Latest Features

Playing with Fire: Hydrogen as a Diving Gas

As every tekkie knows, helium is essential for deep diving due to the fact it’s non-narcotic and offers low breathing gas density. But it’s conceivable that hydrogen may one day become a part of the tech tool kit for dives beyond 200 m/653 ft, by virtue of the fact that it’s light, a little narcotic and offers the possibility of biochemical decompression. Diver Alert Network’s Reilly Fogarty has the deets.

by Reilly Fogarty

Header photo courtesy of DAN.

The pool of people who explore the ocean depths beyond 122 m/400 ft is small, and the group of people who do it regularly and need to reach those depths quickly is microscopic. This niche application coupled with a significant fire hazard make it easy to understand why exotic gases like hydrogen have escaped both common use and public interest.

Despite the obvious concerns, however, hydrogen has shown some capacity to ameliorate the effects of high pressure nervous syndrome (HPNS) in deep divers, improve function at extreme depth, reduce work of breathing, and present a possible alternative to helium in case of helium reserve depletion. Use of the gas has made it possible to dive deeper, get to depth faster, and stay there longer, but there is a substantial risk-versus-reward calculation to be made before considering its use. Interested in diving deep and dabbling in the cutting edge of diving research? Here’s what we know about using hydrogen as a diving gas.

High Pressure Nervous Syndrome

Records of sojourns into the use of hydrogen as a breathing gas go back to as early as the 18th century with the experiments of Antione Lavoisier, but the use of the gas came to a head during the heyday of deep diving research in the late 20th century. From the Atlantis dives at Duke University to the Hydra Missions and the evolution of the Compagnie Maritime d’Expertises (COMEX) tables, researchers and deep divers quickly found issues as they pushed to explore deeper depths. Racing past 184 m/600 ft, researchers discovered that divers would face several new and potentially deadly phenomena in their push to the bottom. Chief among these was a condition that came to be called high pressure nervous syndrome. The condition was first described as “helium tremors” by Russian researcher G. L. Zal’tsman in 1961 and Peter B. Bennett in 1965 (Zal’tsman’s research was not available outside of the Soviet Union until 1967).

Comex and Club des Anciens de Comex sites : www.comex.fr and www.anciencomex.com

Later this condition would be named and correlated with symptoms including tremors, headache, dizziness, fatigue, myoclonic jerking, muscular weakness, and euphoria. Gastrointestinal complaints, memory and cognitive deficits, psychomotor impairment, nightmares, and somnolence are also possible, and convulsions have been noted in animal models (Kangal, 2019). The mechanism of HPNS has not yet been proven, but there are several working theories.

The first of these involves the compression of lipid components of the cell membranes in the central nervous system (CNS). Some theorize that the compression of these tissues may affect the transmembrane proteins, ion channels, and surface receptors critical to the signaling pathways of the CNS (Talpalar, 2007). Many connect the use of hydrogen to mitigate the effects of HPNS to this model. Some research has shown that anesthetic gases can reduce the effects of HPNS, and this has been proposed to be driven by some pressure reversal effect of narcosis (Kot, 2012). Hydrogen is a narcotic gas, and this may be one component of its ability to reduce the onset or severity of HPNS. This mechanism, the compression of lipid components also appears to be the one that initially gave rise to the use of breathing gases as a way to ameliorate the effects of HPNS, with some groundwork for this foundation laid out by Peter B. Bennett, PhD, as early as 1989 (Bennett, 1989).

Other researchers have focused on neurotransmitters, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and others. These models have also shown promise, one study showing a GABA increase in the cortex diminishing HPNS signs in baboon models and another showing NMDA antagonists preventing convulsions in rats (Pearce, 1989, 1991). Similar studies have been conducted with a range of neurotransmitters and neuronal calcium ion channels with similar results. In short, there are several potential avenues for the specific mechanism of HPNS, and while the general mechanism is likely a combination of several models, none have yet been definitively proven.

What we know is that there is notable variation in HPNS onset among divers (Bennett, 1989), and onset appears to be the result of a combination of breathing gas, compression rate, and depth. Faster compression, lower nitrogen, or hydrogen content in helium/oxygen breathing gases, and deeper depths have been correlated with more rapid onset and more severe symptoms (Jain, 1994).

The Benefits of Hydrogen

The use of hydrogen as a diving gas doesn’t just stem from its ability to reduce the onset of HPNS—it’s an extraordinarily light gas that’s useful in reducing work of breathing at extreme depth and a potential replacement for helium when worldwide demand has led to a quickly dwindling reserve. One U.S. Navy paper went so far as to propose hydrogen replacement of helium due to helium scarcity leading to a predicted depletion of supply by the year 2000 (Dougherty, 1965). Thankfully, that mark has come and gone due to the discovery of several new helium sources, but it’s not an unrealistic concern when the demand for helium is so high in manufacturing, aerospace, and technology.

