Community

Technical Diving Myths vs. Reality

Greek cave instructor and filmmaker Stratis Kas explores some of the unstated myths about tech diving and offers up some hard-won consensus reality.

By Stratis Kas

Header photo in Sardinia by Mariona Yepes Daviu / Bluforia.

While many highly-trained divers have the knowledge and experience needed to face the very real challenges that technical diving offers, some do not. The idea that all technical divers have the advanced skills needed for their dives is a myth in the industry–one that needs to be acknowledged and addressed.

Let’s start at the beginning.

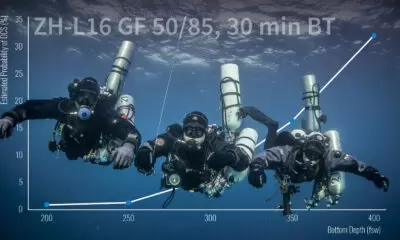

All technical divers know what they are doing about decompression

Technical divers are supposed to not only manage, but also to understand, and therefore agree with the diving plan that they are “choosing” to follow. They need to have a deep, extended, and in-the-field experience of all the factors affecting their chances of survival. That means really understanding decompression theory and how and why to use gradient factors. Relying on machinery means you’re not diving your plan and you’ve handed the responsibility for your safety to an expensive piece of equipment. It happens all too often.

One of our main concerns as divers is not even entirely factual. Deco theory is (still) a gathering of data that applies to a mysterious physiology and complex reacting unit, the human body. Today, technology and reliable equipment have enabled divers to extend their limits without all of the needed foundations. Massive dives beyond 100 m/328 ft, that until relatively recently were accessible to only the select few, are now “weekend” tech dives, often without surface support. I actually know people that do not dive shallower than 80m anymore because they cannot be bothered! Is this attitude followed by a parallel growth in knowledge and experience? Often not. And that is when we have a problem.

Many technical divers today would have a very bad day if they needed to do an ascent without a computer or even tables. Even though it is not a complicated thing to do, once you know what you are doing. Sometimes, the progress through certifications and into deeper diving is faster than the diver’s capacity to learn. We tend to forget that tools are there to only assist us, not do the job for us.. In the tech era we live in, we rely on electronics way too much. Computers don’t get bent, but divers may. The issue is not the fact that the computers aren’t doing what they are designed to do, it’s that divers can become dependent on them.

In my opinion, divers should progress slower, and most importantly take a different approach. During technical courses, divers are mostly taught gas management and gas switching skills. The fact that most agencies do not have their own (and that is a good thing) algorithms or deco procedure makes decompression a somewhat vaguer element in training. All the information about the effects of DCS is there; symptoms and dangers. But often the take away ends up being to “follow your software.” [Ed. Note that GUE teaches deco procedures that do not rely on dive computers]

I understand, given the uncertainty surrounding decompression, it can be difficult to define with certainty what to do, so courses tend to offer procedures that are “generally accepted as safe”. As a result, responsibility is transferred to the divers themselves. That’s why it’s imperative that divers become proficient in something that is so critical.

All technical divers are independent

Technical divers tend to be independent, it’s true. But some tend to follow, perhaps from habit, the advice of their recreational instructor who then becomes a permanent dive guide for them. That dependency isn’t in line with the level of knowledge and experience needed to do the dives they are certified for, so they depend upon the knowledge and experience from others and are not prepared to deviate from that.

Diving is an organic activity. It requires careful planning, granted, but not everything always goes as planned. Part of being a proficient technical diver is to be able to adapt and adjust to new situations and to adjust and respond without making mistakes. A diver who cannot do so, does not make for a good dive buddy. It would be a mistake to attempt serious dives with them.

One solution would be to treat advanced technical diving in incremental steps, applying the patience each step requires and anticipating the reward each step offers, which is considerable.

All technical divers are experienced

Technical divers, as well as recreational divers, often speed through their training, combining multiple courses without accumulating the necessary experience needed. The disadvantages to this approach are obvious, and not all of them have to do with safety. [Note: GUE requires divers to make 25 experience dives at the level of your course before taking the next level course.]

Let’s not forget we dive for fun. Why ignore all the shallow wrecks while racing to get your 100 m/328 ft certification quickly?? It’s true that many divers are less motivated, perhaps less excited, when they dive within their personal depth limits, in spite of the fact that each dive, with the right attitude, has its own unique thrill. If divers were more motivated to work their way slowly to depth and have fun doing it, they would be getting themselves more prepared for the next step.

Personally, every time I face a situation or a dive that feels new to me, due to the location, weather or other factors—not excluding dive buddies—I approach it with a combination of respect and excitement. Adding excitement to respect, helps me reduce fear. Removing respect from excitement increases risk.

Defining the ratio of these two elements is personal and paramount for each diver to truly grow. This process takes time to generate measurable awareness. It can’t be skipped or rushed. Divers should enjoy diving, monitor and celebrate each stage of growth, and challenge themselves in a gradual and measured way.

