Education

Measuring Your Workload While Diving

How do divers’ workloads vary, for example, when diving doubles vs. singles, adding stages, or motoring to the dive site on their favorite DPV vs. frog-kicking? Avid cave diver cum university researcher Peter Buzzacott offers a practical tool to assess your underwater wattage.

by Peter Buzzacott

Most technical divers understand and know how to calculate their Surface Air Consumption (SAC) rate, which is typically used in gas planning. But did you know that SAC rates can also be used to measure various workloads—for example, the difference in workload when diving doubles vs. singles, using various techniques, or under different environmental conditions?

Let’s use an example to recap the theory; I’ll use metric throughout this blog for simplicity. A diver is at 10m depth, which is 2 ATA in the sea. The diver’s tank is a standard 12-liter tank filled with 200 bars (plus a safety margin); therefore the diver has 2,400 usable liters of gas at the surface. At 10m depth, that would be down to 1,200 breathable liters, and if the diver used the whole 1,200 L of usable gas over one hour, then the diver’s surface equivalent breathing rate would be 1,200/60, which is 20 liters per minute—a common, if slightly high, breathing rate. One might argue the actual breathing rate is 40 liters per minute, and that the equivalent of 40 liters per minute comes out of the tank, but it is actually compressed down to 20 liters because the diver is at 2 ATA. This is why we call it surface air consumption— because even though the breathing gas is twice as dense at 10 meters depth, the breathing rate is equivalent to 20 L/min at the surface (not 40 L/min at the surface). Of course, the air is twice as dense, so the work of breathing is greater, but SAC does not account for this.

Okay, that’s the math out of the way. In the real world, divers often use the average depth from their dive computers to estimate the average ambient pressure throughout the dive, then divide the volume of gas used by the number of minutes spent underwater and the average pressure. This gives a fairly accurate estimate of the surface equivalent breathing rate. For part of my PhD research, I clipped accurate depth loggers to the chest D-rings of divers and recorded over 1,000 recreational dives. I also used a calibrated pressure gauge to measure the tank pressure before and after each dive, and noted the tank volume stamped on each tank. Then, I asked every diver if they thought the workload during their dive was “resting/light,” “moderate,” or “severe/exhausting.”

Good in the SAC?

In the 1980s, a scientist named Dwyer had divers fin at a certain pace against a set resistance and measured both their SAC and how much oxygen remained in their exhaled gas. This was done at a few set depths, including a series of dives at 10m depth. An equation was generated for each depth to convert SAC into oxygen consumption. The mean depth of my 1,000 recorded dives was 10.7 m, so I used Dwyer’s 10m equation to convert everyone’s SAC into oxygen consumption. I then made one last conversion by dividing everyone’s oxygen consumption by their weight (in kilograms, of course). This standardized the oxygen consumption across the whole range of divers, from small to large and whether male or female.

Interested readers can read my paper, but to make the results meaningful here, I’ll compare the dives by how many metabolic equivalents (METS, i.e., the rate at which a person expends energy relative to the mass or weight of that person) each dive represented. When our oxygen consumption is at its lowest, for example, when we are asleep, we consume around 3.5 ml/kg.min of oxygen, which is by convention considered to be 1 MET. If I consume 35 ml/kg.min of oxygen while running on the treadmill, then I would be running at 10 METS.

In my study, the divers who said their dive was relaxing had an average workload of 5.3 METS. It is important to remember that is an average, because some people had a very low SAC and some people really chewed through their gas, but the average for a resting dive was 5.3 METS, which is about the same as a brisk walk. The dives with a moderate workload averaged 5.8 METS, which is about the same as riding a bicycle at a modest pace (~15 km/hr), and the severe/exhausting dives averaged 6.2 METS, which is about the same workload intensity as an aerobics class.

