Community

One Way The World Learns to Mermaid: The Mer-spective from PADI’s Karl Shreeves

InDepth’s editor-in-chief Michael Menduno reached out to PADI veteran Karl Shreeves to explore the trending global phenomena of mermaiding….

by Michael Menduno

Header image and photos courtesy of PADI Inc. unless noted.

InDepth’s editor-in-chief Michael Menduno reached out to PADI veteran Karl Shreeves to explore the trending global phenomena of mermaiding, which may well surpass tech diving in terms of sheer numbers in the not so distant future! While you shouldn’t expect to see a Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) “MER 1” class anytime soon, it’s fair to say that mermaiding is here to stay—and that’s arguably a good thing. Here’s why!

As a uniquely dominant force in the $3-4 billion worldwide sport diving market, with nearly 6600 affiliated dive centers and resorts and over 128,000 members, it’s not surprising that privately-held PADI Inc., the self-proclaimed, “Way The World Learns To Dive,” is one of the most closely watched and talked about companies in the business.

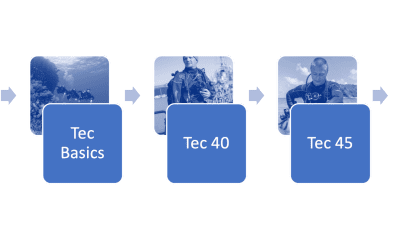

Over the last thirty years, since the emergence of technical diving, PADI has arguably relied on others—“Brand X” in PADI parlance— to bring technological innovation to the diving market while keeping a careful eye on their progress. Once a sufficient market develops, PADI moves in to adopt, standardize, promote, and profit from the innovation, and help popularize and fuel its growth by virtue of PADI’s sheer scale, often to the dismay of competitors. It’s a tried and true model that the organization has applied to nitrox, open-circuit tech diving, recreational rebreathers, and recently even freediving.