Comex and Club des Anciens de Comex sites : www.comex.fr and www.anciencomex.com

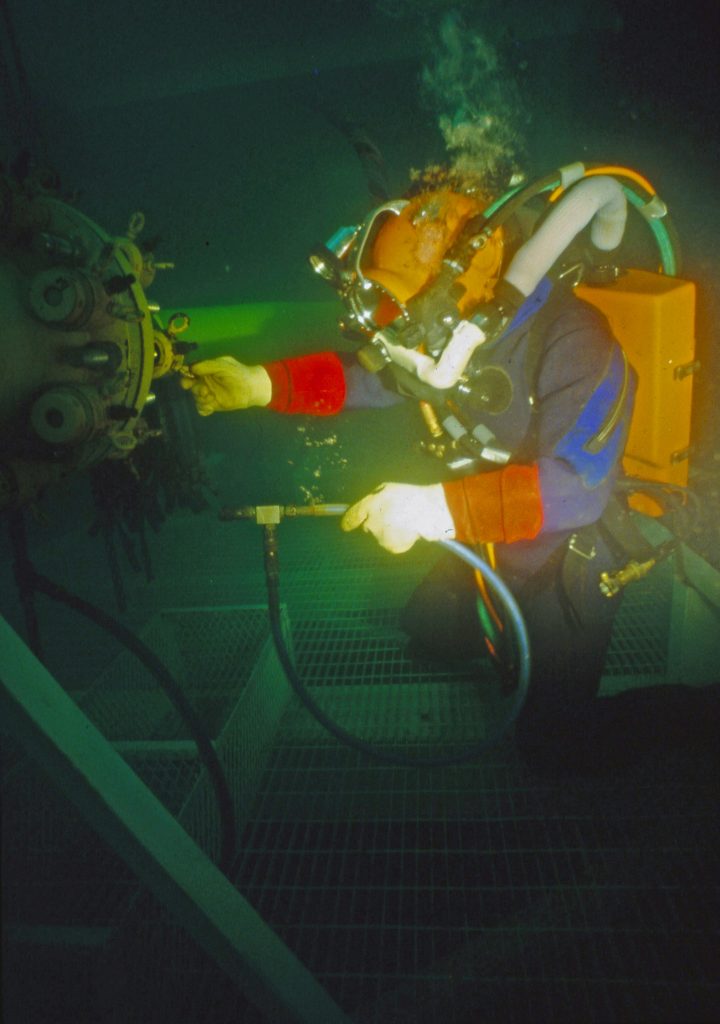

The benefits of hydrogen are notable, but the hazards are nothing to balk at. Little research has been done on the decompression or thermal properties of hydrogen in divers, it’s reported to be mildly narcotic, and it’s highly flammable. While oxygen is an oxidizer that can feed a fire, hydrogen is actively flammable—in the presence of sufficient oxygen and a source of ignition, it will combust in dramatic fashion. In practice, this combustibility is managed by reducing both the sources of ignition and the available oxygen. With the lower explosive limit of hydrogen being around 4% by volume, using less than this amount in normoxic environments effectively mitigates the fire risk but does little for deep divers. Instead, extremely hypoxic gases and high concentrations of hydrogen and helium have been used with great success. The COMEX Hydra VIII mission, for example, used a mixture of 49% hydrogen, 50.2% helium, and 0.8% oxygen to take divers to a maximum depth of 536 m/1,752 ft.

The decompression profiles used in these deep saturation dives appear to be effective as well. As early as 1992, COMEX researchers found that teams of divers on a hydrogen mixture at a depth of 210 m/686 ft performed tasks more efficiently, both cognitively and physically, than their counterparts on helium (Offshore-mag.com, 1996). The same experiment resulted in a bubble study that showed “no evidence of bubbles” in the divers following decompression—an exercise in small sample sizes perhaps, but with promising results. (Note: Researchers suspected that “biochemical decompression” might be involved, i.e., a process in which metabolism of H2 by intestinal microbes facilitates decompression—ed.) U.S. Navy research found similar results, indicating that hydrogen increased the capacity for physical effort as a result of a decrease in work of breathing at depth (Dougherty, 1965).

