Community

Meet GUE’s NextGen Scholarship Winner

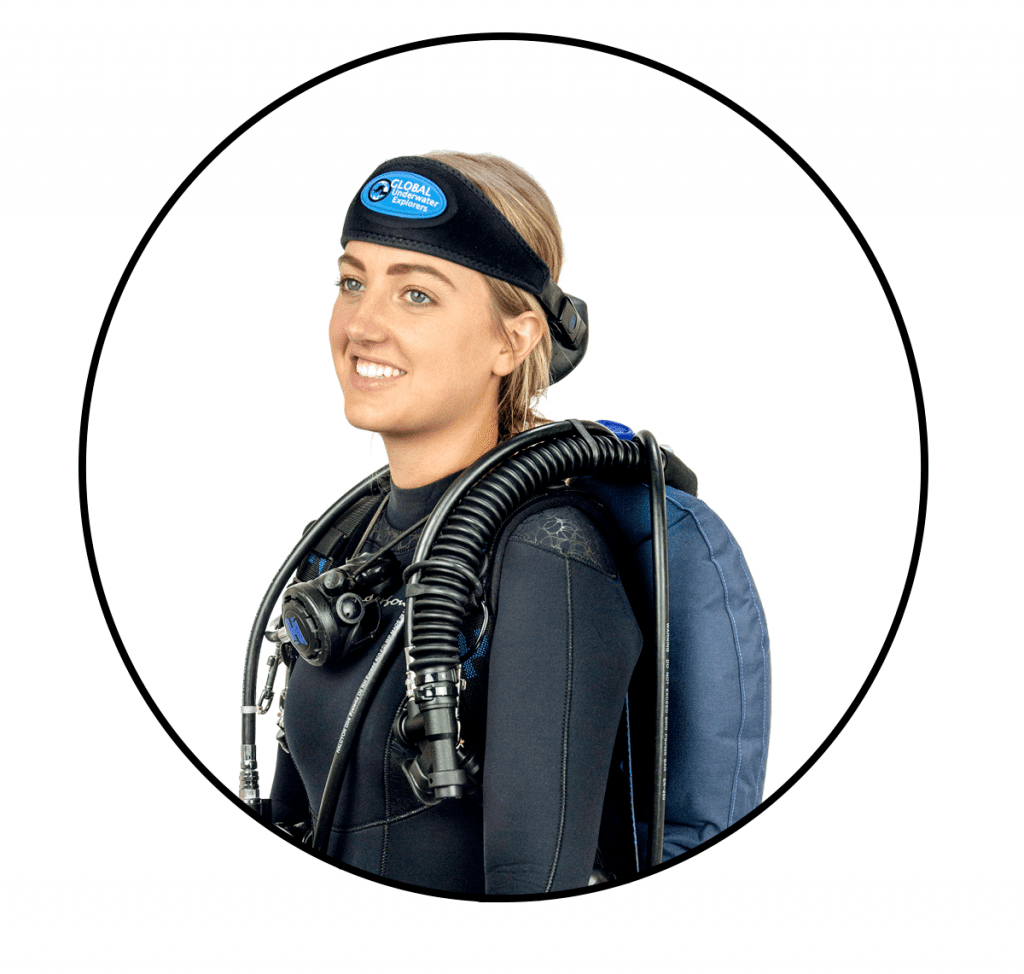

Meet one of the newest members of the family, 25-year old Annika Andresen from New Zealand, GUE’s first ever NextGen scholarship recipient.

by Amanda White

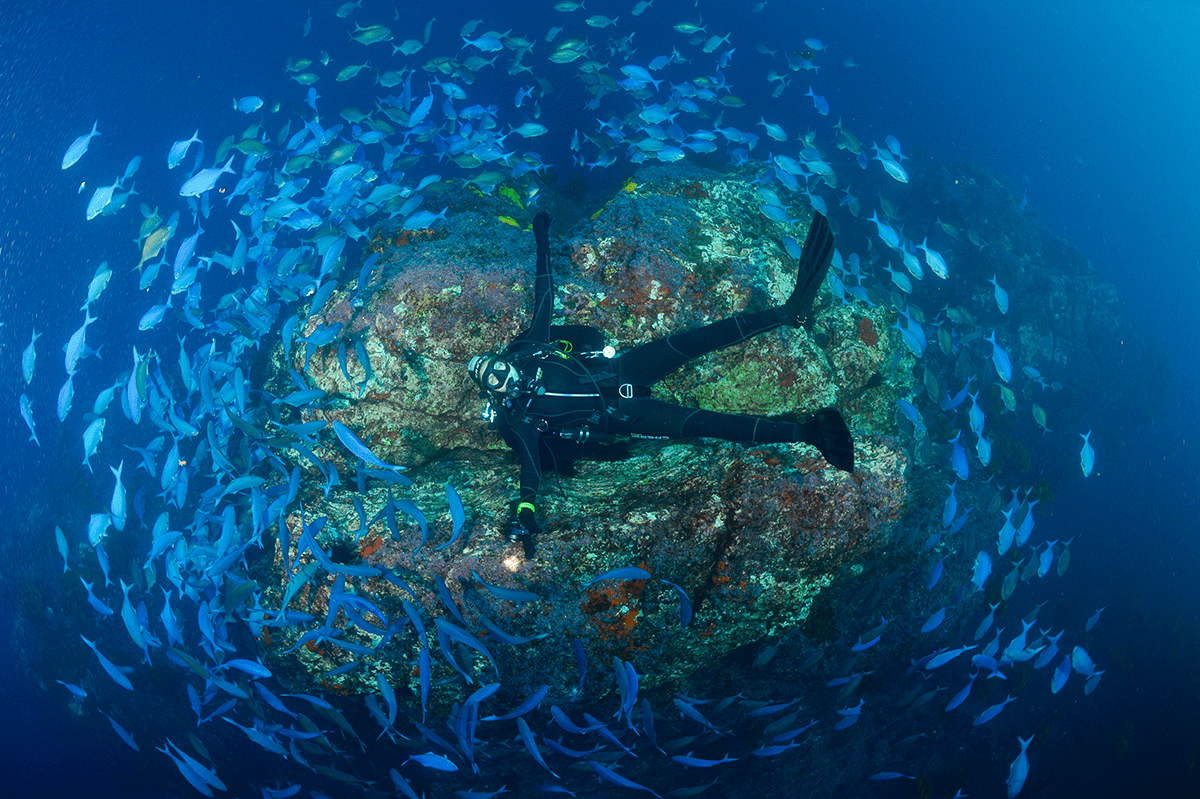

Header photo by Matthew Coutts. Annika diving at the Mokohinau-Islands.

As a way to empower the next generation of divers, Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) created the NextGen Scholarship, which provides a year of training and other benefits to deserving divers on their quest for excellence.

We are excited to announce that the first-ever NextGen scholarship recipient has been selected. Annika Andresen from New Zealand will be our 2019-2020 NextGen scholarship winner! Annika is 25 years old with a Masters of Architecture, where she studied the role architecture plays on the connection people have with their environment. She has also worked on dive boats, is a PADI open water dive instructor, and currently works for Blake, an environmental trust, as an environmental educator.

InDepth caught up with Annika to learn a bit more about her and how this scholarship will help her achieve her goals.

InDepth

We got to know you a little bit through your video and application, but we have a couple more questions to get to know you a little bit better and share your story with our community. What influenced you to pursue diving, and how old were you when you started?

Annika Andresen

I grew up sailing around the east coast of the North Island on a little 9-meter (30-foot) yacht with my family— my parents and two brothers. We were always around or in the water, and my dad let us have a go on his dive gear when we were seven to see what it was like to breathe underwater. We didn’t really go under the water, we were just on the surface, but as we got older we joined him on more of his dives. It wasn’t until my first year of university where I got enough money to do my open water course in 2013, but it feels like I have been diving my whole life.

What attracted you to diving over other water sports?

Just being closer to everything and being fully immersed. If I was snorkelling, there is only so long I could hold my breath, so I really wanted to learn how to dive so I could actually stay submerged and watch the different marine life swimming around and become part of the environment. That’s kind of what started it off. I had a good friend in the Auckland University Underwater Club who was also interested, so we did the course together. After my first year at University I wanted to get a summer job that involved something to do with the ocean. I emailed Kate Malcolm at Dive! Tutukaka, asking if there were any jobs working on the boats as crew. On my trial we saw dolphins almost every day, got to take customers in the water to experience the marine life, and were teaching everyone about the importance of our marine environment. I couldn’t believe this was a real job. I moved up to Tutukaka, where I got to go out to the Poor Knights Islands every day, and on my days off, I was able to gain more diving experience, joining the dive masters with their group. I think it was then when I really fell in love with diving. I was like, “This is what I want to do. This is what I want to fully throw myself into and learn as much as I can.”

How has your connection with the underwater world influenced the rest of your, I guess, so to speak, dry land life?

At the moment, it’s very much influenced… well, I guess the underwater world has always influenced my life. I remember at primary school, every time I was drawing something, it was something to do with the water. My teachers said, “Oh, you’ve got to expand and draw other things,” but that’s all that I wanted to do. In intermediate, we were doing a project about the ocean and I remember sitting down with the teacher and saying, ‘“Instead of just reading about it, why don’t we actually take them out to Goat Island (New Zealand’s oldest marine reserve)?” So somehow, I convinced my teacher and parents to take my whole class to my teacher’s house who had a pool. During one afternoon, we taught them how to snorkel, going through how to put on a mask, and snorkel, and how to be comfortable in the water.

Then the following week, we went up to Goat Island. My dad and I guided my class around the bay, pointing out all the different species while my mom rowed our dinghy (that had a little glass bottom) for the three people that didn’t like being in the water. Everyone was really excited to see the fish. In my architectural degree, all of my designs always included water or a connection to the environment. One of my favorite designs was a marine rehabilitation center sited in the Bay of Islands for different marine species. So I guess everything has always been influenced by the underwater world…for me, it’s my home. I always feel very calm on the water and then diving just ramped everything up a lot more. Now whatever I do seems to be associated with or to revolve around diving or anything to do with water.

Do you participate in any other water sports besides snorkeling and swimming?

Yeah, I love sailing. I do a lot of sailing. Normally every Friday night, I will go down with a group of girls and we do rum racing. So if you win the race, you get a bottle of rum, and then there’s other sailing regattas during the weekend if I’m not diving. If I can’t go diving or sailing, normally the weather is perfect for surfing. My car always has a combination of dive gear, surfboard on top, my wet weather gear, and a towel. I also really like free-diving as well because it’s just very different from scuba-diving, and there are some species I don’t want to scare off with my bubbles.

We saw from your video that you work for Blake. How did you get involved in conservation?

I have always been interested in volunteering for conservation projects and encouraging others to do the same. I was very lucky. In 2016-2017, I was chosen for Blake’s ambassador program where I worked with Antarctica, New Zealand, and the Antarctic Heritage Trust. Through the program, I was able to go to Antarctica and work with the team down there to conserve Sir Edmund Hillary’s Hut.

When I finished my thesis last year, BLAKE approached me over the summer and asked me to help kickstart a new project. This has been the pilot year for NZ-VR, where we have a roadshow traveling to different schools in Auckland. We have 60 VR headsets and spent the year teaching four classes a day, ranging from 10-year-olds to 15-year-olds, about our underwater environment. We put a headset on each student showing 360° footage from New Zealand Geographic that is taken all around New Zealand, comparing and contrasting environments from the very pristine northern parts of New Zealand to degraded environments from human impact that are closer to human populations.

By the end of the year, my colleague and I will have taught 20,000 students in the Auckland region. Hopefully, depending on funding for the project, we want to get two more educators and double the amount of headsets to reach twice as many students and further expand into the surrounding regions. It’s a really awesome organization where they were able to just give me the support that I needed to really push the idea of learning through experience. This is really exciting, as this was what my thesis was based around, and I can combine my passion for the underwater world and creative thinking towards conservation.

Wow. What an inspiring job to have.

Yeah, it’s pretty incredible to be able to get students excited about the ocean, to remove that element of fear if they don’t like the water for some students, and show others that don’t get the opportunity to be able to experience what it is like beneath the surface. It gets students to be immersed and learn empathy toward our environment. The other awesome addition to the videos is the natural underwater sounds New Zealand Geographic recorded, so when the students are experiencing these videos, they can hear everything that you would be able to hear underwater.

