Community

My Deep Dive Into The Dunning-Kruger Effect

Tech diver Brendan Lund shares his personal diving journey from summitting Mount Stupid and descending into the depths of Despair on trimix, before finally beginning his ascent on the Slope of Enlightenment. No Kool-Aid was involved in the making of this story.

by Brendan Lund

Images courtesy of Brendan Lund

I started diving in 1996 as a poor student in South Africa. I absolutely fell in love with diving, and haven’t stopped since. After moving to the UK in 2001, I finally started earning money and was able to dive more frequently. At this time, the Red Sea was starting to boom, and I was able to book a full week of diving—including flight and accommodation—for as little as 350 GBP! Many trips later, I became interested in tech diving, as it was the happening thing, and in 2004 I decided to begin my tech journey with a leading agency. This also signals the start of my journey with the Dunning-Kruger Effect!

Grokking Dunning-Kruger

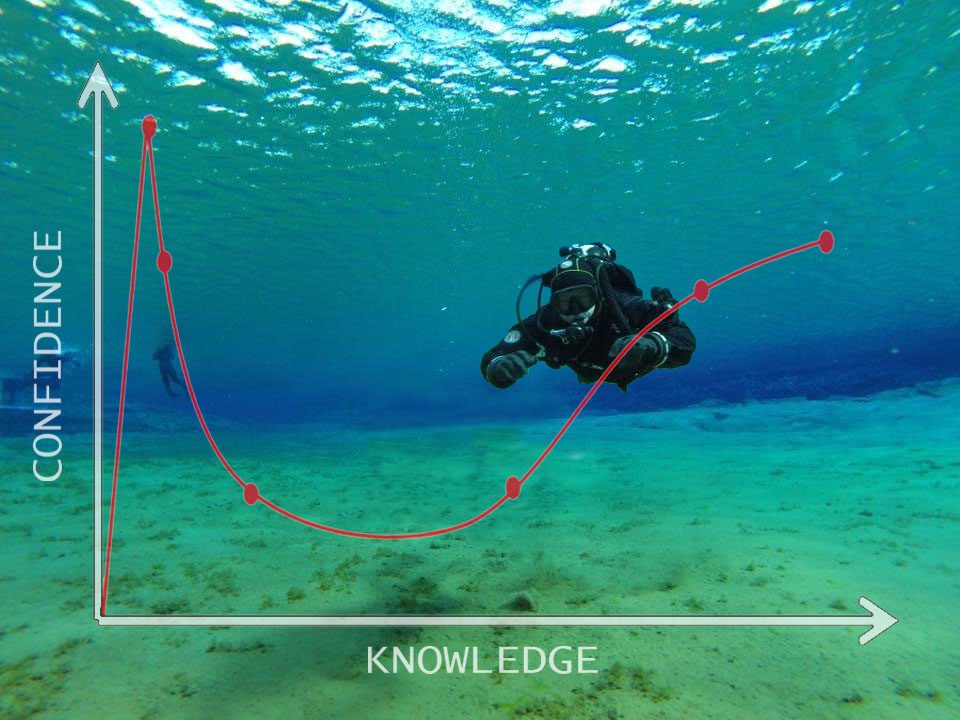

I first saw the Dunning-Kruger effect graph a year or so ago and couldn’t stop thinking about its relationship to my diving.

What is the Dunning-Kruger Effect? Here’s what Wikipedia has to say:

In the field of psychology, the Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. It is related to the cognitive bias of illusory superiority and comes from the inability of people to recognise their lack of ability.

As described by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, the bias results from an internal illusion in people of low ability and from an external misperception in people of high ability; that is, ‘the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others’.

The graph below simplifies this concept—again, this is taken from the internet, but the wording pretty much sums up what I have been feeling throughout this journey:

The less knowledge you have, the more confident you feel. The more you learn, the less confident you feel.

The View from Mount Stupid

In 2005, I progressed from an advanced nitrox diver to a fully-certified advanced trimix diver. My instructor was a well-known deep diver at the time, and I was super impressed with the courses. I was at the point of Mount Stupid on the graph. These courses were not a pass/fail style of course; you just had to prove you could complete the skill once, and bam! You’re qualified!

“Wow, I’m the man! I’ve passed my Advanced Trimix Course and dived to 100m.”

