Community

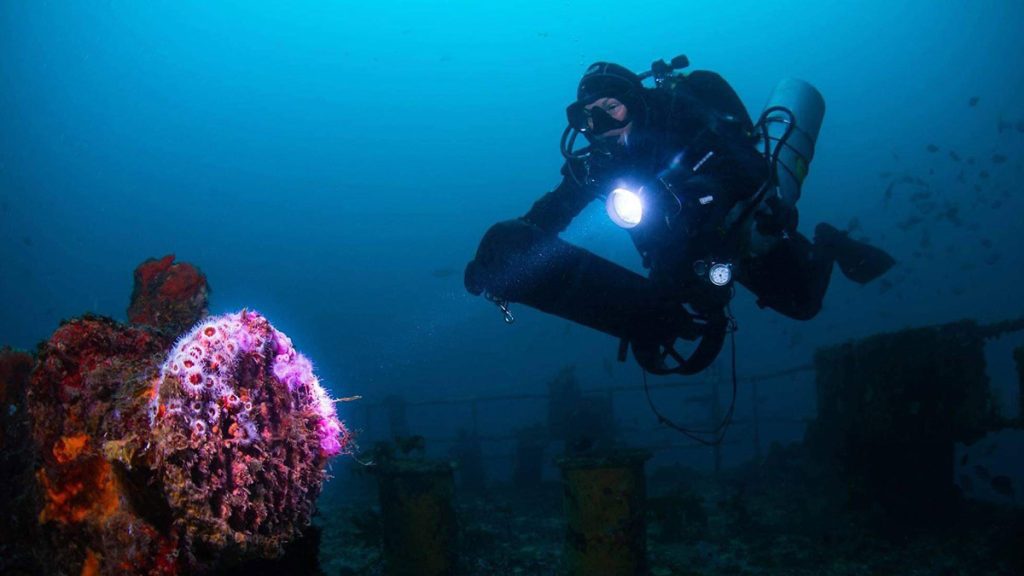

Open Circuit Technical Diving Is Not Dead

by Richard Taylor. Images courtesy of Rob Wilson unless noted.

Hindsight can be sobering. Eight years ago, I argued open circuit (OC) technical training was becoming obsolete because of the push toward closed circuit rebreathers. Turns out, I was a bit aspirational, and wrong. We’re still not there—not even close. And maybe we will never be.

A version of the piece, “Is There Still A Case for Open Circuit in Tech,” was first published in X-Ray Mag #70 in 2015, back when the question—Is Open Circuit Technical Diving Dead?— was about whether the push toward rebreathers would mean the end of OC training. Now, with rebreathers (CCRs) seemingly even more ubiquitous in technical diving, the question about whether there’s a place for open circuit at all is even more pertinent.

Ask a CCR diver (a passionate bunch, to say the least) and they’ll likely dismiss the need for open circuit technical training. Many divers are swayed by the potential deep dive cost benefits, often brought on from CCR divers highlighting gas costs, longer bottom times and shorter deco. But most CCRs are not yet at the stage of CCR redundancy, and OC skills remain the primary backup for these divers.

Some experienced CCR divers are arguing against the need for such training, even though they have likely had extensive OC training themselves, on which they will be able to lean if their rebreather fails and they have to bail out. Simply put, these experienced divers are asking new divers to take a risk they don’t have to take themselves.

As such, open circuit still has an important place in technical diving. Not only is OC technical diving alive and thriving in some areas, but we need to consider that OC technical training should be mandatory for all technical divers, even those diving on CCR.

Where are We Heading?

Eight years ago, I wrote the following in a previous version of this article (edited for clarity):

“Excluding global disaster, you have to say that the CCRs are here to stay, and will only become more entrenched. More CCR manufacturers will enter the market with a resultant drop in prices as competition increases. The move to “Recreational” CCRs will increase as both established and new CCR manufacturers see this as a profitable share of the market, resulting in more retailers investing in this area to increase their own sales.

As the recreational CCR market builds and unit price drops more divers will move along the CCR pathway. Divers will be drawn to CCR Training sooner and CCR Programs will become less reliant on any OC prerequisite.

Of course, the rate at which this will occur will depend upon many forces, some internal in diving, some external. However, one thing is certain, CCRs are probably not going to go away.”

In eight years, not much has changed—except that the CCR lobby has grown even louder. As we continue to see a greater focus from the industry on CCR, we are seeing a need for easier unit crossovers, and potentially even a need for basic unit standardisation. But, along with this, we are also seeing a decline in OC skills for CCR divers.