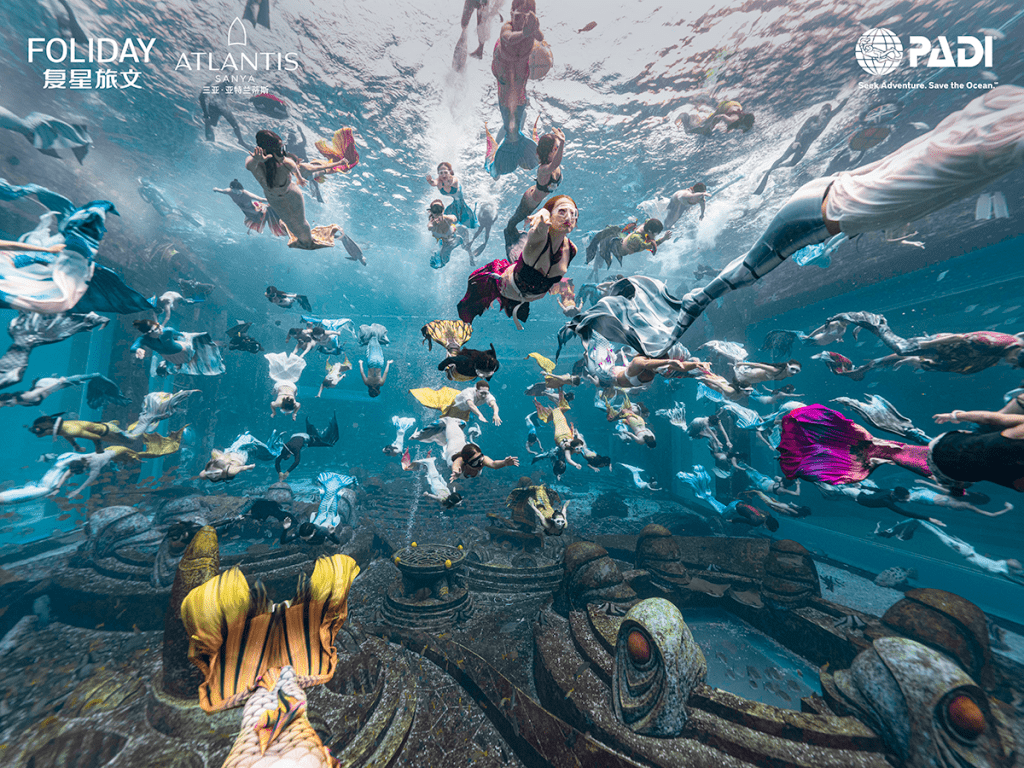

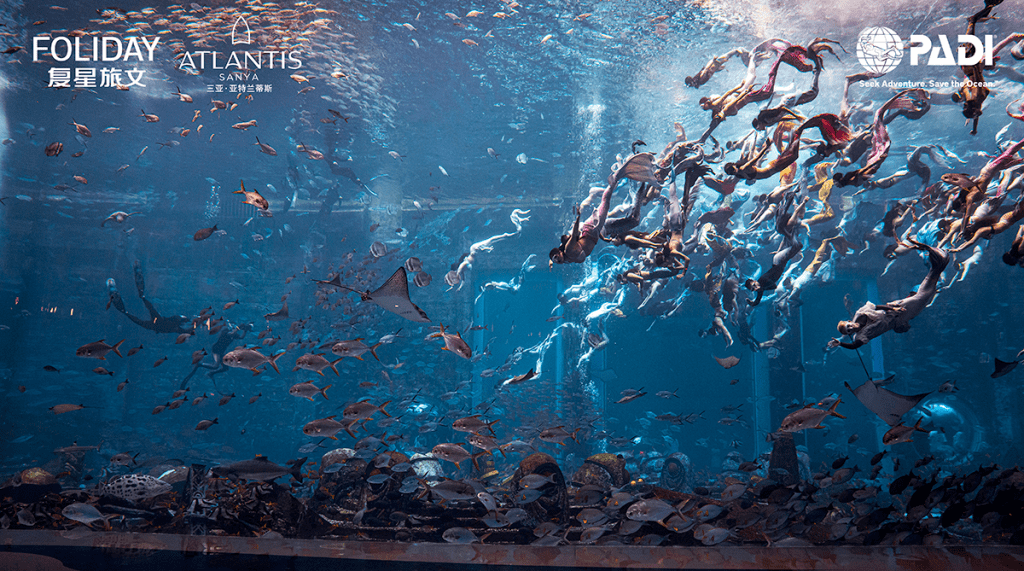

So, it was perhaps inevitable, given the tremendous growth and interest in mermaiding over the last decade, along with the entry into the market by Scuba Schools International (SSI) and NAUI, that PADI would pick up the tail, er trail, and offer its own mermaid program aimed at aquatic consumers, and its own teeming instructor ranks. Τhe fifty-five year old training behemoth launched the program in December 2020 and kicked it into high gear last April, with a TikTok-savvy, mano-a-mano, Guinness World Record extravaganza —the largest mermaid show on Earth—held at the Atlantis Sanya hotel aquarium, in Sanya China. Cirque du Soleil move over!

Accordingly, to get a perspective on the market, we reached out to PADI’s original tekkie, technical development executive Karl Shreeves, who helped field its mermaid program, and was instrumental in the development of PADI’s nitrox and tech diving courses. Here’s what the veteran educator had to say.

InDepth: To start, let me ask you: How did PADI get involved in mermaiding? When did you start looking at it and thinking about creating a training program?

Karl Shreeves: PADI had actually gotten involved with mermaiding several years ago. We had several instructors who had become part of the existing mermaiding community that wanted to offer a distinctive specialty. So, they submitted the distinctive specialties outlines, and we approved them. And then it started to grow, and the interest started to grow, and we began to get calls for us to create a program like we have for freediving and scuba diving and other types of diving.

So, we started developing that in 2018 into early 2019. At the time, for us, and by us, I mean what was then the mainstream diving community apart from mermaiding, it was pretty small potatoes. Mermaiding already existed. It popped up on its own track separately from diving. There were already mermaiding schools and people doing it who did not come from a diving background at all. They just got into mermaiding.

Did things slow down with the pandemic?

On the contrary. The interesting thing was that the pandemic seemed to propel it. And the reason? What do water enthusiasts do when they can’t travel? They get into the local pool. The pandemic helped freediving as well, and in some areas, local diving did well. Scuba divers quickly figured out that, “Well, I can’t see as far in my local lake as I can in Grand Cayman, but it’s actually pretty cool.” They get a trained eye and a perspective.

