Community

Risk-Takers, Thrill-Seekers, Sensation-Seekers, and … You?

It’s likely that many in our community no longer think of tech diving as a risky activity, or perhaps even appreciate how important taking risks may be to one’s personal health—let alone that of our species. Fortunately, InDEPTH’s copy editing manager Pat Jablonski dived deep into the origins, meaning, and benefits of regularly taking risks, and even offers a thrill-seeking quiz for your edgy edification. What have you got to lose?

by Pat Jablonski. Title photo courtesy of Katelyn Compton Escott.

“Life without risk is not worth living.” – Charles Lindbergh

What defines a risk? What is involved in taking a risk?

Difficult questions to answer, because something that feels risky to one person might be yawn-worthy to another. Risk taking, unscientifically, is something you do that gets your blood up, raises your heartbeat, awakens your senses, and makes you hyper-aware of your surroundings.

Surely we can agree that the Covid pandemic has added an unexpected level of risk to everyday life. Add poor drivers, mass shootings, contentious politics, global climate change, and many are left believing that meeting each day is risky enough. But that’s not true for people who identify as risk-takers or thrill-seekers.

“Everyone has a ‘risk muscle’. You keep in shape by trying new things. If you don’t, it atrophies. Make a point of using it once a day.” – Roger Von Tech

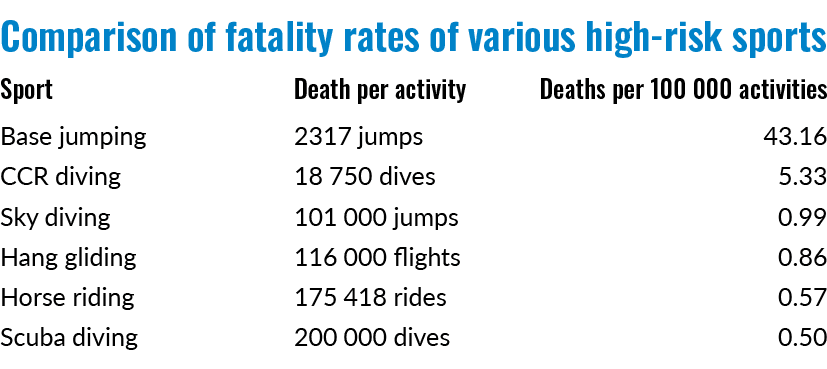

There are many activities that go to the trouble of defining the level of risk involved with a specific activity, and while that’s not the purpose of this article, you should know that scuba diving ranks fairly high on the risky behavior scale–higher than skydiving and rappelling. And, cave/wreck diving or freediving isn’t on any risk scale we could locate. We can assume it’s up there—near or at the top.

Divers are a fairly small niche group for many reasons. One of them could involve the degree of danger associated with the sport. Answer this: Do dry land people ever ask you why you would want to take such a chance with your life in order to go where you weren’t meant to go?

It’s a reasonable question, albeit a hard one to answer.

“A life without risk is a life unlived, my friend.” – Big Time Rush

Kevin Costner’s Waterworld aside, humans have (yet) to be born with gills or webbed toes. Still, there you are. You’ve spent unmentionable amounts of money. You’ve carved out a whole day, or maybe weeks, away from your to-do list. You’re suited up and look like an alien. You’re on a quest to explore the aquatic world where you’re able to breathe only with a cumbersome apparatus. You’re planning to explore inner space! You’re going to delve into that amazing realm that’s off limits to most people.

You may look all matter-of-fact, cool as a cucumber, another day at the office, but it’s a thrill, isn’t it? Inside, you’re a kid with butterflies in your tummy who’s getting away with something big and exciting. Okay, it’s true–you and your team are highly trained, your equipment is top-notch, every box is checked off, and you are behaving responsibly. However, you’d have to be in a coma to not realize that what you’re about to do is taking a risk. Who doesn’t know that people have died doing what you’re doing? Answer honestly: How much more exhilarating is the experience when you know it’s not a walk in the park? Our own Michael Menduno admitted that “the feeling of being more alive lasted for days” after a dive.

So, you’re a diver. Does that mean you’re a risk taker? A thrill seeker? A sensation seeker?

Let’s dive into that subject, first by taking a little quiz, shall we?

From A Death Wish to Life Is Precious

In the past, too many mental health professionals treated risky behavior like a disease in need of a cure, focusing on the negative side of risk, even using government funding to address risky behavior and stamp it out.

Before that, Sigmund Freud might have even believed that thrill seekers had a death wish; in fact, it’s what was believed for many years.

Modern-day science doesn’t support either theory.

“Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” – TS Elliot

For our purposes, we’re focusing on the positive aspects of taking chances, pushing boundaries, and seeking experiences that make life feel . . . more alive. Richer. Fuller. We want to examine what goes into the psyche of a person (like you?) who is enthusiastically willing to engage in an activity already identified as dangerous, possibly even by the people who are engaging in it, and hear what some experts on the subject have to say about such people.

The University of Michigan’s Daniel Kruger proposes that taking chances is a fundamental part of human nature going all the way back to our ancient ancestors—prehistoric humans who had to constantly put their safety on the line in their fight for survival. Think fighting off a wooly mammoth with a stick. Kruger believes we have consequently retained many of those same instincts today, and he believes that it’s a good thing.

This writer, who is related to a major risk-taker, has always believed that heart-quickening experiences are essential for a well-lived life. I’m convinced and have long proposed that those pulse-pounding moments are often accompanied by a deepened understanding of and appreciation for one’s life—perhaps all life. And I’m happy to report that current science confirms that belief.

