Community

Nourishing My Inner Tekkie At Bonaire Tek

What goes on when you bring together a group of 80-some enthusiastic tech divers, provide boats and beach access, rebreathers, doubles and scooters, ply them with plenty of helium, nitrox, oxygen and sorb, nightly brain food and then turn them loose—sans gloves—on some of the most bodacious reefs on the planet? Here InDepth editor-in-chief Michael Menduno tells all, well almost, of what went on.

by Michael Menduno

Header photo by Matthias Leno courtesy of Buddy Dive Resort

Where is Bonaire? That’s the question that diving friends were still texting me as I boarded my plane for the eighth annual Bonaire Tek gathering—a week-long tech diving love fest held 6-11 OCT on the small island of Bonaire in the Leeward Antilles, in the southeastern Caribbean. The island—technically a special municipality of the Netherlands—along with Aruba and Curacao, form the ABC islands located 80 km/50 mi off the coast of Venezuela, and is known for diving, windsurfing, and sailboarding.

I was on assignment for InDepth and looking forward to meeting German Arango a.k.a. “Mr.G,” who oversees the technical diving program at the Buddy Dive Resort, which hosts the event. Sporting long wavy hair and a salt-n-pepper beard, the 45-year old Colombian-born tech diving instructor who teaches primarily for GUE, as well as for NAUI and PADI, was responsible for conceiving the idea for Bonaire Tek and has organized the event for the last eight years. “My goal is to build a community here,” he told me when he picked me up at the airport.

And he is succeeding. Bonaire Tek, which is sponsored by Dive Rite, SubGravity, SANTI, KISS Rebreathers, and Silent Diving has grown each year since its inception. This year there were 81 divers—57 men and 24 women—from 11 countries, including North and South America, Europe and Australia representing 52 open-circuit (OC) and 29 closed circuit rebreather (CCR) divers.

The concept of a tech diving “camp” embodied by Bonaire Tek, the pioneering TekCamp held at Vobster Quay in the UK, Underworld Tulum’s Cave Camp, and the Ponza Rebreather Meeting in Ponza, Italy, has proven itself to be a fantastic vehicle to engage geeky divers in tech, and help spread the love. To wit, bring in a manageable-sized group of avid tech divers of varying experience levels, provide plenty of awesome diving, an opportunity to take courses, try-out new gear, share stories, enjoy depth-full talks on various aspects of diving, eat, drink, meet new friends, and hang with the tribe.

To be sure, Bonaire Tek, which ran from Sunday through Friday, didn’t disappoint! There was a communal breakfast every morning, followed by dedicated OC and CCR tech boats and a variety of shore diving. There were people who came simply to dive, and others who were taking courses. In the afternoons there were additional boats and dockside try-dives on AP Diving, KISS, O2ptima and xCCR rebreathers, various side mount rigs and SubGravity scooters. In the evening, we gathered for one or more talks, and dinner and drinks. Rinse and repeat.