But as the pandemic forced us to stay closer to home, there was a growing interest among the traditional diving community in this form of diving because, unlike freediving and scuba diving, all of a sudden, there was an expressive form of diving. It’s underwater dance. The costumes are beautiful. Obviously, it borrows from other kinds of diving. They all borrow from each other, right?

But you know, especially if you were going to be primarily in a pool, it gave water enthusiasts a new craft that is well suited to the swimming pool. While there is open water mermaiding, as you know, a lot of it is purely in a swimming pool or the various dedicated super pools, and it’s a really good fit there. So mermaiding is a new angle, if you will, for expressing yourself.

It’s a performance art in many ways, like synchronized swimming or water ballet.

Right. Of course, there are a lot of people who come from the diving side and they say, “Well, it’s a form of freediving.” But really, it’s not.” It shares a lot from freediving. It has borrowed a lot from free diving, but it’s really different.

Freediving tends to be more about the performance of depth and duration. It’s an athletic accomplishment. And again, there’s overlap. I’m speaking a bit in absolutes, but don’t misunderstand me. Mermaiding is more about individual expression and fantasy made real—an ability to touch people in a way that goes as far as wearing make-up as well as some elaborate costumes. And yet, having to be able to swim. And not just swim, but to look elegant and interact with people.

That’s where it’s got an appeal because that hasn’t previously existed much in diving. Probably the closest thing would be being an underwater model. Ironically, because of the pandemic, and lock-downs, I wasn’t able to be one of the shooters for our Mermaid eLearning course. If there was ever a shoot I wanted to do it was that one!

Ha! You were deprived! What about the language? You use ‘mermaid’ to refer to both genders, not mermaids and mermen, or merfolk?

Funny you ask about “mermaid” as a term, because we actually explain it at the beginning of the course. “Mermaid” denotes gender in English, but in many languages the translated term means “human fish” and doesn’t indicate gender unless you add words to do so. Some in mermaiding use the terms “merfolk” and “merman” etc., but broadly, “mermaid” is the term everyone knows. So, the PADI materials use “mermaid” in the sense of “human fish” as in languages like Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. But obviously, it’s not a female-only sport by a long shot. Lots of men are mermaid divers and PADI Mermaid Instructors.

I’m sure some of our readers see mermaiding as a trend, something new, but the concept and fascination with mermaids goes back a long way.

It’s not new. It goes back over 1,000 years. There is something about this idea of a human fish that has endured. If you look at the movie Splash, right? 1984. The sixth largest grossing movie in China was The Mermaid. And they are talking about a sequel now. The Korean drama I keep talking about, Legend of the Blue Sea, is one of the most successful dramas they’ve had. Very popular, and people still watch it aftermarket and buy it on DVD. So, this is not a flash in the pan. It’s actually a cross-cultural mythology that we’ve enjoyed as humans. If it were just one culture you’d say, eh… But it’s not.

Every culture independently created this myth. Now the modern mermaid tends to be the European mermaid, and we talk about this in the course too. Why? Because it’s practical. The European mermaid’s bottom half is fish and top half is human. Very easy to create a swimmable costume. But some, you can do it with computer graphics, it’s a fish with a human face. But my point is that when we look at this as the dive community and say, “Oh, that’s just a bunch of people playing around.” Yeah, it is, but that’s not new. This has been around. So this is going to stay. Now that we have the ability for people to go play mermaid in a serious, fun way, they are going to keep doing it because it’s cool.

In some ways, it enables us to reach back through time and connect with this myth that’s embedded deep in the human psyche.

Once humanity starts to picture something, we find ways of making it happen. And that’s what’s happened to the thousand-year-old dream of being a human who can live in water. We found a way to make it real.

Talk to me a little about the size of the market. Obviously if PADI is getting into it, you must think there is sizable potential. I was surprised when I attended the ADEX show in Singapore in 2019, and they had a huge mermaid section. In fact, it was bigger than the tech diving section! They had 30 or 40 famous mermaids there. I didn’t know who they were, but the people knew them and cheered for them. It was amazing.

