Cave

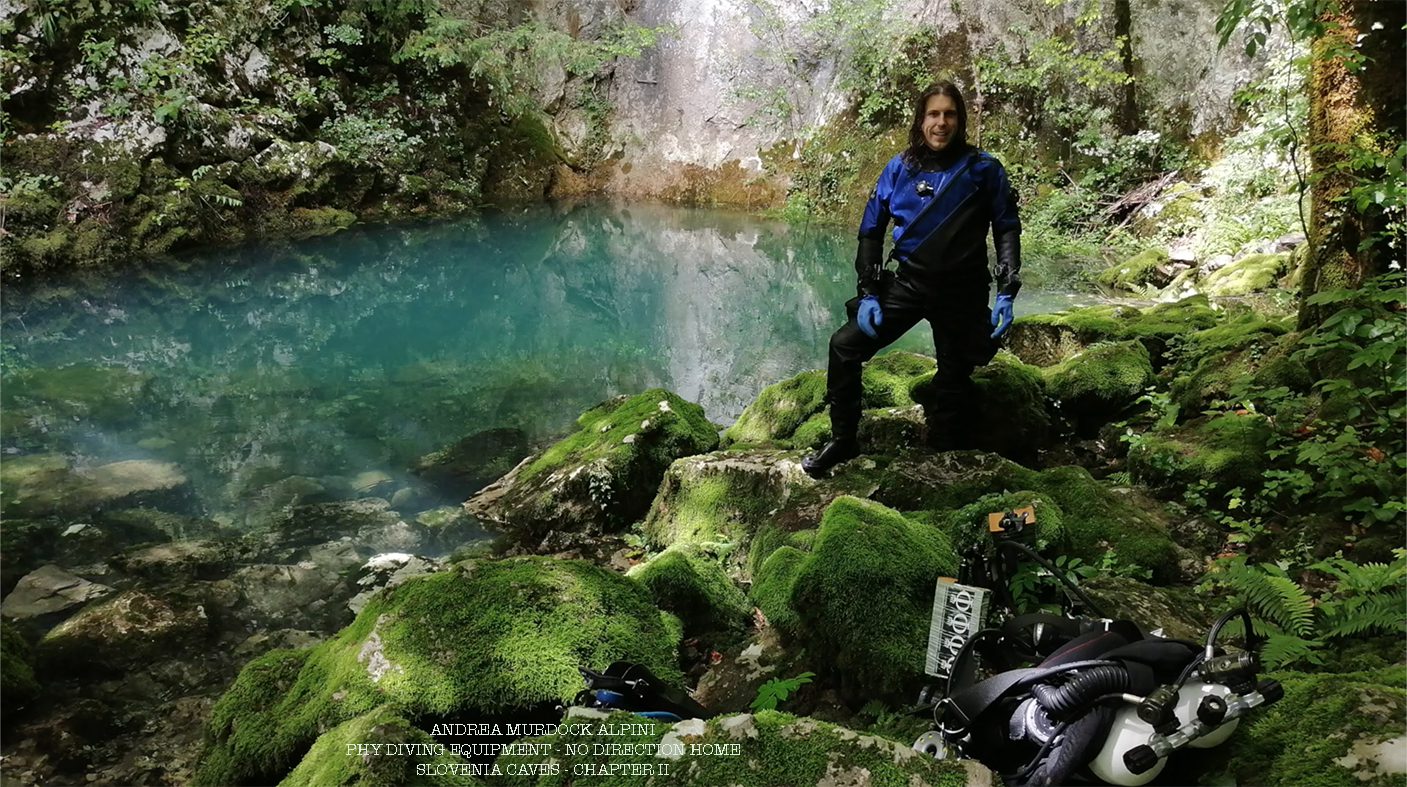

No Direction Home: A Slovenia Cave Diving Adventure

Suffering from Covid lockdown, young, poetic Italian explorer, instructor, and gear-maker, Andrea Murdock Alpini, decided to take social distancing to the max! He packed his specially designed cave-van and set out on a three-week solo road trip to dive the water-filled caves lying beneath the Slovenian soil. His report and must-see video log, dubbed, “No Direction Home”—an homage to Martin Scorsese’s Bob Dylan docu—will likely satisfy those deeper urges for adventure. Did I mention the killer soundtrack? Kids don’t try this at home!