Bodacious Bonaire

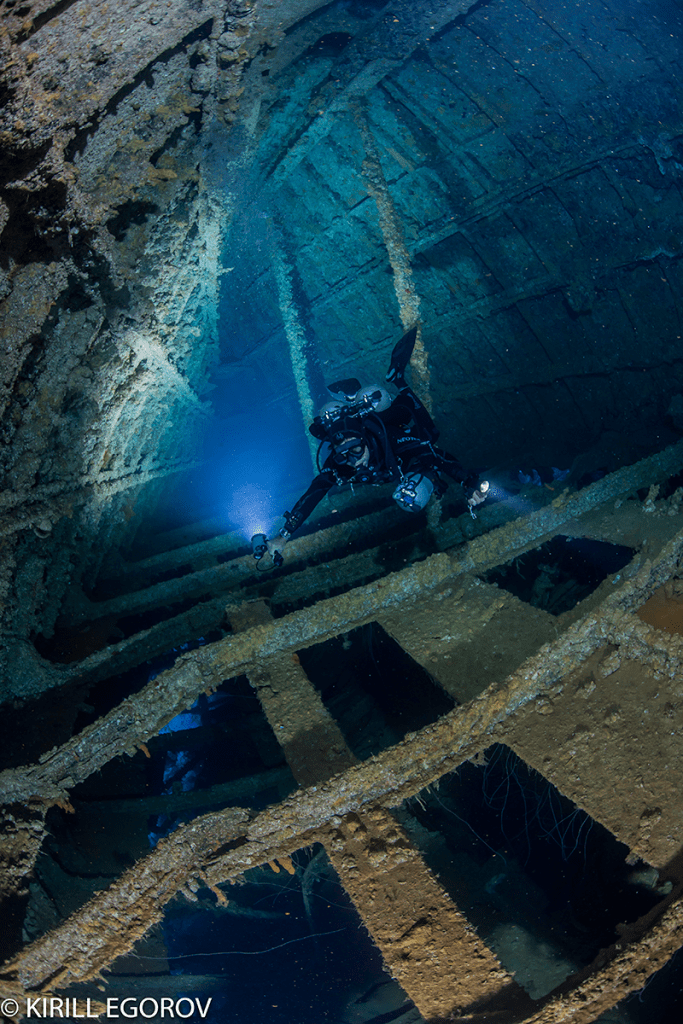

Pulling my nitrox 50 deco while gently gliding along the phantasmagoric wall of boulder-sized coral heads amidst hundreds of bright colored reef fish, following our mix dive to the wreck of the Windjammer more than 50 m/163 f below, gave new meaning to the notion of Caribbean reef diving! More surprising, we conducted the dive from shore. The water was consistently 30 C/86 F at the surface and dropped to 27 C/80 F at around 50 m. Visibility was in the 30-40 m/100-130 f range, and they tell me the reefs are almost always diveable. It’s easy to get spoiled by Bonaire!

In recreational diving circles, or maybe it’s the island’s tourism bureau, the island is known as the “Shore Diving Capital Of The World!” For good reason. On the leeward (diving) side of the island, which is approximately 39 km/24 mi long by 5-8 km/3-5 mi wide, the reef and drop-offs begin within a short swim from shore (windsurfing and sailboarding are prevalent on the windward side). The same is true of the even smaller island, Klein Bonaire, which is nestled in the leeward embrace of Bonaire, a mere 800 m/0.5 mi swim away. From the air, the two islands look like an amoeba swallowing a bite-sized morsel of food!

In fact, dive marketing mavens have identified more than 80 dive sites along Bonaire’s leeward side. As cardiologist and tech instructor, Doug Ebersole, one of the presenters, put it, “Where else can you make a 200-foot plus wreck dive, followed by a wall dive and see sailfish blennies?” Bonaire!

According to the amicable and animated Mr.G, the reefs are near pristine for several reasons. First, is the arid island’s low population density—there are only 20,000 permanent residents on the island, little rainfall, and no agriculture. Read: minimal impact population pressure and little chemical runoff.

Second, the Dutch have long instituted conservation measures; the island was designated a marine sanctuary in 1979. As Mr.G instructed the assembled divers during his initial briefing, “Whatever you do, don’t touch or take anything; gloves are not allowed!,” he said, giving a new twist to the old urban meme, “NO GLOVE, MORE LOVE!”

Buddy Dive also supports the Reef Renewal Foundation Bonaire, headed by local marine biologist and tech diver, Francesca Virdis, and they host part of their nursery on Buddy’s Reef, which begins 20m/64 f from the dock. The island is also known for its wild donkeys and flamingos.

Bodacious Buddy Dive

Much of the success of the event was due to the dive-oriented venue and the amazing support provided by Mr.G and his team. Located right on the water’s edge, and offering 24/7 diving, Buddy Dive Resort is arguably a bit of diver heaven. Eleven yellow stucco buildings with spacious, clean, air-conditioned apartments, patios to dry dive gear, two pools, a dockside dive service center, and 24/7 accessible wooden airy dive lockers and tanks—no surcharge for banked nitrox 32, along with a drive-thru fill station. There are also two restaurants, car rentals, laundry service, and drinkable de-salinized water. All you have to do is dive!

Providing daily diving support and gas for 81 enthusiastic tech divers is no small task, and Mr.G’s team of divemasters and gas blenders handled it with aplomb, albeit with little sleep—the fill team pulled multiple late to all-nighters. Divers were assigned individual numbered cylinders including their singles, doubles, stage bottles, and CCR tanks, which were filled to meet their daily gas needs in an area called the “Tech Block.” It likely represents the largest gas blending operation in the Caribbean. That’s where divers picked up their cylinders, analyzed, and labeled them for the day’s diving.