Well, as I said, parts of the dive community had adopted mermaiding. It was already growing globally. In fact, it’s really big in Asia in terms of its visibility, but there’s actually a pretty strong community around the world. There are communities in Europe. Here in California, they have a small mermaid convention that’s been held for several years in the Bay Area. It’s not huge but it’s there, and quite separate from diving. It’s about mermaids and mermaiding. They get in the water; they talk about mermaid stories and myths. They role play, and there’s also a little bit of cosplay. Ι think that is part of the fun for some people.

But to give you an idea of scale, when we finally launched the full version of the program within, I want to say, it was a month or two months, we had 500 instructors.

Wow. That’s surprising! Evidently there’s a lot of pent up demand.

Right? When you pick up that many instructors that fast, it’s two things. One, it is popular. Two, it’s already widespread because you don’t learn to mermaid and then reach instructor qualification in two months. You actually have to already have the qualifications. And what we’re seeing is two prongs of appeal.

First, it’s opened the eyes of divers who’ve never looked at it before and are most certainly going, “That’s cool.” A lot of them are free divers, but some of them are scuba divers. They’re like, “I want to give that a go.” But then we are also seeing that it’s pulling from the original market—people just interested in mermaids who want to live out the fantasy, as it were. That gives it a lot of youth appeal, especially among younger children.

What we’re finding is that attraction is growing because some of these people realize that it also brings them a connection to diving. It’s like, “I’m not only going to become a mermaid, but, if I want, I can grow towards becoming a diver as well.” Some people find that out in the course. Because, as you might expect, a lot of the mermaid instructors also have their fins in the freediving camp. Those people tend to do a really good job of instructing because they know the difference. They know the difference between mermaiding and freediving. So, they don’t try to make mermaid divers freedivers, but they do train the mermaids in the techniques that apply from one to the other.

In fact, somebody was asking me about this. “Oh, it’s just a form of freediving.” And I said, “No, not really.” However, when you are a buddy, that is the safety diver in mermaiding, that’s when you’re closest to being a freediver because basically you have the same job.

Makes sense. Freediving has developed safety techniques and protocols, which I would imagine apply to mermaiding too, so that mermaids don’t blackout underwater?

Yeah, in fact mermaiding basically borrowed that most directly. So, while mermaids don’t do static apnea, they swim dynamically as free divers call it. In other words, there’s lots of horizontal movement, but depth isn’t too great. Of course, the more experienced ones still get down there pretty well. But as soon as you shift—”Okay, it’s my turn to be the buddy.”—the mermaid tail comes off, the mask goes on (which is optional if you’re the mermaid), and you wear bi-fins because you need to be able to help and maneuver quickly in the event of a problem. So, that’s probably where you have the most and the strongest connection to conventional freediving.

Mermaids wear monofins but they use bi-fins when being a safety?

Right. They are required to use bi-fins for safety because they need to be fast and maneuverable as a safety. But by definition, if you’re a mermaid, what kind of fin are you going to have? I suppose somebody might come up with a bi-fin mermaid look, but basically, it’s all monofin. They’re going to learn both to be successful in the course.

In freediving, they have the one up, one down system, or one up, one prepping, one down in a team of three, in order to rescue the diver in case of hypoxia. So, mermaids also have somebody watching them who is ready to intervene when they’re holding their breath underwater?

Exactly! Freediving has done a lot for all breath-hold diving, just like tech contributed to all scuba diving. Tech taught us to be tighter with teams and also offered a mindset and approach that has been picked up. The alternate air source originally came from tech. Likewise, freediving has influenced breath-hold diving, even basic snorkeling. Divers are taught that they have to take the snorkel out of their mouth when you’re doing a breath-hold dive, so you don’t breathe a lung full of water in the event of unconsciousness.

Nope! That applies to snorkelers as well!

Of course, if you’re old school like me, and you came up the other way, as soon as you start freediving you’ve got a habit that you’ve got to change. The habit you learned first is the one that sticks. In instructional psychology we are still trying to figure out why this is. Of course, new divers are getting the right habits from the beginning, so they’re not going to have to relearn them.

Yeah, I had that problem too. My freediving instructor had to keep reminding me to spit out my snorkel when I dived! You mentioned open water mermaiding. I’m familiar with mermaid performances but do they also go out and conduct mermaid dives? Would a mermaid say, “Hey, let’s put on our tails and go dive the kelp forest?”

