Diving Safety

Listen Up: Freediving is About to Enter a New Era if Oxama has a Say!

Now, just like their triathlete counterparts, freedivers will be able to access their realtime biometric performance data, including heart rate and blood-oxygen saturation, enabling them to fine-tune their performance, thanks to an Italian start-up called Oxama. What’s more, the device, which links to your smartphone, uses an innovative audio interface, enabling divers to geek out on their metrics, hands-free. Fortunately, adventure writer and photographer Florine Quirion caught up with the Oxama team. Here’s what they had to say.

by Florine Quirion. Header image by Lorenzo Mittiga. Photos and video courtesy of Oxama.

The current tech craze inspires rapid hardware development in many industries, including recreational scuba and tech diving. However, tech innovators have seemed to skip over freediving—until now. In mid 2022, Oxama will introduce an audio freediving computer.

In 2019, Claudio Mattavelli, Massimo Moi, and Vincenzo Palumbo founded Oxama, an Italian start-up. The three passionate freedivers from Milan define their computer as a virtual vocal coach that “tracks your freediving experience.” The team took naming inspiration from blood oxygen saturation (Ox) and the name of pearl divers in Japan (Ama).* They ran a Kickstarter campaign at the end of 2021, gathering 60% more than their initial objective of €15,000.

We met virtually with Massimo, Oxama’s COO, for an exclusive interview following their successful campaign. Let’s dive into how Oxama is going to change the freediving world.

*A quick check with Urban Dictionary paints another picture. Oh those Italians!

Massimo, tell us a bit about yourself… you have been freediving for decades; how did you start, and how has your diving changed over time?

I started freediving at a young age with my dad in Italy in the 1980s. In the Mediterranean Sea, spearfishing is a common tradition, and we used to spend summer vacations spearfishing for hours in the waters of Liguria and Sardinia. We had so much fun that we often lost track of time, even though. At that time, all we had was one mask and two fins.

Later, in the 2010s, I started formal freediving training in a pool. I met Claudio [Mattavelli] and Vincenzo [Palumbo] in 2016 while I was training. The first freediving wrist computers had appeared only a couple of years before, and only recently did that technology get involved in freediving. But despite a handful of brands releasing specialised freediving computers, none of them ever considered biometric data.

How did you come up with the idea for the Oxama freediving computer?

I didn’t have a dramatic wake-up call underwater, but I began to feel a profound desire to improve underwater safety. At the beginning of 2017, Claudio, Vincenzo, and I were preparing for our next summer trip. During our pool training, we realised there should be a way to improve our underwater preparation.

We searched for new exercises that would extend our physical abilities underwater, which led us to conclude that we needed to track how our bodies reacted to these exercises to optimise our results, and the initial idea for Oxama was born. We wanted to better understand the link between our physiological parameters and how long and how deep we could stay underwater. We officially started the Oxama project in 2019. Today, our first version can track eight parameters: heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, head angle, speed, acceleration, depth, and time.