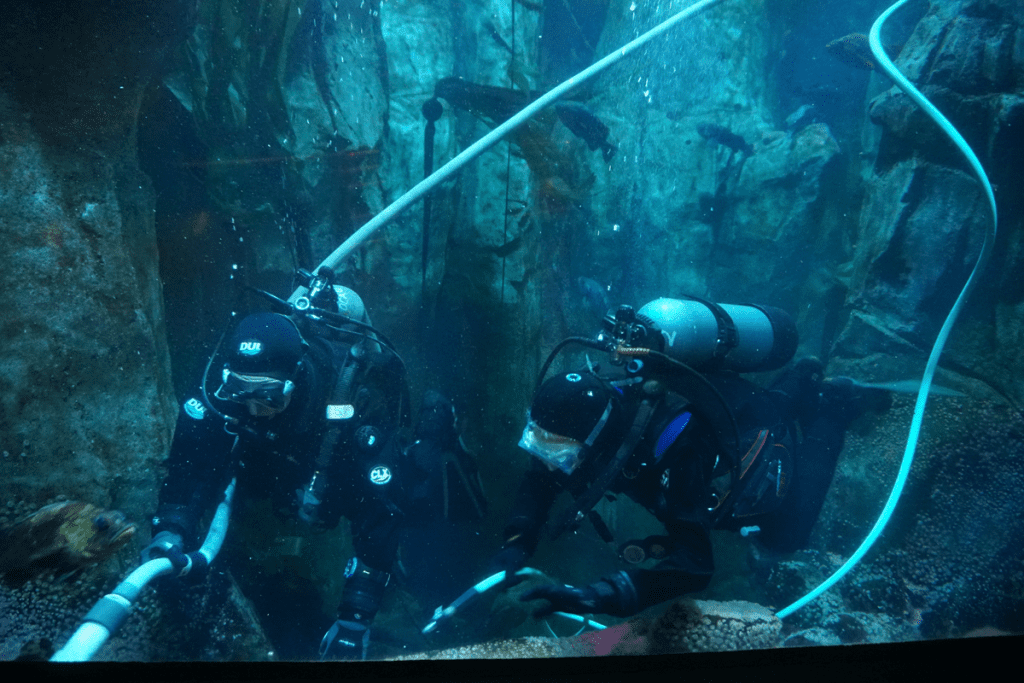

Dwyer also recorded his divers’ heart rates and tried to generate equations to link SAC with heart rate. Recently I tried something similar and took a research team to Oregon to measure SAC and heart rate in volunteer divers at the Oregon Coast Aquarium. We fitted waterproof EKGs to each diver, plus those sensitive depth/time loggers, and estimated their workload just as I’d described above. But, just like Dwyer, we couldn’t generate a reliable conversion from SAC to heart rate, or vice versa. Therefore, the most reliable estimate of workload that we divers have is, in my opinion, SAC/kg. To give some sort of guide, the “resting/light” divers in my PhD research had an average SAC/kg of 0.21 L/kg.min, the moderate divers 0.23 L/kg.min, and the exhausted divers 0.29 L/kg.min.

As we all know, good trim is essential for reducing workload while diving—as is correct weighting and good buoyancy control. Other factors include finning technique and drag. Using SAC/kg, divers can measure for themselves how much of an effect there is when going from a single tank to a set of doubles, or when adding a stage or multiple stages. Divers can also see just how much of an improvement they make when they perfect their technique over many dives—for example, their DPV technique. [ed: It’s OK to try this at home kids!]

Another advantage of SAC/kg is that it can be compared within a dive team between males and females, between small divers and big divers. In Oregon, the aquarium divers were in drysuits, the water was cold, and the divers were working (cleaning the viewing windows, vacuuming the floor, etc). Their average SAC/kg was 0.26 L/kg.min, which was equivalent to a moderate-to-difficult workload. The full paper was published in the latest issue of Occupational Medicine.

Two divers having their SAC measured while cleaning one of the exhibits. Photo by Peter Buzzacott.

References

Buzzacott P, Pollock NW, Rosenberg M. Exercise intensity inferred from air consumption during recreational scuba diving. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 2014;44:74-8.

Dwyer J. Estimation of oxygen uptake from heart rate response to undersea work. Undersea Biomedical Research. 1983;10:77-87.

Buzzacott P, Grier JW, Walker J, Bennett CM, Denoble PJ. Estimated workload intensity during volunteer aquarium dives. Occupational Medicine. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz011

Peter Buzzacott, MPH, PhD, is a former recreational and technical diving instructor, now a university researcher with more than 60 published papers on diving injuries. He is a Guest Professor at the Second Military Medical University in Shanghai, in the hyperbaric research laboratory that, in 2017, discovered the first nutritional supplement shown to prevent decompression sickness. Before that, he conducted decompression experiments during a two-year post-doctoral fellowship at a university in northern France. He is an avid cave diver.