Cave

Madagascar Madness

Earlier this summer Jake Bulman and the Protec Team launched their 2023 expedition to Madagascar’s formidable Malazamanga cave known for massive tunnels, formations the size of buildings, and its unbelievable cobalt blue water. They then journeyed to Anjanamba, which despite enormous passageways, consistently turned into tight, restrictive spaces before opening up again. Having appeased the cave spirits and returned safely, Bulman offered up this account.

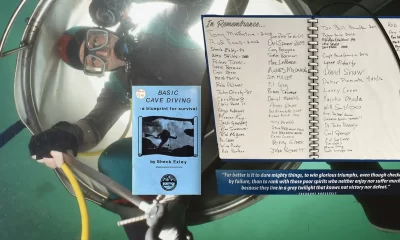

by Jake Bulman. Photos by Phillip Lehman. Lead image: (L2R) Jake Bulman, Patrick Widmann and Ryan Dart motoring through the first mega-room after Ryan’s Chamber, Malazamanga.

Deals made. Plans Laid

As I sat in the Paris airport working on my computer, Patrick Widman gestured to me to remove my headphones. He and Phillip Lehmann sat across from me and asked if I wanted to make a deal. Assuming I was walking into some kind of joke, I replied with a hesitant “Sure.” “Next summer you come with us to Madagascar, if you…“ “Yes! Deal, ” I answered before he finished explaining my end of the deal. It didn’t matter, the answer was yes. Patrick finished laying out his already agreed deal, headphones went back in and everybody went back to what they were doing, except for my thoughts, which went to “Holy Shit! I’m going exploring in Madagascar!”

Now nearly a year later in June 2023, we were back in Paris, this time packing all of the bags for the flight to Antananarivo (“Tana”), Madagascar’s capital city. When we got there we met up with Tsoa, who is the local contact, translator, organizer, and overall critical part of the team. Our bags headed to Toliara with the drivers while we spent the day doing some errands.

The next day was important to me, not because i turned 30, but it marked the end of a bet Patrick and I made in 2020, for which I had now won $100. The victory was short lived, however, as I spent that day stuck in my hotel room violently sick. Welcome to Madagascar!

After a short flight, overnight in Toliara, then an hour long boat ride along the coast, we reached Anakao Ocean Lodge. This place is a bit of a shock to the senses after traveling through the poverty stricken cities. Luxury in the middle of nowhere; it would be our basecamp for the trip. As Patrick and I posted a photo of the place, Phillip sarcastically mourned the loss of any “hardcore expedition” image people would imagine.

The next day we planned to meet up with the National Parks’ representatives, organize porters, transport all the equipment to the site, then get in the water and place all of the deco tanks and scooters we would need, and finally be out by dark to avoid being stranded overnight. This may seem overly ambitious, and it was, but is a good example of the overall approach of the project. Always go all in, no shortcuts or laziness, and if it was not possible in the end, no worries at all. The goal is to have fun with the group and do awesome stuff, which we always did.

”This is the most epic cave ever”

Phillip Lehmann on Malazamanga

Musing on Malazamanga

Malazamanga, a cave of indescribably massive tunnels, formations the size of buildings, and amazing blue water dominated the first part of the trip. We set up a little basecamp in the mouth of the cave, each of us with our own spaces to change, hang up our suits to dry, and change sorb each day. The entrance swim is a tediously frustrating one for rebreather divers: 20 minutes of low ceilings, bouncing from 20 m to 5 m/66 ft to 16 ft and back several times, never allowing space to sit “in trim”, and no flow to remove any of the inevitable silt that came from passing with multiple scooters, stages and divers.

However, once you reach Ryan’s Chamber, the first big room, you find a staging spot for leaving scooters and tanks for the following day, and a small tunnel leading to the real, intimidatingly massive, Malazamanga.

Patrick and I went to the deep section right away (45-50 m/138 to 164 ft) and spent three days trying to find the way on, while Phillip and Ryan Dart looked around the shallower parts of the cave (20-30 m/66-100 ft) for any leads that had not been checked. Patrick laid line while I surveyed behind him through a wide but low space that became swirling silt and clay by the third tie off. We reached a vertical shaft, Patrick asked me to hold and ran a line into a smaller tunnel below us that led to a restriction. In spaces like this where zero visibility is guaranteed, diver two will be pushing through restrictions blind, having no idea the shape or size of the space around them, which is a recipe for disaster, so I waited on the line for Patrick to return and started a timer.