Buddy divemasters, many of whom had been GUE trained, provided diver support on the daily boats and typically accompanied dive teams. We were even joined by head of dive operations for Buddy Dive, Augusto Montbrun, who with his team, spent a morning supporting two teams of tech divers.

Bonaire Tek Stats

Tank Fills: 2100

Liters of helium consumed: 180,000

Liters of oxygen consumed: 324,000

Liters of banked nitrox 32: 1,000,000

Kilograms of sorb: 360 kg/792 lbs.

Number of dives conducted: 660+

Hours underwater (est.): 550+

Hours of decompression(est.): 225+

Deepest dive: 107m/350 ft

Big Smiles: 81,000

Celebrating Our Tech Sisters

The theme for this year’s Bonaire Tek was “Ladies First,” helped by SANTI, and fittingly the gathering had the largest female turnout yet, representing roughly 30% of participants. Yay!

Argentinian tekkie Marcia Gallego’s festive dive themed nails.

Accordingly, Mr.G arranged for several female-focused presentations beginning with a homage to “Female Tech” presented by Buddy Dive’s PADI Course Director and tech, cave and CCR diver, Lars Bosman. His presentation began by recognizing early diving pioneers, such as Simon Melchior Cousteau, Dottie Frazer, Zale Perry, and Dr. Sylvia Earle. He then went on to profile contemporary tekkies like explorers Jill Heinerth, Verna Van Schaik, and Immi Wallin, photographer Becky Schott, shark whisperer Cristina Zenato, stuntwoman and model Szilvia Gogh, Helene “Wethorse” Graauw, who invented the “She-P,” and Bonaire’s own Virdis.

Ebersole followed a few nights later with a presentation entitled “Women’s Issues in Technical Diving.” After offering a disclaimer that he was “NOT a woman,” he proceeded to discuss the science on decompression sickness (DCS) and gender, DCS and menstrual cycles, diving and pregnancy, breast augmentation, DCS and birth control pills, menopause and more. He later wrote up his talk, which we will publish in the December issue InDepth.

Mr.G had also arranged for morning yoga and core-building exercise sessions which were enthusiastically attended by humans of both genders. Interestingly, they also tried to arrange for a women-only boat dive day, but there were no takers, even after repeated attempts, to the apparent surprise of the organizers. One female observer noted women want to be included, not set apart.

Steeped In History

Bonaire Teksters, whose average age was likely pushing 50, were offered a trio of diving history presentations over the course of the week. On our first night, we were treated to a talk, “Maritime Archeology in Bonaire” by Dutch marine archeologist, Ruud Stelton PhD. He explained Bonaire’s early history, initially as a cattle plantation for the Spanish in the 1500s, and later, in the 1600s, a plantation of the Dutch West India Company supplying salt used for preserving food to Europe on the backs of slave labor. Salt continues to be Bonaire’s largest export today, and salt fields are visible in the north, as well as the huts where slave populations lived. Moorings, abandoned anchors, and artifacts can also be found.

