Community

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: The Power of Context-Rich “Second” Stories

Proper storytelling is a key to learning from the mistakes of others. Human Factors consultant and educator Gareth Lock explains the power of context-rich stories to inform and help us to develop the non-technical skills needed to make better decisions, communicate more clearly, and lead/teach more effectively.

by Gareth Lock

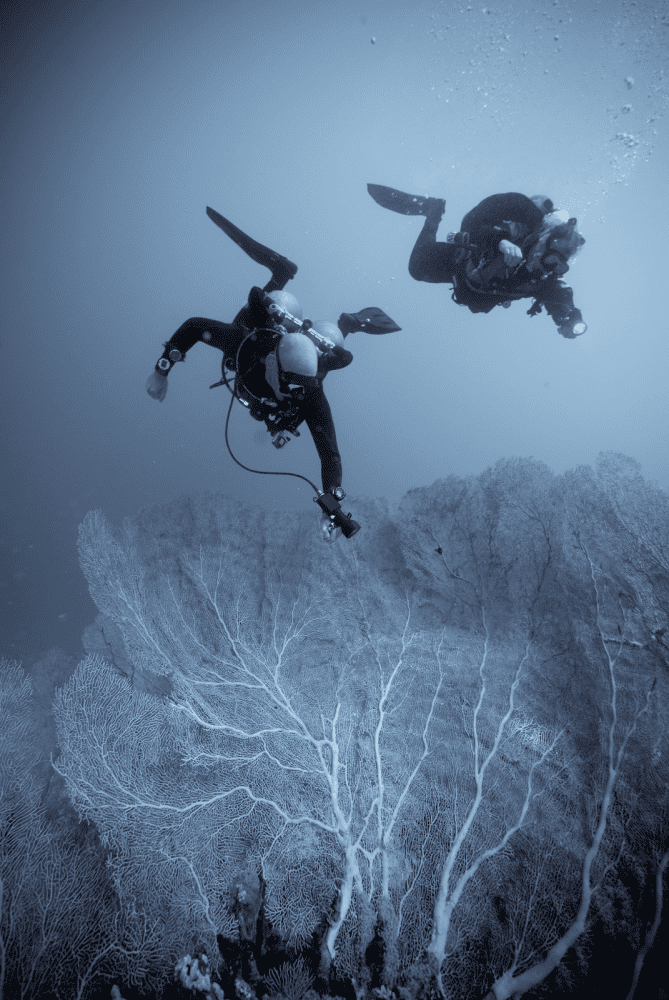

Header image courtesy of Gareth Lock. Divers from Red Sea Explorers’ examining a magnificent gorgonian coral.

Diving can be a fun, sociable, and peaceful activity; it can be challenging and technically difficult; and it can be a way of escaping the hustle and bustle of modern life. Sometimes new wrecks are discovered, caves have new line laid in them, new encounters with wildlife are experienced, and in many cases, courses are completed where both instructors and students have learned something new.

However, it can also be scary, harrowing and frightening if things don’t go to plan or if the plan was flawed in the first place.

Fortunately, the majority of dives which take place are the former and we consider the outcomes to be positive. If we think about it, the goal for every dive should be to surface, having had an enjoyable time, with gas reserves intact and no-one feeling physically or emotionally injured. But how do we achieve this goal considering the inherent risks we face while diving?

The easy answer would be to have effective training, to have the correct equipment, and to have and apply the right mindset. These three things together then lead to safe diving practices. You could say that the majority of safe diving practices and safely designed and configured equipment comes from feedback following accidents, incidents, and near misses. You only have to look at the work which the late, famed cave explorer Sheck Exley did in terms of cave diving fatalities and his “Blueprint for Survival” to see how procedures and equipment have evolved.

What do we learn?

There are accident and incident reports available to us. What do we learn from them? Bearing in mind that the majority of reports which divers see are either in social media or summarised in reports like the Divers Alert Network Annual Incident Report or the BS-AC Annual Incident Report.

For example, the following incident reports are written in a style similar to those you would find on social media or in an organization’s incident report.

An inexperienced diver entered the water to provide support for a guided dive to 24m. They got separated from their buddy, made a rapid ascent to the surface after nearly running out of gas. They were recovered on the boat without any symptoms of DCS being present.