As fifteen minutes showed on the timer, it started to feel like a long time. How long do I wait before doing something? Five more minutes rolled by, and my mind started to run… What if he has a problem? Does he need help? Memories of having to get somebody out of a similar space once before came to mind. But this time it was Patrick though, if he truly needed help it would be a serious situation. I decided to give him until 30 minutes from when he left, and then I would go in (slowly). With four minutes remaining, a glow appeared before Patrick explained that “it’s tight, but it goes.” It was a long wait that meant a bunch more deco, but this could be the way on.

The next day I was tasked with pushing the End Of Line (EOL) while he and Phillip looked elsewhere. After twisting, turning, removing tanks, and wondering if this was a good idea more than a few times, I pushed through a few ups and downs, but the cave unfortunately ended in a basement section at 52 m/170 ft. No going leads. Time to head home.

Breakthrough and Packing Techniques

Our daily routine started at 06:30 with a breakfast of bread, fruit, eggs, tea and espresso. We’d leave the garage at 07:00, meet the porters at the bottom of the hill in the national park and send the equipment with them. Phil would then educate us on the risks of breakthrough, importance of proper packing techniques, and the impact of dwell time. All of which are critical to making espresso.

After making espresso, the handpresso is put away, we hike the 30 minutes up the hill, get dressed, dive four to six hours, then head home. Back at the garage by 08:00 pm, fill tanks for an hour, eat dinner at 09:00 pm, and then sleep. All the while making jokes, sharing stories, talking about life, trying to blind each other with lights, and being shown the same photo of Rosie, Phillip’s pit bull, with a “look at this awesome photo” preceding the photo display by a few seconds.

All in all, going diving required some effort, not to mention the week of traveling with piles of luggage to get there, the week to get home, and all of the time spent organizing beforehand. In terms of “cost (time/money/effort) per hour underwater” it is some of the most expensive time I’ve ever spent underwater.

One day, after a significant amount of problem solving in the hot, muddy entrance tunnel of the cave, we finally got everything sorted and started doing checks. Halfway through, Phillip said, “I’m not into this. You guys go. Nobody is paying me to do this,” and started to remove his tanks. Considering the “cost per hour underwater,” I think many of us would go whether we wanted to or not, giving in to a sunk cost fallacy-like sense of commitment.

We reformed a plan for the two of us, a few angry birds levels were completed on the surface, and everybody went home excited to see the survey data. There is a lesson to be had here for many of us, about what is actually important and ignoring those perceived, often self-induced pressures to carry on even if it doesn’t actually make sense.

We scoured every corner of the section we were in, until a hole underneath a formation showed a large room on the other side. I tied in at ~40 m/~130 ft, headed down the slope to where floor met wall, removed my tank, locked the reel, threw it through the hole, and headed in. Once my torso passed the squeeze, still inverted in the water, I put my tank back on, grabbed the reel, and swam the direction that I remembered it went. I passed the cloud and made a tie off. Turn, tie off, into a bedding plane, tie off, big room, tie off, and stop.

The floor suddenly featured huge, wavy marks that everybody recognizes as signs of flow. A lot of it. Massive clay bricks fit together like tiles in the riverbed resembling floor. A promising development, I tied off and ducked my head under the lip of the ceiling. Instantly the ceiling met the clay bed and the cave ended. Water unfortunately doesn’t consider human size in its choice of direction. Back to the drawing board.

“Fuck it, let’s just see what happens”

Patrick Widmann

To Breathe or Not To Breathe

At the time, the furthest reaches of Malazamanga was an enormous collapse with no way beyond it except a few air domes. We were aware the air domes may not be breathable, but lacked a proper analyzer for that. After some thought, Patrick decided that we would just give it a go one at a time. We surfaced and knelt close together as Patrick closed his DSV and took a short breath of the gas. Wearing an expression resembling somebody tasting less-than-appetizing looking food he took a second breath.