Text: Andrea Murdock Alpini

Photo & Video: Andrea Murdock Alpini

Ecco la storia originale così com’è stata scritta in italiano

Author’s note: I do not encourage other divers to conduct solo diving. The trip and the dives described in this article were conducted after significant training and experience.

Ed.Note: Global Underwater Explorers does not sanction solo diving.

Freedom!

That was the feeling I had last June 2020 when I left my home to begin a journey alone. Caves, abandoned mines, alpine lakes, and a few wrecks—that was my plan for a great adventure.

The first COVID-19 lockdown had been in place for a couple of weeks, and I was afraid of going out and meeting people. Social distancing left an open wound. I loaded my wreck-van with plenty of stuff to survive alone for a long month traveling amongst rivers, lakes, mountains, and forests, and I was ready to practice scuba diving.

At that time, tourist travel was impossible in Italy or abroad—anywhere in Europe—because the coronavirus had locked the borders. I asked an editor in chief from a magazine—one whom I am used to sending articles to—to prepare a couple of official invitation letters for customs. For my trip, I converted my wreck van into a cave van. It was fully equipped with a 300-bar air compressor, helium, oxygen, deco cylinders, twinsets of different sizes, gas booster, fins, mountain boots, tent, camp burner, and brand-new dry suits, as well as thermal underwear to be tested for my company PHY Diving Equipment.

I remember the day well. I was thrilled as I crossed the border between Italy and Slovenia. I had been restricted to nothing but a 200 m/650 ft walk from my house because of the pandemic restrictions, but with an eight-hour drive, I was free to enjoy walking into wild nature all alone.

The mental switch was awesome, and unexpected. I did make just one phone call from abroad. I talked to an incredible Russian who was the first guy I met in a small rural village in Slovenia. He had emigrated some years ago, and now he welcomed travelers by sharing his farmstead.

However, once I arrived on site, I was not very welcomed by the weather; instead, I was met by heavy rain. After the storm passed, I went out walking and filming with my phone. I had decided to record all of the trip. As luck would have it, the rain returned again, and it never left me for the entire duration of my trip (almost a month).

My tour was articulated throughout Slovenia, Garda Lake (Italy), Austria, and South Tirol’s Alps, Tuscany’s caves, and finally I reached the central part of Italy—Appenini mountains and their peaks. I planned to reach two mines, but heavy rains stopped my dream. Excluding Slovenia, where I slept in a traditional bed, I passed all my time living in my tent. Cold weather and storms were my constant companions.

I managed to see a ray of light for just a few hours, I never had any chance to dry my equipment, and I warmed up inside my van. Every night I slept only a few hours because of loud wind noise or strong rain storms. Day-by-day I grew tireder and more feeble. One day, three weeks after I left home, I was in South Tirol descending a mountain when I decided to conclude my trip, and I returned home safe.

The goal of my trip was to tell scuba adventures from the surface point of view where the water is only a part of the context and not the objective. I made a mini-series film composed of three chapters. Each one brings you inside the scene. What follows here is the first episode of the trip.

Social Distancing Beneath The Slovenian Soil

The first day of cave diving in Slovenia was very tricky and full of adventures. I had no idea how the second day would go.

I left my accommodations around 6 a.m., after a good breakfast of cereal, dark chocolate with black coffee, dried fruit, and tasty Italian Parmesan cheese. I could not see anything from my window because what had fallen was not simply rain; it appeared to be an awesome flood. My plan for that day had been delayed.

I think that most parts of dry caves are condemned for hundreds of kilometers. So, I decided to check the weather forecast and water level conditions in caves close to the Croatian border. It would mean driving about four hours to see for myself whether scuba diving was allowed. I didn’t have to remind myself, I was alone here.

Wheels were on the road and local conditions seemed quite good. I had checked the weather on my laptop and understood the risk. If I was lucky, I could dive; if not, I would have to drive back. I drove through Slovenia forest meeting no one. With less than an hour left to my destination, I came across an abandoned farm village, completely empty.

The dive inside Bilpa Jama was breathtaking. Now I was seated beside the cave shore preparing soup to warm myself. After a stunning solo dive, I was cold and wanted only to taste the peace of this magnificent place. While I was dipping the spoon in my soup cup, I heard a faraway voice, a police woman calling me and asking me to stop eating and come quickly to her.

After I did as I was asked, she started examining my passport, documents, and permissions. A few minutes later, a huge National Army truck reached us. The soldier had an abnormal body shape, a man the size of a walking mountain in an Army uniform. Can you imagine how I was feeling in those moments?!