A diver on the final dive of a rebreather training course entered the water from a dive boat. The diver swam to the side of the boat to receive their bailout cylinder to clip on. While sorting their gear out alongside the boat, they appeared to go unconscious and descend below the surface. The diver was recovered from 38 m/124 ft and despite CPR and first aid being applied, they were pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital ER. On inspection, the oxygen cylinder on their rebreather was found to be turned off and the controller logs showed that the pO2 had dropped to 0.05 while they were on the surface.

How much learning do you get from these reports? What emotions did you feel while reading them? What did you think was the primary cause of each of these events? If you were to choose two or three words to describe the causes, what would they be?

Human error? Complacency? Inexperience? Rushing? Not paying attention? Overconfidence? Naivety? Arrogance? Stupidity? Who was it? Where was the instructor? Were they certified? Which agency? Were they qualified?

All of these are normal responses, and they make up the first story.

The First Story

The first story is the narrative we hear, and we start to make immediate judgments on. We can’t help making judgments, even when we try not to. We make judgments because we compare the stories we’ve just read or heard to our own previous experiences. We match patterns to what we ‘know’ and then fill in the gaps with what we think happened, all the time thinking about whether it was the ‘right thing’ to do based on our own experiences.

This ‘filling in gaps’ is normal human behavior. Because our brains are constantly trying to make sense of the situation when we don’t have enough information about a scene or a situation, we reflect on what we’ve seen, read, and heard in the past and then make a best guess or closest fit. During this process, we will be subject to a number of biases, and one of the strongest at this stage is called confirmation bias. This is where we think we know the answer to the question, then as we read or hear something in the story that aligns with our reasoning, we stop looking any further because we have confirmed our suspicions.

In many cases, we carry on and don’t think anything of the learning opportunities presented because we know what happened, we know that ‘we wouldn’t do that’ because we would have spotted the issue before it became critical. We often make use of counterfactuals (could have, should have, and would have) to describe how the incident could have been prevented.

Unfortunately, this means that often we don’t learn. There is a difference between a lesson identified and a lesson learned—a lesson learned is where we make a conscious decision to accept how we do things based on the conditions and outcomes, or we actually put something in place which is different than what was there before and see how effective it is to resolve the problem encountered.

If we are to make improvements, we need to look at the errors, mistakes, and deviations that were made. However, we must recognize that errors are outcomes, not causes of adverse events. If we want to stop an adverse event from occurring, we need to look closer at the conditions which led to the error occurring i.e., the error-producing conditions.

The easiest way to look for error-producing conditions in an event that has already happened is to get those involved to tell context-rich stories. This becomes the second story.

The Second Story

Second stories look much deeper than what we first hear. They look at the context, the local rationality, the conditions, especially those conditions which might lead to errors. Ultimately, they expose the inherent weakness and gaps in any system, where the system includes people, paperwork, equipment, relationships, the environment and their interactions.

Second stories also highlight how divers and instructors are constantly adapting and changing their behaviors/actions to deal with the dynamic nature of diving. They describe ‘normal work’. This adaptation could be moving dive sites, increasing or reducing the time for a course, the order in which skills are taught or the amount of gas used/planned for a dive. Second stories describe the difference between ‘Work as Imagined’, which is what is written down, what is expected to happen, and against which compliance is assessed, and ‘Work as Done’ which is what actually happens in the real world and takes into account the pressures, drivers, and constraints which are faced by those on the dive or the course.

The easiest way to see what a second story looks like is to tell it, and the following account is the same recreational event as above but told as a second story.

An Advanced Open Water (AOW) diver with around 50 dives was acting as an ‘assistant’ to the instructor and dive-centre owner on a guided dive with five Open Water (OW) divers and recent graduates from the school they themselves had learned at. The AOW diver felt a social obligation to help the Open Water Scuba Instructor (OWSI) who was leading the dive, because the OWSI had done so much to help her conquer her fear of mask-clearing during her own training. However, she was also wary that, over time, her role had moved from being a diver on the trip to being almost the divemaster by helping other divers out, which she wasn’t trained to do. In addition, the instructor regularly asked her, at the last minute, to help out and change teams to ensure the ‘experience’ dives happened.

