of four pilots taxi out at night to depart from Miami, Florida to Doha, Qatar on a Boeing 777 with 279 people onboard. Due to busy radio communications and an internal misunderstanding as they navigated around the airfield at night, the crew mistakenly entered a runway at a point that was further from the departure end than their performance planning assumed. This meant that the runway distance available to them was 2,610 m/8,563 ft instead of 3,610 m/11,844 ft. The crew had not noticed this problem before they asked for departure clearance.

After they received departure clearance, they accelerated down the runway to reach take-off speed. Very shortly after the crew ‘rotated’ (pulled back on the stick), the aircraft struck the approach lights of the opposite runway, causing damage including puncturing the skin of the aircraft. Fortunately, the puncture did not breach the pressure hull. The crew were unaware of the impact and carried on their flight to Doha without any further issues. On arrival, while taxiing in, the ground crew noticed the damage and informed the flight crew.

This event was widely reported in the media. It was also investigated internally and by local aviation authorities. The CEO’s response was, “We will not accept any kind of lapses by pilots because they have hundreds of passengers whom they risked,” and all four pilots were fired. Scarily, and I believe falsely, he also stated that “At no time was the aircraft or the passengers put in any harm’s way.” However, the aircraft was still on the ground when it left the runway, and if the crew had to abort their take-off just before rotate speed, the aircraft would have likely gone off the end of the runway and into the waterway—and probably the housing estate outside the airfield perimeter—with the loss of the aircraft and possibly passengers and crew.

Case #2

The flight crew were operating from a Caribbean island with a single runway after they had arrived the night before as passengers. Neither the Captain nor the First Officer had been there before. They boarded their aircraft in the dark just before their passengers arrived. Once everyone was onboard, they left the parking area via the single entrance to the runway, and they turned to go to their departure end. The airport diagram they were using for navigation showed a single large concrete turning circle at the end of the runway. As they taxied down to where they thought the end was, they came across a large concrete circle and so started their turnaround process to line up facing the other way to depart.

They gained departure clearance and started to accelerate down the runway to reach their rotational speed. After rotating, they noticed that the lights at the other end of the runway passed under them more quickly than they expected for a runway of this length.

Once they arrived back in the UK, independently, both the Captain and First Officer looked online at Google Earth as they had an uneasy feeling about what had happened. What they found was that there were two concrete circles on the runway and not just the one as marked on their taxi diagram.

They immediately got a hold of their dispatch team and let them know that the airport diagram they had operated with wasn’t accurate and could cause a major problem. They also raised an Air Safety Report (ASR) within their airline so others could learn from the circumstances. The crew were congratulated for reporting this event, even though their departure safety margins had been reduced. The charts were amended as a consequence.

Given that pilots are reported to make between three to six errors per hour, which airline would you rather operate with—the one that welcomes and congratulates its operators for reporting mistakes, or the one that punishes them? Furthermore, how important do you think the perception (or illusion) of safety is for the first airline’s customer base? The absence of reported near misses, incidents or accidents does not mean that your system is safe. Paradoxically, those organisations who report more and learn from those reports have fewer adverse events, especially repeat events.

What is a Just Culture?