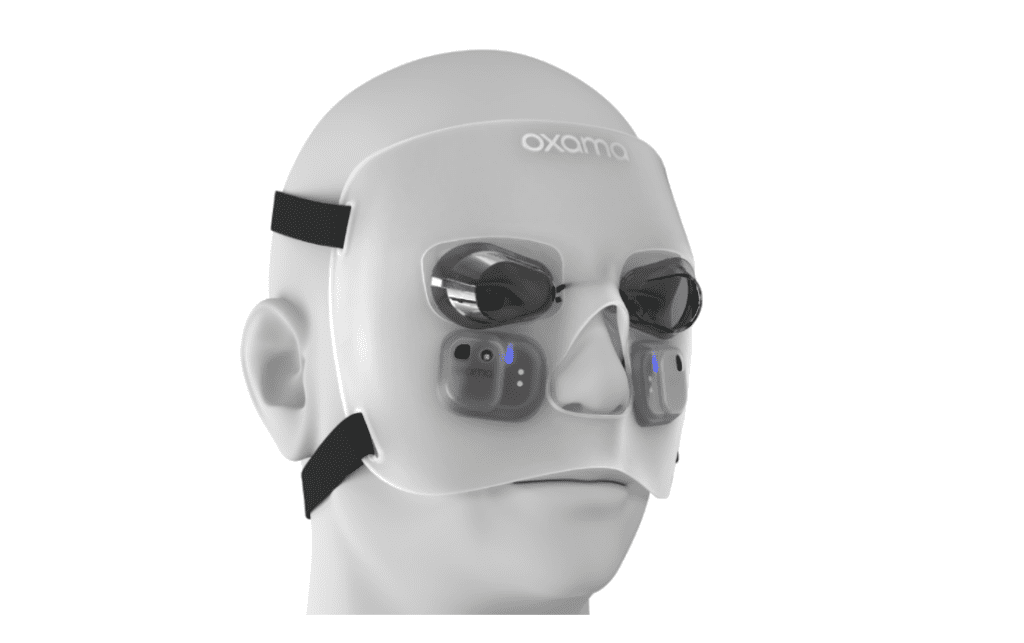

Freedivers wear the Oxama computer on their face—below their mask—allowing them to hear their parameters. Could you explain a bit more about how it works?

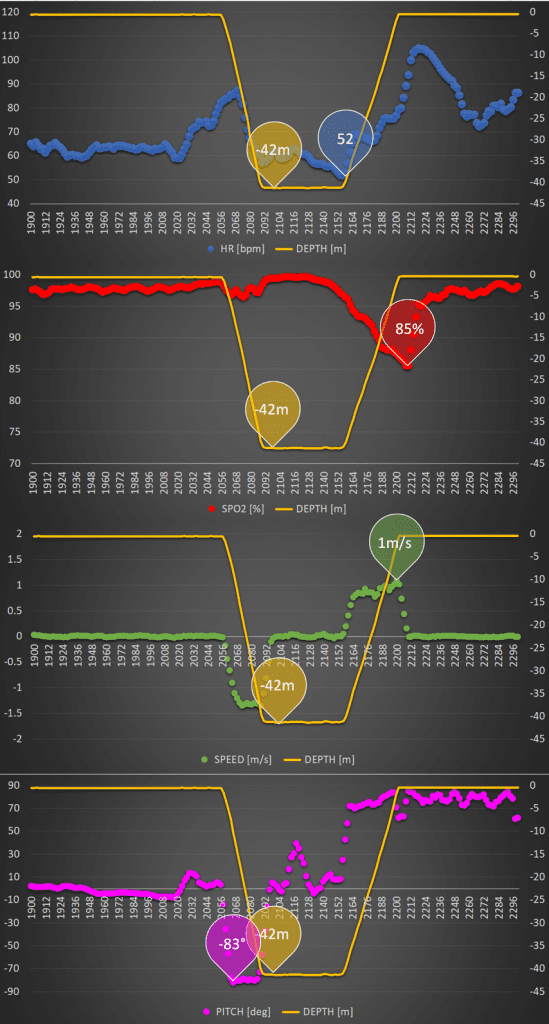

Before the dive, the diver, relaxed, has an heart rate (HR) around 60bpm but during the ventilation it rises up to 90bpm due to the intense respiratory effort. The dive begins and, with a constant speed of -1.3m/s and an almost perfect vertical head posture of -83 degreee, the diver reaches the bottom of the pool at -42m. The HR drops down and, after a static rest of 60 seconds, it reaches the minimum of 52bpm due to the diving reflex. The blood oxygen saturation (Spo2) remained between 97 and 99 % during all the descent, and it starts to decrease when the ascent begins. During the ascent, the speed is about 1.0 m/s, the head posture between 70 and 90 degrees, the HR increases up to 100bpm at the surface. The SpO2 decreases during all the ascent and touches its minimum of 85% as the breath holding end, then quickly increases up to 90% in few seconds as the ventilation starts. In next 30 second, the divers recovers and HR comes back to the basal value of 70bpm and the SpO2 to 99%

The idea is based on bone conduction, which carries sound vibrations through the bones of the skull and inner ear. With audio-based information instead of text on a monitor, freedivers can access their underwater performance stats without having to look at their wrists. The computer includes a bone transducer encased in a soft silicone mask. Using bone conduction instead of earphones, the transducer generates a human voice and communicates the audio via sound vibrations that travel through the skull and inner ear, which the eardrums perceive as audible sounds.