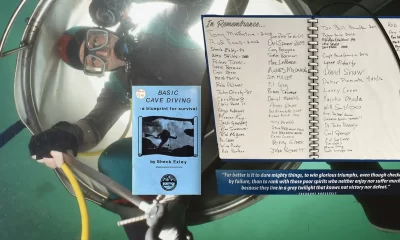

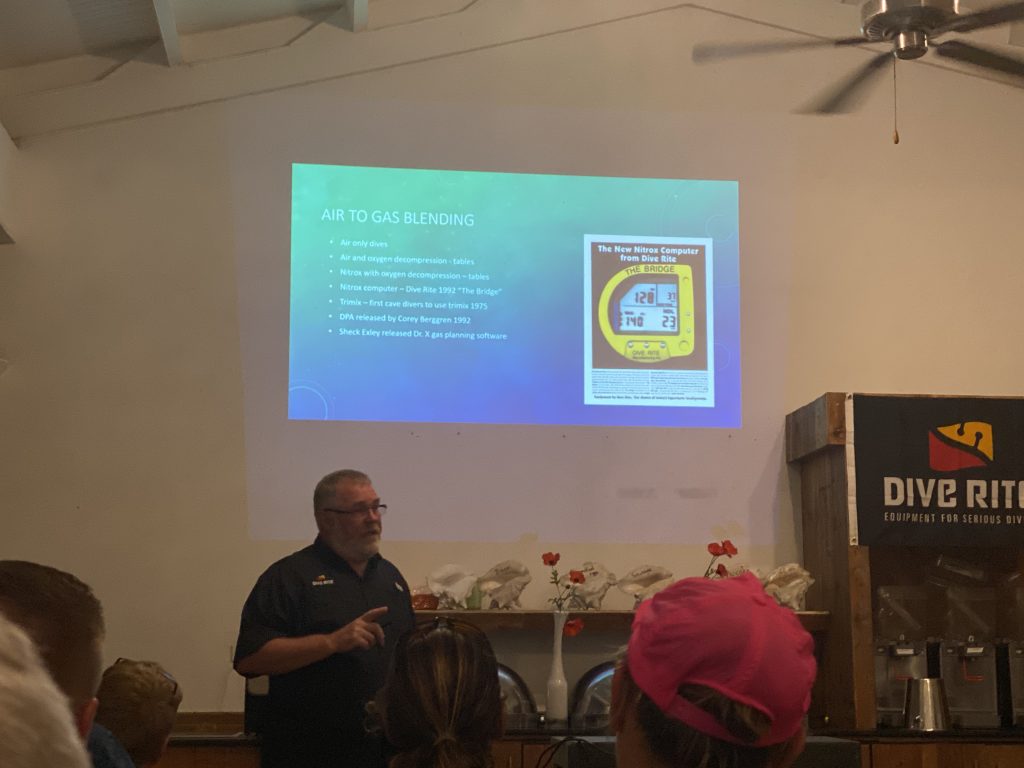

Dive Rite founder and cave diving pioneer, Lamar Hires, regaled us with tales of some of the early developments in cave diving with his talk, “Cave Diving: Mission Specific.” He began by explaining the early 1980s development of sidemount with cave diving pioneer Woody Jasper, regarded as the “father of sidemount.” At the time, the test of a good cave diver was to the ability to swim to the Hinkel restriction (975m/3200 f) and back to Ginnie Springs on a set of doubles.

As Hires explained, part of their motivation for diving sidemount was finding cave that the “big boys” hadn’t yet explored. That would be famed explorer Sheck Exley and Woodville Karst Plains project (WKPP) co-founder Bill Main. “We knew if it required sidemount, Sheck and Bill hadn’t been there,” Hires said with Mona Lisa-like smile. He also discussed the skepticism that greeted the first isolator manifolds as a result of three cave diving fatalities. Of course, isolator manifolds eventually became the standard.

Hires went on to talk about their first use of oxygen as a decompression gas (instead of simply using it to pad their air tables) at Cow Springs in 1986. Hires and his team were able to incorporate oxygen because anesthetist John T. Crea and his company’s Submariner Research Ltd. computer program was able to cut air with O2 tables, requiring them to pull their oxygen stop at 9 m/30 ft. It was a fascinating talk.

I also gave a two-part talk, “Revisiting The Technical Diving Revolution: An Insider’s Look at the People, Projects and Technology that Created Technical Diving.” In it, I discussed the emergence of tech diving in the mid-to-late 1980s, the development of “special mix” diving, nitrox, the origins of the name ‘technical diving,’” early tech diving fatalities, the persistence of deep air, and the development of consumer rebreathers. Call it a “history stop!”

Joys of Team Diving

The diving is what brings people to these events. I was no exception.

I made my first shake out dive of the trip with Bosman, who took me to what he said was one of the best reefs on Bonaire, called Lac Cai, on the windward side of the island. After negotiating our rocky beach entry with doubles and a pair of SubGravity Ecos S DPVs, we conducted a luxurious 75-minute dive along the length of the breathtaking reef wall max depth 23 m/75 f surrounded by bands of sea turtles, rays, and large silver tarpon. It was a sublime beginning to a glorious week in the water.

I am currently getting re-certified for mix diving, and in the process of completing my GUE Tech 1 (normoxic helium diving) training. As a result, I was excited about spending the week diving with friends from Team GUE Seattle, who had a contingent of ten, including a non-GUE rebreather diver, as well as some recreational divers.

Though not everyone’s cup of tea (mind that Kool-Aid!), I have a growing appreciation for GUE’s standardized approach to diving—standard config, gases, deco, protocol. It puts everyone on the same page so they can focus on the main goal: Having Big Fun!

The T1 class is all about underwater problem solving while maintaining one’s buoyancy and trim in the water column, and most importantly one’s COMPOSURE. After all, just like nitrox, breathing helium is easy, you just breathe in, and then breathe out. The induced problems we dealt with in class included resolving bubbling first stages and manifolds, out of gas situations, non-working deco gas, and failed mask, which occurred one at a time or in combinations, for example, while shooting an SMB.

