Education

Maintaining Your Respiratory Reserve

Just like skeletal muscles, respiratory muscles have a limited ability to respond to respiratory loads, and when they can’t keep up underwater due to increased gas density at depth and the added load of your rebreather, you may be in for an “eventful” dive. Retired scientific director of the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU), Dr. John Clarke has the deets.

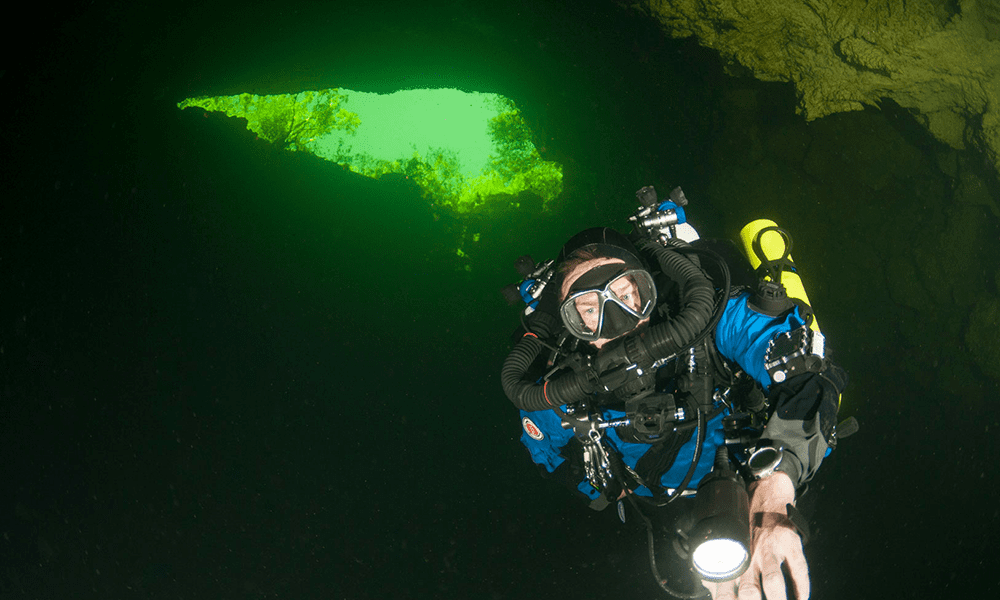

by John Clarke. Images courtesy of John Clarke unless noted. Lead image: Jarrod Jablonski aka JJ, on his JJ-CCR. Photo by Andreas Hagberg.

Just like skeletal muscles, respiratory muscles have a limited ability to respond to respiratory loads. An excellent example of this is a person’s inability to breathe through an overly long snorkel (Figure 1.) Our respiratory muscles simply aren’t strong enough to overcome the pressure difference between water depth and the surface.

The primary respiratory muscle is the diaphragm, (the brown organ lying below the lungs in Figure 2.) The diaphragm is designed for low-intensity work maintained 24/7 for the entirety of your life. Like the heart muscle, its speciality is endurance. When called upon to maximally perform, the diaphragm needs assistance. That assistance is provided by the accessory respiratory muscles, primarily the intercostal muscles linking the ribs within the rib cage.

The human diaphragm separating the lungs from the abdominal cavity. Graphic by John Clarke.

Unless you’re reading this while running on a treadmill, your body is probably idling. Your heart is beating rhythmically, your diaphragm is methodically contracting and relaxing. But, if some dire event were to happen, you would be primed for action. If you needed to react to an emergency, your heart and lungs would race at full speed.

The difference between idling and full-speed capability is called physiological reserve, which in turn is divided into its components; cardiac, muscular, and ventilatory reserve. As drivers, pilots, and boat captains will attest, it’s always good to have fuel reserves. Likewise, physiological reserve is good to have in abundance.