Well, in the end, everything went really well, and I now have a story to tell my grandchildren.

Once the passport control was over, and they had checked that I did not cross the border from Croatia to Slovenia illegally (customs was only a few hundred meters from us), I had the chance to get back to my soup, which by then had turned cold. I warmed it up again, and I spent half an hour seated on a slippery stone covered with moss and lichens watching the beauty of the forest surrounding me.

On the way back to my accomodations in my cave van, I played a new playlist.

Four hours later, I approached my country lodge. I was really exhausted, but I had to refill tanks and plan the next scuba diving days. Once I finished, I watched the forecast again. Unfortunately, it was growing worse, so I decided not to dive and instead get a surface break. Tomorrow I would drive, search, and catch info and GPS coordinates of caves. My tomorrow plans had turned into a sketching and surveying day.

The Road To Suha Dolca

I drove and walked for hours and hours, up and down the forest or on lonely roads in search of caves where I could return in winter or perhaps next year. During the last survey of the day, I watched a talented young guy playing a traditional concertina and thought, what a lovely atmosphere and a fitting way to close my hard-working day!

I decided to give a last gaze to Suha Dolca cave, my favorite one, on the way home. This was the third consecutive day I had arrived back at this spot. Observing it day-by-day, I tried to find the best moment to dive this cave.

Until now, it was inaccessible due to the strong flow. I wanted to dive here before leaving Slovenia. Tired and driving slowly, I parked my van away from my accommodation. Since I had no lunch, I started feeling very hungry. A simple dinner was quickly served: dried fruits and a cup of hot noodle soup.

My ‘NO DIRECTION HOME’ trip was now at its peak. I had become a wanderer. I was alone in a wild country with, yes, an internet connection for historical research and checking the weather. That was the only technology I used. Aside from that, I lived simply. I walked, dived, wrote, and filmed my experience all with my mobile phone.

Rain was tougher than expected. I had hoped to stop for one day, not the two that it took. Following the surveys, the next day I started fixing my video equipment and saving photos and videos I had made on my hard drive.

I had too many ideas, no one clear till the end, and too many cave sketches and GPS points to reorganize; I needed a day to regroup. I just went out for a few hours to check Suha Dolca’s Cave conditions. On this day it seemed that the flow was getting more stable, and general water conditions were growing better. I had to be patient and wait one or two days more for the right conditions. I tried and failed to find a solution on my own, but the water always showed me the way. She told me to wait and to go back to where I came from. Step-by-step I walked the path again.

The third video chapter of Slovenia Solo Cave Diving is the one I prefer, because I remember the indecision I felt, to stay or to leave. Solo trips are strictly linked to life’s decision.

The last day I was in Slovenia I left the accommodations and asked a new farmer, close to a different cave, if I could sleep inside his barn and dive the river hole on the following day. I was at the same place where I had dived the first day. He told me I could not stay in the barn due to the high risk of bears who live in the surrounding area. I jumped in my van again and I drove to the lake beside Suha Dolca’s Cave.

I descended the path several times and brought all my scuba gear piece-by-piece. I decided to give myself a chance to dive my dream cave in the late afternoon. I had no other choice. Once I was inside the cave it was unbelievable, and I had a very nice dive even though I was really tired, and again I broke my light arms and camera housing. I resurfaced after the dive into a reed’s lake, which made me feel like a beaver.

I had conflicting feelings as I left Slovenia that same night after making a tricky and stunning dive. Bears, awesome forests, and rural areas were now all behind me. The cave-van played a new disc, I needed to shake off these feelings and look forward to my new goals: Garda Lake’s wrecks, South Tyrol’s stunning lakes, and finally Austria. In the country of green and wide grazing land I wish to dive surrounded by the amazing scenario of beautiful Alps mountains.

At 9:30 PM I crossed the border again, and Italy was straight ahead.

Andrea Murdock Alpini is a TDI and CMAS technical trimix and advanced wreck-overhead instructor based in Italy. He is fascinated by deep wrecks, historical research, decompression studies, caves, filming, and writing. He holds a Master’s degree in Architecture and an MBA in Economics for The Arts. Andrea is also the founder of Phy Diving Equipment. His life revolves around teaching open circuit scuba diving, conducting expeditions, developing gear, and writing essays about his philosophy of wreck and cave diving. Recently he published his first book entitled, Deep Blue: storie di relitti e luoghi insoliti.