On this particular occasion, the AOW diver was buddied with a low-skilled OW diver who acted arrogantly and did not communicate well. In fact, she didn’t believe that three of the five on this trip should have received their OW certificates, given their poor in-water skills. As they approached the dive site, the visibility could be seen to be poor from the boat and the surface conditions weren’t great. The instructor said to the AOW diver, “Don’t lose the divers. I want you at the back shepherding them.”

They entered the water and descended to 24 m/78 ft and made their way in the poor visibility. On two occasions, the OW buddy had to be brought back down by the AOW diver as they ascended out of control. At one point, the OW diver turned around quickly and accidently knocked the AOW diver into the reef. Unfortunately, the AOW diver became entangled in some line there, and the OW diver swam off oblivious to the entanglement. When the five divers and instructor reached the shot-line ready to ascend, the instructor realized the AOW diver was missing. The instructor couldn’t trust the five divers to ascend on their own and didn’t have enough time to wait at the bottom and conduct a search, so the six ascended. On the surface, the buddied OW diver said that the AOW diver had swum off looking at fish in a certain area.

In the meantime, the AOW diver had managed to free herself; but in her panic, while stuck on the bottom, she breathed her gas down to almost zero and had to do a rapid ascent. She surfaced, feeling very scared and sick with panic, just as the instructor was speaking to the other six on the surface. On seeing the AOW diver break the surface, the instructor swam to her but turned and shouted at the other divers, admonishing them for abandoning their buddy on the bottom. The AOW diver felt very alone and wanted to give up diving as she was not given the opportunity to tell her side of the story.

Observations on potential contributory factors and error-producing conditions:

- Deviation of standards on the part of the instructor/dive-center owner taking OW divers to 24 m/78 ft, maybe driven because of the need to generate revenue and offer something unique.

- Authority gradient between the instructor and AOW diver meant that the AOW diver felt they couldn’t end the dive before they even got in the water or once in the water.

- Inferred peer pressure to help out when they weren’t qualified or experienced enough to act in a supervisory role.

- Poor technical skills on the part of the OW divers and the AOW limited their situation awareness to be aware of hazards and risks.

- Limited awareness on the part of the instructor regarding the location of all the divers during the dive.

- Positive note – good decision on the part of the instructor to ascend with the five OW divers in poor conditions and not keep them on the bottom or get them to ascend on their own.

A full account of the second event can be found here where you can also download a guide which contains more detail than the video covers and also gives you details on how to run a learning event at your dive center or in your own classes.

We can see that the learning opportunities have increased in the second stories. They allow certain issues to be identified like time pressures, financial pressures, peer-pressure, authority gradient, teamwork, leadership, decision-making and situation awareness. These aspects are rarely captured or recounted in the narratives we see online or in incident reports. There are a number of reasons:

- They are often considered ‘common sense’,

- Our brains are constantly looking for simple answers to complicated or complex problems, and one of the easiest ways to do this is to find an individual or piece of equipment to ‘blame’ rather than look wider.

- Those involved don’t consider these factors to be important so they don’t write them down.

- Those involved don’t know about these error-producing conditions or human factors so they don’t know to include them.

- There is no formalised and structured investigation process for diving incidents by diving organisations to facilitate the capture, analysis and sharing of second stories.

Telling second stories isn’t enough to create learning though. We have to work out how to change our own behaviors, and that is where the free materials and courses which The Human Diver provides come in. They help develop these non-technical skills in divers, instructors, instructor trainers, and dive center managers/owners to help them make better decisions, communicate more clearly and lead/teach more effectively. Ultimately, it is about having more fun on the dive, and ending each dive with the goal described at the start of this article intact and creating learning in the process.

Since 2011, Gareth has been on a mission to take the human factors and crew resource management lessons learned from his 25 year military aviation career and apply it to diving. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal to bring human factors, non-technical skills and a Just Culture to the diving industry via a number of different online and face-to-face programmes. Since then, he has trained more than 350 divers from across the globe in face-to-face programmes and nearly 1500 people are subscribed to his online micro-class. In March 2019, he published ‘Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors’ which has sold more than 4000 copies and on 20 May 2020, the documentary ‘If Only…’ was released which tells the story of a tragic diving accident through the lens of human factors and a Just Culture. He has presented around the globe at dive shows and conferences to share his passion and knowledge. He has also acted as a subject matter expert on a number of military diving incidents and accidents focusing on the role of human factors.