Because there is so much crossover between the communities, you have people who enjoy mermaid diving, and this is what we covered in the advanced mermaid course. They go out and they mermaid in the open water. There can be many motivations.

There are certainly venues, you know the classic going back decades is Weeki Wachee, of course, where you can watch. And that is more serious mermaiding. Just put brackets around it. It’s a little different from what a recreational mermaid learns. But it’s still the idea.

Mermaids like to be in a natural environment and watch each other. If you are somewhere warm and nice—like Grand Cayman or Bonaire—and you are surrounded by beauty, it’s fun to go mermaiding. And if you’ve got underwater photographers who might want to take pictures of you, all the better.

Are you aware of the Korean drama, “Legend of the Blue Sea?” It’s set in Korea but it begins somewhere in the mid-Pacific. The actress who plays the mermaid is swimming around coral and gorgeous stuff. The story is about how she swims all the way to Korea. So that was the performance. In recreational mermaiding, they have fun doing this. It’s something that can be done together in nature. In that case, they typically wear masks so they can see clearly, and they’ll swim down and see the fish. So, it’s a neat little aspect of mermaiding.

That’s right, you need a dive mask, not swim goggles, because you wouldn’t be able to equalize.

Right, and that’s another area where mermaiding differs from other forms of diving. The mask is optional. Some people prefer them, and or wear contact lenses that need to be kept dry. Conversely, in a place that’s not going to bother the eyes, where you see well enough to navigate, some will forgo the mask altogether. In the China video, you saw both.

Let’s talk a little about what has been in place prior to PADI’s and other training agencies’ entrance into mermaiding. How did people learn to be mermaids? I do know there are several schools out there like the LA Mermaid School, and I think Weeki Wachee has a program as well. That’s likely some of it.

Well, it’s kind of all over the map, like what you see in most swimming programs or water programs. There are numerous mermaid schools, as you call them, and there would be a ranking of typically a beginner and then an intermediate level and so on. I would say that—and I want to be sure I’m talking generally here because there are exceptions all over, things are starting to solidify, and community standards are evolving. However, generally compared to what diving offers many mermaid programs were comparatively unsophisticated but safe as far as I could tell. I saw nothing that looked unsafe. Some of them were pool-only and you always have grown-ups there, because there are children in the program, things like that. On the other hand there are some very sophisticated professional mermaid schools like LA Mermaid School and the Weeki Wachee program that offer top notch professional training.

I think what diving has brought to mermaiding is our experience in water safety and integrating it with breath-hold diving. If you take a PADI program, for example, and you are going to be a mermaid diver, you don’t need to be anything else. You just need to be okay on the medical (as any diver of any type), have basic swimming ability, and we’ll take it from there. You don’t have to be a “diver.” You’ll learn what you need to know to be a mermaid, which includes the stuff that’s come over from the other forms of diving.

I looked at the requirements. You need to be able to swim of course.

Yeah. And if you get right down to it, almost all water sports have that. If you fall in the water, it would be good if you knew how to swim. Seems like a good basic safety concept.

Ha! I also thought it interesting that your mermaid programs were open to pre-teens.

Yeah, it’s breath-hold diving, we don’t have the concerns we have with scuba. There’s not a risk of lung overexpansion injuries. We’re not concerned with the kind of depths that limit the junior divers to about 21 m/70 ft. On top of that, this is where we are able to borrow from the community that was there before we got involved. Traditional mermaid courses brought in kids. Kids do this great. They love it. They’ve already been doing it. So it’s not like we had to craft something new to make it fun for kids. Kids already know it’s fun.

We talk a lot in our industry about getting more young people into diving, given the increasing average age of the scuba diving community. Looks to me like mermaiding has the potential to get more young people underwater which is what we want, right?

Absolutely, but also what you’re describing is Western-centric, and changing. We are seeing more young people getting certified. But when you go to the Eastern Hemisphere, it’s like our generation was when we were in our 20s and 30s. That’s who is going diving, the young people. And it’s huge, and I would say it’s much more social there as well.

The ADEX shows are filled with young people. It’s a very different demographic than the US or Europe.