So imagine my glee upon descending on our first dive to see my dive buddy, photographer Matthias Lebo, with first stage seal bubbling. I knew what to do. I immediately swam over to affect a fix by trying to screw down his left post. To no avail. Full disclosure: I had forgotten my lesson; valves don’t move when pressurized. (I’m sure Gareth Lock, Mr. Human Diver, has a reference for me: fact retention). Argh! Not to worry. My teammate Bert Brezicha reached over, checked that Lebo was breathing from his right post, shut down his left, purged the reg, tightened the valve, and powered up the post. No bubbles, no troubles; we were good to go. I will never forget that again!!

Though I was skeptical at first, I have come around and really appreciate GUE’s team or operational approach to deco, which again makes things easy and keeps the dive team together. I suppose it’s ironic, that just like the early days of tech, GUE dives tables instead of computers, in this case generated by DecoPlanner software (based on Buhlmann Z-16 and or VPM-B algorithms). Dive computers are there as a back-up though not really needed.

They also use standard gases such as Trimix 21/35 (21% O2, 35% He) for depths from 30m-45m/100-148 f, trimix 18/45 from 45-60M/148-197 f etc., and deco gasses like nitrox 50 and oxygen, which makes things easy. In Bonaire, we were primarily diving nitrox 32 or trimix 18/45 for deep dives with nitrox 50 for decompression.

What’s more GUE modifies its deco procedures to make them easy to carry out as a team using only gauges. So instead of everyone chasing their own dive computer, we ascend as a team to our first stop at a 9m/minute rate (30 f/min), depending on the dive make our gas switches to say nitrox 50 at 21m/70f (team-based gas switch protocol) and proceed to work our way back to the surface.

Rather than stop for example for one min at 21 m, one at 18 m, two at 15 m, two at 12 m, three minutes at 9 m up and then say 20-minute at the 6 m stop as calculated from DecoPlanner, GUE-ers average their stop times so they stop two minutes at each stop from 21m to 9m and then pull their required 20-minute deco at 6 m. The resulting plan? “Twos and 20!” Easy to remember, and easy to conduct. In fact, that’s the deco we—the shallow team—did on our Windjammer dive to 50 m/164 f with 20 minutes bottom time. Deco on deeper and longer dives get a little more complex.

Modify the numbers from the deco algorithm? Is nothing sacred? The argument being that the algorithms i.e. one minute here, two minutes there etc. are just an approximation anyway; decompression is not (yet) a precise science. In fact, according to a recent DAN Europe study, 94% of hits occur within the specified table or computer. GUE’s thinking: better to prioritize team unity and operations. See Jablonski’s article “Decompression, Deep Stops, and the Pursuit of Precision in a Complex World, Part Three; Bubble-wise, Pound Foolish.”

A final lesson in protocol: We were running late. I was waiting for my gas; doubles with 18/45, and a nitrox 50 stage. Team Seattle was waiting for me. I finally got my tanks, analyzed my gas, got labels, filled them out hurriedly, and then inadvertently mixed up the labels. I put my 50% label on my doubles and the 18/45 on my stage. I didn’t notice. However, my GUE teammate, anesthesiologist Heléné Pellerin did. “Michael, your labels are incorrect. You must re-analyze your gas,” she said with no uncertainty in her French Quebec accent. “No problem. I’ll just write new labels, “ I answered, not yet realizing where this was going. “No,” she said, “you must re-analyze your gas.”

WHAT!#@? I just did. OK, I was a bit perturbed but reluctantly reanalyzed my gas; didn’t want to push the point with my new team. The gas hadn’t changed, and this time I correctly applied the new labels.

With later reflection, I realized my tech sister was absolutely right and I was glad that she spoke up, and that I complied. Do you know how many of our tribe have died breathing the wrong gas at depth? Answer: Way too frigging many!

I’m reminded of a recent post that the human Lock recently re-tweeted—a post from Lt. Gen. David Morrison, “The standard you walk past is the one that you accept!” It’s a matter of building safe habits and a fail-safe system to catch our humanness. I mean I knew what was in my bottles, but if someone else had used them, for whatever reason, they wouldn’t, would they? In fact, after that I made it a point to ask Heléné when I had a question of protocol or procedure. She was always helpful.