The Dive

The following is an imaginary tale of a young, blond-haired hipster drawn to the Red Sea for a deep dive. He chose to dive on the wall at Ras Mohammed on the Eastern Shore of the Sinai, which descends quickly down to a thousand feet and beyond. That was his target—1,000 feet.

The previous year he bought a rebreather so gas usage should not be a problem for his deep dive. He also sprang for the cost of helium-oxygen diluent. Trimix would have been cheaper, but he spared no expense. Nothing but the best. To that end, he used loose-fill, fine grain Sodalime in his scrubber canister.

These were his thoughts as he descended.

Free-falling at three hundred feet. Never been this deep before. The water’s getting cold, so the warm gas from the canister feels good.

800 feet. Wow, the gas is thicker now.

When he reached the bottom, he realized something wasn’t right. He sucked harder and harder, feeling his full face mask collapsing around his face with each inhalation. He was “sucking rubber,” feeling like he was running out of gas, but his diluent pressure gage still read 1800 psi.

Unconsciously, he compensated for the respiratory load by slowing his breathing—easing his discomfort. Concerned, he briefly switched to open circuit bailout gas, but that didn’t feel any better. In fact, it was worse, so he switched back to the bag.

Surprisingly, he couldn’t get off the bottom. In fact, he was slipping further downslope. He needed to drop weights, but they were integrated. He fumbled with his vest, trying to remember how to release the weights, but he couldn’t work it out.

He found the pony bottle to inflate his integrated BC, but after a second’s spit of air, it stopped filling. He would have to swim off the bottom. As he struggled to swim upwards in the darkness, and without bubbles to guide him, he wasn’t sure which way was up.

His heart was beating at its maximum rate, trying to force blood through his lungs, but he couldn’t force enough gas in and out of his lungs to clear his bloodstream of its increasingly toxic CO2 load. The build-up of CO2 in the arterial blood was clouding his thinking. The CO2 was making him want to breathe harder, but he couldn’t. The feeling of breathlessness—and impending doom—was overwhelming.

—

The accident investigation on the equipment was inconclusive. The dive computer had flooded, but that was irrelevant. Surface pre-dive checks were passed. The rebreather seemed to function normally when tested in a swimming pool. The investigators convinced a Navy laboratory to press the rebreather down to 1,000 feet, but nothing abnormal was found other than a slight elevation of controlled PO2.

The Analysis

An asthma attack can kill by narrowing the airways in the lung, making the person suffering the attack feel like they’re sucking air through a clogged straw.

A healthy diver doesn’t have airways that constrict, but gas density increases with depth, causing the same effect as a narrowed airway. It becomes increasingly difficult to breathe as depth increases. A previous InDEPTH blog post on gas density discusses this subject.

If the strength of respiratory muscles is finite, just as it is for all muscles, then any load placed on those muscles will eat away a diver’s “respiratory reserve.” From the diaphragm’s perspective, the total loading it encounters is divided between that internal to the diver and that external to the diver. As gas density increases, internal loading increases. A rebreather is external to the body, so flow resistance through a rebreather adds to the total load placed on the respiratory muscles. If the internal resistance load increases a lot, as it does at great depth, there is very little reserve left for external resistance, like that of a rebreather.

In this fictional tale of a hapless diver, he needlessly added respiratory resistance by using fine-grain Sodalime in his scrubber canister. Compared to large grain Sodalime, such as Sofnolime 408, fine-grain absorbent adds scrubber duration, but it also increases breathing resistance. It thus cut into the diver’s ventilatory reserve.

This fictional diver exceeded his physiological reserves by

1) not understanding the effect of dense gas on the “work of breathing,”

2) not understanding the limitation of his respiratory muscles, and

3) by not realizing the “best” Sodalime was not the best for breathing resistance.

He also didn’t realize that a rebreather scrubber might remove all CO2 from the expired gas passing through it, but it is ventilation (breathing) that eliminates the body’s CO2 from the diver’s bloodstream. Once CO2 intoxication begins, cognitive and muscular ability quickly decline to the point where self-rescue may be impossible.