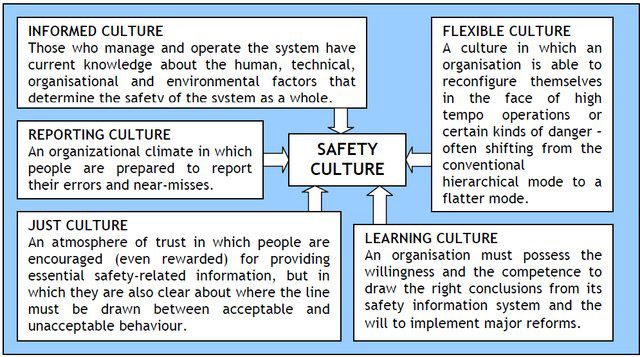

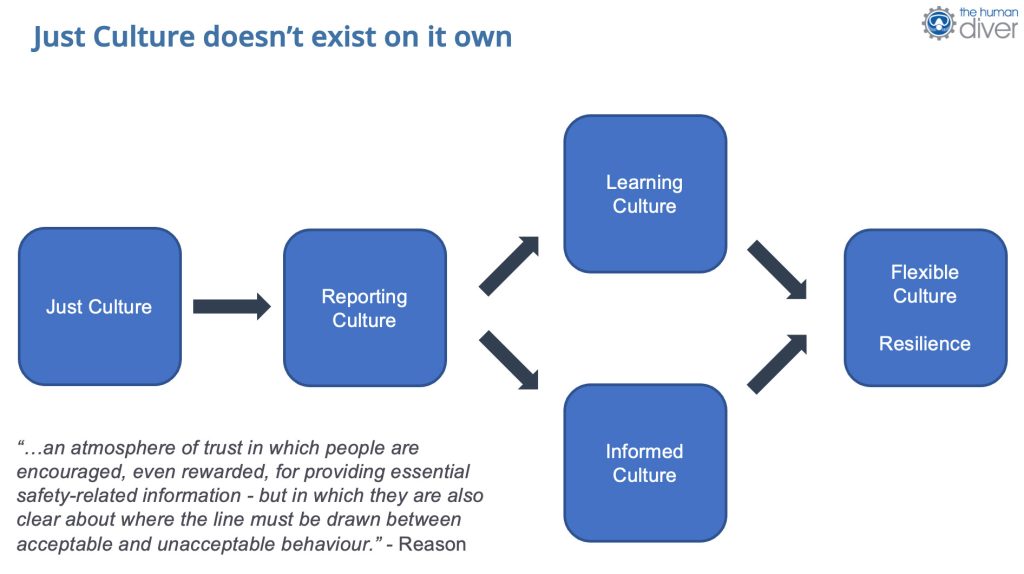

A Just Culture was originally mentioned in 1997 as part of James Reason’s work in Managing the Risk of Organisational Accidents where he describes it as being part of a Safety Culture. There were five sub-cultures that made up a safety culture: just culture, reporting culture, informed culture, flexible culture, and a learning culture. The image below shows their interaction in more detail. My personal view is that Just Culture supports everything else, but it could be argued that if you don’t have a Reporting Culture, you don’t need a Just Culture.

Reason recognised that a wholly Just Culture is unattainable, but that there needs to be some line between errors or unwanted outcomes caused by system design and human performance variability, and those caused by gross negligence, sabotage, or reckless behaviour. As he highlights, “The difficulty is discriminating between these few truly ‘bad apples’ and the vast majority of unsafe acts to which the attribution of blame is neither appropriate nor useful.” Sidney Dekker, author of Just Culture goes further and says, “It isn’t so much where the line is drawn, but who draws it.” In the world of diving, it is often online peers or the lawyers who draw the line. The former rarely have the full context and don’t understand human error and human factors, and the latter aren’t necessarily interested in wider organisational learning, as they are focused on their claim.

What does a Just Culture do?

A Just Culture facilitates the sharing of conditions or outcomes which aren’t expected or wanted—e.g., near misses, incidents, and accidents. The sharing happens because there is a recognition and acceptance within the team, organisation, or sector that human errors are part of normal operations and that professionals come to work to do a good job in spite of the limitations and constraints which are part of their job. These limitations and constraints create tensions and conflicts between doing what is written in manuals and procedures (Work as Imagined) and what really happens (Work as Done) to achieve the results for which they are being rewarded (e.g., productivity goals). Sometimes it isn’t possible to complete the job by following the rules because of these conflicts—conflicts which often have commercial drivers as their source. For example, pilots might not be able to do all their pre-departure checks in the correct order and at the right time because of limited ground time on turnarounds. For the aircrew, this can be business as usual, but in the event of an accident investigation, this would be picked up as deviant behaviour.