Watching intently, I saw the expression quickly change from hesitant but ok, to uncomfortable to concerned as he put his DSV back in and opened it. I was ready for him to pass out as we sat there breathing, but nothing happened. We knew it was likely not breathable, but I wanted to see what it felt like! I removed my DSV and took a breath. A humid, thick, shockingly hot breath filled my lungs and I was not going to take a second one. No way that was safe, I thought, as the burning in my lungs slowly faded.

Patrick climbed out with just his rebreather (and flowing oxygen) and took a quick look around, but no luck. As he was getting dressed again, I popped my head into a few holes and found a passage that looked to slope downwards on the other side of a tight squeeze. I ran a line in with Patrick behind me, and tried to push through but couldn’t fit. After removing myself and the cloud of unavoidable silt surrounded us, I grabbed the rock that was in the way and flipped it over. If you have ever moved a big rock in a collapse, in a never-before-dived cave, you can imagine the visibility afterwards. We backed out, went to check a few other places, then returned hoping for slightly better visibility.

Patrick was the next one in, leaving a tank on the line with me this time, and he extended the line down the slope on the other side. I heard rocks falling, tanks banging on rock, grunting, laughing, bubbles moving along the ceiling, and then he returned with his hands shaking like crazy. Whatever was over there, was not for the faint of heart it seemed. After a bit of cooling down, he went back into the cloud, which was followed by loud yelling. Excited yelling. We exited, and planned our return for the next day. What lay beyond the 6 m/20 ft deep, vertical, awkward, tank-off restriction was an open space that continued downwards to what appeared to be 40 m+.

The next day, I was going through first. We rehearsed the shape of the restriction and the series of movements needed for passing it on the surface. It was weaving through the space where collapsed boulders met the sloping ceiling, and any extra force on the wiggling rocks meant possible collapse. The plan was for me to pass, tie into the EOL, and head off. Patrick would pass behind me with the MNemo and survey in. Adding tie off after tie off, I headed deeper, then flattened out, then up through an opening to my right. Now it was my turn to yell, the cave had returned to its previous enormous size!! This celebration lasted three tie offs, as we climbed yet another collapse that was quite clearly the end. Cut line, put reel away, look around knowing that nobody will ever be here again, and head home.

On to Anjanamba

Several options lay ahead of us, which Patrick and Phil weighed over dinner. Continue searching in Malazamanga, or get the filming done then head north to Anjanamba, or spend the next two weeks surfing. The last option was apparently way more valid than the joking suggestion I had taken it as. Fortunately, the second option was the choice. We spent a day scootering around with lights in hand and on the DPVs. Screen grabs of the video were used as photos for this article.

We also had two surfing days, where I (having never surfed before) mostly tried to not get annihilated by the waves. My second goal was “not to kill anybody” as Patrick and Phillip repetitively warned me not to do it with my oversized board (only a stand up paddle board was available). Fortunately I’m a very strong swimmer, as I spent large chunks of time crashing and burning, then being tossed around by the ocean.

”This is the most epic cave ever”

Phillip Lehmann on Anjanamba

Heading up to Anjanamba featured a boat ride, a seven hour drive that resembled one of those truck commercials trying to show how tough its product is, and a journey through the Mikea National Park which had no paved road either. During lunch break everybody commented how much better it is now than it was several years ago, describing it as “pretty smooth” and “less violent” in the same sentence.

We visited the local village, where residents are the spiritual keepers of Anjanamba, to talk to the chief and say hi to a friend of Tsoa who had just had a baby. While there we got a tour of their newly built school, joked with the children a bit, took a photo and headed home. For a lifestyle that is so drastically different to our own, with so much less of everything tangible, the village seems a happy, lively place with kids running and playing. However it is easy to see the need for food, schooling, health products, and basic medical care to name a few.

Appeasing the Spirits of Anjanamba

Anjanamba is the location of the filming of the “Spirits of the Cave ” series (see DIVE DEEPER below). Described as a much more dendritic, Mexican-like cave with a blue color that puts the famous Mexican salt water tunnels to shame. The name of the series doesn’t come from nowhere; this cave is home to several spirits. In order to appease them, a few things need to be accomplished.