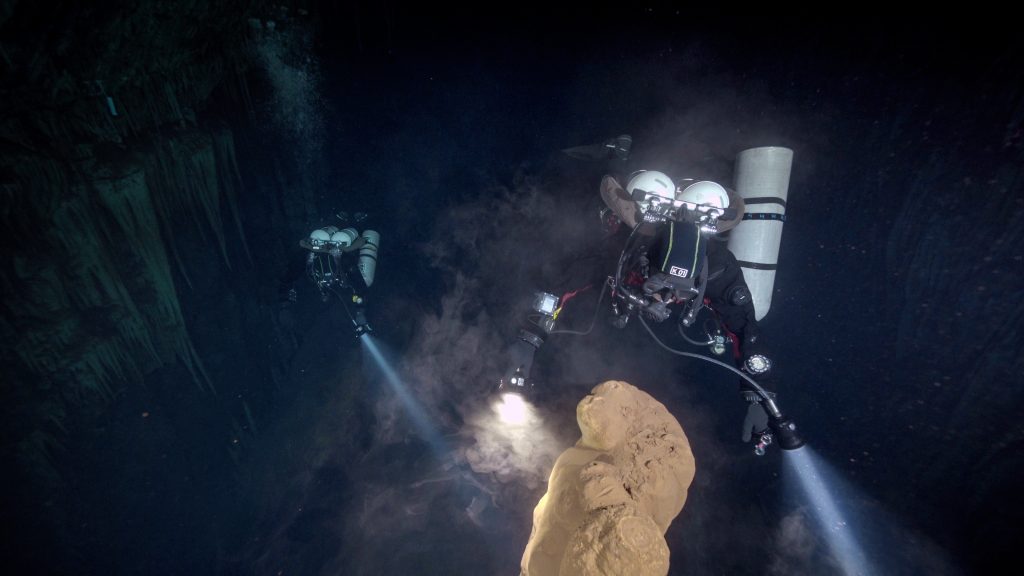

Only deep dives are worth it

Just don’t be that diver. Don’t be a depth snob. In more than two decades of diving, I am still amazed about the nonsense of the virtue of being deep for its own sake. Many compare it to driving fast. But it is not comparable, as speed is felt. The faster you drive, or fly, the more you feel the speed. Nowadays, diving deeper doesn’t really feel any different. Regulator technology (thankfully), and well designed rebreathers removed the perception of depth due to breathing resistance, and use of helium removes the narcosis. So a diver who is at 40 meters/130 ft will feel the same as a diver who is at 100 m/328 ft. Diving deep for a purpose—wrecks, recoveries, and teaching makes sense. Diving deep ‘just because’ doesn’t.

Let’s not endanger ourselves in order to have bragging rights. Deeper is not necessarily better. Enjoy shallow dives. Not just caves, but shallow reefs. There are some amazing shallow caves: Bel Torrente in Sardinia, Orda in Russia and one in Sinji in Greece. No deco, no trouble—just beauty. I’m not advising against deeper caves, just advocating not looking for them on purpose. For once the machismo is removed, shallow dives can be as rewarding, if not more so, than deep ones.

We can learn fundamentals as we go

All divers should take a “fundamentals” or foundations course. Actually all training agencies should include a (lighter) version directly during open water courses. First of all, there is no way to be independent as a diver without fundamental knowledge and skills. But as dive training is a business before anything else, at some point it went the other way and focused on minimum skills and time required to get a certification. As a result, some divers ended up learning their fundies as you go. Well, that may be ok (not really) during recreational diving, but it’s downright dangerous in the technical path.

It’s normal that advanced open water divers want to learn tech and cave diving. These days, with all the press and information available, the awareness about technical and cave diving has increased, seemingly making it more accessible to everyone.

As a result, too often divers with barely sufficient skills and experience want to enroll in demanding courses like the above mentioned. When asked to prove that they have the basic or fundamental skills needed to enroll, they explain that it’s the reason they want to do the course; to improve their fundamental skills. Following the lead of Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) and its Fundamentals course, over the last decade, most agencies have introduced a fundamentals type course. But still, many students expect to incorporate that training in an already time-constrained course like an intro to cave or a trimix course.

Divers who want to improve skills, should find a fundamentals course that will do that.

Scuba diving is a (competitive) sport

Among other things, the definition of a “sport” explains that there is a measurable performance that differentiates winner(s) from loser(s) that is, the one who runs faster wins. In scuba diving this is a very dangerous notion, as it pushes divers to compete against one another , often pushing their limits beyond their comfort zone. [Ed. Note that free diving does have a competitive component to it with an demonstrated safety record.]

Scuba diving is not a sport. It’s an activity. Much like hiking is about seeing wonderful new places, recording mental (or real) images and returning home with a new appreciation of nature, and alive. Actually, scuba diving is just that: underwater hiking. No need to add unnecessary risk by pushing limits that don’t offer any additional value to the actual dive.

Checklists are only for rebreathers

Once it was the fins. Another time it was the drysuit. Many times it was the mask, then the backup mask. On occasion it was the backup lights. Closed valve. Computer and bottom timer. Multiple times. Compass? Do I own one?

It’s very complicated to be certain that everything works perfectly during scuba diving. The extensive equipment, procedures, and unknown and uncontrollable parameters create room for constant alterations from the ideal plan.

The solution is using checklist(s). They are used constantly by professionals, in situations where the sheer amount of information, tools and procedures risk overwhelming the user, no matter how skilled. Using a checklist guarantees a constant, relaxed performance and reduces the chance that something will be skipped or forgotten. Checklists have become standard protocol for rebreather divers, but their benefits apply to open circuit divers as well.

Checklists save projects, fun dives, and lives. There should be one for what you need to leave home with: charge lights and scooters; check batteries on the backup lights, check BCD integrity. Anything that cannot be fixed or replaced easily on the day of the dive. A separate dive center checklist is a good idea–one that includes gas analysis. And finally, a pre-dive checklist.

Stratis Kas is a diving instructor & explorer, a film-maker, adventurer and storyteller. Stratis Kas deals with all of his subjects — extreme weather expeditions to days lost in wilderness — with unique sensitivity and fearless focus. He travels to remote, sometimes risky, and often freezing locations to create stunning films that change what we know about diving expeditions.

Since 2016, he has led the Top2bottom cave filming team that specialize in Adventure Filming. In 2017, he finished his first film “Amphitrite” that won a finalist place in the film festival, “Short to the Point” in 2018. Currently he is finishing his second feature film “Infinite Liquid” produced by Because I Can Ltd.