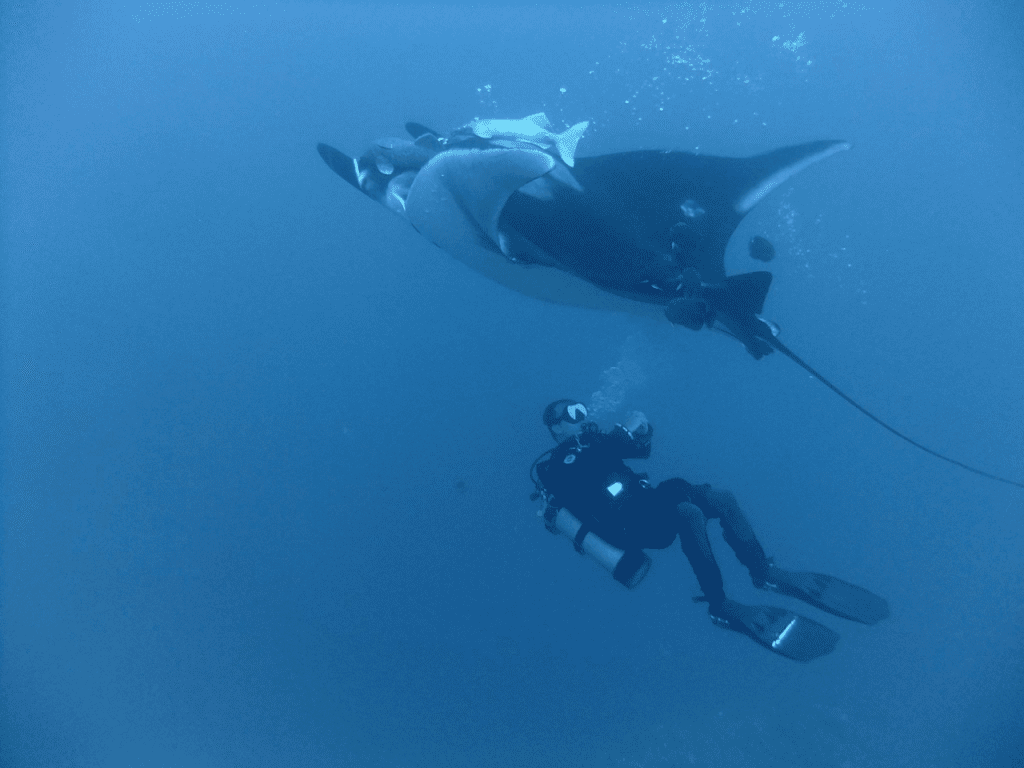

I dug out the photo below from a box in the shed. We had someone take an underwater photo of us celebrating our successful completion of our deco procedure course. As you may notice, trim was not a requirement at the time (I’m now hiding my face with embarrassment)! Apologies to my buddies in the photo; it was a while ago, and the instructor is the only one in reasonable trim!

To say I was chuffed is an understatement! I immediately went tech diving as much as possible. In 2008, I decided to travel the world for a year—diving of course. I met many amazing people and dived everywhere; I also became an instructor with a well-known recreational agency. I was at the top of my game (or so I thought), although I still don’t think I had any trim! I mean, who needs trim, right?

On one of my adventures, I met a guy who was really interested in checking out a new agency that he had heard of. This would be the first time that I heard about Global Underwater Explorers (GUE). After much research and reading internet forums for GUE in 2000, I believe the Dunning-Kruger realisation phase of my journey began: I thought, “There is definitely a lot more to this!”

The Slope of Despair

I’m not going to lie; the more I looked into GUE, the more nervous I got, and the more I slid down the slope of despair. It took me a good six years to build up the courage to sign up for a Fundamentals class, and I showed up on that day feeling very confident in my brand new drysuit and my horseshoe wing. Wow, did I learn that I was way out of my depth! I was in trouble. It was so much harder than I had ever imagined. I don’t think it was so much the course that was hard, but that it was hard for me to overcome my ego and overconfidence.

I received a provisional “Tech Pass” [i.e., I qualified to take GUE’s Tech 1 or Cave 1], and it felt like I had failed! I was at the bottom of the Dunning-Kruger slope of despair. Was I ever going to get it? I questioned whether I should go back to get my pass, and I have to thank my buddies Nikky and Darren for encouraging me to do so. After lots of practice and some gear tweaks, I felt like I smashed it, and achieved my Tech Pass! Was this the beginning of the slope of enlightenment? Things were starting to make sense!

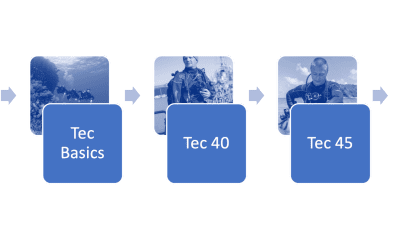

The Slope of Enlightenment

I have now completed two more GUE classes—DPV1 and Cave 1—and am signed up for Tech 1 next year. The future looks bright! I dive as often as I can with like-minded divers, and I realize that there is always more to learn and areas where I can improve. I am hopeful that I am now on the Slope of Enlightenment; it certainly feels that way.

I highly recommend GUE to any divers that would like to work on themselves. It has definitely helped me on my diving journey, and I now look forward to many more years of diving and learning. I can’t wait to get involved in more projects and extend my skill set.

Dive Deeper

It’s Never Too Late To Tackle Fundamentals

Brendan is an events manager based in London and (currently) dives mainly around the southwest coast of England. He started diving in 1996 in South Africa and has dived all around the world. He found a passion for cave diving a few years ago—his favourite place to do this is Tulum, Mexico—but still loves wreck diving. Brendan is looking forward to the next challenge, with project work planned with Project Baseline, and Tech 1 is in his diary for next year in Croatia, since Covid-19 postponed it this year.