“If you are not willing to risk the unusual, you will have to settle for the ordinary.” – Jim Rohn

Dr. Kruger is one of the scientists who proposes that taking risks means “seeking that moment when life feels most precious.”

This should not be news for you diving adventurers out there.

Nature vs. Nurture: Born That Way or Learned To Love Adventure

Another scientist, Marvin Zuckerberg, affirms the theory that risk taking is in our DNA. “Certain people have high sensation-seeking personalities that demand challenges and seek out environments that most people’s brains are geared to avoid.” I’ll go out on a limb and say that underwater caves or shipwrecks would qualify as environments most would avoid.

Dr. Cynthia Thompson, the researcher behind a 2014 study from the University of British Columbia, was early to look at the genetic factors that might make a person predisposed to participating in extreme sports, ones that are typically defined as activities where death is a real possibility. The results of her study revealed that risk-takers shared a similar genetic constitution, a genetic variant that influences how powerful feelings are during intense situations.

Most scientists agree that personality is a complicated mix of genetic and environmental influences. The “nature vs. nurture” dilemma is alive and well. Dr. Thompson concluded that people who engaged in so-called high-risk sports were not impulsive at all, not reckless either. Instead, “they’re highly skilled masters of their discipline who take a very thoughtful approach to their sports.”

A study conducted in 2019 examined human boundaries, people who pushed them to their limits and beyond, and what made those people tick. Zuckerman labeled such people “sensation seekers” and defined them as “people who chase novel, complex, and intense sensations, who love experience for its own sake, and who may take risks to pursue those experiences.” Is that you?

“History is full of risk-takers. In fact, you could say that risk-takers are the ones who get to make history.” – Daniel Kruger

Other experts posit an alternate theory—one proposing that modern society in the age of seatbelts, guardrails, child-proof caps, safety precautions, laws, rules, and regulations has dulled the sense of survival. In other words, life has flattened out and no longer feels exciting, or risky. So, is one of the reasons we seek excitement because of boredom?

Maslow’s Theory of Self-actualization

I don’t honestly know who was the first proponent of risk-taking being a positive thing, but the work of Abraham Maslow, the founder of humanistic psychology, was one of the first. Maslow became one of the most influential psychologists of the twentieth century, and he developed a theory of human motivation that advocates for “peak experiences.” Peak experiences are not attained without risk.

“One can choose to go back toward safety or forward toward growth. Growth must be chosen again and again; fear must be overcome again and again” – A Maslow

He proposed that, in addition to meeting basic needs, all humans from birth seek fulfillment in terms of what he called self-actualization—finding their purpose/being authentic. Self-actualization involves peak experiences—those life-altering moments that take us outside ourselves, make us feel one with nature, and allow us to experience a sense of wonder and awe. Maslow also believed that those who were able to have such peak experiences tended to seek them out rather than waiting for the next random occurrence. Hence the anticipation of the next dive?

“Do one thing every day that scares you.” – Anonymous

Out of Your Comfort Zone Into A World of Wonder

Psychologist Eric Brymer from Queenstown University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, has spent years studying extreme athletes and has this to say: “They’re actually extremely well-prepared, careful, intelligent, and thoughtful athletes with high levels of self-awareness and a deep knowledge of the environment and of the activity.”

Recent research backs up what some extreme sports athletes have been saying for years, even if only to themselves.

“What participants get from extreme sports is deeply transformational, a sense of connecting with a deep sense of self and being authentic, a powerful relationship with the natural world, a sense of freedom,” says Brymer. “They get a strong sense of living life to its fullest as if touching their full potential.”

Brymer’s comments mirror what Maslow, the founder of humanistic psychology, said back in the 1940s.

We’re not advocating for taking stupid chances (such as diving without proper training, or necessary precautions) and we don’t believe anyone reading this article does that. We simply intended to focus on the scientific evidence that supports adventurers—people who get a thrill from an activity that offers—as a bonus; a chance to feel awakened from the mundane and thrust into a world of wonder.

Risk-takers and sensation- or thrill-seekers chase unique experiences. Often, those experiences bring awareness of important issues or increase essential knowledge about the planet we share. Many people overanalyze and dither when faced with an unfamiliar situation; they shy away from unsettling circumstances. Risk-takers face the unknown and trust themselves to prevail. Learning to scuba dive, for example, pushes people out of their comfort zone, takes them into a realm foreign and mysterious. Diving forces divers to pay complete attention to a task, to focus with laser-like precision in order to conquer misgivings, and to attain a skill that few others have. Confidence comes with accomplishment. Leadership emerges. Fear is overcome.

Sensation-seekers see potential stressors as challenges to be met rather than threats that might defeat them. With action, resilience develops. High sensation-seekers report lower perceived stress, more positive emotions, and greater life satisfaction. Engaging in extreme activities brings them peace.

What does it bring you?

Dive Deeper

Bandolier: Risk of dying and sporting activities

National Geographic: What Makes Risk Takers Tempt Fate? Recent research suggests that genetic, environmental, and personal factors can make people take on risky—even potentially fatal—challenges.

Healthday: Taking Risks By Chris Woolston HealthDay Reporter

Pat Jablonski heads up the copy edit team for InDEPTH. She is a blogger, a writer of stories, a retired tutor, English writing teacher, and therapist. She’s a friend, a wife, a proud mother and grandmother. She is also a native of Florida, having spent most of her life in Palm Beach County. She has a B.A. in English from FAU in Boca Raton and an M.S.W. from Barry University in Miami. She learned to swim in the ocean, a place she thinks of as home, but she doesn’t dive.