This is like dive centres who are commercially driven and face local competition. They would like to up their productivity (to make up for reduced costs), but this means that standards might be bent every now and again to make things work. This could mean diving deeper than maximum depths to make use of boats for multiple clients and/or courses, not completing the minimum dive time or the minimum number of dives which increases instructor availability, increasing the number of students in a class to maximise revenue or deal with a shortage of instructors/DMs, or not having surface cover when needed because they couldn’t be sourced or they cost too much to include in the course fees. There is also the very real issue that some standards are not valid or that organisations accept unauthorised protocol changes but don’t do anything about that.

Proceduralising a Culture? Isn’t that an Oxymoron?

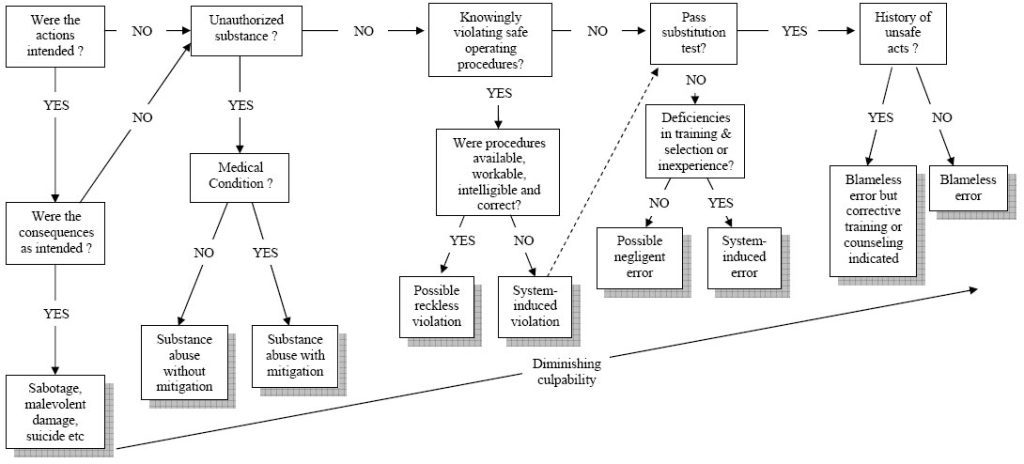

Understanding this context is not easy, so part of Reason’s initial work was the production of a flow-diagram or process which showed managers how they could look at an event and determine where culpability might lie and how it should be dealt with. This framework has been reproduced by multiple different organisations like Shell, the Keil Centre, and Baines Simmons.

Each of these processes is a decision tree, with the outcome determining what sort of action should be taken against the individual—sometimes it is punitive. On the surface, this sounds like a good idea. The problem is that these processes rarely consider the rich context that is needed to understand how it made sense for someone to do what they did, with biases like hindsight, outcome bias, severity bias, and the fundamental attribution bias getting in the way of understanding what really happened. This often leads to punishment when it is not applicable. Furthermore, which of the many individual contributory or causal factors do you examine as part of this ‘process?’ Most of the time, the focus is on the ‘sharp end’—those doing the work, rather than further up the organisational chain and the conditions.

Some organisations have inserted two additional tests to help managers determine if this was an individual problem or a systemic one. The substitution test asks if someone with the same knowledge, skills, and experience, and under the same pressures and drivers, but without knowledge of the outcome, would do the same thing. If they would, then it is likely a system issue. The other test concerns whether this event/action has happened before to either the organisation or to the individual. In both cases, if it has, then it highlights organisational weakness either in system design or training/coaching of the individual after the first (or subsequent) event.

The problem with such process-based approaches is that they can’t create a culture, therefore they can’t be part of a Just Culture. Fundamentally, a culture can’t be proceduralised—a culture is based on the relationships and interactions between individuals of a group, team, organisation, sector, or nation. Ultimately, it is ‘how things are done around here,’ often without those involved knowing why! We love technology to make things easier, but in this case, a process flow chart doesn’t help create a Just Culture.