There is a senior crowd there as well. Interestingly, for a long time PADI Japan was top age heavy because of the demographic of their country, but now that is changing as more young people get involved.

Traditionally, Asian cultures have been better at revering the older generation than Western cultures, because they recognize that’s where wisdom lies. So, you bring the innovation and the enthusiasm of youth, and you pair it with the wisdom and lessons of the past. That’s where you get a really strong community. You can probably tell: I really admire that they bring that to our diving community.

PADI has a bazillion dive centres around the world. Are we going to start seeing mermaid programs and communities popping up everywhere?

I would say yes. It’s happening as we speak. I mean it has never happened before: a program was a fringe program, a specialty, that was going to be it. The market was that small. But like I said, the pandemic changed that like it changed so many things. We’ve never seen a program that went from essentially a fringe activity to something worthy of our full support with e-learning in a year and a half! I’ll tell you what, I’ve never had to type so fast in my life.

To me it’s exciting. It’s like, wow. Because diving could either have fallen on its face during what happened or it could do something new. And we’ve done something new. I mean it wasn’t “new new,” but it was new in the expansion and the attention it got and that caused it to grow. The community is even plugging into dedicated deep pools like K-26 in Korea, one of those purpose-built deep pools that goes down to 26 m/85 ft.

Ah yes, deep pools. We have a story about deep pools in this issue.

There are a number in Europe, and there are some being planned for the US. Mermaiding blends beautifully with these. Because it’s more than a pool but not quite open water, but you’ve got the controlled conditions, and you have depth. The freediving community has taken advantage of these, too. Most of these facilities have underwater windows as well. So now, in addition to performance art, you have the potential to make it a spectator sport, if you will, in diving.

Yeah, that’s really interesting. Talk to me about training. We will, of course, include links with the article about your courses etc., but tell me, what do you need to learn to be a mermaid? What is the main focus of the courses?

As I mentioned, a lot of it is stuff you’d learn as a freediver, but applied to mermaids. The first thing you learn is about the costumes because that’s a little different. What is or is not an appropriate mermaid tail? Because you can buy some out there that are purely costumes, they are not for swimming. You learn to swim in them, so there is a huge emphasis on dolphin kick. You learn breathing techniques. But again, as a mermaid, you may not have a snorkel or whatever so you learn how to float, you learn how to wade as a mermaid. At the same time, you are also learning to be a safety buddy. What do I have to watch? I’ve got to have these fins on, things like that.

Is mermaiding a team activity built around two or three people mermaiding together?

Like other forms of diving, you can’t paint too tight a box around that. But what we teach is that you have somebody watching you. It wouldn’t be considered reasonable to have two mermaids on the bottom and one safety diver. But if you were diving in threes, say, one person would go down and then come back up and then another goes down and comes up, and then the third, so it’s a bit like free diving. In open water, the safety diver might escort you through the last 5 m/15 ft. But in pool-based mermaiding, just like in pool-based free diving, the safety diver just stays on the surface.

They learn skills that were developed in freediving but have been mermaid adapted. Like doing a duck dive, which is a little bit different in a tail than in bi-fins. You learn some skills unique to mermaiding. There are more flourishes. Like C-shaped turns and back turns and the mermaid kiss. All these things that they love to do. Team handshakes. They get into the performance a little bit.

The instructor also has the latitude to help the mermaids try the makeup. And again, it’s not your typical Mary Kay. It has to be two things. It has to be waterproof and then if you’re in open water, it has to be environmentally friendly. It can’t be something that would hurt the environment. In our program, the mermaids are taught about the environment and our role as stewards, and they are encouraged to join the community of torchbearers who are trying to speak for the oceans.

You incorporate ocean and water conservation!

Yeah. All our programs have that tie. If you love the ocean, you can see what’s happening. You can also see that we can do something about it. And the most important thing right now is we all have a voice and a purpose when we come together on that.

I’ll run slightly into the weeds here, but you may have heard a few years ago that Drew [PADI CEO Drew Richardson] committed the PADI family to one billion torchbearers by 2050. And that’s actually not that huge a number. Drew also didn’t just pull that number out of the air. When you look at social tipping points, the amount of the population that has to adopt a new view before society tips in that direction, one billion is about half that number.