Functionally, the benefits of the gas are hard to dispute; work of breathing is a constantly growing area of concern for dives at all depths, HPNS is a constant concern, and minimizing decompression is a perpetual goal. For divers reaching extreme depths without the ability to perform saturation dives, diving to depths beyond 122m/400 ft is a repetitive gamble with no guarantee of success. Rapid compression combined with limited options for gas mixes result in the need to play a dive profile by “feel” with emergency plans in place to respond to HPNS onset, and more than one diver, likely including Sheck Exley (See: “Examining Early Technical Diving Deaths,” by Michael Menduno, InDepth 2.2) has lost their life to the condition.

The Hazards of Hydrogen

By the same token, hydrogen presents unique hazards that require careful consideration. Unexplored decompression profiles and limited research on long-term effects make the decision to dive with hydrogen difficult, and the significant risk of fire places divers in more danger than is typically acceptable. Add to this the limited applications (either hydrogen content below 4% in normoxic environments or oxygen content below 6% in high-hydrogen environments), and it quickly becomes apparent why hydrogen hasn’t yet hit the mainstream.

The presence of project divers in our community performing near saturation dives with trimix and makeshift in-water habitats skews favor away from hydrogen as well, making it a gas viable only for the deepest dives without the option for saturation. The case for hydrogen isn’t entirely up in smoke, however. Research showing significant decompression benefits or depletion of helium reserves may well push us toward helium’s more flammable cousin, but it’s unlikely you’ll see hydrogen at your favorite fill station any time soon.

References

- Ozgok Kangal, M.K., & Murphy-Lavoie, H.M., (2019, November 14). Diving, High Pressure Nervous Syndrome. (. In: StatPearls StatPearls Publishing.

- Talpalar, A.E., (2007, Nov 16-30). High pressure neurological syndrome. Rev Neurol., 45(10), 631-6.

- Kot, J., (2012). Extremely deep recreational dives: the risk for carbon dioxide (CO2) retention and high pressure neurological syndrome (HPNS). Int Marit Health, 63(1), 49-55.

- Bennett, P.B., (1989). Physiological limitations to underwater exploration and work. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol., 93(1), 295-300.

- Pearce, P.C., Clarke, D., Doré, C.J., Halsey, M.J., Luff, N.P., & Maclean, C.J., (1989. March). Sodium valproate interactions with the HPNS: EEG and behavioral observations. Undersea Biomed Res. 16(2), 99-113.

- Pearce, P.C., Halsey, M.J., MacLean, C.J., Ward, E.M., Webster, M.T., Luff, N.P., Pearson, J., Charlett, A., & Meldrum, B.S., (1991, July). The effects of the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist CPP on the high pressure neurological syndrome in a primate model. Neuropharmacology,30(7), 787-96.

- Jain, K.K. (1994, July). High-pressure neurological syndrome (HPNS). Acta Neurol. Scand.,90(1), 45-50.

- Dougherty, J., (1965). The Use of Hydrogen As An Inert Gas During Diving: Pulmonary Function During Hydrogen-Oxygen Breathing At Pressures Equivalent to 200 Feet of Sea Water.

- Saturation diving tests support claims for hydrogen breathing mix, (1996). Offshore-mag.com.

Dive Deeper

InDEPTH: Hydrogen, At Last? (2023) by Michael Menduno

InDEPTH: N=1: The Inside Story of the First-Ever Hydrogen CCR Dive (2023) by Ashley Stewart

InDEPTH: The Case for Biochemical Decompression by Susan R. Kayar

John Clarke, retired scientific director of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit, is knowledgeable about hydrogen diving and has used that knowledge both in his blogs as well as in the undersea sci-fi thrillers, the Jason Parker Trilogy , of which he is the author.

Diving with Hydrogen – It’s a Gas

Hydrogen Diving – A Very Good Year for Fiction

The deepest saturation dive (using hydrogen) to 534 m/1,752 ft conducted by COMEX

Biochemical Decompression:

Fahlman, A., Lin, W.C., Whitman, W.B., & Kayar, S.R., (2002, November). Modulation of decompression sickness risk in pigs with caffeine during H2 biochemical decompression. JApp. Physio. 93(5).

Kayar, S.R., & Fahlman, A. (2001). Decompression sickness risk reduced by native intestinal flora in pigs after H2 dives. Undersea Hyperb Med., 28(2), 89-97.

Fahlman, A., Tikuisis, P., Himm, J.F., Weathersby, P.K., & Kayar, S,R., (2001, December). On the likelihood of decompression sickness during H2 biochemical decompression in pigs. J Appl Physiol., 91(6), 2720-9.

Reilly Fogarty is a team leader for risk mitigation initiatives at Divers Alert Network (DAN). When not working on safety programs for DAN, he can be found running technical charters and teaching rebreather diving in Gloucester, Mass. Reilly is a USCG licensed captain whose professional background includes surgical and wilderness emergency medicine as well as dive shop management.