Lessons From The U.S. Navy

Considering the seriousness of the topic, it is worthwhile to review the following figures prepared for the U.S. Navy.

First, we define peak-to-peak mouth pressure, a measure of the pressure exerted by a working diver breathing through the external resistance of a rebreather. Total respiratory resistance for a diver comes in two parts: internal and external. In the following figures, those resistances in the upper airways are symbolized by a small opening, and in the external breathing apparatus, by a long, narrow opening representing a UBA attached to the diver’s mouth.

This author reviewed over 250 dives by Navy divers at the Naval Medical Research Institute and the Navy Experimental Diving Unit. These were working dives involving strenuous exercise at simulated depths down to 1500 feet seawater, using gas mixtures ranging from air to nitrox and heliox. Gas densities ranged from about 1 gram per liter (g/L) (air at the surface) to over 8 g/L. Each dive was composed of a team of divers, so each plotted data point had more than one man-dive result included. An “eventful” dive was one where a diver stopped work due to loss of consciousness, or respiratory distress (“dyspnea” in medical terminology.) They were marked as red in the following figure. Uneventful dives were marked in black.

Using a statistical technique called maximum likelihood, the data revealed a sloping line marking a boundary between eventful and uneventful dives.

The fact that the zero-incidence line sloped downward illustrates the fact that the higher the gas density, the greater the respiratory load imposed on a diver by both internal and external (UBA) resistance. The higher that load, the lower the diver’s tolerance to high respiratory pressures.

By measuring peak-to-peak mouth pressures, we are witnessing the effect of UBA flow resistance at high workloads. It does not reveal the flow resistance internal to the body. However, when gas density increases, internal resistance must also increase.

The interrupted lines in the figure illustrate lines of estimated equal probability of an event. The higher the peak-to-peak pressure for a given gas density, the higher the probability of an eventful dive.

Figure 7 suggests that at a gas density of over 8 grams per liter, practical work would be impossible. The only way to make it possible would be to reduce gas density by substituting helium for nitrogen, or substituting hydrogen for helium, and then doing as little work as possible to keep ΔP low.

For our fictional 1,000 foot diver, the gas density would have been between 6 and 7 grams per L. Using a rebreather, there would be virtually no physiological reserve at the bottom. Moderate work against the high breathing resistance at depth would be very likely to result in an “eventful” dive.

Image Citation for medical graphics: Robieux, Camille F, Christine Galant, Aude Lagier, Thierry Legou and Antoine Giovanni. “Direct measurement of pressures involved in vocal exercises using

semi-occluded vocal tracts.” Logopedics, phoniatrics, vocology 40 3 (2015):

106-12 .

DIVE DEEPER

Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine: Fatal respiratory failure during a “technical” rebreather dive at extreme pressure

Diver Records Doom | Last Moments-Dave Shaw

John Clarke, also known as John R. Clarke, Ph.D., is a Navy diving researcher in physiology and physical science. Clarke was an early graduate of the Navy’s Scientist in the Sea Program. During his forty-year Navy career, he conducted physiological research on numerous experimental saturation dives. Two dives were to a pressure equivalent to 1500 fsw. For twenty-eight years he was the Scientific Director of the Navy Experimental Diving Unit in Panama City, FL.

Clarke has authored a technothriller-science fiction series called the Jason Parker Trilogy. All three volumes, Middle Waters, Triangle, and Atmosphere, feature saturation diving from depths of 100 feet to 2,500 feet. The deepest dives involve hydreliox, a mixture of helium, hydrogen and oxygen. UFOs, aliens, and an uncaring cosmos lay the framework for political and human intrigue both on and off-planet.

Although recently retired, Clarke still works for NEDU as a Scientist Emeritus and contractor, when he isn’t writing about diving, aviation, and space. His websites are www.johnclarkeonline.com and www.jasonparkertrilogy.com. His thriller series is available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.