Build the organisational learning into the investigation process

Things have changed in some organisations though. BP decided to review and rewrite their Just Culture process because they realised it wasn’t working as intended—the goal of the policy was to facilitate learning from near-misses, incidents, and accidents, but they were missing too much. Their rework meant that they asked learning-focused questions as part of their investigation process. Rather than asking the Just Culture questions at the end, in isolation and with limited information, they required the investigators to ask the questions during the investigation to generate the rich context needed to understand the event. Consequently, they found that 90% of their incidents were systemic in nature and were not caused by human error of those operating at the sharp end. You can see an extract from their investigation flow-diagram below. While this is a process, the purpose is to facilitate discussion and learning during the investigation rather than using an isolated judgement at the end.

Does diving need a Just Culture?

The simple answer is yes. It also needs a psychologically-safe environment. In my opinion, psychological safety is needed before an event to allow latent conditions to be highlighted and challenged, whereas a Just Culture is needed after an event to allow discussions to take place around the context and how it occurred. Psychological safety supports the discussions under a Just Culture.

The diving community needs a culture that follows those same initial concepts from James Reason in 1997, the recognition that errors are normal, that the skills and experience of those involved within the current operating environment must be considered, and that only when gross negligence or sabotage are present should we look at punitive action. This means that when adverse events occur in diving and they are not subject to legal action, then the events should be used for learning. Unfortunately, the legal systems do not currently address the needs of a Just Culture because the goal is to find someone or some organisation to blame and which will facilitate damage claims. In my opinion, this poses a problem in the US where litigation is rife, particularly in diving, often for minor events. Unfortunately, in some cases, litigation is the only way to get some form of damages, or even an apology.

Diving learning from Healthcare and Wildland Firefighting?

Fortunately, it doesn’t have to be that way. Following a discussion with a colleague at Lund University, Sweden where I am currently studying for a MSc in Human Factors and System Safety, I was told that there are hundreds of hospitals in the USA who have made inroads into reducing litigation claims and increasing patient safety by undertaking Communication and Resolution Programmes (CRPs). These CRPs have reduced litigation, increased individual and organisational learning, increased patient safety, and, ultimately, have reduced insurance premiums because problems are resolved in a different manner. These programmes are based around a common understanding of human error, performance-shaping factors, and a Just Culture. Fundamentally, if you don’t understand human error, then you can’t create a Just Culture. Regarding Wildland Firefighting, I have previously written on that in InDepth.

In the sports diving sector, we don’t have a standardised, structured investigation process which is based around learning with most investigations looking at proximal causes rather than systemic ones, and often looking for blame. Even in the commercial sector, the HSE and OSHA are focused on non-compliance rather than learning opportunities. This means that building the ‘Just Culture’ questions into the learning process isn’t possible (at the moment). However, as a culture is based on the relationships and interactions between those within a team, organisation, or sector and the language they use, we can certainly start to develop one by changing the language we use to facilitate the sharing of, and learning from, near misses and incidents/accidents. Producing documentaries like ‘If Only…’ is a great way to get the concepts across by telling a story, and stories are how we learn.

I know of one GUE community who have set up their own ‘Learning Forum’ on Facebook which allows the open, critiquing (but not critical) discussion of adverse events and near misses—a forum I support. The Human Diver: Human Factors in Diving Facebook group also supports a learning-based approach with very mature conversations taking place when adverse events are discussed.

How can you help build this culture?

Start by being curious and limiting your judgments. While it is hard, try not to fall foul of the cognitive biases that I mentioned earlier, ask the simple question, “How did it make sense for them to do what they did?”, and you might be surprised at the answers you get back. Asking “How?” moves the focus to the context; “Why?” and ‘“Who?” are all about the person which invokes a blame response. At the organisational level, asking the same questions can highlight gaps in your own processes, procedures, expectations, and leadership. If instructors are consistently breaching standards, is it because the standard is unachievable or does not add the value you think it does to the operation? Firing them without understanding why they breached the standard is an example of a failed Just Culture. It can be uncomfortable to ask this question, but asking it is essential for improvement. Plus, in this scenario, you don’t need an accident to create learning because the latent conditions are already present. All you need is a genuine curiosity and a desire to learn and improve.

Dive Deeper:

Human Diver: They broke the rules! So…?

InDEPTH: Human Factors page

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 450 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture.