Cave

Meet The British Underground

It’s cold, dark, you can barely see two meters in front of you, and you’re diving alone. Oh, and there’s a sump up ahead. Welcome to the British Underground! Not exactly a scooter-ride in the warm, clear, stalactite studded caves that lay beneath Riviera Maya. Here British caver and training officer for the Somerset Section of the Cave Diving Group Michael Thomas guides us on a tour of British cave diving and explains why it may not be everyone’s cuppa tea.

by Michael Thomas

Header photo courtesy Michael Thomas. Diver entering Keld Head in the Yorkshire Dales.

Recently someone approached me about British cave diving wondering what in particular makes it so very different from Mexican cave diving, for example, and why it’s so appealing to a select few. In the U.K. we have two types of underground diving. The first is the significant number of flooded mines that have given rise to some world-class mine diving that’s becoming very popular with technical divers from around the world. The second type of underground diving is traditional British cave diving, which, due to the nature of U.K. caves, involves both dry caving and cave diving. The aim is to explore the caves underwater or in the dry underground following it as far as possible. We are now finding that technically trained mine and cave divers are starting to learn the art of dry cave exploration in order to further their knowledge and adventure, some even gaining enough experience to join the Cave Diving Group in the U.K.

Firstly, a little about myself if I may be so bold. My diving career is now in its thirty-third consecutive year, from starting out as a trainee open water diver with BSAC to trainee cave diver within the CDG to becoming the Training Officer of the British Cave Diving Group Somerset Section in the U.K. Since 1996 I’ve had links to TDI and currently hold Full Cave Instructor, Sidemount and Tech Instructor status with TDI, active mod 3 CCR cave diver, and on the British Cave Rescue call out list as a diver.

My diving life crosses all paths of British and worldwide diving, from open water to cave and tech. I’m actively involved with technical diving conferences and a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society of the U.K. My father was a cave explorer before me, and my son has also taken the same path. You could say, caves and diving are our lives.

See The CDG

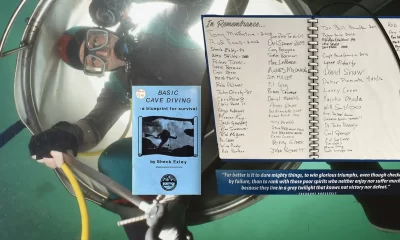

To understand British cave diving we first need to understand the CDG. The Cave Diving Group is the representative body for cave divers in Great Britain and Northern Ireland and is a constituent body of the British Caving Association (BCA). Its function is to educate and support cavers for recreational and exploratory operations in British sumps. The CDG also helps control access to numerous cave sites, including Wookey Hole and Gough’s Cave in Somerset, and Keld Head And Hurtle Pot in Yorkshire, in conjunction with the BCA. The group was formed in 1946 by the late Graham Balcombe, and its continuous existence to the present day makes it the oldest amateur technical and cave diving organization in the world. Graham Balcombe arguably invented cave diving in the U.K. with his audacious dives in Swildon’s Hole cave and Wookey Hole cave in 1935.

Now the huge difference between the Cave Diving Group and other cave diving training agencies is you can’t just sign up and pay to do a training course. From the very start in 1946, the prerequisite for joining the CDG was always and is a knowledge and experience base of dry caving skills, though in modern years we also require an open water certification. Once you have made yourself known to one of the four sections that make up the CDG—Somerset, Welsh, Northern, and Derbyshire—and proven you have dry caving skills and can get along with your new-found friends, you are voted in, hopefully to whichever section you approached.

As a trainee member of the cave diving group, the training is apprenticeship based and generally takes between 12-18 months. At the end of that, a written exam and an underwater test is completed, and as long as your section is in agreement, the qualified diver status is awarded. It’s a slow process but ensures adequate experience is gained in a variety of different sites and conditions, producing a cave diver that is capable of exploration cave diving, rescue work, and continued training of new members.

The Solo Mentality

Probably the one difference with most U.K. cave diving, that is a world away from agency standards, is the CDG approach to team diving. In all but a few sites in the U.K., the CDG considers solo diving the safest way to approach the dive. While divers might enter the cave together as a team, and dry cave their way to the dive base (dive site within the cave), once they are in the water they typically dive solo. This is because a diver is usually unable to help another diver in the water. Then they meet up on the other side if more dry caving is to be done.

CDG trainee divers are taught from the beginning to be solo divers or work within a team as solo divers, something we call “team solo.” Most dive sites in natural caves in the U.K. are unsuitable for team diving. The few sites that are suitable for a team to operate together, such as Wookey Hole in Somerset, Hurtle Pot in the Yorkshire Dales, and Porth Yr Ogof in South Wales, should really be a team of only two divers. Passage size and visibility generally means divers can’t see the third team member if at the back or front of the team. The mine diving sites are much more suited to team diving with larger passages and clearer water. The links below offer more information on mine diving in the U.K. [Ed.note: Global Underwater Explorers does not sanction solo diving.]

The article, “Solo Cave Diving,” on the CDG website explains why it recommends solo cave diving as the safer alternative for U.K. sump conditions. It lists some of the advantages of solo cave diving as follows:

- There’s no one to get physically jammed in the passage behind you (thereby blocking your exit).

- There’s no one behind you who may get tangled in the line and have to cut it—leaving you with no guide home.

- There’s no one to accidentally disturb your ‘out tags’ at line junctions (e.g. in one cave there are 10 branch lines off the main line in the first 500 m/1640 ft of passage).

- There’s no one to cause silt problems (but yourself).

- There’s no chance of being called upon to share air—in small passages.

- There’s nothing to get confused about—communication in sumps varies from difficult to impossible.

- There’s no one to provide you with a false sense of security.

- There’s no one to worry about but yourself, so you can concentrate on your own safety.

Equipment Configuration

Due to the generally small passage size of British caves and the sometimes energetic nature of transporting equipment to a cave dive base (station), sidemount diving is the normal equipment configuration. Sidemount started in the U.K. in the 1960s with a need for streamlined and lightweight diving equipment. U.K. cave divers today will have a choice of sidemount harness for the project they are involved with. In a short, shallow, or constricted dive, the diver will use a wetsuit and a lightweight, webbing-only harness with no buoyancy, as it’s not needed if your chest is on the floor and your back on the ceiling.

In slightly larger cave passages, the modern British cave diver will use one of the now-common sidemount harnesses that are available. Many British caves require vertical cave techniques to reach the water, so the divers have modified the sidemount harness to be able to descend into the dry cave, do the dive, and then climb out. It’s very rare to find a British cave diver with an unmodified sidemount harness. For exposure suits, many short dives and some longer dives, if significant dry caving is expected before or after, the dive will be done in a wetsuit even though water temperature is on average between 7-10 degrees C/45-50 degrees F. This is for practical reasons, as it’s very difficult and potentially dangerous caving in a drysuit, so better to be slightly chilly during the dive and caving safely.

For larger sites and when the diver is expected to be underwater most of the time, a drysuit is sometimes carried to the dive base and put on underground, to be utilized for the dive. As most divers are solo diving, having two short standard-length hoses on their regulators is normal, although for team diving or cave rescue, a standard long hose is used on the right.

British cave divers always use helmets, as they provide protection from the environment in the dry caves as well as underwater, and are a great place to carry lights. Hand-held primary lights are used in larger, clearer passages with the helmet lights in reserve. For dive lines, we use 4 mm thick lines as permanent dive lines and we have fixed junctions in all caves— no jumps or gaps. Standard line arrows and cookies will not fit on a U.K. line. Pegs are used, or permanent markers on junctions to show the way home. It’s very unlikely you will see another dive team in the cave on the day you are visiting, and following a thicker line in sometimes low visibility and cold water is much safer and more comforting than trying to follow a technical diving line.

Exploring U.K. caves

The raison d’etre for the Cave Diving Groups formation was and still is the exploration of caves, including the surveying and reporting of that exploration and the training of new divers. The CDG publishes a journal four times a year with exploration reports and many books on the subject of U.K. caves and techniques. If it’s not surveyed and reported, it’s not explored. Now, it would be extremely tedious to the reader if I listed all exploration in underwater caves in the U.K.—we have thousands of reports—so I’ll mention a few of the classics to set the scene, and remember all exploration can be researched in the CDG journals.

If visiting, most U.K. cave divers are happy to show you around or even get you involved in projects, although they will be of a very different style of exploration than found in Bahamas or Mexico, for instance, where swimming into hundreds of metres of new cave is possible. Big breakthroughs in the U.K. are rare, and if a diver explores 10 m/33 ft of new cave with ongoing passage seen, they will be happy.

Wookey Hole Cave Somerset, Somerset

Exploration in the home of British cave diving started in 1935 and carries on to this day. Slow and determined work by some of the great names in cave diving, including Balcombe, Martyn Farr, Rob Parker, Rick Stanton, and John Volanthen have seen this multi sump cave reach 90 m/294 ft depth beyond chamber 25 in extremely committing passages. Smaller side passages throughout the cave are still being explored.

The Llangattock Cave Systems, South Wales

Under Llangattock mountain lies many kilometers of caving—two caves, Ogof Daren Cilau at 27 km long and next door Ogof Agen Allwedd at 32.5 km, provide access to many cave diving sites that have provided incredible exploration over the years and will hopefully provide more in the years to come. One of the longest dives in the system is the Pwll y Cwm resurgence at 630 m/2066 ft long, surfacing in the downstream end of Daren Cilau.

Kingsdale Master Cave and Keld Head, Yorkshire Dales

One of the true classics of world class cave diving is the Kingsdale to Keld Head system. Graham Balcombe, of Wookey Hole fame, conducted dives in 1945 in Keld Head, and in 1978, Geoff Yeadon and Oliver Statham broke the world record with an 1829 m/6000 ft dive between Kingsdale Master Cave and Keld Head, connecting the two caves. In 1991, the underwater system was further extended, linking it into King Pot cave access to the valley floor, a traverse of 3 km in British conditions. Today, divers continue to explore and extend this system.

Speedwell Cavern Main Rising, Derbyshire Dales

This dive site requires a reasonable amount of dry caving effort to reach the dive base. The dive itself is multi-profile with a descent to 36 m/118 ft then up to 2.5 m/8 ft via a constricted rift, then finally down to 71 m/232 ft at the end. In the 1980s John Cordingley and Russel Carter worked the site and finally, 71 m/233 ft was reached by Martin Groves in 2002. The way on was lost in boulders and boiling sand with the water surging upwards. This was confirmed by John Volanthen in 2006. A change in geology and future technologies await.

The Green Holes of Doolin, Ireland

In the years leading up to the 1980s, open water divers reported cave entrances in the sea on the Doolin coast. These completely submerged caves are extremely weather dependent due to taking the full force of the Atlantic Ocean. But after experience gained in the Bahamas’ Blue Holes, British divers tried their luck exploring what became known as Green Holes. Several sites including Reef Caves, Hell Complex, Urchin Cave, and the longest Mermaid’s Hole have had successive and continued exploration. 1025 m/3350 ft penetration being reached in Mermaid’s Hole by Artur Kozlowski. Exploration continues when the weather allows.

Swildon’s Hole Cave, Somerset

A true classic sump diver’s cave with long sections of active wet streamway takes the visitor down to a series of eight short sumps that require diving and more caving to reach the terminal sump and end of the cave at Swildon’s 12. Wetsuits and lightweight sidemount harness and small cylinders needed. A grand day out.

Porth Yr Ogof Cave, South Wales

One of the finest and reasonably easy physical-access cave dives in the U.K. The dive starts from a small pool after a short climb down between boulders. A shallow and comfortable passage winds its way up the valley passing Rawlbolt Airbell 150 m/492 ft from base and Four Ways airbell around 200 m/656 ft from base. At 250 m/820 ft from base, a cobble squeeze can be passed to the surface in the dry upper cave. The flow in this cave can be very high and the passage size varies from 1 m wide to 3 m wide, making progress upstream interesting and downstream on the return exciting.

Hurtle Pot, Yorkshire Dales

Probably the most dived cave in the U.K. due to its easy access and the possibility of longer dives upstream in a large passage towards Jingle Pot Cave and an area called The Deep reaching 35 m/114 ft depth in a low complicated passage towards the end around 460 m/1508 ft from base. Downstream a 400 m/1312 ft long traverse can be made to surface in Midge Hole cave reaching 20 m/65 ft depth on the way. This cave floods dramatically in bad weather, and constant line repairs need to be made by local CDG divers.

Peak Cavern, Derbyshire Dales

Peak Cavern is an extensive dry cave with several significant cave diving sites located within the system. The resurgence is a classic training dive in a lovely bedding plane style passage reaching the surface in the main cave. Ink sump within the cave, nearly 200 m/653 ft long, leads to Doom’s Retreat, an area worked by Jim Lister and the most extensive digging project to find a new cave beyond a sump in the U.K. Far Sump at 385 m/1263 ft long leads to an extensive dry section of cave with some extremely technical caving that can now get you to surface on the hills above.

Pollatoomary Resurgence, Ireland

Not many easy surface access cave diving sites that go deep are to be found in the British Isles, but this one in Ireland is one. A resurgence site that reaches 103 m/336 ft but in dark, unfriendly waters. Original exploration by Martyn Farr in 1978 and taken to 103 m by Artur Kozlowski.

In summary, British cave diving is historically one of the oldest branches of the sport of cave diving. The Cave Diving Group’s knowledge and standards and procedures evolved over the years to the safest method to explore or dive in U.K. style caves. It is not diving in Wakulla Springs and does not pretend to be, although several CDG members got involved in the early Wakulla expeditions. It is at times cold, wet, and unpleasant, but also can be extremely rewarding, with new caves found or just a superb dive in excellent conditions. U.K. style conditions can be found all over the world—think of the Thailand Rescue in 2018—and it’s in these conditions that the CDG system is at its best. If you’re wanting more information on the CDG or sump diving and vertical access sump diving, please give us a shout. Just remember—a pint of English beer is supposed to be warm. Stay safe and dive well.

Dive Deeper:

Website: The British Cave Diving Group

From GUE’s membership magazine QUEST: “British Cave Diving: Wookey Hole and The Cave Diving Group” by Duncan Price

Books about British cave diving:

A Glimmering in Darkness by Graham Balcombe

The Darkness Beckons by Martyn Farr

Interview with Cave Diving Legend Martyn Farr

Historical British cave diving films:

Trailer for documentary film ‘Wookey’ by Gavin Newman

The Underground Eiger (1980s)

Articles by Michael Thomas:

Slow Down Young fellas-Attitudes in Technical Diving

The Difference Between Caves and Mines

Michael Thomas’s diving career is now in its 33rd consecutive year, from starting out as an open water diver then a trainee cave diver to becoming the Training Officer of the British Cave Diving Group Somerset Section. He is also a Full Cave Instructor, Sidemount and Tech Instructor with TDI, active mod 3 CCR cave diver, and on the British cave rescue call out list as a diver.

Thomas is heavily involved in U.K. diving projects and training, plus overseas diving and caving. Diving is life or is life diving?