What attracted you to GUE?

Very good question. It was actually when I had just started scuba diving, I think I had done 20 dives. At the time, I was seeing someone who had done the GUE Tech One course and he said it would be a really good way of refining my skills and gaining a lot more confidence in the water. I had previously met Mel Jeavons and Jamie Obern on the dive boats and was really interested in the diving they were doing.

I did the Fundamentals course with Jamie on a single tank with a wetsuit just because that’s what I was diving in at the time and what I was comfortable with. Over the next two years, I worked on gaining more diving experience and talking to Jamie, and finally, I was like, okay, I’m ready to go on to twins now. I got my tech pass a year after that. I really valued being able to dive and not disturb any of the environment around me, especially while working at the Poor Knights.

It wasn’t until I started working as a divemaster and guiding people around that it really showed the difference. I was very conscious that I didn’t want to destroy the environment that I was showing people. And being able to share that with people, sharing techniques I had learned or explaining certain elements in diving, I realized this gave confidence to my divers as well. I wanted to ensure every diver had a positive experience, and so they could enjoy their dive and fall in love with the ocean just like I have, giving them a reason to protect it.

What are your diving goals now?

To spend as much time in the water as I can. I would love to dive along the side of a huge iceberg in Antarctica, explore the wrecks of Truk Lagoon, or swim alongside schooling hammerheads in the Galapagos. This list could go on forever…

Furthering my diving skills, I’ve always wanted to try cave diving, and I am truly fascinated by the amazing pictures I have seen from cave divers. There are some caves in New Zealand, which is not an easy place to learn to cave dive, but it has always been one of my life goals to see first-hand what this incredible environment is like.

Over the last year, I have been looking into the GUE Tech One course, and this came after a dive on the MV Rena (a container ship that ran aground on the Astrolabe Reef in 2011). Four and a half years later, the exclusion zone was lifted, and I was lucky enough to dive the wreck a couple of days later. The wreck was split in two and the stern section of the Rena starts in 26 m/85 ft, continuing further down the reef face to 70 m/230 ft. I was stuck at 30 m/100 ft, and I was looking down at this amazing container ship, and I was just like, ‘oh, this is why I want to get my Tech One,’ because looking down on the wreck is just not the same, and the wreck, although so close, seemed so far away.

I have always dreamt of taking every single person beneath the surface and showing them some of the amazing things I have been lucky enough to see. So, one of my main personal goals would be to inspire as many people as I can and take them on my journey to share the importance and beauty of our ocean.

How do you feel the GUE scholarship will help you achieve these? As both a diver and a conservationist?

Just meeting everyone, building on my knowledge, and developing my skills as a diver. Gaining a greater understanding of conservation projects, hearing their diving stories, what they’ve learned, and then being able to share these experiences with everyone. That would be awesome. This scholarship is an amazing platform for me to be an ambassador for the protection of our oceans as well as for women in the marine environment and diving.

It’s a great community, that’s for sure. Had you heard of Jarrod Jablonski before he called you to tell you that you were awarded the scholarship?

I had, because I read everyone’s profiles. I was really nervous when I got the phone call. I started my interview talking to Dorota, and then she got up to get someone. I didn’t know what was going on. Jarrod sat down and it took a little bit to register, and when he said his name I went into a bit of a shock and I was like, ‘What? He’s actually talking to me?’ But yes, it was a bit of a stunned moment; that it was actually him that was talking to me online.

Annika will be joining GUE for their 2019 Conference in Florida from November 9-11th. If you are interested in attending the conference, registration closes on November 4th.

Dive Deeper

Amanda White is the editor for InDepth, and Global Underwater Explorers Content and Brand manager. Her main passion in life is protecting the environment; whether that means working to minimize her own footprint or working on a broader scale to protect wildlife, the oceans, and other bodies of water. She received her GUE Recreational Level 1 certificate in November 2016 and has been lucky enough to join GUE and Project Baseline projects. Amanda holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism with an emphasis on strategic communications and a minor in creative writing from the University of Nevada, Reno.