Vincenzo came up with the high-tech idea. We are lucky to have an experienced optic quantum physicist on our team! He started experimenting with simple pulse oximeters found in pharmacies. Then, he had this breakthrough idea to avoid interrupting freedivers’ concentration.

Divers, without the need to read a computer on their wrists, can maintain the best dive position at all times. Freedivers can keep their bodies streamlined without losing focus on their sensations.

Can beginners and competitive freedivers use the Oxama computer differently?

All freedivers (beginners or athletes) can set Oxama to different modes. They can choose the parameters and the exact moment when to listen to the recorded values. The Oxama computer currently has four audio modes: quiet, alert, chatty, and mute.

As a virtual coach, Oxama can help beginners better understand their own physical limits. This is when the blood oxygen saturation information is most helpful. The Oxama computer gives the beginner the information they need to start freediving safely in a controlled manner.

In the case of competitive divers, some of the most valuable parameters are the ascending and descending speed and the head angle. With these parameters, divers can improve their performance by pinpointing their own improvement benchmarks.

Could you give us more details about how Oxama measures blood oxygen saturation and heart rate?

With Oxama situated on the freediver’s face, the computer has close access to facial blood vessels. Our patented technology exploits the optical properties of blood flow to determine blood oxygen saturation and heart rate. The facial artery’s lateral nasal branch—on the side of the nose—is an excellent point of measure. Like a pulse oximeter measures oxygen saturation and heart rate from the blood vessels of the fingertips, Oxama can do the same on the face.

However, there is another benefit to taking measurements on this part of the body. As freedivers descend deeper, their blood moves from their peripheral limbs towards the inner body, and vasoconstriction occurring at deep depth makes precise measurements at the finger or wrist extremely difficult. Hence, the face is an excellent location to measure the blood metrics no matter the depth.

Since divers can access all of Oxama’s data on their smartphones, what are your tips for interpreting the data to extend dive time? Have you found any interesting observations so far?

With data graphs, freedivers can understand how and where to improve their dive time. The blood oxygen saturation and heart rate data are significant indicators—they show divers where they need to improve both concentration and relaxation to reduce their physical strain. Physical effort saps the limited supply of oxygen divers took at the surface. Oxama also uses it to recommend a recovery time between dives. This is a fantastic way to track their general fitness development over time, as well.

During the first phase of testing, our team noticed that their oxygen saturation remained constant for the entire descent period and decreased during ascent in the final meters. In the same way, their heart rates remained constant throughout the descent and then began to increase during the ascent.

Another interesting observation was the impact of the head angle in ascent and descent—the more aligned with the rest of the body, the better. By not requiring divers to look at a computer on their wrists, Oxama helps them maintain optimal alignment. The same applies to descent and ascent speed which need to be as consistent as possible to maintain energy efficiency.

When will free divers be able to try Oxama computers in 2022?

Our goal is to launch the Oxama freediving computer in July 2022, when, hopefully, freedivers will be able to buy it from our website. We are also currently negotiating retailing deals with dive shops in Italy before expanding globally.

To that aim, we have started organising test sessions in diving pools. In mid-February, we will do a session at the Y-40 deep pool in Padova, Italy, with its technical director, Marco Madollo. We want to repeat the test in March 2022 with free diving athletes.

DIVE DEEPER

Website: Oxama

InDepth: The Making of the Biometric Diver: DAN Europe’s Alessandro Marroni is Realising a 50-year old Dream

To explore additional stories, videos and webinars on freediving click: FREE

Florine Quirion is a writer, underwater photographer, and dive travel blogger at World Adventure Divers. She dives in tropical to extreme cold waters and selects destinations where adventurous diving and cultural discoveries are a part of the journey.