That’s a laudable goal!

So, obviously, when we start talking to mermaids, a lot of those folks are a crowd from outside our normal sphere. Of course, we want them to understand about the oceans and have a connection to it.

They are ambassadors. They are performing for people who may not be water people.

The potential for a mermaid to get in front of non-divers is in some ways better and at least different. And so they are reaching a new audience. Look at Mermaid Linden . How many kids does she talk to? You start talking with her about the ocean, and you won’t leave without knowing that it’s in trouble, it’s worth saving, and we can do it. She’s reminding six-year olds that they can help.

That’s powerful. I don’t know that the scuba community even talks to six-year olds. Get them while they are young, right? Karl, you and your colleagues have been involved in the development of many, many training programs. Was there anything unique or challenging about creating a mermaid program?

I’d say, fortunately, we’ve done this enough that we have learned where to look. In the past, I would’ve said that the challenge might have been finding the experts that we needed to go over what you’ve done and help us look for gaps and things like that. I would say, if there was any challenge, it would be this, and that was when we got to the e-learning part.

Because of the lockdowns and everything we were very limited in what we could do in terms of finding talent and locations and photographers. We always try our best to show as much multicultural diversity as possible in our products, but this one had to be shot entirely by our China team. We were able to get some stock photos and so on to show more than Asian faces, but you can tell, if you look at the program, that they handled the imaging for us.

But I’ll have to say, if we had to have a challenge, I’ll take that one any day of the week. They did a great job with what they did. They found some really, really talented mermaids to act in the stills and videos. We found enough stock shots of other faces that we could show our diversity. Plus, anybody who knows us, knows that we are probably the most culturally diverse group in diving.

PADI is not the only agency to see an opportunity. SSI launched their mermaid program in 2018. NAUI launched theirs in 2020. As far as Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) is concerned, I don’t expect to see “MER 1” anytime soon. But who knows? Do you anticipate more agencies jumping in on the tail wagon, as it were?

Yes, I believe we are going to see others pick this up as well as it grows. Success breeds competition. It’s happening, but that’s cool.

I remember once asking undersea pioneer Phil Nuytten, who invented the modern one-atmosphere suit, if he expected to have any competitors. He told me, “I hope we have competition. In fact, I hope we have a lot of competitors. Because if we don’t, it means that it wasn’t a very good idea.” I’m guessing that the people at SSI and NAUI are at least feeling validated!

Competition also keeps everyone sharp!

All the better for the mermaids, right? You launched your program in December 2020, and then last April PADI held this huge extravaganza in China. It was what, the largest underwater mermaid show ever?

The event was held at Atlantis Sanya in China and it set a Guinness World Record in their giant aquarium. It involved more than 100 PADI Mermaid divers, plus support divers and topside personnel. The divers spent three days rehearsing a synchronized dive—you can imagine what it takes to get 100+ divers to descend at the same time and then swim in a coordinated manner. It was spectacular though—and had a lot of international coverage.

I heard that the event got 170 million views on TikTok—OMG!—and PADI now has something like 600 mermaid instructors and 50 dive centers in China offering your mermaid program.

I don’t know the numbers off the top of my head, but yes, the PADI Mermaid Program has gotten a lot of attention around the world. More than 600 instructors in China alone sounds right – it’s been eye-opening.

Talk to me a little about technology. Do your courses deal with working with surface supplied gas, or scuba, or the use of nitrox as a pre-breathe? Would that be technical mermaiding? Ha!

It’s not within our program nor any of the programs you’ve mentioned, to my knowledge. It wouldn’t surprise me if we get there. Now I do know that the Weeki Wachee program, which has been around for years, is training professionals. There you have to be a scuba diver because you are going to breathe compressed air, if I am not mistaken. Of course, you have to know how important it is to be exhaling as you ascend. Exactly the opposite of what you would normally do as a free diver or mermaid diver. Right now, that kind of thing is outside of what recreational mermaiding, for lack of a better term, is about. But come ask me again in a few years. I’m serious. We saw freediving do it, right? You just said it—technical free diving. Whoever thought, oh, I can breathe up using a gas with a high oxygen fraction and stay down longer on my one breath. That’s helpful. Who knows? One of the cool things about diving is that divers tend to get what they want instead of what someone thinks they ought to want.