First, we must visit a big, double trunked baobab during the walk there. We remove our hats, gather near the meeting point of the trunks, place a pointer finger on one tree and pinky on the other (think bull horns hand shape), bow our heads and ask the spirits for two things. One, that they allow us to find an epic cave that goes. Two, that they grant us safe passage and everybody returns home safely. The ever-present, always watching lizard that lives there looked down in approval. The locals however, who had no idea what we were doing, waved us back to the path with a smile and laugh.

Once that is done, a ritual must happen with the Mikea people (in which the National Park is named after). Patrick and Phil have already been through it, so it’s just me. The chief started the ritual, as they each took a sip from a bottle of rum we had brought. Tsoa explained to me afterwards what they had been saying (asking the spirits to accept me, safe passage etc). Notably, it included nothing about finding mega cave, but we had already covered that during the lizard tree ceremony I guess.

The guys had warned me about the second part of the ritual, which had me eating a part of the cave – sand, dirt, rock, whatever. The chief continued speaking, and Tsoa told me it was time. I pinched some sand, put it in my mouth and swallowed. Phillip verified it was all gone. In the background I hear Patrick stifle a laugh, and my long-held suspicion was proven true, this was not actually part of it. The locals found it hilarious, and it wasn’t as if I was going to say no in any case. Diving time.

As usual, we were quite late and had made very ambitious plans which didn’t quite pan out. But we did as much as we could, then headed back to our new home at “Laguna Blu.” Like in Anakao, we had great food, friendly staff, beautiful views and comfortable sleeping.

Reel Bashing

Having laid less line than we had hoped in Malazamanga, we were keen to “bash some reels”. Anjanambas current EOL lay at more than 2287 meters/7500 feet with an average depth of 18m/60 ft or so. It featured enormous tunnels and decorated rooms, yet consistently turned into tight, never-quite-ending spaces before returning to vast rooms with pristine formations all over the place.

Patrick and I each carried a stage, and I carried the back up scooter. Passing through the 30 minutes of sideways swimming, weaving up and down, belly scraping, up and down cave with a negatively buoyant scooter in between my legs meant it was not always smooth sailing. Fortunately it usually got stuck when I was in the back so nobody saw. We reached the end of the line, Phillip tied in and headed off with Patrick recording and me surveying behind them.

From my POV, it looked likely to end every 10 tie offs only for the line to weave into a little corner of the room and continue, with nothing but a light dusting of silt at each tie off as signs of my team ahead of me. This repeated for another 457 meters/1500 ft of line until the reel was emptied, everybody cheered and fist bumped with excitement and then decided that we really needed to head home.

Our DPV charging plan didn’t pan out, so after each day Patrick and Phil drove over to a neighboring location and ate lunch while the scooters charged. I went back to Anjanamba and swam some of the closer lines checking for any going cave. After extending a few EOL’s, the sections had been checked without much luck. After a few days of exploring in Anjanamba, which mostly featured a repeating pattern of restrictions then big rooms, we finished our last diving day with nothing clearly going, but a few hopeful areas left.

End of the Line

As we reached the end of the trip, instead of feeling tired as we expected, we found ourselves ready for more. We had lots of sorb left, but had used every last liter of oxygen. Unfortunately, it was time to take a group photo with the locals, dry our equipment and start the journey home. Not only did we have flights to catch, but we had classes to teach less than 12 hours after landing in Mexico.

After five weeks of expedition, we had managed to get the most out of every day, be on time almost never, and explore some amazing cave. More impressively, I don’t recall a single argument or bad mood at all, which is rare when you spend 18 hours per day with the same people. Until next time, the villagers return to their normal lives, we go back to the Caribbean, and the spirits of Anjanamba can rest again.

We did have one last day before heading home, in which we would make a discovery. What will come of it is yet to be seen, but I’m sure it’s going to be a mega-epic either way. In fact, probably the most epic cave ever.

DIVE DEEPER

The Protec Team‘s past Madagascar Expeditions:

YouTube: Spirits of the Cave (2017)

YouTube: Spirits of the Cave 2 (2019)

YouTube: Spirits of the Cave 3 (2020)

Originally from Canada, Jake Bulman is a full-time cave diving and CCR instructor at Protec Dive Centers in Mexico. The last several years of teaching have been almost exclusively sidewinder focused, from try dives to CCR Cave classes, 4C to 24C, and in several countries around the world. Outside of work, he can be found on exploration projects in local caves of a wide range of depths, distances, and sizes.