CCR hype has reached a crescendo. New CCR models are being introduced regularly (25+ mainstream agency recognised units at last count) with multiple tech units, “Type R” (recreational) and semi-closed and closed circuit variants for specific needs. We now have a European Rebreather Standard (EN14143) and RESA, the Rebreather Equipment & Safety Association.

Alongside this, the training agencies have pursued CCR divers with their usual commercial vigour, and there is a well-worn pathway allowing divers to develop along the technical side on CCR, often with little, if any, requirement for OC tech qualifications. Today’s aspiring technical diver Can be CCR trained with nothing more than four open circuit dives as an open water scuba diver.

CCR Training Alone Is Not Sufficient

In looking at current programs, CCR training courses need to include a stronger focus on core OC options such as OC gas consumption rates and dive planning. OC technical skills should be regarded as a mainstay of CCR diving as pretty much every CCR course still teaches bailout to open circuit.

Many CCR divers, sadly, often portray OC tech diving as obsolete, like needing to learn how to drive a manual stick shift when you get your driver’s license. In other words, just learn in an automatic. They say that if you dive CCR, you learn how to plan an OC bailout, and that it makes more economic sense to just go CCR from the beginning.

But keep in mind, virtually all of the divers making that argument still have OC training to fall back on in an emergency but it remains to be seen how the lack of that training will affect up-and-coming CCR divers. After all, how many CCR divers actually have a bailout CCR?

OC Tech Training Remains Relevant

If we look at most current CCR training courses, there appears to be a need to include a stronger focus on core OC options such as OC gas consumption rates and dive planning. OC technical skills should be regarded as a mainstay of CCR diving as pretty much every CCR course still teaches bailout to open circuit.

Let’s not forget the size of the OC and OC technical market. Significant, upfront investment, access to training, rebreather support and services are critical to becoming a successful CCR diver. I don’t know if anyone has done a study on the untapped or latent technical diving market size, but I can use SDI/TDI President of International Training Brian Carney’s 2016 DEMA presentation on “How Big is the Technical Diving Market?” His data indicated that the ratio of OC tech vs. CCR tech was roughly 6:1. There are six OC tech divers to every CCR diver!

We must also recognize the inherent privilege embedded in the question about whether OC tech diving is dead. Diving isn’t a cheap sport by any means, but most divers don’t have the luxury of being able to buy a rebreather and support its ongoing costs and maintenance. CCRs might over time lessen the costs of tech diving, but not before a diver forks over what amounts to a year of college tuition for the unit and training. So maybe the CCR divers who are calling for the end of OC tech need to consider their own CCR privilege.

In time, CCRs may well dominate resorts, boats, and diving operations around the world, and there may emerge another bailout option for CCR divers i.e., rebreather bailout.

But until that time comes, OC will be the “go to” option, and if we allow our CCR divers to progress through tech without sufficient OC skills, we are not only doing them an injustice but ourselves. There are currently about 20 CCR Fatalities each year (pre COVID). It is when things go wrong that we often say to ourselves, “If only I’d done or said that.”

We began the discussion on OC vs CCR here (June):

Will Open Circuit Tech Diving Go the Way of the Dinosaurs? By Neal Pollock

GUE and the Future of Open Circuit Tech Diving By Ashley Stewart

Is deep, open circuit tech diving destined to share the fate of the spinosaurus? Complete our short survey: OC v CCR to find out.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

X-Ray Mag: Is There Still A Case for Open Circuit in Tech by Richard Taylor (2015)

DIVER mag: Rise of the Recreational Rebreather by Michael Menduno (2014)

TDI Blog: How Big is the Technical Diving Market? by Brian Carney

Technical Diving Instructor Trainer, Co-founder of TDI & SDI in Australia & NZ, and OZTeK Founder Richard Taylor may not be a diving dinosaur, but he has been around long enough to remember some of them!

Richard has over 30 years’ experience in technical diving (25 as an IT) including some of the first trimix dives in Australia in 1994 (before certifications were available). He was Regional Director for TDI/SDI Australia/NZ for over 15 years and founded or was part of many early technical diving projects in the region. He also founded & ran the acclaimed OZTeK Conferences from 1999 to 2007.

Richard has taught hundreds of technical divers and Instructors around the world and continues to teach today for SDI/TDI/FRTI and is one of the few Instructor Trainer Evaluators.

He is not afraid of voicing a strong view on subjects and, as a past rebreather diver & instructor, is a passionate advocate for training and maintaining open circuit technical diving skills. His strong belief is that as we gain more experience we gain a responsibility to pass our knowledge and skills on to others so that those who come after us can go further than we have, and come back and tell us their story!