I was speaking to Virginia Hankins at the LA Mermaid School and SHEROES Entertainment that provide professional mermaids for film and photoshoots and professional engagements. They are trained to use underwater breathing equipment. She’s one of your instructor trainers.

Yes, absolutely. We were talking about “Legend of the Blue Sea” earlier, and I’m sure it was true in “Splash”—when you start talking about Hollywood productions, they are going to use scuba. Again, that’s beyond what we are teaching in our recreational program. It requires additional education.

Let’s talk about equipment. I attended Eric Albinsson’s webinar on PADI mermaiding. He said that the global mermaid tail market was valued at $80 million in 2020—that’s annual revenue, and was expected to grow to $150 million by 2026, a compound average growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5%. That blew me away!

I don’t know what number he’s quoting, but it’s definitely there. And again, it’s not new, if you think about it. In our courses, the minimum is a monofin. But look at the variety of tales in that China mermaid video.

They’re exotic and amazing. Some of them look like a real biological tail!

Yeah, so there’s absolutely a market that’s growing. And it’s been there, but it’s accelerating. And again, the pandemic probably helped it.

Obviously, PADI sees this as a business opportunity, not just for itself, but for its dive centers, instructors, and professionals.

Absolutely. For one thing, it’s reaching a new market, and some of these people will likely get exposed to freediving and scuba. So, you get this neat cross-pollination of the three markets, or rather the three communities. The second thing is, it’s a great resource to use. If you have a pool, or if you go to a pool a lot, you can do a lot there. People can go all the way through mermaid without going to open water. So, the center can offer two full certifications, plus the experience. If I ran a dive center, I would definitely at least be dabbling in it right now. I don’t think I’d want to ignore it.

It seems to me it’s a lot like adding freediving to a scuba center.

It’s similar. Your upfront investment isn’t that high. If you’ve got an instructor who wants to get into it, that person trains up and they learn to teach. You don’t need to buy another compressor or a mixed gas blending system. If you’re already catering to freedivers, you’ve already got all that covered. So basically, you’re talking about adding mermaid tails.

Tails! There we go again. I’ve often thought our job as an industry is just to get people into the water. Create water enthusiasts and then they’ll find whatever pathways work for them. Mermaiding is another fun thing to do in the water.

Last question: Where do you see this going? Where will mermaiding be ten or fifteen years from now?

Boy, that’s such a hard one to call because if you had asked me that question a year and a half ago, I would’ve said, “Well, maybe we’ll have a supplemental program someday.” And here we have a full e-Learning program we’re about to debut.

I don’t want to call this one. It’s going to grow. I can say that with confidence because it’s got the inertia now, it’s already happening, it’s already popular, and it’s global. There’s attention to it. It’s beautiful, it gets people in the water. There isn’t a whole lot to say against it. So, it’s going to be bigger. How much bigger? I don’t know. It could really take off in some communities that have not been connected to diving, where that visual appeal is important, and there are a lot of young people involved.

Thanks Karl. Call me crazy, but I find all of this really interesting.

Dive Deeper:

The Darker Side of Mermaids:

Wired: Fantastically Wrong: The Murderous, Sometimes Sexy History of the Mermaid

The Filthy Mermaid: Got-To-Have-Goods for For Mermaids Gone Bad

Events:

MerFest International 2021 (South Haven, MI 20-22 August, 2021)

Mermaids In Paradise (Ramrod Key, Fl 15-22 September, 2021)

Training:

NAUI: Fantasy Becoming Reality – When Divers Become Mermaids

PADI: How To Become a Mermaid

SSI: Join An SSI Mermaid Program

Michael Menduno/M2 is InDepth’s editor-in-chief and an award-winning journalist and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for more than 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine “aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving” (1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving and he produced the first tek.Conferences and Rebreather Forums 1.0 & 2.0. In addition to InDepth, Menduno serves as an editor/reporter for DAN Europe’s Alert Diver magazine, a contributing editor for X-Ray mag, and writes for DeeperBlue.com. He is on the board of the Historical Diving Society (USA), and a member of the Rebreather Training Council.