Ironically, we shared the tech boat with a NAUI Tec team from Argentina headed by NAUI greybeard, Daniel “Dani” Millikovsky, along with instructor Ken Head from Texas. I learned that they were also diving their own standard config, standard gasses, and runtime tables generated by RGBM algorithm. They wrote their runtime schedule down on the wrist slates. Completely different from GUE of course that mandates Halcyon WetNotes!

Just kidding! It was clear to me that our commonality greatly outweighed our differences, and we had a number of enlightening in-depth discussions—the subject of a future article.

Community Safety

SubGravity and TEKDive USA cofounder Randy Thornton appealed to our higher angels in his talk, “Make Tech Diving Great Again.” He began with a startling statistic that the average time that a new tech diver stays in the game is two years! The Reasons: they never get truly comfortable with gear, and/or being in the water, and yet they often push themselves to do too much too fast, resulting in too much stress—all of which is NOT fun. “At the end of the day, we are here to have FUN,” he reminded us!

Thornton, who is a very experienced tech and CCR instructor, offered sound advice: learn progressively, gain experience at each level before moving on, pick the mentors you want to emulate, keep an open mind, and show up at classes ready to learn. He admonished instructors to maintain their integrity and to say, “No” if their student was not ready for the next class.

GUE Seattle deep-diving team exiting the water after diving on the Windjammer.

Not one to preach what he doesn’t practice, Thornton, who during his pre-diving career put in his 10k hours as a professional musician, shared that he takes a new class every year and makes it a point to dive with other age groups and training agencies. “Mastery is just a momentary point in time,” he observed. “It’s the process that’s important.”

Finally, he thoughtfully reminded us about the use of social media and implored us to just say “NO” to cyberbullying. “We need to be sharing information and knowledge and celebrating each other’s successes, not running each other down,” he emphasized, offering mountain biking forums as an example of communities that are doing it right.

Here was my favorite anecdote in his talk:

There was a farmer who won the award for the best corn year in and year out. A reporter discovered he shared his seed corn each year with his neighbors. “How can you afford to share your best corn with your neighbors when they compete with you each year?” the reporter asked. ‘Why sir,” said the farmer,” Didn’t you know that wind picks up pollen from the ripening corn and swirls it from field to field. If my neighbors grow inferior corn, cross-pollination will steadily degrade the quality of my corn. If I am to grow good corn, I must help my neighbors to do the same.

In other words, you have to give it away to keep it! Thornton ended with a depthful plea, “Share with others through mentoring and giving back, and help build our community.” Amen.

Silent Diving’s founder and president, Mike Fowler, gave the final presentation titled, “How Do We Make Diving Safer?” He began by reviewing the grim statistics on rebreather diving deaths; 317 deaths from 1998-2018, 146 from 2010-2018 or about 16/year. Fifty-five percent were solo diving, 30% failed to monitor their sensors and or ignored warnings, 30% conducted poor assembly and pre-dive checks, the list goes on.

Fowler then discussed the role of “human or non-technical factors” in these incidents and offered the Rebreather Education and Safety Association (RESA)’s 10 Point Plan. One of his comments stuck with me, “If there’s any doubt, there is!”

Sadly, a very visible and loved member of our community who was an experienced rebreather diver, anesthesiologist and hyperbaric doctor Fiona Sharp died in Bonaire on a solo rebreather dive, a few days after the event ended, in what appears to be a result of human factors. See the accompanying article, “Fiona SharpYou Will Be Sorely Missed!,” in this issue.

To honor our dear sister’s passing, Mr. G has decided to dedicate next year’s Bonaire Tek 2020 to improving diving safety. It’s something we can’t get enough of. Hope to see you there next year.

Dive Deeper

Award-winning underwater cinematographer Matthias Lebo, who is based in Zurich, Switzerland, produced a series of videos of the event. The Croatian born filmmaker spent most of his twenties traveling the world – primarily Australia, South East Asia and Europe – working as a Scuba Diving Instructor, intensifying his love and appreciation for the ocean. Lebo operates a small film production company named “Liquid Images.” He’s made it his mission to show as many people as possible the beauty and wonders of the underwater world. He hopes to raise awareness of how fragile our marine ecosystem is. You can also find him on Facebook. Enjoy!

Bonaire Tek Final Recap Vid of the Week

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s executive editor and, an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine “aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving”(1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012, and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018.